Implantable sacral nerve stimulation is a minimally invasive, durable, and reversible procedure for patients with urinary urge and fecal incontinence who are refractory to conservative therapy. The therapy is safe compared with other surgical options. An intact external or internal rectal sphincter is not a prerequisite for success in patients with fecal incontinence.

- •

Implantable sacral nerve stimulation is a mainstay of therapy for patients with urinary urge incontinence that have failed conservative therapy.

- •

Implantable SNS is now part of the treatment algorithm for patients with fecal incontinence, superseding sphincterplasty.

- •

The best practices and technological advances reviewed in this manuscript have reduced the revision rates, explantation rates and loss of effect.

This article is not certified for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ because product brand names are included in the educational content. The Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education requires the use of generic names and or drug/product classes as the required nomenclature for therapeutic options in continuing medical education.

For more information, please go to www.accme.org and review the Standards of Commercial Support.

Introduction and historical background

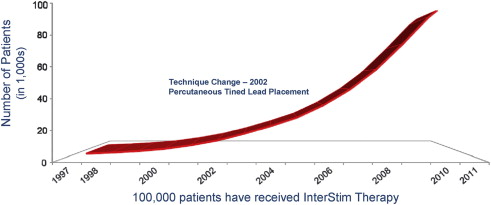

Implantable sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) is now a mainstay of therapy for patients with urinary urge incontinence who fail conservative therapy ( Fig. 1 ). Its value for patients with fecal incontinence is now recognized. SNS modulates the neural reflexes, which influence the bladder, urinary and rectal sphincters, and pelvic floor. Neuromodulation is the effect achieved by the SNS, and can result in either stimulation or inhibition. Other modalities of neuromodulation include physical therapy (PT) and medications.

Research has allowed development of an implantable SNS system to treat lower urinary track dysfunction. The University of California, Department of Urology in San Francisco, began the clinical program in 1981. A multicenter trial was performed from 1985 to 1992. The SNS approach was Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in 1997. Medtronic InterStim Therapy System (Medtronic Inc., 710 Medtronic Parkway NE, Minneapolis, MN, USA) is the only SNS system available to clinicians. Before use in the United States, Medtronic received CE (Conformité Européenne) marking for InterStim Therapy in 1994 in Europe to treat pelvic floor disorders. In 1999, the InterStim indications were expanded in the United States to include urinary urgency-frequency, and urinary retention. On March 14, 2011, Medtronic received premarket approval for the indication of fecal incontinence.

A unique collaborative atmosphere surrounded the introduction of this therapy. In 2002, a new society was formed, including all who are interested in pelvic floor disorders. The first meeting of The International Society of Pelvic Neuromodulation was held in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. The society comprised physicians, researchers, physical therapists, and other care providers with interest in pelvic floor disorders. The group merged with the Society of Urodynamics and Female Urology (SUFU) in 2008. The group continues its mission within the annual SUFU meetings. Interactions of the members of this group with Medtronic have led to significant improvement in the technology and refinements of InterStim technique.

This article discusses the topic from the urogynecology perspective. The urologic perspective is discussed by Dr Ken Peters elsewhere in this issue. This article summarizes best practices of implantable neuromodulation (ie, SNS) for urinary urge incontinence and fecal incontinence.

Mechanism of action: SNS

The effectiveness of SNS has been established by many publications for urinary and fecal incontinence ; however, the mechanism of action that provides beneficial therapeutic effects remains unclear. Amend and colleagues recently highlighted the current understanding of mechanisms of action, and the reader is referred to this comprehensive review. SNS likely exerts its influence by alteration of sacral afferent inflow on storage and emptying reflexes. Therapy likely modulates the central nervous system at the level where switching between bladder emptying and storage occurs.

Anal rectal function studies have revealed changes in both rectal motor function and rectal sensory function. In particular, balloon distension shows a decrease for the threshold of first urge. The patient is able to sense the presence of rectal contents at lower volumes, which allows the patient more time to respond to the urge to defecate. There seems to be no significant change in the resting pressure of the rectal sphincter, and mixed findings concerning increase in generated squeeze pressure. Stimulation of S2 to S4 and the pudendal nerve seems to excite the autonomic and somatic nervous systems, which causes both direct and reflex-mediated responses in the fecal continence mechanism.

Mechanism of action: SNS

The effectiveness of SNS has been established by many publications for urinary and fecal incontinence ; however, the mechanism of action that provides beneficial therapeutic effects remains unclear. Amend and colleagues recently highlighted the current understanding of mechanisms of action, and the reader is referred to this comprehensive review. SNS likely exerts its influence by alteration of sacral afferent inflow on storage and emptying reflexes. Therapy likely modulates the central nervous system at the level where switching between bladder emptying and storage occurs.

Anal rectal function studies have revealed changes in both rectal motor function and rectal sensory function. In particular, balloon distension shows a decrease for the threshold of first urge. The patient is able to sense the presence of rectal contents at lower volumes, which allows the patient more time to respond to the urge to defecate. There seems to be no significant change in the resting pressure of the rectal sphincter, and mixed findings concerning increase in generated squeeze pressure. Stimulation of S2 to S4 and the pudendal nerve seems to excite the autonomic and somatic nervous systems, which causes both direct and reflex-mediated responses in the fecal continence mechanism.

Results and cost-effectiveness: urge incontinence, fecal incontinence

A 2009 Cochran Review (urinary) cited 17 case reports with a 39% cure, and 67% reported an improvement of greater than 50%. The randomized trials reviewed reported 50% cure or improvement of greater than 90%. Greater than 80% had at least a 50% cure. The Cochran review and a review by Brazzelli and colleagues noted that there was no important difference between case study results and randomized studies.

A meta-analysis was performed on 34 studies with more than 700 patients treated for fecal incontinence from 2000 to 2008. The report showed improved functional outcomes and quality of life. The effect was prolonged, even in patients with anal sphincter defects. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of SNS for fecal incontinence has been reaffirmed in multiple publications. All reports show effectiveness beyond other surgical options, between 70% and 90%, with far less morbidity.

A recent cost analysis was performed in France for patients with urinary and fecal incontinence. They found that the initial cost was similar for urinary and fecal incontinence. The results within the French health system showed that SNS is a cost-effective treatment of both indications, compared with the alternatives. The investigators emphasized the possibility that different heath care systems and countries may have other findings.

An article in 2009 comparing the cost of SNS and medications concluded that SNS should be discussed early with the patients because of poor patient compliance with medications.

Patient selection: urinary urge incontinence

Women or men with urinary urge incontinence who do not achieve an adequate quality of life with conservative therapy are candidates for SNS. Each state and insurance carrier can vary in what is meant by a trial of conservative therapy; conservative therapy generally includes the use of medications and some form of pelvic floor PT ( Table 1 ).

| Behavioral and PT | Medications |

|---|---|

| Dietary restrictions | Alter medications if opportunity exists |

| Bowel regulation | Hormone replacement therapy |

| Fluid management | Antimuscarinic: tolterodine |

| Bladder drills/timed voiding | Mixed action medications |

| Kegal (cones) | Oxybutynin plus direct muscle relaxant and local anesthetic |

| Biofeedback/pelvic floor retraining |

The basic evaluation should include a bladder diary, focused history, pelvic examination, evaluation for postvoiding residual and urine analysis with culture and sensitivity ( Table 2 ). If there is a working diagnosis of urge incontinence, then conservative therapy can be initiated. If a working diagnosis cannot be established, other comorbidities exist (multiple surgeries, endocrine and or neurologic disorders, metabolic syndrome), or, the patient fails conservative therapy, then the clinician should proceed to additional testing. First-line additional testing includes an office cystoscopy and urodynamics. Other evaluations would be added depending on concerns. Consultation from the appropriate specialty helps to identify contributing conditions. When conservative therapy fails, SNS can be trialed.

| Focused Medical/Neurologic/Genitourinary History | Physical Examination |

|---|---|

| Medication | Abdominal examination |

| Associated symptoms and factors | Pelvic examination: atrophy, prolapse, levator pain, hypermobility |

| Duration and characteristics | Rectal sensation, tone, ability to generate a volume contraction |

| Frequency, timing, and amounts | Postvoid residual urinalysis and culture and sensitivity |

| Precipitants and antecedents (ie, surgery) | |

| Lower urinary tract symptoms | |

| Alterations in bowel |

Patient selection: fecal incontinence

Patient selection for fecal incontinence is similar to that for urinary dysfunction. First, there is an attempt at conservative therapy. The basic evaluation involves the use of a bowel diary to establish a baseline. The history can help identify conditions that can contribute to the problem. The physical examination can identify other pelvic floor issues, such as genital prolapse and/or rectal prolapse, and provide an assessment of the rectal sphincter function. Based on the findings of the basic examination, the patient may need the surveillance colonoscopy updated, or other gastroenterology, neurologic, or metabolic evaluation. Conservative therapy can be initiated at this point. Conservative therapy includes dietary modification, dietary bulking, medications such as antidiarrheal agents, pelvic floor PT, and biofeedback ( Box 1 ). If there is no improvement then SNS can be offered.

Diet advice (avoidance)

Rectal emptying

Glycerine, bisacodyl, phosphate enema

Biofeedback/pelvic floor retraining

Constipating agents

Codeine, loperamide, lomotil, bulk agents

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree