6 Indigestion (chronic epigastric pain or meal-related discomfort)

Case

A 39-year-old female psychologist consults because of problems with indigestion for the past year. She states that after eating a meal she feels very uncomfortable and full. The discomfort she experiences is not at the level of pain, but does interfere with her life. She also feels bloated and is unable to finish normal-sized meals now. She has these symptoms after most meals. She very occasionally will have heartburn (retrosternal burning discomfort in her chest travelling up towards the throat). She never has acid regurgitation and denies dysphagia. She is slightly nauseous at times, but denies vomiting. She has not noticed any change in her bowel habit. Her weight has fluctuated up and down, but overall has been stable. She remembers her mother suffered for years with indigestion problems. She is not taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs supplied ‘over the counter’.

Indigestion and Dyspepsia

The terms ‘indigestion’ and ‘dyspepsia’ mean different things to different people. It is therefore important to clarify with a patient what they mean by indigestion. The term is generally used by patients to describe symptoms related to the upper abdomen or chest. ‘Dyspepsia’ is a term usually used only by medical practitioners, and refers to one or more of the following symptoms: chronic or recurrent epigastric pain, epigastric burning, postprandial fullness or early satiation (inability to finish a normal-sized meal). However, many also include classical symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux (namely heartburn or acid regurgitation) as part of dyspepsia, which has caused confusion; others also include nausea or belching although these symptoms probably have a different pathophysiology (see Ch 1 and Ch 9). The most important underlying causes of dyspepsia are peptic ulcer disease (uncommon), gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (common), cancer (rare) and functional dyspepsia (most common).

Mechanisms Underlying Epigastric Pain

A diverse range of physiological or pathological mechanisms can result in chronic or recurrent epigastric pain. These include (1) inflammation, not only acute, but also chronic; (2) abnormal motor activity producing distension or excessive contraction of hollow organs; (3) hypersensitivity of hollow viscera in the upper gastrointestinal tract; (4) stretching of the capsules of solid viscera, for example the liver; (5) malignant invasion of nerves; and (6) organ-specific responses, such as acid and pepsin acting on nerve fibres in the base of a peptic ulcer. Based on the afferent relays or pathways for pain impulses, activated by these processes, three different types of pain can be appreciated clinically. These types can occur in isolation or together in the one individual. Visceral pain arises from nociceptors situated in the walls of the abdominal viscera, somatic pain from nociceptors situated in the parietal peritoneum and supporting tissues, and referred pain by activation of strong visceral impulses spilling over to the somatic afferent neurones in the same spinal cord segment (Ch 4). Visceral pain tends to be dull, perceived in the midline and poorly localised; it may be described in terms other than ‘pain’, and may be accompanied by symptoms of autonomic disturbance. Somatic pain, like referred pain, tends to be sharp or aching, sustained, lateralised and yet relatively poorly localised; it may be worse on movement. Referred pain tends to be sharp or aching in character, lateral or bilateral and roughly localised to the somatic dermatome. When patients describe pain as superficial, it may arise from lesions in the abdominal wall or hernial sac, but may occasionally also represent referred pain, from disease in intraabdominal or thoracic viscera.

Clinical Assessment

Epigastric pain, which is considered to represent a sense of tissue damage, should be distinguished from discomfort; the latter refers to a subjective, negative feeling that does not reach the qualification or intensity level of pain. Discomfort can include a number of other symptoms including early satiation (inability to finish a normal-sized meal), postprandial fullness and nausea (Ch 9). It is useful to determine the major complaint: whether the symptoms are related to meal ingestion or not, and whether they are intermittent (recurrent or cyclical) or continuous. As with any symptom, the other specific features need to be ascertained, including the site, mode of onset, intensity, character, and precipitating and relieving factors (see Ch 7). For the purposes of this discussion, a duration of 3 months or longer is taken as indicating chronicity, which distinguishes dyspepsia from the acute symptoms present in disorders such as perforated peptic ulcer, acute cholecystitis and acute pancreatitis (Ch 4).

Overlap of dyspepsia with other syndromes

Symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and dyspepsia often overlap. Because of the high specificity of the symptoms of GORD, however, if the patient has predominant or frequent symptoms of heartburn or acid regurgitation, as well as upper abdominal pain/discomfort, the condition should usually be classified as symptomatic GORD, irrespective of the presence or absence of endoscopic oesophagitis (see Ch 1). Likewise, while retrosternal chest pain, and even dysphagia, may be regarded by the patient as indigestion, they should not be classified as dyspepsia. Both cardiac causes (e.g. ischaemic heart disease) and non-cardiac causes (e.g. GORD or oesophageal motility disorders) may be the underlying aetiology in these instances.

Upper abdominal complaints also occur frequently in patients with features compatible with other functional gastrointestinal disorders; irritable bowel syndrome is the commonest of these disorders (see Ch 7). Despite this overlap, approximately two-thirds of patients with dyspepsia and no peptic ulcer or other organic disease report a normal bowel habit, which suggests that they constitute a distinct group from irritable bowel syndrome.

‘Aerophagia’ refers to the repetitive pattern of swallowing air and belching to relieve the sensation of abdominal distension or bloating. It is best regarded as a specific functional gastroduodenal disorder and is considered further in Ch 8.

Differential diagnosis of dyspepsia

The differential diagnosis of dyspepsia is extremely wide, including diseases not only of the gastroduodenum, but also all of the other organs situated in the upper abdomen. Therefore, it is crucial to identify the precise symptoms. Leading questions are often required to elicit the complaints that trouble the patient most. Even when a detailed history has been obtained, the exact clinical diagnosis is often difficult—symptoms such as nocturnal waking, or relief or aggravation by eating often fail to discriminate between the different diagnoses. Patients with dyspepsia can, however, be subdivided into two main categories, based on the known or proposed underlying pathophysiology (Table 6.1). Thus dyspeptic symptoms may be ascribed to:

Table 6.1 Differential diagnosis of epigastric pain or meal-related epigastric discomfort

| Organic | Functional dyspepsia |

|---|---|

Chronic Peptic Ulcer

Chronic peptic ulcer, in most cases, is caused by H. pylori infection (Ch 5) or NSAIDs; an acid hypersecretory state (e.g. the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome due to a gastrin-producing tumour) is a rare but important cause to be aware of in practice.

Gastric cancer

A short history of new onset dyspepsia occurring in a patient over the age of 55 years should raise the suspicion of gastric cancer (Ch 17). Symptoms of pain or discomfort on a daily basis, together with early satiety, increase the probability. Weight loss, anorexia and vomiting are common symptoms, especially when the malignancy is advanced (hence not curable)—these are the alarm features or red flag symptoms. Dysphagia can occur with tumours arising from the cardia or distal oesophagus.

Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer

Similar symptoms of shorter duration, often with weight loss, may be associated with carcinoma of the pancreas, although this condition can typically present late when the patient is cachectic and jaundiced (Ch 23).

Cholelithiasis

‘Biliary colic’ is associated with the sudden onset of severe or very severe epigastric pain that may pass through or around to the back (Ch 4). Typically there are episodes of pain that occur unpredictably, usually with associated nausea and vomiting. With inflammation of the gall bladder, the pain may shift to the right upper quadrant and become ‘peritoneal’ in type. With biliary colic, movement does not aggravate the pain. The pain is usually not ‘colicky’ but sustained, albeit varying in intensity. Symptoms may be induced by a fatty meal. In the absence of typical biliary pain there appears to be no association between the presence of gallstones in the gall bladder and dyspepsia. If a gallstone enters the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis), there may be associated features of intermittent jaundice, dark urine, pale stools, or with sepsis episodic fever and rigors (see Ch 23).

Other causes

Intestinal ischaemia can sometimes cause dyspepsia. Intestinal or mesenteric angina causes the classical triad of upper abdominal pain induced by eating, a fear of eating (sitophobia), and weight loss (Ch 7).

Metabolic causes such as renal failure, hypercalcaemia or thyroid disease can at times present with dyspepsia. Dyspepsia can occur in patients with longstanding diabetes mellitus who have autonomic neuropathy, gastroparesis or diabetic radiculopathy. Other metabolic causes are discussed in Chapter 7. Referred pain from the chest or back may also occasionally cause chronic upper abdominal pain.

Management of Dyspepsia

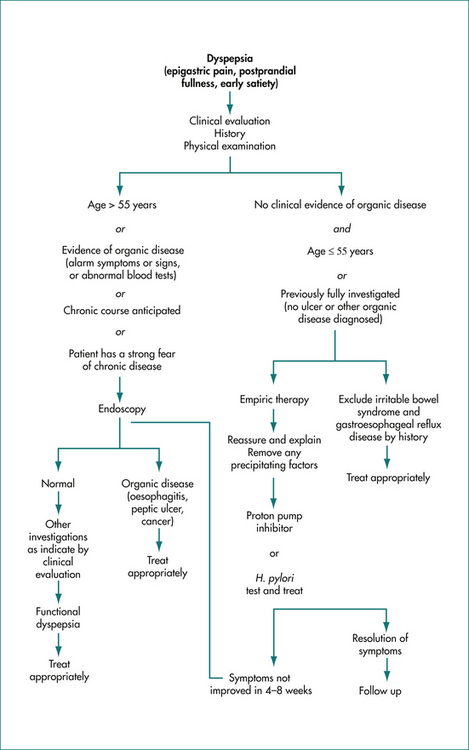

A careful history is important to document the symptoms; in particular gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and biliary disease can in most cases be readily suspected from the history and relevant further investigations and treatment undertaken. Otherwise, if there are no symptoms or signs to indicate a higher probability of organic disease, and the patient is under 55 years of age and is not taking regular aspirin or other NSAIDs, then immediate investigation is not warranted (Fig 6.1).