and Christopher Isles2

(1)

Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

(2)

Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary, Dumfries, UK

Q1 How does your knowledge of potassium homeostasis help in the diagnosis and management of hyperkalaemia?

The diagram we used in Chap. 1 to describe potassium homeostasis can also be used to illustrate the pathophysiology of hyperkalaemia. Dietary potassium is of the order 50–100 mmol/day. Most of this is stored intracellularly. Excretion is predominantly renal. Acute and chronic kidney injury are important causes of hyperkalaemia as is the acidosis of acute illness. Figure 18.1 also suggests three ways in which potassium may be driven back into cells: by insulin, by beta agonists such as salbutamol and by correction of acidosis.

Fig. 18.1

Potassium homeostasis

Q2 What is the normal range for serum potassium and at what point would you regard a patient as being hyperkalaemic?

The normal range is 3.5–5.4 mmol/l. The latest UK Renal Guidelines define hyperkalaemia as mild (serum K+ 5.5–5.9 mmol/l), moderate (serum K+ 6.0–6.4 mmol/l) or severe (serum K+ ≥6.5 mmol/l). Others use 7.0 mmol/l as the threshold for severe hyperkalaemia. It probably doesn’t matter hugely whether 6.5 mmol/l or 7.0 mmol/l is taken as a cut point. What matters more is the rate at which serum potassium is rising and the likelihood it will rise further.

Q3 Give the causes of hyperkalaemia.

The most important are acute and chronic renal failure. Many of the other causes begin with A as shown in Box 18.1. This list is not intended to be exhaustive. For a more complete list of all drugs associated with hyperkalaemia, see the Renal Association guideline.

Box 18.1 Causes of Hyperkalaemia

Acute and chronic kidney injury

Adrenal failure

Acidosis

Artefact (haemolysis)

ACE inhibitor

Angiotensin receptor blocker

Aldosterone antagonist (spironolactone)

Anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

Antibiotic (specifically trimethoprim)

Q4 What are the risks of hyperkalaemia?

Many medical students answer this question by saying ‘arrhythmia’. This is not precise enough. The particular risk of hyperkalaemia is death by asystole or VF. Narrow complex tachycardia including atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia and idioventricular rhythms have also been reported.

Q5 How does hyperkalaemia present clinically?

Sudden death is common as many patients will be completely asymptomatic until they present with asystole or VF. Others may complain of nausea, fatigue, muscle weakness or paraesthesia before developing such serious complications.

Q6 What are the ECG changes of hyperkalaemia?

Although the pattern of ECG changes can vary from patient to patient the following sequence is most commonly seen:

Box 18.2 Common Sequence of ECG Changes with Increasing Hyperkalaemia

1.

Peaked T waves are an early sign

2.

Loss of the P wave

3.

Widening of the QRS complex

4.

Bradycardia

5.

Asystole

The ECG will usually be available before the serum biochemistry. You should suspect life threatening hyperkalaemia if an ECG shows bradycardia, broad complexes and no obvious P waves. The absence of P waves distinguishes life threatening hyperkalaemia from complete heart block (Fig. 18.2).

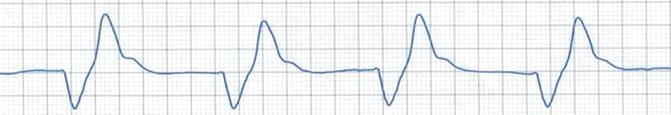

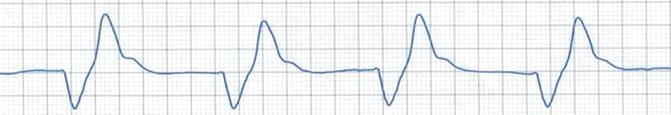

Fig. 18.2

ECG changes of hyperkalaemia (Note peaked T waves, absence of P waves, broad QRS and profound bradycardia)

Q7 When should you treat hyperkalaemia?

The decision to treat should be based on the level of potassium, the likelihood it will rise further and the presence of ECG changes. In practice this means always treating when serum K ≥6.5 mmol/l and usually treating when serum K is 6.0–6.4 mmol/l (Fig. 18.3).

Fig. 18.3

Factors influencing treatment choices in hyperkalaemia

Q8 How would you treat hyperkalaemia in the acute setting?< div class='tao-gold-member'>Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree