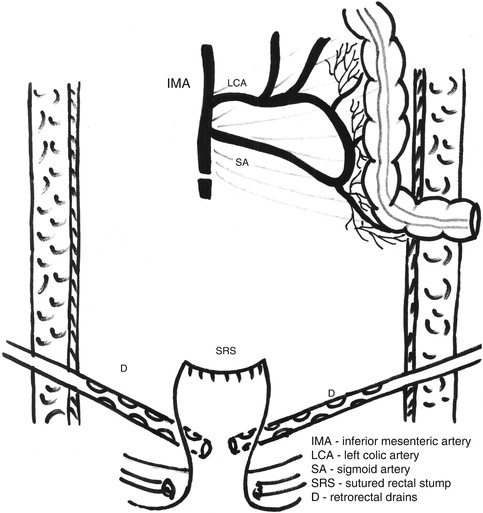

Fig. 7.1

Low ligation of the distal sigmoid artery in a clearly palliative Hartmann’s resection

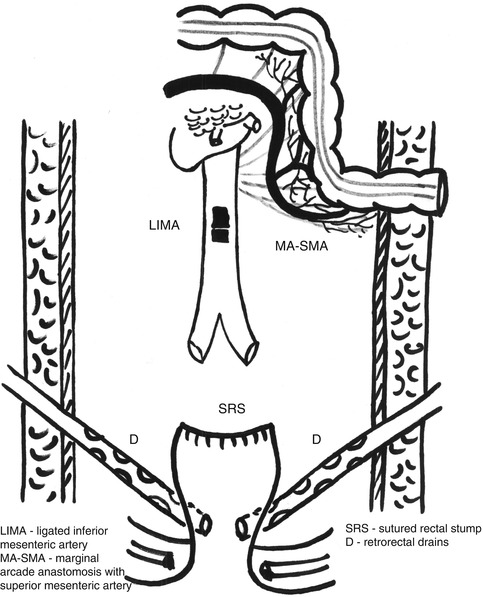

Fig. 7.2

Final aspect after a clearly palliative Hartmann’s procedure; the rectal stump is closed with sutures and two drains are placed around it

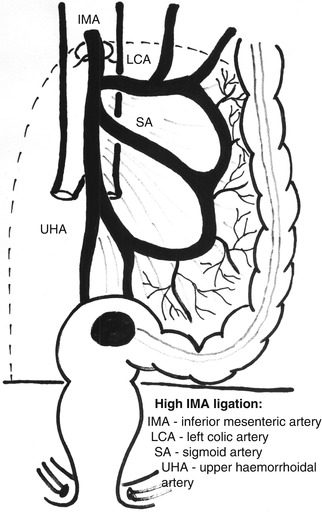

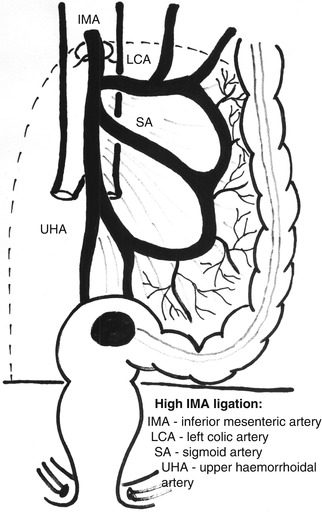

When Hartmann’s procedure is employed only because of the local condition (too altered colonic wall, peritonitis), otherwise in a patient with good condition and apparently localized rectal cancer, the resection type must be as similar as possible to the anterior resection. In these cases, ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery and vein must be done as close as possible to their origin, with or without preserving the left colic artery, but with the removal of the lymph node at this level (Figs. 7.3 and 7.4). The dilated bowel may induce difficulty at this moment, but the exteriorization of the small bowel loops from the abdomen (covered with soft, moistened drapes) and a good lateral mobilization of the sigmoid and descending colon make the individualization and sectioning of these vessels possible. Except for a very short and retracted sigmoid or its mesentery, or a previously affected sigmoid by diverticular disease, which recommend the removal of the entire sigmoid, the mobilization of the splenic flexure is not usually necessary for future stoma creation.

Fig. 7.3

The high ligation in Hartmann’s resection: inferior mesenteric artery and vein ligated and divided just below the pancreatic border

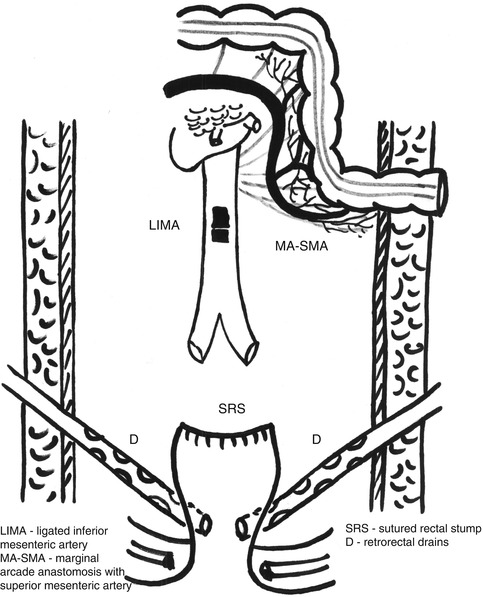

Fig. 7.4

Final aspect after a high ligation in Hartmann’s resection, also with closing of the rectal stump and pelvic drainage

From this moment, the resection of the sigmoid and rectum may be performed in the same manner as in the curative anterior resection: The colic mesentery will be divided, preserving the vascular marginal arcade along the segment which will be preserved. Different from rectal resection, dividing the sigmoid, at the level chosen for resection, is not recommended in obstructive rectal cancer due to the increased risk of stercoral spillage in the peritoneal cavity, so the rectal resection will be made with sigmoid “in situ,” which may create some difficulties in mesorectal dissection. Similar to the anterior resection, much attention must be given to preserving the upper hypogastric plexus and hypogastric nerves and especially to not entering the mesorectal fascia, with subsequent risk of residual microscopic cancer, which may compromise the oncologic result. Obviously, this is easier in upper rectal cancers, while in middle rectal cancers, dilated upper rectum will create many difficulties in doing a correct mesorectal excision. This is also an explanation for some failures after Hartmann’s resection (or extended Hartmann’s resection) in patients otherwise suitable for cure (local disease leading only to intestinal obstruction, without perforation or metastasis). Nevertheless, it has been proven that circumferential margin involvement is significantly higher after Hartmann’s resection (31.7 % of cases) than after anterior resection or Miles’ procedure; this was explained partially by the palliative and emergency character of resection [19].

When the distal point of resection is achieved, the rectum will be transected, directly or using a stapling device. Usually, conditions claiming a Hartmann’s resection do not allow a total mesorectal excision to be performed, but if cancer cure may be considered an endpoint, the total mesorectal excision must be performed in spite of all mentioned difficulties. Still, in many cases, the mesorectal dissection will stop at the level of the rectal sectioning.

If a stapling device is not available or cannot be used, the rectal stump may be closed simply with interrupted or continuous sutures or may even be left open with a drain in it (usually, when the closure is very difficult, in case of a very narrow pelvis and a very low resection). In both such cases, due to the risk of pelvic sepsis (abscess formation), pelvic lavage followed by pelvic drainage is mandatory. It is now the moment for the sigmoid sectioning and rectal specimen removal.

Colostomy Formation

There are several possibilities of performing a colostomy, all of them being related to the surgeon’s preferences. Regardless of the technical varieties, there is a series of conditions to which a colostomy must submit: good vascularization of the exteriorized bowel, with no tension, and the possibility of being easily and efficiently covered by a colostomy bag that implies a comfortable distance from the midline incision in order to avoid its contamination but also a sufficient distance from the bony structures or cutaneous folds. Every time a colostomy creation is anticipated, the stoma area must be evaluated preoperatively and marked for the ease of intraoperative completion of the above enounced conditions. In Hartmann’s resection, the surgeon must also keep in mind that usually colostomy will be a definite in most of the cases.

Usually, the stoma-creation time commences with an incision on the left side of the rectus abdominis projection area, dissection of the subcutaneous layer, and incision of the anterior sheet of the rectus abdominis. After the dissociation of the muscular fiber, an incision is made on the posterior sheet of the rectum abdominis and peritoneal sheet, and the sigmoid (or the mobilized descending colon) is exteriorized. A series of sutures are then placed around the exteriorized bowel to ensure its fixation to the tegument. In the case of good local condition, per primam maturation of the stoma might be possible, but sometimes a secondary opening of the stoma is performed 2 or 3 days later (Fig. 7.5).

Fig. 7.5

Final aspect after a Hartmann’s resection: a midline large incision with left colostomy; the exteriorized bowel will maturated 7 days after the resection

Postoperative Results

Although postoperative results of Hartmann’s resections have considerably improved over time, still an important number of cases will continue to develop postoperative complications, leading to an important morbidity and mortality after this procedure. The main cause of this situation is represented by the conditions themselves imposing a Hartmann’s resection: severely altered general status and advanced neoplastic disease at the time of surgery, emergency operation for obstructing or perforated rectal cancer, or, even worse, a reoperation for a postoperative peritonitis after failure of an anterior rectal resection.

Excluding general complications, favored especially by the patient’s existing comorbidities and stoma-related complications, Hartmann’s resection has a particular frequent type of postoperative morbidity, represented by pelvic abscess and rectal stump fistula formation. The latter has relatively little consequences in terms of gravity (except for its contribution in pelvic abscess formation), but the former represents an important cause of death of these patients.

The incidence of pelvic sepsis after a Hartmann’s resection decreases from 30 (even 75 % for extended Hartmann’s resection) to 18.6 % in the study of Tøttrup et al. The incidence of pelvic sepsis after Hartmann’s resection seems to be significantly higher in men (45 %), with low closure of the rectal stump (below 2 cm from the pelvic floor) – 32.9 % [20].

In order to reduce the incidence of pelvic sepsis after Hartmann’s resection and especially after extended Hartmann’s resection, the best method is to permit a good drainage of the rectal stump and its surroundings; therefore, a policy of non-peritonealization and a good drainage of the pelvis and presacral space are mandatory. Transanal drainage of the rectal stump may be useful in low or very low rectal resections, when the rectal stump suture line is difficult to be performed or even impossible.

Postoperative mortality after Hartmann’s resection for rectal cancer decreases significantly; still, it is impossible to disappear completely due to severe conditions imposing such type of resection. The highest mortality after Hartmann’s procedure is encountered in the study of Biondo et al., with 56.2 % of patients dying after this type of resection, but explained by the patient selection for the procedure: Only high-risk (ASA IV) patients with fecal peritonitis, renal failure, hemodynamic instability, or advanced cancer were selected for resection without anastomosis [2].

Regardless of its high morbidity and mortality, Hartmann’s resection remains a life-saving surgical procedure, which makes it difficult to believe that it will be surpassed by other therapeutic methods, at least for a specific category of rectal cancer patients: perforated tumors, advanced intestinal obstruction, and advanced locoregional or distant disease, otherwise requiring an abdominoperineal resection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree