At a practical diagnostic pathology level, the etiology of granulomas in the liver will most often not be evident by histology alone. Nonetheless, there can be clues that will help you weigh the differential from more likely to less likely, and this information can be very helpful to your clinical colleagues. Remember that simply listing a generic differential for granulomas in your surgical pathology report is not terribly helpful because that generic differential is already known to most physicians, having been mastered by them in medical school.

Different types of granulomas have distinct but overlapping differentials and they are considered in more detail in the following sections. However, some broad principles can be applied. If you follow these general guidelines, you will be comfortable handling most liver biopsies with granulomas.

A useful first step is to decide if the liver disease is primarily granulomatous or if the granulomas represent part of a larger disease injury pattern. For example, in sarcoidosis, the granulomas are often the primary disease process. In contrast, granulomas in PBC, when present, are but one component of the disease. To make this distinction, the entire biopsy has to be examined and correlated with clinical findings to see if there is evidence for a disease process beyond that of the granulomas. The overall location of the granulomas, whether they are in the portal tracts, lobules, or both, generally does not provide a strong clue to the etiology. One exception is granulomas associated with a florid duct lesion, which would strongly suggest either PBC or a drug effect.

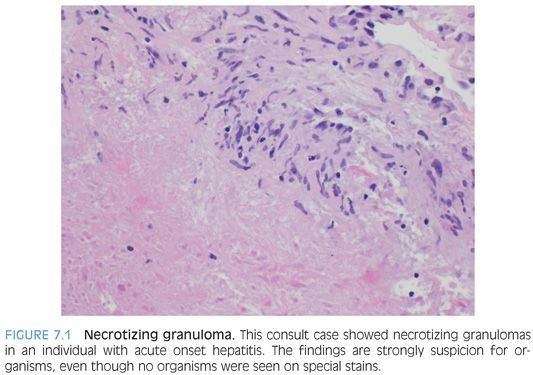

Second, granulomas that have central necrosis are most likely infectious (Fig. 7.1). Look carefully for organisms such as schistosomiasis and do fungal stain and an acid-fast stain on all cases of necrotizing granulomas. You should do a fungal and acid-fast bacillus (AFB) stain even if you see parasitic organisms in some of the granulomas on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) because multiple infections can coexist. In some cases, it can be helpful to do a second set of AFB and Gomori methenamine-silver (GMS) stains on deeper cut sections. In many cases with necrotizing granulomas, you will still not have a definitive diagnosis after organism stains, but your report should still convey that the granulomas are suspicious for infection. Rarely, large granulomas from other diseases such as sarcoid can also have central necrosis. In these cases, the necrosis is typically fibrinoid and is without the “dirty” nuclear and cellular debris seen in many infectious necrotizing granulomas.

As a third general principle, granulomatous disease that contains primarily portal-based granulomas of varying ages—including older fibrotic granulomas as well as plump, fresh epithelioid granulomas—is a pattern most commonly seen with sarcoidosis.

Fourth, granulomatous biliary tract disease is most likely to be PBC or a drug effect. Sarcoidosis should also be considered. A subset of cases of sarcoidosis can involve hilar lymph nodes, and the nodes can become sufficiently enlarged and fibrotic that they cause chronic biliary obstruction. Such cases can have obstructive type biliary tract changes, but the granulomas typically do not directly involve the bile ducts. Parasitic infections of the biliary tree can also cause granulomatous biliary tract disease but are rarely encountered on percutaneous liver biopsy.

Fifth, granulomatous diseases associated with a moderate or marked lobular hepatitis are usually drug reactions. The potential list of drugs that can cause granulomas is huge and ever growing, and there is little point in trying to memorize them. It is better for patient care to look up the medications that are being used by a patient with a granulomatous drug reaction in an actively maintained database—online sources are probably the best. Nonetheless, there are some drugs that are well known for causing granulomatous hepatitis, and it can be useful to have a few of these tucked away in your memory: allopurinol, hydralazine, isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, and phenytoin.

Sixth, granulomatous disease presenting as acute onset hepatitis is almost always infectious or drug effect–related. If the acute onset hepatitis is associated with a febrile illness, this further strongly favors an infection or drug-induced hepatitis.

Seventh, epithelioid granulomas should be polarized—the H&E findings alone can sometimes indicate the presence of foreign material, but in other cases, the correct diagnosis is only achieved after polarization. Although you will polarize a whole lot of granulomas before you find a positive one, it is still an important part of the workup.

Finally, a note about terminology. The term granulomatous hepatitis is best reserved for cases in which granulomas are thought to be a key element of the liver injury. Examples include drug reactions, infections, and sarcoidosis. In contrast, small idiopathic granulomas are also seen in the setting of other chronic liver disease, such as chronic hepatitis C or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Referring to these latter cases as granulomatous hepatitis may be technically correct but can lead to significant clinical confusion. A better approach is often to diagnose the chronic liver disease (such as chronic viral hepatitis or NAFLD) in the usual way and then mention that as an additional finding, there are small incidental epithelioid granulomas.

Specific Types of Granulomas and Their Disease Correlates

CASEATING GRANULOMAS. Caseating granulomas have central necrosis. The necrosis is “dirty,” with nuclear debris and dead cellular material. Caseating granulomas are almost always infectious in origin. Caseation typically involves a reasonable-sized area, and tiny areas, of a few cells in size, with equivocal fibrinoid necrosis due to increased eosinophilia are not truly caseating in most cases. In fact, many of the reports of caseating granulomas from noninfectious causes fall into this category of tiny foci of equivocal fibrinoid-type necrosis, which probably does not represent true caseation. It is generally accepted that caseating granulomas can be seen with sarcoidosis, but this finding is very rare and should be approached with caution to make sure the granulomas are not infectious. Sarcoidal granulomas with necrosis tend to be very large and are extremely rarely sampled on liver biopsy. Sarcoidosis in liver biopsies essentially never has caseating necrosis of small- or medium-sized granulomas. Sarcoidal granulomas sufficiently large to become necrotic are more common in lymph nodes or the lung.

EPITHELIOID GRANULOMAS. Epithelioid granulomas are one the most common granulomas encountered in liver pathology. These granulomas are defined by an aggregate of histiocytes that have sharp borders separating them from the surrounding tissue. They are typically amphophilic to slightly eosinophilic in appearance and range considerably in size. Admixed lymphocytes are common. Epithelioid granulomas can be seen in almost all forms of primary and secondary granulomatous liver disease. They should be fully worked up with organism stains, correlated with additional liver biopsy findings, and correlated with available clinical and laboratory findings.

FIBRIN RING GRANULOMAS. Fibrin ring granulomas are composed of a central fat droplet surrounded by an eosinophilic ring of varying thickness and an outer layer of macrophages. They were first described in Q fever but can be seen in a wide range of infectious conditions (Table 7.2). Other findings in the rest of the biopsy can give you some clues to the possible etiology, but in many cases, the etiology is determined by serologic or other laboratory testing. They are most commonly associated with infection or drug effect and that should be conveyed in the pathology report, even if an etiology is not clear at the time the pathology report is released.

FLORID DUCT LESIONS AND GRANULOMATOUS INFLAMMATION. A florid duct lesion is a medium-sized bile duct that is cuffed and infiltrated by lymphocytes. The duct epithelium is injured, often appearing disheveled, and has reactive changes. In some cases, the florid duct lesion can be associated with numerous macrophages that form ill-defined aggregates in the portal tracts. This finding is often called granulomatous. In rare cases, well-formed epithelioid granulomas can be seen associated with florid duct lesions, but in general, well-formed epithelioid granulomas are more common in the lobules in PBC. The differential for florid duct lesions is essentially PBC (large majority of cases) versus a drug effect.

FOREIGN BODY GRANULOMAS. Foreign body granulomas (FBGs) in the liver can result from many different causes. Talc granulomas from injection drug use are widely used as an example, although they are not as commonly seen in practice today. Other potential causes include prior abdominal surgery or interventional radiology procedures such as tumor embolization. In some cases, the cause is not clear from the available history. The diagnosis is made by either seeing the foreign material on H&E stain or by polarization of the granuloma and identifying birefringent material. Exposure to heavy metal, such as beryllium, can also lead to granulomas, although granulomas are more commonly found in the lungs or skin than in the liver.

GRANULOMATOUS INFLAMMATION. This term is used to describe histiocyte-rich inflammation, where the histiocyte aggregates do not form well-defined granulomas. This pattern can be seen in a wide range of conditions but overall is most commonly seen in the portal tracts in association with either drug effects or biliary tract disease. Lobular granulomatous inflammation is most likely to be a drug effect or infectious. Finally, granulomatous inflammation can also be seen when the wall of an abscess has been biopsied.

LIPOGRANULOMAS. Lipogranulomas are commonly encountered in surgical pathology. Lipid granulomas are composed of small clusters of macrophages with small droplets of fat/lipid within them (eFig. 7.1). They are most commonly seen in chronic hepatitis C or in fatty liver disease but can also be seen in any other different liver diseases. Lipid granulomas may be associated with focal fibrosis but by themselves do not affect fibrosis progression in chronic liver disease. They classically have been associated with mineral oil, a commonly used food additive. However, in some cases, especially with obesity, it is possible that they may also be lipid-associated.

MICROGRANULOMA. Microgranulomas are defined as small collections of Kupffer cells (typically three or four) in the hepatic lobules. There should be no necrosis or polarizable material. Microgranulomas are a reparative process in response to an episode of lobular hepatitis and are most common in the setting of a single acute episode of hepatitis that has substantially resolved by the time of biopsy, leaving only the microgranulomas as testament to the prior injury. This finding is an important pattern to recognize, but the term microgranulomas can be misunderstood by clinical colleagues, so is probably best avoided in diagnostic reports. The microgranulomas are typically periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)–positive, in contrast to epithelioid granulomas that are PAS-negative.

GRANULOMAS ASSOCIATED WITH INFECTIONS

Granulomas can be seen with bacterial infections, viral infections, fungal infections, and parasites. For the most part, there are no specific histologic findings that will allow confident diagnosis for the cause of the granulomas on H&E stains, with the exception of finding parasitic organisms. For this reason, organism stains are critical tools for evaluating granulomas. Specific infections are discussed in the following sections, but two important points should be kept in mind. First, infections rarely “read the book” and there is substantial overall for the histologic findings between different infectious organisms. Second, evaluating granulomatous hepatitis is often challenging but doubly so if clinical findings are not incorporated into the histologic evaluation.

BARTONELLA HENSELAE. Bartonella henselae is the most common cause of cat scratch disease. In most cases, there is a skin inoculation followed by infection of lymph nodes that drain that area of the skin. However, very small subsets of individuals develop disseminated disease that can involve the liver. Affected individuals typically are not obviously immunosuppressed and present with systemic findings of fever, weight loss, and malaise. Liver lesions are frequently multiple and can resemble tumors on imaging studies. The hilar lymph nodes are also commonly enlarged. Biopsies, when they read the book, show irregular geographic areas of neutrophilic inflammation admixed with fibrinoinflammatory debris surrounded by an inner layer of histiocytes and a second outer layer of lymphocytes. In the most perfect cases, the histiocytes will show a somewhat vague nuclear alignment or “palisading.” These granulomatous areas can also be further surrounded by a thick fibrous rim. Immunostains for organisms (Warthin-Starry or Steiner) can be very helpful. Organisms are usually (or at least most confidently) identified in small clumps but also can be found as single organisms. Areas of necrosis are usually the best hunting ground to find the organisms. However, special stains will be negative in many cases, and the diagnosis is made by serologic studies. B. henselae can also cause peliosis hepatis. Finally, silver stains can have a lot of background, so it can be very helpful to have a positive control to double-check the morphology before you evaluate the stains.

BRUCELLA. Brucella is named after Sir David Bruce, who isolated the organism from British soldiers who died from “Malta fever.” Brucella infection is relatively rare and most commonly seen in individuals working with livestock. There is generally a 2- to 4-week latency period. Infection is transmitted to humans usually by aerosol from infected animals. Human-to-human transmission is very rare. Infection, however, can also occur after ingesting undercooked contaminated foods or unpasteurized milk or cheese. Laboratory infection can also occur and should be considered in laboratory workers who develop unexplained infection-type symptoms.

Affected individuals generally present with infection-type symptoms including fevers and malaise. The fevers are typically acute in onset but can wax and wane in intensity. Headaches and arthralgia are also common. Hepatomegaly and lymphadenopathy are commonly found on physical exam. Liver biopsies range in their findings from nonspecific inflammatory changes to granulomatous hepatitis. The granulomas are noncaseating and can range all the way from poorly formed granulomas to discrete, well-formed epithelioid granulomas. Brucella is a gram-negative coccobacilli, but organisms are generally not seen on special stains.

LISTERIA MONOCYTOGENES. Listeriosis affects neonates and the elderly most commonly, with pregnant women also at risk and making up 30% of all cases. In neonates, the organism can cause sepsis and meningitis. Children and adults who are immunocompromised are also at increased risk. The genus Listeria is named in honor of Sir Joseph Lister, a British surgeon who pioneered early antiseptic methods in surgery, using phenol to sterilize surgical instruments and to clean wounds. The mouthwash Listerine is also named in his honor. Interestingly, Lister’s father made important contributions to the development of microscopes.

Listeria monocytogenes is often a food-borne pathogen, and although relatively rare, an estimated 20% to 30% of clinical infections lead to death. The organism can grow at 0°C and is considerably resistant to freeze and thaw cycles as well as heat. Contaminated foods can include unpasteurized milk, cheese (particularly soft cheese), raw vegetables, and raw and smoked meats. A large outbreak in the United States in 2011 was associated with cantaloupes.

The primary site of infection is the small intestine. The histologic findings with hepatic involvement vary, but typically, there are scattered microabscesses as well as small granulomas. Occasionally, larger epithelioid granulomas can be found. The organism is a short pleomorphic gram-positive rod, but organisms are typically sparse and hard to find on special stains.

MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) was first identified in 1882 by Robert Koch (whose Koch’s postulates laid the foundation for modern microbiology). The infection is spread by aerosolization, usually by cough or sneezing. The organism primarily causes respiratory tract disease, but in a subset of individuals, the liver is also affected. If the pulmonary vein becomes eroded and organisms directly access the pulmonary veins, military tuberculosis can develop.

In one autopsy study, granulomas were found in the liver of approximately 40% of individuals with MTB. The granulomas were caseating in 60% of cases, noncaseating in 25% of cases, and “atypical” in 15% of cases.1 In 20% of cases, there was secondary biliary tract disease because of bile duct compression due to enlarged granulomatous hilar lymph nodes. In MTB cases without granulomas, the liver biopsies were more likely to show fatty change and nonspecific chronic inflammation. Fibrosis was relatively uncommon, being found in 15% of the total number of cases, with 7% of the livers showing bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis.1 Of note, biopsy-based studies typically find a lower rate of granulomatous disease than autopsy-based studies.

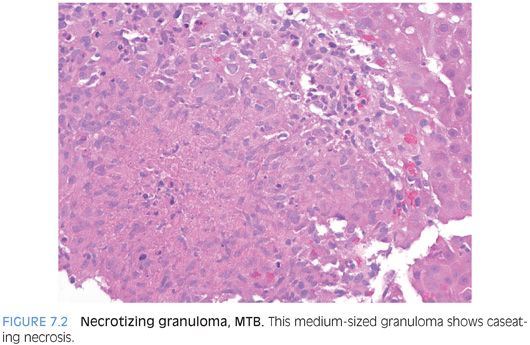

The MTB granulomas with caseating necrosis are typically small to medium in size (Fig. 7.2). The organisms are identified on AFB stains as small red rods, usually with very few organisms seen (eFig. 7.2). Because the organisms are sparse, a repeat AFB stain on deeper level can sometimes be helpful. Other clinical and laboratory findings can help arrive at a diagnosis in those cases where organisms are not seen. Tuberculomas or pseudotumors have also been reported.2 Histologically, tuberculomas show extensive central caseating necrosis, often with a rim of giant cells as well as fibrosis.