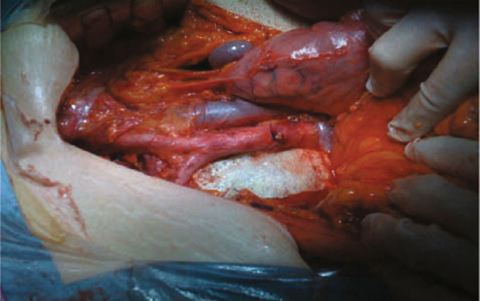

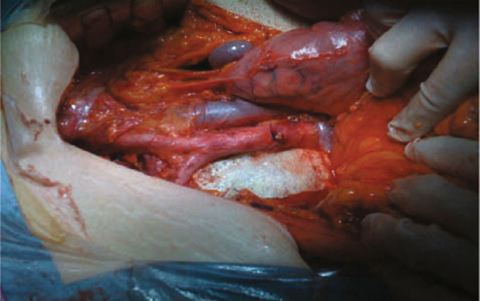

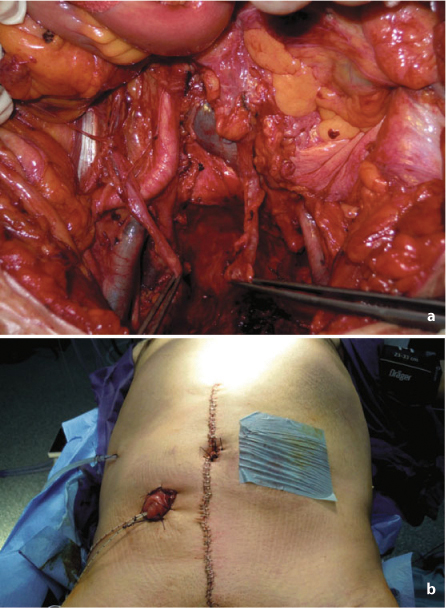

Fig. 7.1

Operative view after completion of extended (cylindrical) abdominoperineal resection

7.2 Role of Surgery

Obtaining a radical R0 resection is the most important prognostic factor related to improved oncologic outcomes in LRRC [5]. R0 resection is thus the main goal of the surgeon, but it can be accomplished in only 30–60% of patients selected for surgical exploration [6]. When radical resection is achievable, another major issue is to spare as many adjacent structures and organs as possible in order to help maintain the patient’s QoL.

7.2.1 Pelvic Exenterations

Extended radical resections, also defined as pelvic exenterations, include a variety of different procedures in which adjacent and surrounding anatomical structures are resected en bloc with the recurrent tumor. The type and number of organs and structures involved in the extended resections are strictly related to fixation sites and recurrent tumor location in the different pelvic compartments. Therefore, it is of crucial importance to evaluate preoperatively lesion resectability in each individual patient. Surgical resectability is usually defined as the possibility of obtaining an R0 resection (microscopically free from tumor invasion) with acceptable morbidity and mortality rates and with the additional benefit of a good QoL. A multidisciplinary team evaluation is mandatory to determine surgical resectability, and high-quality imaging and clinical data are essential to this purpose. In addition, in order to achieve an en bloc resection, the contribution or at least the prompt availability of other surgical specialists, including gynecologists, urologists, plastic surgeons, orthopedists, neurosurgeons, and vascular surgeons, is mandatory.

7.2.2 Patient Selection

In order to asses preoperatively the probability of achieving a beneficial radical resection, factors related to both the patient and the tumor must be taken into account. Apart from the technical resectability, a patient’s comorbidities and general status can preclude surgery, especially when planning major exenterative surgery. Extremely obese patients or the very elderly must be very carefully considered, since even when a radical resection can be hypothesized, morbidity and mortality rates are reported to be excessive [7]. Regardless, every candidate for multivisceral resection requires accurate preoperative optimization of performance status, which is essential in order to minimize morbidity. As can be extrapolated from various studies, male sex, advanced stage of the primary tumor, previous abdominoperineal resection (APR), high carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, and advanced age at initial diagnosis are all factors associated with a lower probability of obtaining an R0 resection. The presence of neural pain is also reported to be a factor that negatively impacts both R0 resection rate and oncologic outcomes [8]. In such cases, no survival benefits have been recognized, and in cases of attempted resection, postoperative QoL is reported to be very poor. In the past, palliative surgery was recommended to reduce symptoms and obtain pain relief, but at present, it is generally contraindicated, since such surgery is affected by a significant morbidity rate and generally offers very short-term pain relief. In addition, RT can offer similar local control, pain relief, and improved QoL. A major contraindication to surgery is a low probability of obtaining en bloc radical resection, and this is often the case in recurrences involving the lateral pelvic sidewalls.

The presence of extrapelvic disease is historically considered a contraindication to surgical exploration. In such cases, surgery is generally reserved for highly selected patients with a limited tumor burden in which radical resection can be obtained. Preoperative chemotherapy can help in testing tumor responsiveness and aggressiveness. Provided that a radical resection of both pelvic and extrapelvic disease can be attempted, surgery should be reserved to young, fit patients, since long-term outcomes of this policy remain unclear. Some authors [9] reported acceptable survival rates in selected patients with limited extrapelvic disease (mainly liver metastases), achieving a 5-year survival of 42% in patients who had an R0 resection [10]. From a technical point of view, tumor location and degree of local invasion are probably the main factors affecting resectability rate. Centrally (axial) and anteriorly located recurrences are, in fact, associated with a relatively high resectability rate (72–90%) in many series [11]. On the other hand, laterally located recurrences involving the pelvic side-walls have a very low resectability rate, with an R0 resection rate only accomplished in 6–36% of cases [11, 12]. This variation in resectability is a direct consequence of the invasion of different organs and anatomical structures contained in the pelvic compartments. In fact, when structures such as major iliac vessels or the sciatic notch are involved, ultraradical (extended radical) resections can be attempted only in carefully selected cases, and even so, often at the price of high morbidity rates and invalidating functional impairments without showing clear evidence of an oncological benefit.

Another important factor influencing prognosis and resectability rate is strongly related to the number of pelvic compartments involved and degree of tumor infiltration. The Royal Marsden Hospital group proposed a new classification system [13] with the aim of correlating the site of LRRC and survival outcomes after surgical resection. This classification is based on the degree of tumor invasion within the different pelvic compartments as visualized at preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). With the aid of MRI, the pelvis can be divided into seven different compartments reflecting dissection planes between pelvic organs and fascial boundaries (central [C], posterior [P], inferior [I], anterior above [AA] and below [AB] the peritoneal reflection, lateral [L], and peritoneal reflection [PR]). The latter classification is now widely applied in Europe and needs prospective validation in multicenter studies.

In the past, sacral involvement by a fixed pelvic recurrence was considered a relative contraindication to surgical resection. The level of infiltration is crucial to assess the resectability for nowadays concomitant sacral resection is generally feasible without excessive morbidity or significant QoL impairment when performed below the S2 level [14, 15]. On the contrary, sacral resection at S1–S2 is a relative contraindication, since a very high morbidity rate is reported due to nerve-root involvement at this level [16]; in addition, bony involvement at S1–S2 is generally associated with massive vascular (iliac vessels) and ureteral infiltration. Concomitant bone resection at this level leads to major sacroiliac instability requiring internal fixation. Nevertheless, it must be considered that even with an accurate evaluation by the expert multidisciplinary team and excellent imaging, effective resectability can be reliably assessed in most cases only at surgery [17]. The point is that, due to the significant morbidity rate and QoL impairment associated with extended procedures, careful selection of patients is mandatory before planning surgery, since only a clear survival benefit justifies the risks of such challenging procedures.

7.3 Surgical Techniques

The patient is placed in the modified Lloyd-Davies position and marked for bilateral stomas. The surgical team must always be prepared to flip the patient to the prone position to facilitate sacral resection and extended APR procedure, if indicated. Preoperative placement of ureteral stents can facilitate surgical dissection, since most patients have previously undergone pelvic surgery and/or radiation therapy, which can make it difficult to identify anatomical structures. A standard midline incision is generally performed, and after adhesiolysis, the presence of metastatic disease and any other contraindication to surgery is ruled out. Careful assessment of tumor extension and resectability is then performed. When resection is indicated, the likelihood of obtaining an R0 resection must be balanced against the sacrifice of involved pelvic organs and the future QoL before proceeding with surgery. If a portion of the colon or any ileal loop is infiltrated, an en bloc resection is planned. Pelvic dissection is generally facilitated by starting distant from the tumor and strong adhesions and is preferably carried out in an extraperitoneal plane, similarly to the technique of pelvic peritonectomy (Fig. 7.2). This facilitates en bloc resection and maximizes the radicality of the procedure. If invasion is suspected, iliac vessels and ureters are identified early in the procedure and looped cranially as distant from the tumor as possible. The sigmoid and descending colon can be divided in order to facilitate posterior dissection.

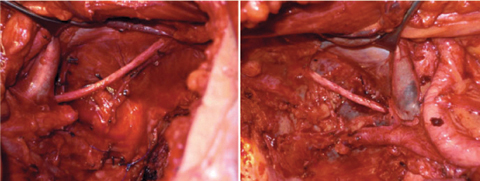

Fig. 7.2

Operative field after extended aortocaval lymphadenectomy

With a lateral pelvic recurrence, internal iliac vessels can be ligated, divided, and resected en bloc with the tumor. When vascular resections are performed, dissection must be carried out away from the tumor but deeply in the lateral pelvic walls. Structures, such as obturator nerve and posterior lumbosacral plexus, must be identified (Fig. 7.3). If lateral pelvic sidewall dissection must be carried out caudally into the pelvis, pelvic-floor and piriform muscles must be removed whenever invasion is suspected.

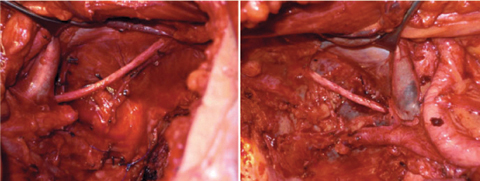

Fig. 7.3

Operative view after completion of bilateral lymphadenectomy of obturator fossa

Different sites and degree of ureter involvement can be present and deserve tailored resection and reconstruction. Segmental resection and direct reconstruction can be performed for limited invasion, but reimplantation into the bladder or reconstruction with an ileal conduct may be needed (Fig. 7.4). When very proximal massive monolateral ureter involvement is present, nephrectomy can be considered.

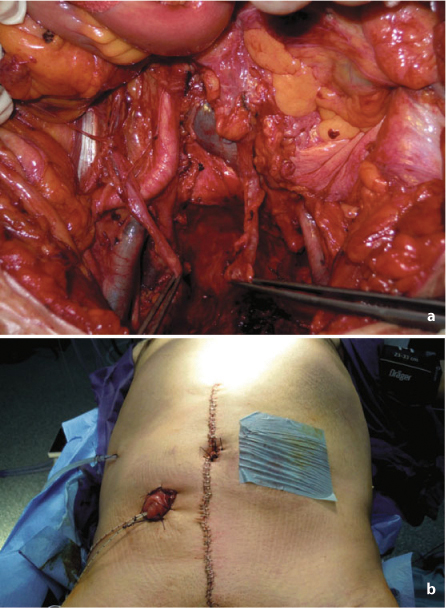

Fig. 7.4

a Operative field after completion of anterior pelvic exenteration. b Creation of bilateral stomas for colonic and urinary diversion after anterior pelvic exenteration

Anterior pelvic exenteration is performed according to the patient’s sex and the site of tumor fixation. In the female patient, hysterectomy is mandatory in case of direct tumor involvement or to gain access to the upper vagina if it is infiltrated. When a partial colpectomy (sparing ~50% of the organ) is performed, the vagina can be usually closed. Conversely, when a total colpectomy is needed, reconstruction with a myocutaneous flap is warranted. In the male patient, cystoprostatectomy is indicated if invasion of the bladder neck or prostate is present. Even when partial cystectomy is performed, reconstruction with a colonic or ileal conduit is advisable, since very poor function must be expected.

When posterior pelvic exenteration is indicated, the sacral promontory is identified, and the level of sacral bone involvement is carefully assessed. The presacral plane is followed up to the level of invasion. The S2–S3 junction is considered in many centers as the level determining resectability, although some authors report the feasibility and radicality of resections cranial to the S2–S3 junction [18]. In any case, before sacral resection can be planned, involvement of sacral nerve roots and vessels must be assessed, and identifying nerve plexuses at the level of transection can be helpful. When sacral resection is decided upon, lateral and anterior pelvic dissection is performed; if perineal reconstruction with a vertical rectus abdominus myocutaneous (VRAM) flap is planned, the flap can be prepared before turning the patient to the prone position. Some authors also advocate preventive ligation of the internal iliac vessels before sacrectomy in order to minimize blood loss, which can sometimes be massive. Closure of the abdominal wall and stoma formation can also be anticipated, thus avoiding patient reversal to the lithotomy position after sacral resection is completed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree