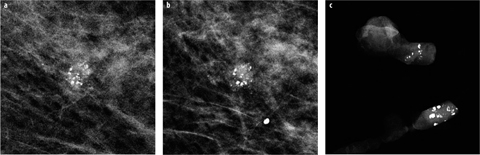

Fig. 1 a–c

Spectrum of histologically confirmed a benign and b, c malignant calcifications. There is a large overlap, especially between benign changes (a) and low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DISC) (b). c High-grade DCIS is more likely associated with calcifications with higher probability of malignancy

Artefacts and Changes Mimicking Breast Calcifications

It is important to realize that a number of artefacts, foreign material outside of breast and skin changes, may mimic suspicious breast calcifications. Typical examples are aluminium-based deodorants, zinc-containing skin ointments, calcifications within skin lesions (e.g., seborrheic warts) or benign calcifications within or on the surface of the skin. If it is unclear whether a calcification is actually located within the breast or on the surface, additional tangential views may be employed to demonstrate or exclude skin calcifications [5] (Fig. 2).

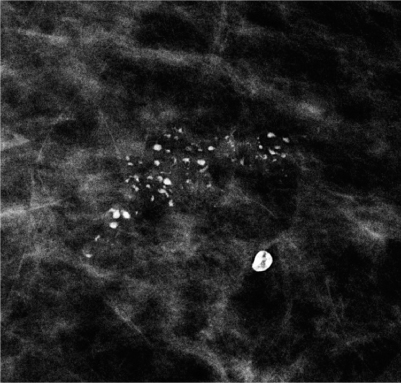

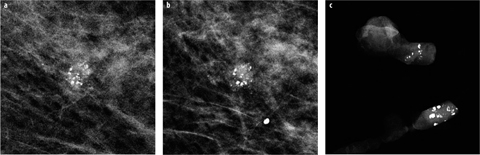

Fig. 2 a,b

a Small group of suspicious calcifications in the left breast seen on a magnification view. b Additional tangential view clearly demonstrates the superficial location of the calcifications on the skin surface, definitively proving their benign nature

Size

Oftentimes, breast calcifications are separated into larger (usually benign) macrocalcifications and smaller (possibly malignant) microcalcifications [6]. Usually, a size threshold of somewhere between 0.5 and 2 mm is used to distinguish between micro- and macrocalcifications; however, no clear guidelines for this exist [2, 7, 8]. The smallest calcifications visible on mammography have a size of ~0.1 mm [9, 10], although this will vary somewhat with the type of imaging system and parameters used as well as breast density and compressed thickness.

As histopathology is able to identify calcifications much smaller than this 0.1-mm threshold for calcification visibility on mammography, it is important for accurate radiologic-pathologic correlation to specify the size of calcifications seen on histopathology. The cooccurrence of very small microcalcifications at the mammographic detection threshold and larger calcifications within the same cluster increases the likelihood of malignancy (Fig. 3). Benign microcalcifications, e.g., in sclerosing adenosis, are more likely uniform in size.

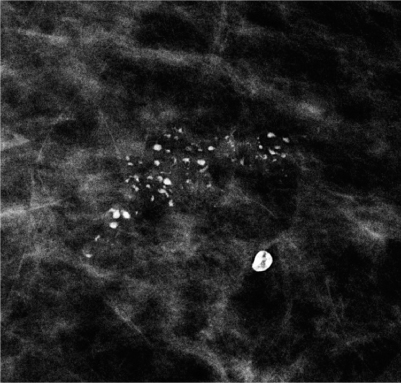

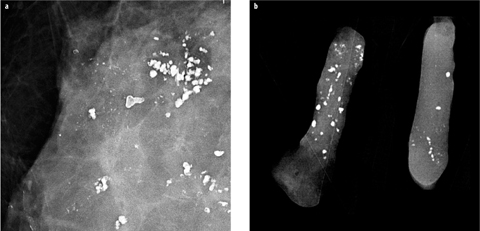

Fig. 3

Group of suspicious calcifications with coarse, heterogeneous morphology and varying individual sizes in a case of highgrade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). In the vicinity, a typical benign macrocalcification is seen

Number

The likelihood of calcification malignancy is strongly dependent on the number of calcifications within a certain area. Typically, a minimum of five calcifications within a cubic centimeter is considered sufficient to define a group (cluster) of calcifications in which malignancy should at least be considered [8]. Individual, loosely distributed calcifications are almost always benign. Only in very rare instances may biopsy be required in diagnosing groups with fewer than five calcifications, e.g., if the individual calcifications are highly suspicious of malignancy based on morphology. The more individual calcifications are found within a group of calcifications, the higher the probability of malignancy [8]. In malignant calcifications, the magnification views will often show additional small calcifications (Fig. 4), whereas in benign cases, the number of individual calcifications in a cluster will typically be similar in the overview image as well as in the magnification view. The only exception are amorphous (powder-like) benign calcifications typically found in sclerosing adenosis, in which numerous, very small (usually at or below the detection threshold of mammography) calcifications are tightly packed within a small area. Sometimes, these are only detected on mammography because multiple overlying calcifications within the group add up to a sufficient density to be visible on mammography.

Fig. 4 a–c

a Small group of suspicious calcifications of varying size and shape detected on screening mammography. b On the additional magnification view, the shape of the calcifications is much better defined, and additional smaller calcifications are seen. c Vacuum- assisted stereotactic biopsy with specimen radiography was performed, confirming a high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

Morphology

Calcification morphology is probably one of the strongest predictors of malignancy. Typically benign calcifications are popcorn-like coarse calcifications commonly encountered in involuting fibroadenomas; coarse foreign body (suture), or coarse dystrophic (posttraumatic) calcifications; tram-like vascular calcifications; benign, rodlike, periductal calcifications [11]; skin calcifications with lucent center; small cysts with milk-of-calcium deposits; and fat necrosis with eggshell or rim calcifications [1, 2, 8]. Round or punctate (lobular) calcifications, especially those with diffuse, bilateral distribution, are also very likely to be benign, although small, isolated clusters of round calcifications may sometimes represent malignancy and should at least be placed on short-term follow-up if not biopsied. Calcifications with high probability of malignancy that more often encountered in high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (Fig. 1c) are fine pleomorphic or linear-branching calcifications [12, 13]. All other calcifications, which cannot be classified as either typically benign or highly suspicious of malignancy, are of intermediate concern. Typical examples of this category are coarse heterogeneous (Fig. 3) and amorphous (indistinct) calcifications [14]. Unless size stability over a longer period of time (usually at least 5 years) can be demonstrated, these calcifications usually require histological confirmation to exclude malignancy. Often, additional views (e.g., spot magnification, mediolateral view) are necessary to reliably categorize calcification morphology. If calcifications with different morphology are present within the same area, the decision whether to perform biopsy should be based on the most suspicious calcifications present.

Distribution

Calcification distribution is an important factor in distinguishing between benign and malignant calcifications. Linear, segmental, clustered, and — to a lesser degree — regional distribution may indicate malignancy, whereas diffuse scattered, especially bilateral, distribution is usually, but not always, associated with benign disease [15]. Careful follow-up of cases with extensive calcifications should be performed to exclude malignancy developing within an area of preexisting benign calcifications (Fig. 5). In particular, sclerosing adenosis, columnar-cell change, and low-grade DCIS may sometimes coexist within the same area of calcifications.

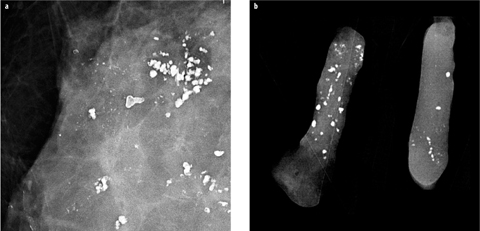

Fig. 5 a,b

Patient with known extensive, bilateral, coarse, dystrophic, benign calcifications. a In one area, additional suspicious fine pleomorphic and linear microcalcifications developed. b Stereotactic vacuum-assisted biopsy confirmed high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with focal invasion

Change Over Time

Interval progression of calcifications within a defined area may indicate malignancy, especially if the number of individual calcifications and the size of the involved area increase over time. If just the size of the individual existing calcifications increases but the number does not, the underlying abnormality will usually be benign (e.g., an increasingly calcified fibroadenoma or fat necrosis). Diagnostic difficulties may occur when a benign lesion such as a fibroadenoma is just beginning to calcify. In these cases, a short-term follow-up may be helpful to define more clearly the benign nature of the calcifications. Due to the sometimes very slow growth of DCIS, even documented calcification stability over a period of 2–3 years may not entirely rule out malignancy. Another potential pitfall is suspicious but stable calcifications within dense breast parenchyma, as progression of a noncalcified (invasive) tumour component may go undetected on mammography due to the surrounding dense breast parenchyma. In these cases, additional imaging such as ultrasound (US) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be beneficial.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree