Hepatitis B virus (HBV) during pregnancy presents unique management challenges. Varying aspects of care must be considered, including the effects of HBV on maternal and fetal health, effects of pregnancy on the course of HBV infection, treatment of HBV during and after pregnancy, and prevention of perinatal infection. Antiretroviral therapy has not been associated with increased risk of birth defects or toxicity, but despite studies designed to elucidate the drug efficacy and safety in affected individuals and the developing fetus, recommendations are inconclusive. Clinicians and patients must make individualized decisions after carefully evaluating the risks and benefits summarized in this article.

Disease burden

An estimated 350 million people, 5% of the world’s population, are chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV); of those, 70% live in the western Pacific area. Despite global adoption of hepatitis B immunization programs over the past 2 decades, chronic HBV infection and its complications, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, remain significant medical and financial burdens to the health care system. The prevalence of HBV infection varies greatly among countries. In high endemic areas such as China, most of Africa, and South America, more than 10% of the population is infected.

In the United States, an estimated 1.4 million individuals are infected with HBV. Between 2000 and 2003, HBV infection was responsible for 2000 to 4000 deaths. Chronic HBV prevalence is the highest among immigrants from high endemic countries, people who have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, and household contacts of people with chronic HBV infection.

Mode of infection

HBV has two primary modes of transmission: from infected mother to newborn during delivery (vertical transmission) and from an infected sexual or household contact (horizontal transmission). Unlike adult-acquired HBV infection, in which the risk of chronic infection is only 5% to 10%, perinatally acquired infection carries an 85% to 95% risk of chronic infection, with a 25% to 30% lifetime risk of a serious complication or fatal liver disease.

In the United States, the incidence of new HBV infection has fallen 82% since the implementation of universal vaccination at birth in the early 1990s. Today, new infections occur mainly among unvaccinated adults. In the United States, vertical transmission is responsible for a very small fraction of new HBV infections; and of the 43,000 new infections in the United States each year, only 1000 are estimated to occur in children. Worldwide, however, 50% of chronically infected individuals acquired their infection perinatally or in early childhood, much of which is attributed to high rates of hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg)–positive infections in women of childbearing age.

Mode of infection

HBV has two primary modes of transmission: from infected mother to newborn during delivery (vertical transmission) and from an infected sexual or household contact (horizontal transmission). Unlike adult-acquired HBV infection, in which the risk of chronic infection is only 5% to 10%, perinatally acquired infection carries an 85% to 95% risk of chronic infection, with a 25% to 30% lifetime risk of a serious complication or fatal liver disease.

In the United States, the incidence of new HBV infection has fallen 82% since the implementation of universal vaccination at birth in the early 1990s. Today, new infections occur mainly among unvaccinated adults. In the United States, vertical transmission is responsible for a very small fraction of new HBV infections; and of the 43,000 new infections in the United States each year, only 1000 are estimated to occur in children. Worldwide, however, 50% of chronically infected individuals acquired their infection perinatally or in early childhood, much of which is attributed to high rates of hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg)–positive infections in women of childbearing age.

Prevention strategies

Vaccination at birth has been a successful strategy adopted by the United States and the rest of the world to prevent HBV infection. Immunization of the adult population has also been encouraged by some countries but has been deemed too costly. The vaccine is reserved for adults at high risk of acquiring the infection. Currently, 175 countries, or 91% of all nations, have a child immunization program. The modality and success of implementing a vaccination program vary greatly and depend on the country’s available resources.

The United States began an infant vaccination program in 1991, and a catch-up vaccination program in 1999 for every individual younger than 19 years of age. In 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a document describing future strategies to control and prevent HBV infection in the United States. Recommendations include an enhanced immunization schedule at birth, public education in collaboration with community-based programs, and targeted vaccination of high-risk adults.

Prevention of perinatal transmission: current recommendations

Universal HBV Prenatal Screening

The prevalence of chronic HBV infection in pregnant women in the United States varies by race and ethnicity, with Asian women having the highest rate of infection (6%). An estimated 24,000 HBV-infected women give birth in the United States each year.

In the United States, routine universal prenatal screening for HBV identifies women who are positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) before they give birth. This practice achieves two goals: newborns receive the appropriate postexposure prophylaxis, and infected mothers receive appropriate medical care during and after pregnancy. The delivery hospital functions as a safety net where all women of unknown status (lack of evidence of HBV testing) are required to be tested on admission. This program has been successful, with 97% of all pregnant women currently tested before childbirth. Universal screening of pregnant women is not practiced in every country. Many European countries, for example, still practice screening models driven by risk factors.

The hepatitis B vaccine is considered safe during pregnancy with no adverse reactions reported in the literature. Women who test negative for HBsAg and are at risk of acquiring HBV infection should be immunized during pregnancy. Proof of absent immunity (defined as absence of the antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAb-negative]) is not required before vaccination. Women considered to be at greatest risk are those with multiple sexual partners (more than two in the last 6 months), those who have been evaluated or treated for sexually transmitted diseases, recent or current injecting drug users, and those who have an HBsAg-positive sexual partner.

Although several individuals infected with HBV will test negative for the HBsAg, the virus is detectable in the blood and therefore DNA testing will show positive results. These individuals have a very low viral load and are called occult infected . The prevalence of occult HBV infection in the pregnant population and its contribution to childhood HBV infection are unknown. Case reports have suggested that occult HBV infection in pregnancy might be a significant problem in populations with a high prevalence of HBV.

Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Program

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the IOM support the referral of all HBV-positive mothers to the state’s Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Program and to subspecialists for counseling and medical treatment. The Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Program is a state-run, CDC-funded program with the goal of implementing current perinatal immunoprophylaxis recommendations throughout the United States. Pregnant women infected with HBV are identified early in pregnancy through prenatal testing and referred to case managers in the Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Program. Case managers provide counseling and encourage appropriate testing and vaccination of household contacts. They also coordinate appropriate vaccination and testing of the infant and medical treatment for the mother during pregnancy and postpartum.

Infant Immunoprophylaxis

Current CDC guidelines stipulate that infants of women who are HBsAg-positive or whose status is unknown at delivery should receive both hepatitis B hyperimmune gamma globulin (HBIG) and hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours of birth, preferably in the delivery room. This initial vaccine administration should be followed by at least two more injections of hepatitis B vaccine within the first 6 months of life. After completion of the vaccine series, testing for the antibody against HBsAg (anti-HBsAb) and for HBsAg should be performed at 9 to 18 months of age. HBsAg-negative infants with HBsAb levels greater than 10 mIU/mL are considered protected and no further medical management is required. Those with HBsAb levels less than 10 mIU/mL are not protected and should be revaccinated with a second three-dose series followed by retesting 1 to 2 months after the final dose. Passive immunoprophylaxis with HBIG at birth followed by at least 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine provides approximately 95% protection from perinatal infection, whereas the vaccine alone is approximately 75% protective.

Report Card

Although immunoprophylaxis guidelines are important for decreasing the transmission of perinatal HBV, they must be endorsed properly. A study conducted in 2006 reviewed infant and maternal records in a representative sample of 242 delivery hospitals in the 50 states, Washington DC, and Puerto Rico. The records of 4762 mothers and 4786 infants were reviewed. Among infants born to the 18 HBsAg-positive women with documented prenatal test results, 62.1% received both hepatitis B vaccine and HBIG within 12 hours. However, 13.7% were unvaccinated and 19.7% did not receive HBIG before discharge. Among infants born to the 320 women with unknown HBsAg status, only 52.4% were vaccinated within 12 hours of birth and 20.1% were unvaccinated before discharge. These findings indicate significant inconsistency in hospital policies and practices to achieve prevention of vertical transmission of HBV.

Vertical transmission

The risk of perinatal infection for infants born to HBeAg-positive mothers in the absence of prophylaxis is as high as 70% to 90% by the age of 6 months; and approximately 90% of these children will remain chronically infected. HBeAg-negative mothers carry a 10% to 40% transmission risk, and 40% to 70% of infants who become infected remain chronically infected. The likelihood of acquiring HBV infection through vertical transmission is probably linked to the viral replication status of the mother rather than to e-antigen status. E-antigen–negative mothers with a high viral load are at great risk for transmitting the virus to their infant.

Active and passive postexposure prophylaxis of the newborn with HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine is known to be safe and effective and dramatically reduces the risk of HBV transmission. This strategy has been acknowledged as the most effective intervention to contain HBV infection. Unfortunately, administration of HBIG is costly and not all countries have the resources to support this intervention, resulting in a wide variety of immunization protocols around the world.

Mode of Transmission From Mother to Infant

The vertical transmission of HBV from mother to infant occurs in the perinatal period. During delivery, maternal secretions in the birth canal come in contact with the infant’s mucosal membranes. In the immediate postpartum period, transmission results from close contact between mother and baby. Of infants born to HBeAg-positive mothers who are uninfected at birth, 34% will acquire the infection in the next 6 months. A small number of infants will be infected in utero. In a study performed in the Republic of China, 3.7% of babies tested HBsAg-positive at birth from in utero infection. Zhang and colleagues showed the ability of the virus to translocate through the placenta from the mother to the fetal trophoblast. This finding suggests a direct transplacental route of infection. Factors that cause transplacental infection remain unknown, but high maternal viral load and preterm labor are predisposing factors.

Special Circumstances

Breastfeeding is not contraindicated for HBV-positive mothers. Several studies found no difference in rates of infection between breast fed and formula fed babies. The American Academy of Pediatrics supports breastfeeding as long as the infant has received HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine as recommended.

Experts consider amniocentesis to be relatively safe. Current data, however, are limited to few observations. Given the small number of cases reported, it should be performed only if absolutely necessary.

Assisted reproduction can be safely achieved for discordant couples in which one partner is HBV-infected and the other is not. Sperm preparation techniques greatly decrease the viral load, minimizing the chances of cross-infection.

Immunoprophylaxis Failure

Despite enormous strides in preventing perinatal HBV infection, vertical transmission remains a significant route of virus acquisition worldwide. Recent statistics show that only 36% of all newborns received the HBV vaccine at birth in the 87 countries in which chronic HBV is endemic (affecting ≥8% of the total population). The lack of a universal and consistent global policy to prevent vertical transmission, and barriers to the implementation of an immunization protocol in the poorest countries, account for most infected infants worldwide.

Even in countries in which proper immunization is practiced, as many as 9% of infants whose mothers are HBsAg-positive will become infected with HBV. Another 1% to 2% of properly vaccinated infants are unable to develop sufficient amounts of HBsAb to afford long-lasting immunity. Although immunoprophylaxis failure is known to exist, the magnitude of the problem is difficult to estimate. The rate of reported immunization failure varies greatly among countries because of different immunization schedules, modes of vaccine delivery, and compliance with completing the vaccination series.

Asian countries such as China and Korea have reported immunoprophylaxis failure as high as 25% in HBeAg-positive mothers, and in 10% to 20% of all infants born to HBV-infected mothers. More recent Chinese data reported a much lower rate. In a Canadian retrospective review of data from pregnant women, 1485 HBV-positive women were identified, with an immunization failure rate of 2.1%. In an Australian study, 2% of all HBsAg-positive mothers gave birth to children who were HBV-positive. Given the variability of practices during delivery and prophylaxis protocols around the world, data obtained in foreign countries should be interpreted with caution.

Current data on immunization failure in the United States is lacking because not all infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers have the mandatory testing at 9 months of age. A study by Andre and Zuckerman reported that vertical transmission despite immunoprophylaxis (true immunization failure) is estimated to be approximately 5%. The CDC estimated that in the United States in 2007, 800 infants were infected perinatally (John Ward, MD, personal communication, 2010). Elimination of vertical transmission was identified as one of the strategic goals by the IOM in an effort to eliminate HBV infection. Determining the rate of true immunization failure in the United States is the first step toward achieving this goal. The effectiveness of the more stringent immunization protocol suggested by the IOM in 2010 must be evaluated before additional interventions are formulated.

Causes of Immunoprophylaxis Failure

Examination of the causes of vertical transmission should help identify the causes of immunoprophylaxis failure. Failure to identify infected mothers and inadequate newborn prophylaxis contribute significantly to vertical transmission. In the Australian study discussed previously, of the four children (2%) infected vertically, one was improperly immunized. Delay of the second dose of vaccine may also contribute to the rate of immunoprophylaxis failure. Only documented peripartum transmission despite adherence to an adequate immunization protocol should be considered true immunization failure. Because this is a rare event, establishing the risk factors associated with immunization failure would help identify populations to target for intervention.

True immunoprophylaxis failure has been linked to high maternal viral load. The viral load range of concern has not been defined because viral load can change over several logs during pregnancy and HBV DNA is not routinely tested during pregnancy in the United States.

Available data suggest that the measure of HBV DNA associated with immunization failure is approximately 10 8 copies/mL. The recent study in Australia examined 313 HBsAg-positive pregnant women from 2002 to 2008, and found that 47 were HBeAg-positive and had HBV DNA viral loads greater than 10 8 copies/mL. Subsequent testing showed that 4 of the 47 infants born were HBsAg-positive and HBsAb-negative. All 4 infants received the HBV vaccination series, and 3 of these received HBIG at birth. No perinatal transmission of HBV occurred in any newborns of mothers with viral loads less than 10 8 copies/mL. Thus, this study suggests that HBeAg positivity and high maternal viral load correlate with perinatal transmission. Transplacental infection might also play an important role in the transmission of HBV.

Polymorphism of maternal cytokine involved in the immune response to HBV, particularly tumor necrosis factor, interferon-γ, or interleukin-10, has also been linked to immunization failure. This polymorphism may also correlate with other factors, including intrauterine infection and high viremia. Other risk factors related to pregnancy outcome, such as preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and a complicated delivery, need further study. Cesarean section does not seem to protect against vertical transmission and immunization failure, although data are still controversial.

Minimizing the Immunization Failure

Programs encouraging proper immunoprophylaxis remain the most effective way to reduce vertical transmission worldwide. Countries such as China, where vertical transmission contributes significantly to the overall burden of disease, have implemented several strategies. For example, despite the lack of evidence that these strategies reduce vertical transmission, the rate of caesarian section and bottle feeding among HBsAg-positive Chinese mothers is 95%.

One approach to prevent perinatal HBV transmission is maternal administration of HBIG during pregnancy; several studies show varying results. Different doses and routes of HBIG were administered with different outcomes used to determine neonatal infection, including HBV DNA in cord blood or HBsAg present in infants at 6 months of age. Three of the four studies documented a beneficial effect of HIBG, whereas one study reported no obvious difference. One study examined the effect of maternal HBIG treatment on newborn vaccination and found that maternal HBIG treatment was associated with higher HBsAb rates than in infants of both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative women not treated with HBIG.

Antiretroviral therapy and vertical transmission

Because the risk of vertical transmission despite immunoprophylaxis is higher for mothers with high viremia, a sensible strategy to interrupt perinatal infection is to reduce the mother’s viral load with antiretroviral drugs before delivery. Antiretroviral nucleo(t)side analogs are a category of drug with direct antiviral action. They are used extensively to treat HBV- and HIV-infected individuals. In HIV-infected pregnant women, administration of nucleo(t)side analog therapy helped reduce the perinatal HIV transmission rate from 25% to 30% to less than 2%.

Chinese physicians have published several reports of successful use of lamivudine in the third trimester for the sole purpose of interrupting vertical transmission of HBV. Based on these reports, some experts advocate for this strategy and suggest antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all pregnant women with high HBV viremia in the United States. However, this practice remains controversial; the need and efficacy of ART to prevent immunization failure in the American population have not been proven. Studies available to support the use of ART in pregnancy are few and their scientific merit is questionable. To date, only one randomized trial and one case series have been published in the western literature.

A meta-analysis summarizing trials published in foreign languages is also available, but the studies included are of poor quality. The first report was published in 2003 from a European group in which eight pregnant women who were highly viremic (1.2 × 10 9 copies/mL) were treated with 150 mg of lamivudine daily from gestational week 34 until delivery. The infants received both active and passive immunization at birth. Within 6 to 40 days, the HBV DNA levels declined at least 1 log in five of the eight women. Although four of the infants were HBsAg-positive at birth, all but one were negative by 12 months of age (12.5%). The rate of HBV infection in a group of 24 historical controls was 28%. Xu and colleagues published the first randomized trial in 2009, enrolling 115 women who were HBsAg-positive with high viral loads; 59 women were controls and 56 were treated with 100 mg of lamivudine beginning in the third trimester and until 4 weeks postpartum. Despite a 50% decrease in vertical transmission in the treated group, these data were invalid given the high drop-out rate in the control group.

More recently, a randomized controlled trial with telbivudine was presented at the 2010 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) meeting in Boston, Massachusetts. In this trial, 190 Asian mothers with high viral loads were recruited in an open-label prospective study. The study group received 600 mg daily of telbivudine from gestational weeks 20 to 32 through 4 weeks postpartum. The rate of vertical transmission was 2.1% in the treated group and 13.4% in the untreated women. If these data can be confirmed, this will be the first trial proving efficacy. However, other considerations must be weighed before recommending late-trimester ART, such as the effect of ART on the mother, the likelihood of flares as ART is discontinued postpartum, and the potential risks, albeit small, of generating drug resistance. Furthermore, lamivudine is no longer used as a first-line drug and newer, more efficacious agents should be considered. Thus, the AASLD 2007 consensus statement concluded that more data were needed before treatment with ART to block vertical transmission could be recommended.

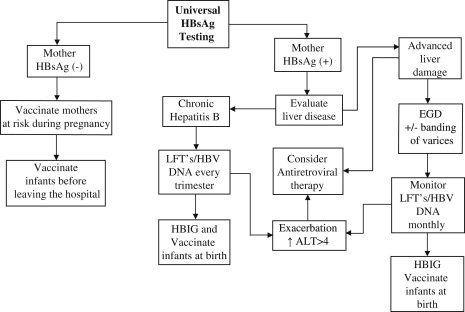

Chronic hepatitis B: assessment and monitoring during pregnancy

As a result of universal screening for HBV, pregnancy often coincides with the initial diagnosis in many HBV-infected women. Thus, pregnancy is a time of challenge for the mother, but also an opportunity to deliver appropriate medical care to thousands of infected women. The ACOG, AASLD, and CDC guidelines suggest that HBsAg-positive mothers be referred for further medical evaluation and not deferred postpartum. Although most patients will do well in pregnancy, a small percentage have significant liver disease that requires close monitoring and therapeutic intervention. Complications such as cholestasis, flare of underlying hepatitis, and hepatic failure have been described in pregnancy. In addition, more patients are becoming pregnant while on ART, which presents unique challenges. Fig. 1 presents the algorithm used to guide clinical care in the authors’ facility.