5 Indications and Techniques for Vaginal Hysterectomy for Uterine Prolapse

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

5-1 Vaginal Hysterectomy for a Large Uterus Requiring Morcellation Techniques

5-2 Use of the LigaSure Device During Simple Vaginal Hysterectomy

5-3 Bilateral Oophorectomy at the Time of Vaginal Hysterectomy

5-4 McCall Culdoplasty After Vaginal Hysterectomy

5-5 Simple Vaginal Hysterectomy for POP-Q Stage III Uterine Prolapse

5-6 Simple Vaginal Hysterectomy for POP-Q Stage II Uterine Prolapse

5-7 Simple Vaginal Hysterectomy for Uterine Procidentia With an Elongated Cervix

Uterine prolapse is multifactorial in most women, some of whom may be predisposed genetically. Direct damage to the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex as well as the levator ani muscular complex leads to loss of uterine and apical vaginal support. These defects can occur following pregnancy and childbirth or can develop in certain types of connective tissue disorders. Conditions associated with chronically elevated intraabdominal pressures may also contribute to POP, especially in cases of recurrence following prior surgical repair. These conditions include chronic constipation, a common symptom complex in aging patients; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; obesity; and occupations or situations associated with heavy lifting, such as caring for a disabled family member or spouse. Aging causes loss of muscular tone and dynamic function, decreased collagen quality, and endocrine abnormalities, which may play a role in POP.

Patient Selection

Simple vaginal hysterectomy is an ideal option for the postmenopausal woman with symptomatic uterine prolapse who desires definitive treatment and is not interested in uterine preservation. Concurrent apical suspension with anterior and/or posterior repair as well as antiincontinence procedures can also be performed if indicated. Sexual function can be maintained by giving careful attention to preservation of vaginal length, depth, and caliber. The vaginal approach is implemented more readily than the abdominal approach in obese patients as well as in patients who have undergone prior abdominal or pelvic surgery. Furthermore, vaginal hysterectomy with or without concurrent prolapse repair can be achieved under regional anesthesia, which may be ideal for any patient with compromised pulmonary function or cognitive dysfunction for whom general anesthesia is best avoided.

Surgical Anatomy

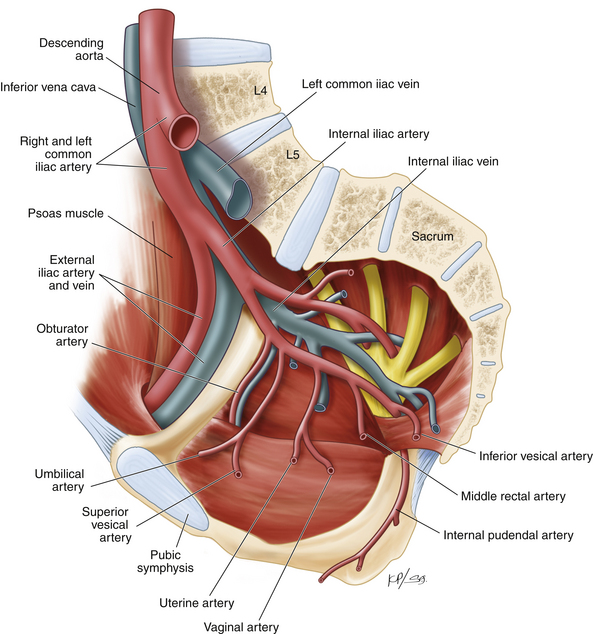

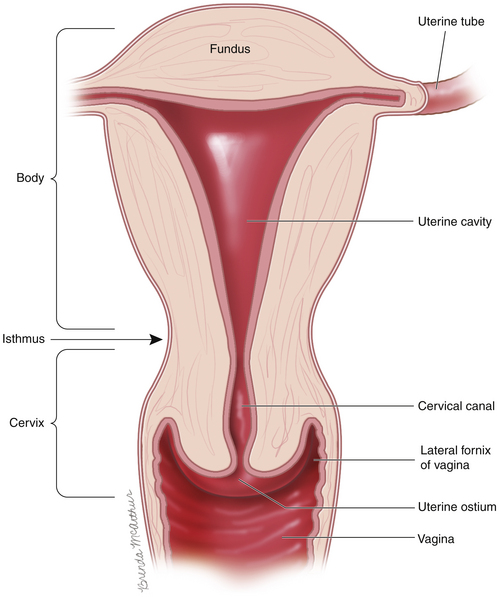

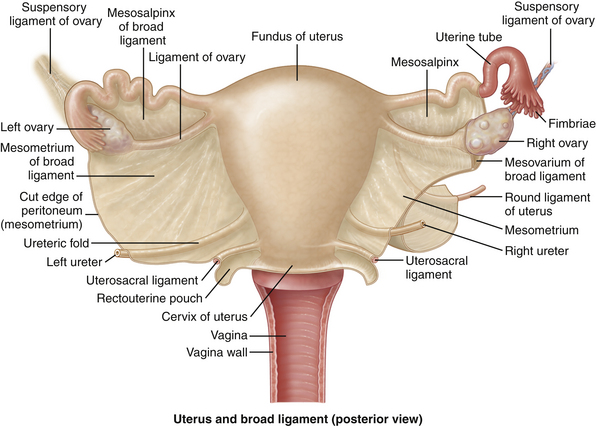

The uterus is composed of two main parts: the uterine corpus (or body) and the cervix. The corpus consists of the endometrial cavity surrounded by the myometrium and the serosa. The cervix, attached to the lateral fornices of the vagina, leads from the vagina to the endometrial cavity via the cervical canal (Fig. 5-1). The main support of the uterus comes from the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments. These two integrated connective tissue structures extend from their origin at the cervix and upper vagina to the pelvic sidewall (cardinal ligament) and to the sacrum (uterosacral ligament) and provide level I support for the uterus. Above these support structures lies the broad ligament composed of anterior and posterior leaves of visceral and parietal peritoneum that connect the uterus to the adnexa (Fig. 5-2). The blood supply to the uterus comes from branches of the internal iliac artery (Fig. 5-3). The uterine artery travels through the cardinal ligament and crosses over the ureter 1 to 2 cm lateral to the cervix. Before it enters into the uterus near the junction of the corpus and the cervix, the uterine artery sends off the vaginal artery, which supplies the upper portion of the vagina (see Fig. 5-3). The ovarian arteries are direct branches of the aorta.

Figure 5-1 Sagittal view of the uterus, cervix, and vagina.

(From Walters MD, Barber MD. Hysterectomy for Benign Disease. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010. Female Pelvic Surgery Video Atlas Series.)

Figure 5-2 Closer view of the uterus, cervix, ovaries, fallopian tubes, and the broad ligament.

(From Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM, et al. Gray’s Atlas of Anatomy. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2008:229.)

Surgical Technique for Simple Vaginal Hysterectomy

In this section we limit our discussion to vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of POP. This technique (with some modifications) can be applied to uterine prolapse of varying degrees (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification [POP-Q] stages II to IV) and uteri of different sizes. In addition the technique can be combined with vaginal oophorectomy when desired. In all cases in which vaginal hysterectomy is performed for the repair of POP, a procedure to address the cul-de-sac and restore and/or maintain apical support is necessary. (See Chapter 6 for discussion and demonstration of vaginal repair of enterocele and apical prolapse.)

1. After anesthesia is induced, lower-extremity sequential compression devices are applied, and the patient is placed in the exaggerated dorsal lithotomy position. Surgical preparation and draping are performed in the usual sterile fashion. We prefer to use an “all-in-one” lithotomy drape that includes leg covers and a midline subvaginal pouch to drain blood and fluids intraoperatively. The drape may be sutured to the perineum with silk sutures to avoid exposure of the anus in the operative field.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree