Vasectomy as a medical term is a misnomer because only part of the vas deferens is excised during the procedure. Vas deferens as an anatomic structure was not a subject of significant clinical and research interest until the nineteenth century. It is difficult to find another surgical procedure as simple as vasectomy that has sparked so much medical and social controversies for more than a century. Vasectomy is a historical, social, philosophic, medical, demographic, and legal phenomenon. It is not surprising that the history of this procedure combines not only a constant quest for ideal technique and better results but also misconceptions, false beliefs, and erroneous indications.

Vasectomy as a medical term is a misnomer because only part of the vas deferens is excised during the procedure. It has been used in the literature to describe a wide range of procedures including partial vasectomy, vasal transection, vasoligation, and vasal occlusion. Vas deferens as an anatomic structure was not a subject of significant clinical and research interest until the nineteenth century. It is difficult, however, to find another surgical procedure as simple as vasectomy that has sparked so much medical and social controversies for more than a century. Vasectomy is a historical, social, philosophic, medical, demographic, and legal phenomenon. It is not surprising that the history of this procedure combines not only a constant quest for ideal technique and better results but also misconceptions, false beliefs, and erroneous indications.

Early experimental and clinical works on vasectomy

Herophilus (335 bc –280 bc ) provided the first account of the testicles, epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicles, spermatic artery, and spermatic vein. The vas deferens was first mentioned much later by another ancient physician, Rufus of Ephesus (late first century ad ), in one of the first known books on anatomic nomenclature “De nominatione partium hominis” (“On the naming of the parts of the body”), where it was called Πo´ρoí σπερματíκoí. For the following centuries, the amount of neologisms in anatomy was unprecedented because it was necessary to describe and name new things. Thus, vas deferens as a structure in the ancient literature was called “ evacuatorium” or “ expulsorium seminis ,” “ vas nervosum ,” “ canales” or “ pori ,” even “ itinera seminaria” or “ venae genitals ,” all of these being different versions of the Greek translation of “ poroi spermatikoi .”

Vas deferens (vās, duct + in dēferēns, present participle of dēferre, to carry away) was supposedly named by Mondino dei Liuzzi or Mundinus (1275–1327), anatomist from Bologna. His book “De Anatome” (Anothomia) was published in 1316 and widely used in European medical schools for more than 300 years. In the chapter “De anothomia vasorum spermaticorum et testiculorum,” he described vasa spermatica praeparantia (semen-preparing vessels that carry semen to the testes) and vasa spermatica deferentia (semen-delivering vessels), that carried semen away from the testes ( Fig. 1 ). In his books “Commentary on the Anatomy of Mundinus” (1521) and the famous “Isagogae Brevis” (“A Short Introduction to Anatomy,” 1522), another famous Italian anatomist, Berengario da Carpi (1460–1530), mentioned the presence of descending vessels carrying sperm down to the testes and contiguous with them ascending vessels, vasa deferentia (vasa spermatica), which carry sperm away. “Their substance is white and harder than that of the other vessels. These vasa deferentia in the male ascend from the testes to the pubic bone… These vessels bent back within the belly descend between the rectum and the bladder, and there they dilate into many caverns…”

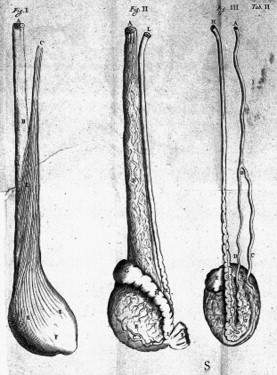

Regnier de Graaf (1641–1673) must be credited for the detailed description and the first experimental work on the vas deferens. In his book “De Vivorum Organis Generationi Inservientibus” (1668), he described vas semen deferens as a “body like large nerve, round white, rather hard and with manifest cavity. So that the cavity may be seen better, a vas deferens should be opened the breadth of 6 or 7 fingers above the testicle and air pumped in the direction of the testicle, or better a coloured liquid injected by means of syringe. The vessel will distend” ( Fig. 2 ). In his animal experiments, De Graaf “firmly bound the vas deferens of one testicle in a dog or some other animal before coitus” and then observed “the tubules of the testicle fill with seminal matter in such way that anyone at all can perceive them. ”

John Hunter first described absence of the vas deferens in a cadaver in 1737. More advanced experimental work on the vas deferens was performed by Sir Astley Cooper in the beginning of the nineteenth century. He found that ligation of the dog’s vas deferens, unlike ligation of the testicular artery and vein, does not produce a “gangrened and sloughed” testicle. Complete occlusion of the vas deferens caused enlargement of the testis and epididymis, which was also filled with spermatozoa. After 6 years of observation, spermatozoa were found in the epididymis, which confirmed intact sperm production after vasal occlusion.

The effect of vasectomy or vasal occlusion on spermatogenesis was studied later by many researchers with initially controversial reports. Working on dogs and rabbits, Gosselin and Brissaud noted normal spermatogenesis after ligation or resection of the vas deferens. Gosselin also dissected human cadavers and observed that entirely blocked vas deferens was associated with an enlarged epididymis that contained quantities of spermatozoa. These observations were confirmed by Curling in 1866. Bouin and Ancel (1903) declared that closing the outlet from the testis invariably leads to degeneration of the germinal tissue, however. This opinion was supported by works of Tiedje and Sand, who also used vasoligation in clinical practice. In 1924, Moore and Quick and then Oslund studied the effect of vasectomy on rabbits, rats, and guinea pigs. They concluded that vasectomy alone does not cause degeneration of germ cells. Clinical evidence of preserved spermatogenesis was provided by Posner, who reported that “by puncture of the testis he had withdrawn living spermatozoa 10–17 years after occlusion of the epididymis by gonorrheal invasion.” William Belfield, on making an anastomosis of epididymis and vas for cure of sterility, found spermatozoa present 14 years after the occlusion of the epididymis had occurred. By the first quarter of the twentieth century, research and clinical observation revealed no bad effects after vasectomy/vasal occlusion.

Vasectomy in clinical practice: the beginning

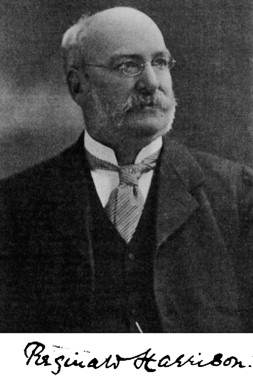

Clinical use of vasectomy can be traced back to the 1880s. Since the first orchiectomy was performed by Louis Auguste Mercier in 1857 for the treatment of enlarged prostate, castration has been used to reduce obstructive symptoms of prostatic hypertrophy and improve micturition. The earliest reference to section of vasa deferentia as an alternative procedure to castration to achieve prostatic atrophy was made by Felix Guyon in 1885 ( Fig. 3 ). Five years later, in 1890, James Ewing Mears also suggested vasectomy for the same reasons. Karl Gustav Lennander from Uppsala University (Sweden) advocated vasectomy as a substitute for castration “as a means of relieving ills consecutive to prostatic hypertrophy in 1894. Pavone and Isnardi described prostatic atrophy as a result of vasectomy. Reginald Harrison performed more than 100 vasectomies between 1893 and 1900 ( Fig. 4 ). He found that “the usual effect of vasectomy is to induce shrinkage of the hypertrophied prostate” and restore natural micturition. Harrison performed vasectomy by excision of the portion of the vas deferens but later substituted it with torsion of the vas deferens for vasal obliteration “with the pair of Spencer Wells forceps, through a small incision over the duct.” In this way, the vas is seized and bared and a small portion of it is torsed out, no ligature being required. A 7- or or 10-day interval in dealing with the two vasa is advised.” Harrison was probably the first physician who also noticed reconnection of the divided portion of the vas deferens. “It was found six months after a portion of one of the vasa had been excised and the ends ligatured in a loop that the divided ends had reunited and the continuity and use of the duct has been reestablished.” Vasectomy enjoyed popularity for a short time because it was considered a method of minimal harm and high efficacy.

Further experience, however, lowered the expectation of micturition improvement after vasectomy. In 1895, Guyon failed to obtain any substantial loss of the bulk of the prostate in four different experiments. Wood reviewed 192 cases of vasectomies and reported improvement in urination in 15%, no changes in 15%, and deaths in 6.7%. Wallace concluded that “a single or double vasectomy is useless as a means of producing prostatic atrophy.” Shortly afterwards, this method had lost its recognition as a treatment for prostatic hypertrophy, especially with further developments of surgical treatment of enlarged prostate.

Wood noticed that vasectomy was successfully performed for the relief of painful recurrent orchitis, which “quite justified this operation apart from any intention to affect the prostate.” Although prostatectomy has become a more commonly performed procedure, epididymitis was recognized as a far too frequent surgical complication. Vasectomy was recommended for prevention of postoperative epididymitis at the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1904, Robert Proust, a French urologist and brother of famous writer Marcel Proust, mentioned vasectomy at the time of prostatectomy. It was also recommended by Jose Albarran in 1909. Allea described a temporary through-the-skin vasoligation technique. This technique was discouraged because of difficulties feeling and isolating the vas, however. Meltzer (1928) recommended bilateral vasectomy, rather than vasoligation, as “a definitive prophylactic measure against the painful complication of epididymitis.” Scrotal vasectomy had been a popular—albeit controversial—procedure before, during, or after open prostatectomy and even transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for almost 80 years. With improved surgical techniques and new effective antibiotics, the incidence of epididymitis diminished drastically. One of the last prospective studies conducted in 1975 showed that vasectomy does not reduce the incidence of epididymitis and its routine use in prostatic surgery is not indicated.

Vasectomy in clinical practice: the beginning

Clinical use of vasectomy can be traced back to the 1880s. Since the first orchiectomy was performed by Louis Auguste Mercier in 1857 for the treatment of enlarged prostate, castration has been used to reduce obstructive symptoms of prostatic hypertrophy and improve micturition. The earliest reference to section of vasa deferentia as an alternative procedure to castration to achieve prostatic atrophy was made by Felix Guyon in 1885 ( Fig. 3 ). Five years later, in 1890, James Ewing Mears also suggested vasectomy for the same reasons. Karl Gustav Lennander from Uppsala University (Sweden) advocated vasectomy as a substitute for castration “as a means of relieving ills consecutive to prostatic hypertrophy in 1894. Pavone and Isnardi described prostatic atrophy as a result of vasectomy. Reginald Harrison performed more than 100 vasectomies between 1893 and 1900 ( Fig. 4 ). He found that “the usual effect of vasectomy is to induce shrinkage of the hypertrophied prostate” and restore natural micturition. Harrison performed vasectomy by excision of the portion of the vas deferens but later substituted it with torsion of the vas deferens for vasal obliteration “with the pair of Spencer Wells forceps, through a small incision over the duct.” In this way, the vas is seized and bared and a small portion of it is torsed out, no ligature being required. A 7- or or 10-day interval in dealing with the two vasa is advised.” Harrison was probably the first physician who also noticed reconnection of the divided portion of the vas deferens. “It was found six months after a portion of one of the vasa had been excised and the ends ligatured in a loop that the divided ends had reunited and the continuity and use of the duct has been reestablished.” Vasectomy enjoyed popularity for a short time because it was considered a method of minimal harm and high efficacy.

Further experience, however, lowered the expectation of micturition improvement after vasectomy. In 1895, Guyon failed to obtain any substantial loss of the bulk of the prostate in four different experiments. Wood reviewed 192 cases of vasectomies and reported improvement in urination in 15%, no changes in 15%, and deaths in 6.7%. Wallace concluded that “a single or double vasectomy is useless as a means of producing prostatic atrophy.” Shortly afterwards, this method had lost its recognition as a treatment for prostatic hypertrophy, especially with further developments of surgical treatment of enlarged prostate.

Wood noticed that vasectomy was successfully performed for the relief of painful recurrent orchitis, which “quite justified this operation apart from any intention to affect the prostate.” Although prostatectomy has become a more commonly performed procedure, epididymitis was recognized as a far too frequent surgical complication. Vasectomy was recommended for prevention of postoperative epididymitis at the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1904, Robert Proust, a French urologist and brother of famous writer Marcel Proust, mentioned vasectomy at the time of prostatectomy. It was also recommended by Jose Albarran in 1909. Allea described a temporary through-the-skin vasoligation technique. This technique was discouraged because of difficulties feeling and isolating the vas, however. Meltzer (1928) recommended bilateral vasectomy, rather than vasoligation, as “a definitive prophylactic measure against the painful complication of epididymitis.” Scrotal vasectomy had been a popular—albeit controversial—procedure before, during, or after open prostatectomy and even transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for almost 80 years. With improved surgical techniques and new effective antibiotics, the incidence of epididymitis diminished drastically. One of the last prospective studies conducted in 1975 showed that vasectomy does not reduce the incidence of epididymitis and its routine use in prostatic surgery is not indicated.

The fountain of youth

In the nineteenth century, Charles-Edouard Brown Sequard (1817–1894) coined the word “rejuvenation,” and the interest of defeating old age flourished in the early twentieth century. After 20 years of sophisticated animal research on testicular function, Eugen Steinach (1861–1944), an Austrian physiologist, professor of biology at the University of Vienna, and director of the city’s Biologic Institute of the Academy of Science, published his famous book ”Rejuvenation Through the Experimental Revitalization of the Aging Puberty Gland”(1920). He reported degeneration of the germinal epithelium and hypertrophy of the interstitial (Leydig) cells after unilateral vasectomy or vasoligation. This, in turn, stimulates the production of germ cells by the opposite testis and returns old animals to a functional condition. Steinach announced that he had rejuvenated a senile male rat with vasoligation and that the technique can be used on humans. Surgery of the vas deferens (vasectomy or vasoligation) was termed a Steinach I procedure; introduced later was the less popular ligation of the efferent ductules between testis and epididymis, known as a Steinach II operation ( Fig. 5 ).

On November 1, 1918, Dr. Robert Lichtenstern performed the Steinach procedure on Anton W., a 43-year-old coachman who suffered from chronic fatigue. “The patient presented with the appearance of an exhausted and prematurely old man,” Steinach reported in his book. The procedure resulted in long-lasting improvement. It brought Steinach world fame. In April 1923, the New York Times wrote about the “exodus to Vienna” of doctors who hoped to learn the secret of the Steinach operation.

Thousands of Steinach operations were performed in the United States and around the world. Before his planned visit to America, the New York Times wrote: “Dr. Steinach Coming to Make Old Young.” He was so famous that his name became a verb: men were “Steinached.” Eugen Steinach was nominated unsuccessfully for a Nobel Prize in physiology six times between 1921 and 1938.

On November 17,1923, the Viennese urologist Victor Blum performed a Steinach operation on Sigmund Freud, who “hoped that it might bar the recurrence of his jaw cancer and might even improved his sexuality, general condition and his capacity to work.” After the procedure, Freud was ambiguous about its effect. Another famous person, the Nobel Prize winner in literature W.B. Yeats, underwent a vasectomy on April 6, 1934, at the age of 69. “It revived my creative power and…sexual desire,” he wrote in 1937.

Medical views on the rejuvenation vasectomy procedure ranged from those of devotees, such as Robert Lichtenstern and Peter Schmidt in Germany, Harry Benjamin in America, and Norman Haire in England, to scoffers such as Morris Fishbein (1889–1976) the editor of JAMA . Fishbein denounced the Steinach procedure as early as 1927 with the lack of scientifically controlled studies. The procedure was in use until the late 1940s, however. Popularity of rejuvenation by vasectomy gradually declined after isolation of testosterone in 1935. In 1951, the most well-known proponent of the Steinach procedure, Norman Haire, accepted that his belief about rejuvenating consequence of vasectomy was faulty. The Simon Population Trust, a UK voluntary sterilization organization, declared that the Trust did not recommend vasectomy for rejuvenation only in 1969.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree