11. GASTROINTESTINAL PATHOLOGY

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

1. Provide an overview of gastrointestinal disease.

2. Give an insight into the relative clinical importance, in terms of incidence and clinical import, of the different disorders.

3. Explain the features of the more common disorders in terms of disruption of the normal function.

Introduction

Understanding normal body function is the foundation of clinical practice. In this book the normal anatomy, physiology and histopathology of the gastrointestinal tract has been applied to explain why different clinical conditions manifest their specific signs and symptoms. In the first 10 chapters, clinical examples of diseases have been selected to highlight specific aspects of physiological gastrointestinal function. The final chapter provides an overview of gastrointestinal pathology and its manifestations.

The diseases described in this chapter are addressed anatomically under the headings: the oral cavity, the oesophagus, the stomach, the duodenum, the pancreas, the liver and biliary tract, the small bowel and the large bowel. In addition to these sections, three other clinical areas are addressed separately. These are:

1. Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract, which is the commonest cause of death from digestive tract disorders.

2. Abdominal pain, which is one of the most frequent causes of acute presentation to the health service.

3. Gastrointestinal surgery, which provides further insight into the functional importance of the components of the digestive tract.

Gastrointestinal malignancy

In the Western world, malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract accounts for approximately 10% of all deaths and 40% of deaths from cancer. Effective and even curative treatment is available for these tumours if they are diagnosed at an early stage. For these reasons, malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract must be considered at an early stage in the diagnostic process for any patient presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms (Table 11.1).

| Some 40% of all deaths from cancer in the Western world are attributable to gastrointestinal malignancy. Most early symptoms are due to the abnormal function of the organ. | ||

| Site | Cases per annum (England and Wales) | Presenting symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Large bowel | 35 000 | Alteration in bowel action |

| Stomach | 10 000 | Indigestion, epigastric pain |

| Pancreas | 10 000 | Jaundice, back pain, steatorrhoea |

| Oesophagus | 8000 | Regurgitation, difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia) |

| Liver (hepatoma) | 500 | Features of chronic liver disease. A history of alcohol abuse or hepatitis |

A number of general factors will influence the clinician as to the likelihood of any symptom being due to an underlying malignancy:

• The age of the patient

• The duration of symptoms

• The progression of symptoms

• Identifiable aetiological factors

• A family history of malignancy.

Solid tumours, including gastrointestinal cancers, occur in patients with increasing frequency with advancing years. They are rarely diagnosed in patients under the age of 50 years, but thereafter rapidly increase in frequency into the seventh decade of life. Symptoms may start in an insidious fashion, but often progress over a period of weeks or months. This is in contrast to acute infection, which often has a sudden onset of symptoms, or chronic inflammatory conditions, which commonly display periods of exacerbation and remission.

Environmental factors may also alert the clinician to the underlying diagnosis. Thus, a history of prolonged alcohol intake and chronic liver disease can alert the clinician to the possibility of a primary liver tumour (hepatoma).

The importance of dietary intake in causing gastrointestinal malignancies has long been recognized. In the Indian subcontinent chewing beetle nut is known to predispose to oral cancer, ingestion of pickles and salted fish in Japan is associated with an increased incidence of gastric cancer, and the high animal fat, low roughage diet of the Western world predisposes to colorectal cancer. More recently it has been recognized that many gastrointestinal malignancies develop because of an underlying inherited genetic predisposition.

Genetic predisposition may influence up to one-third of all colorectal cancer. In patients who are already predisposed to an inherited colorectal tumour, the tumours will tend to occur at an earlier age than in the general population. In addition, the tumours may be multiple because the predisposition affects all the cells in the large bowel mucosa. A clinical history from the patient may reveal first-degree relatives affected by the same tumour, because they are usually inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. The genetic defects that have led to the predisposition pertain to fundamental cellular functions. It is usual for these patients to be at risk of developing more then one type of tumour, and so a history of several different tumours in the same patient would also lead to the suspicion of an underlying inherited predisposition.

The most common tumours of the gastrointestinal tract affect its mucosal lining. These cells are presumed to be most at risk because of their high rate of proliferation. Moreover, these cells are constantly subjected to injury by ingested carcinogens. By comparison, tumours of the muscle wall, connective tissue, lymphatics or serosal surface of the bowel (peritoneum) are rare. The vast majority of gastrointestinal tumours are tumours of the glandular structures (adenocarcinomas), that develop from the glandular cells of the mucosal lining of the gastrointestinal tract. In the clinical setting, if a metastatic tumour deposit is identified, histological features of an adenocarcinoma would alert the clinician to look for a primary tumour in the digestive tract.

Symptoms of gastrointestinal malignancy

It is helpful to categorize symptoms of malignant disease into three groups:

• Symptoms due to primary disease

• Symptoms due to secondary disease

• Symptoms due to non-metastatic manifestations of malignancy.

Primary disease

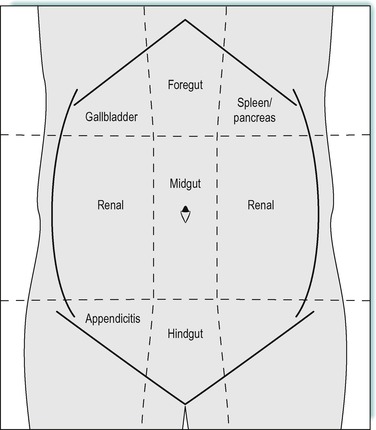

The symptoms of malignant disease of the gastrointestinal tract will depend upon the site and function of the part of the gastrointestinal tract that is affected. Carcinoma of the oesophagus will usually present with difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia), whereas adenocarcinoma of the colon will usually manifest with symptoms of a change of bowel habit. In addition to symptoms of disordered function, the site of the pain may also help to localize the tumour. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma often presents with back pain because of the retroperineal position of the pancreas, where a tumour of the liver may be associated with pain in the right side of the upper abdomen because of a localized inflammatory response in the overlying peritoneum (Fig. 11.1).

Secondary disease

One of the features of malignancy is the ability of the tumour to spread from the site of primary disease. This spread may occur via the lymphatics, the bloodstream or through the peritoneal cavity (transcoelomic spread). The lymphatic drainage follows its arterial blood supply. Consequently, tumours of the stomach, small bowel or large bowel can spread via the lymphatics to the root of the coeliac artery, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery respectively. As these lymph nodes are deep inside the abdominal cavity such spread is often initially undetected. The tumour may spread further up the thoracic chain and manifest as a swelling in the supraclavicular lymph nodes in the neck. Because the thoracic duct drains into the veins on the left side of the neck, an enlarged lymph node in the left supraclavicular region is always suspicious of lymphatic spread from an underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.

The venous drainage from the gastrointestinal tract is via the portal vein to the liver. For this reason gastrointestinal malignancies commonly develop blood-borne metastases in the liver. Abdominal examination may reveal enlargement of the liver in the right sub-costal region and affected individuals may occasionally present with symptoms of pain or jaundice.

Non-metastatic manifestations of malignancy

Malignancy, particularly in its advanced stages, is associated with an increased metabolic rate. This is due in part to the rapid cell division and tumour growth, and also due to secreted proteins released from the tumour. This catabolic state results in loss of body weight and, in its advanced stages, visible loss of muscle mass. This can occur in the presence of a normal dietary intake, and is one of the most common non-metastatic manifestations of malignancy. A further common finding is anaemia, due to bone marrow suppression. Because gastrointestinal malignancies usually disrupt the epithelial lining, which protects the gastrointestinal tract from injury, blood loss from the gastrointestinal tract is also common. The blood loss may be chronic and is often not clinically apparent. As the iron stores are depleted, red blood corpuscle maturation becomes impaired. An iron-deficient anaemia develops, in which the red blood cells are smaller (microcytic) and contain a reduced haem component (hypochromic).

Colon cancer

A 60-year-old woman presented to her general practitioner (GP) because of gastrointestinal symptoms. On direct questioning she said that the frequency of her bowel action had increased over the preceding weeks. In addition she had noticed some traces of blood in her stool on two occasions. She also complained that the consistency of her stool had changed and that she had not passed a formed stool in the preceding 6 weeks. No other person in the family had suffered any recent gastrointestinal upset and she had not suffered similar symptoms in the past. On specific questioning, she informed her GP that her father had died from colorectal cancer.

On examination, the GP found the patient to be anaemic, and her clothes were loose, indicating she had recently lost weight. Examination of her abdomen revealed an enlarged liver.

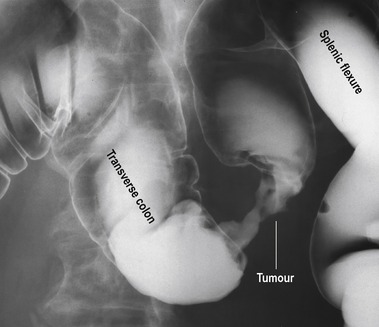

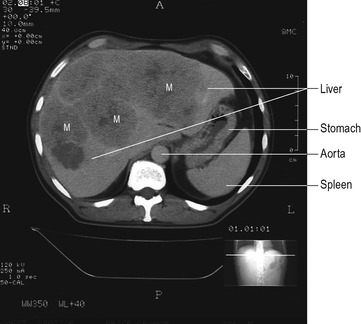

The GP was concerned that she may have an underlying colonic cancer and referred her to the hospital for further investigation. The consultant arranged a barium enema and a CT (computerized tomography) scan of her liver. The barium enema revealed a narrowing in the colon consistent with a carcinoma. The CT scan of the liver revealed a single metastasis in the right lobe. The diagnosis was explained to the patient and arrangements were made for surgery. At operation a left hemicolectomy was performed. This involved removal of the sigmoid and descending colon with its blood supply, and subsequent anastomosis of the splenic flexure to the recto-sigmoid junction. In addition, the right lobe of the liver, containing the metastasis, was removed.

Following operation, the patient made a slow but steady recovery. She returned to a normal diet on the 6th postoperative day. She did not become jaundiced following her operation.

Common gastrointestinal malignancies

In the Western world over half of deaths are accounted for by diseases of the cardiovascular system. The next most frequent cause of death is that of malignancy, which accounts for approximately 40% of all deaths. Gastrointestinal malignancies account for over 30% of all deaths from cancer, some 60 000 deaths per annum in England and Wales alone. Unfortunately, although early tumours can often be cured by surgery, most patients present after the disease has spread and as a consequence, treatment is less likely to be curable. The reserves of function in the gastrointestinal tract are such that radical resection of large sections is still compatible with a full and active life.

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

Carcinoma of the oesophagus affects approximately 5/100 000 of the population per annum. Two-thirds of the tumours are squamous carcinomas and the rest are adenocarcinomas. This reflects the epithelial lining of the oesophagus, which is of squamous type. Adenocarcinomas are usually localized to the distal third of the oesophagus and probably develop from ectopic gastric mucosa.

The classical symptom is of difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia). The symptoms are slowly progressive, with patients describing difficulty in swallowing solids and often having altered their diet to compensate. Oesophageal tumours may enlarge into the lumen, but more often, will infiltrate diffusely along and around the oesophageal wall (Table 11.2). The tendency for these tumours to grow along the wall of the oesophagus makes complete surgical resection difficult. Furthermore, the lack of a serosal covering to the oesophagus enables direct extension of the tumour into the mediastinum. Involvement of the adjacent trachea and bronchi will result in respiratory problems. The oesophagus and rectum are the only two parts of the gastrointestinal tract that are not covered by a peritoneal coat, and tumours in these two locations commonly invade surrounding local structures. Spread into the lymphatic system may manifest with a palpable supraclavicular lymph node, and spread into the portal venous system results in the development of liver metastases. Because tumours of the oesophagus do not usually invade the lumen of the oesophagus, dysphagia is a late feature and as a consequence the tumour is rarely curable. Only 6% of patients survive for 5 years.

| Symptom | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia) | The tumour may encase the oesophagus leading to narrowing or infiltration of the mucosal coat resulting in impaired motility |

| A history for many years of painful swallowing | It can develop following longstanding oesophagitis in the lower oesophagus |

| Weight loss | This may be due to alteration in diet secondary to difficulty in swallowing |

| Respiratory symptoms | Problems with swallowing will usually predate the development of metastatic disease. The patient may have symptoms from local infiltration of the organ such as the bronchi or trachea |

A number of aetiological factors are known to be associated with this tumour. The most frequent of these are heavy alcohol intake and smoking. These factors probably account for much of the variation in instance seen across different populations. A further interesting aetiological factor is that of acid reflux. Chronic oesophagitis associated with an incompetent gastro-oesophageal sphincter causes damage to the mucosa in the lower third of the oesophagus. This chronic injury appears to predispose to the development of adenocarcinoma in the lower third of the oesophagus. These different aetiological factors all result in a chronic injury to the oesophageal mucosa which over a period of time can lead to neoplastic change.

Treatment

Alteration in bowel habit is a common symptom of colonic cancer. It can be due to partial obstruction of the lumen of the large bowel or be the result of ulceration of the mucosal surface. Ulceration can also give rise to the symptoms of intermittent bleeding.

Colorectal cancer clusters in families in up to 20% of cases and so a family history of this disease is not uncommon in affected individuals. This is believed to be genetically determined, although the molecular basis in most families is not understood. Non-metastatic manifestations of gastrointestinal malignancies are more common in advanced disease and include weight loss and anaemia. The patient may have also been anaemic because of chronic gastrointestinal bleeding.

The GP was suspicious that the enlarged liver was due to metastatic disease, and in the light of the patient’s large bowel symptoms the GP felt that a colorectal cancer was the most likely diagnosis. A double-contrast barium enema outlines the lining of the bowel, and infiltration by neoplasm creates a rigid narrowing that is easily visualized (Fig. 11.2). Computerized tomography is a useful way of defining abnormal areas of tissue in solid organs like the liver. The increased vascularity of metastatic tumours makes these easy to visualize on a CT scan (Fig. 11.3).

Surgical treatment required removal of the primary tumour, the draining lymph nodes, and the single metastasis in the liver. Because blood-borne metastases from colonic cancer preferentially spread to the liver, resection of these advanced tumours can still be curative for selected cases. It is important to exclude other sites of metastatic disease before undertaking such a procedure. The second most common site of spread from colonic tumours is the lung, which is why the chest X-ray was reviewed prior to surgery.

Normal bowel function following segmental resection of the colon would be expected. No impairment of liver function would be anticipated following a limited resection so jaundice or fat malabsorption would not be anticipated.

Gastric carcinoma

Gastric carcinoma (Table 11.3) is exceptional, in that its incidence has been in steady decline for the last 30 years, while other gastrointestinal tumours have increased in frequency with increased longevity. Despite this, it remains the third most common cause of death from gastrointestinal tumours in Western countries, and is a major health issue in Japan and Chile. Variation in populations is believed to be due to local environmental, mainly dietary, factors. Recognized dietary factors include spiced foods, dietary nitrates, as well as smoking and alcohol. Helicobacter pylori infection, which is known to predispose to peptic ulcer disease, has also been implicated in gastric carcinomas. Conditions injurious to the gastric mucosa, such as pernicious anaemia and atrophic gastritis, are also associated with an increased incidence of subsequent neoplastic change. Symptoms due to the primary gastric tumour either arise as a consequence of ulceration of the mucosa, or from diffuse infiltration of the muscular wall. The ulcerating lesion has been classified as ‘intestinal’, whereas widespread infiltration of the muscle is classified as ‘diffuse’ type. Ulcerating tumours may present with pain from the injury to the mucosa, bleeding from erosion into underlying blood vessels, or peritonitis from perforation of the ulcer allowing gastric contents to leak into the peritoneal cavity. In contrast, diffuse gastric cancer often presents with a more insidious onset. The infiltrating nature of this tumour leads to a constricted stomach with a grossly thickened wall (lienitis plastica). The nature of diffuse-type cancer mitigates against successful surgical resection. Unfortunately many gastric cancers present at an advanced stage. Patients may have an enlarged liver and associated jaundice due to blood-borne metastases. The disease may spread through the stomach wall onto the peritoneum causing ascites. In these situations the tumour is incurable.

| Aetiology | The storage function of the stomach makes it particularly susceptible to ingested toxins and dietary factors that can contribute to malignant change |

| Symptoms | |

| Bleeding | Ulceration of the tumour results in exposure of the submucosal vessels |

| Abdominal distension | Gastric tumours often spread from the serosal surface of the stomach creating peritoneal metastases. Leakage of extracellular fluid occurs in association with these lesions and gives rise to ascites |

| Weight loss | This is more a feature of advanced disease in gastric cancer because the tumours do not usually prevent the passage of ingested food (unlike oesophageal cancer) |

Tumours of the pancreas

In common with other gastrointestinal tumours, the majority of tumours of the pancreas are adenocarcinomas developing from the exocrine component of the organ. Because of the high concentration of endocrine cells in the pancreas, they are also the commonest site for endocrine tumours and account for 15% of pancreatic neoplasms. The site of the tumour in the pancreas and the nature of the cell type involved in the tumour will determine its presenting symptoms.

Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas

A 70-year-old man presented to his GP with symptoms of vague upper abdominal pain, which he had noticed over the preceding weeks. From the clinical history, the doctor noted that the patient was a smoker. He suspected the symptoms may be due to peptic ulcer disease and prescribed a course of H2 antagonists. The patient returned after 2 weeks without resolution of his symptoms. On this occasion, the patient declared that the pain had spread to his back. The doctor considered the symptoms may be due to gallstones and arranged an ultrasound scan of the gall bladder. The ultrasound scan confirmed stones in the gall bladder, but also suggested that there was a degree of dilatation of the common bile duct. The serum bilirubin level was checked and was found to be elevated. These findings suggested that there was an obstruction at the lower end of the common bile duct and the GP referred the patient to a gastroenterologist.

At the hospital, the patient underwent further investigations including blood glucose, CT scan of the upper abdomen including the pancreas, and endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERCP). His serum glucose was found to be mildly elevated, and the CT scan demonstrated a lesion in the head of the pancreas which was compressing the common bile duct. At ERCP, cytology brushings were taken from the pancreatic duct, which subsequently supported the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma at the head of the pancreas. During the same procedure, a short plastic tube (stent) was placed into the common bile duct to allow free drainage of bile from the liver.

Unfortunately, the tumour was found to be encasing the superior mesenteric artery and curative resection was not possible, as it would require division of the blood supply to the small bowel. Nonetheless, the patient’s symptoms from obstructive jaundice were relieved with the stent and pain control was achieved by injection of the nerves in the coeliac plexus.

Adenocarcinomas often present with insidious symptoms of unexplained back pain and weight loss. Weight loss is particularly marked in pancreatic cancer, perhaps because of malabsorption compounding the catabolic effects of the tumour. The non-specific nature of these symptoms can delay diagnosis and as a consequence, these tumours are often unresectable. Tumours that involve the head of the pancreas may present earlier because of obstruction to the common bile duct. The commonest symptoms are progressive jaundice due to obstruction of the bile duct, and steatorrhoea due to obstruction of the pancreatic duct and malabsorption of fat. Some early tumours of the head of the pancreas may be curable with radical surgery. The rarer endocrine tumours of the pancreas will often present with symptoms due to hypersecretion of hormones. An insuloma or glucagonoma may present with hypoglycaemia or diabetes, respectively, whereas a gastrinoma will present with intractable peptic ulceration and diarrhoea (Zollinger–Ellison syndrome).

It has long been recognized that pancreatic cancer is associated with maturity-onset diabetes. It was believed that the injurious process that caused diabetes resulted in subsequent tumour development. However, more recent studies have shown that pancreatic adenocarcinomas may secrete an anti-insulin factor that can cause diabetes, and removal of the tumour can be associated with restoration of normal glucose control. This could provide a future mechanism for earlier diagnosis of this increasingly common condition.

Treatment

Abdominal pain that is localized to the upper abdomen can be caused by any structure derived from the foregut. This would include conditions affecting the stomach, gall bladder, or pancreas. Pancreatic diseases may involve the coeliac plexus which lies in close proximity and results in pain that also radiates through to the back.

Investigation of the upper abdomen frequently identifies gallstones, but these are often asymptomatic and may not be the cause of the pain. The bile duct passes through the head of the pancreas before entering the duodenum, and as a consequence tumours in this area can compress the duct and obstruct the flow of bile from the liver. This results in (obstructive) jaundice. The bile duct and pancreatic duct can be visualized by endoscopy. The tissue of the pancreas is best demonstrated by a CT scan of the upper abdomen (see Fig. 4.6). At ERCP, cells that have been shed into the ducts can be sampled for microscopic evidence of neoplastic change (cytology). Because tumour tissue is generally friable this provides a useful method of diagnosis in less accessible tumours. A rigid plastic tube can be placed into the bile duct at endoscopy to relieve the obstruction (Fig. 11.4).

The superior mesenteric artery passes just posterior to the neck of the pancreas. This vessel supplies the whole of the midgut. It has to be preserved or the small bowel will be devascularized. If a tumour is involving this artery, surgical excision is impossible. Pain from advanced disease of the pancreas is often due to involvement of the nearby coeliac plexus of autonomic nerves. Injection of this region can safely obliterate the nerves and so help to reduce the pain.

Acute abdominal pain

Diagnosis of the cause of acute abdominal pain is one of the more challenging aspects of clinical medicine. Because of the lack of a somatic sensory nerve supply, identifying the diseased organ and the nature of the pathology requires a clear understanding of the anatomy, innervation and physiological function of the different gastrointestinal structures. There are two sources of intra-abdominal pain. Pain may arise from stimulation of the autonomic afferent nerves innervating the abdominal organs. This results in poorly localized abdominal discomfort that manifests in the region of the corresponding somatic afferent nerve root. This is known as referred pain. Because the gastrointestinal tract is derived embryologically from a mid-line structure, pain is referred to the mid-line, usually anteriorly. This is typified by inflammation of the appendix, which derives its autonomic nerve supply from the level of T10 (along with the rest of the midgut). Pain is therefore referred to the peri-umbilical region, which is innervated by somatic sensory nerves that enter the spinal cord at the same level (T10). Pain from the large bowel also refers to the mid-line, but to the infra-umbilical region. Pain from foregut structures (stomach and duodenum) is referred to the central upper abdominal region (epigastrium, see Fig. 11.1).

The second type of abdominal pain is due to inflammation of the overlying parietal peritoneum. This has its own somatic innervation and, therefore, results in well-localized pain over the area of inflammation. This is referred to as peritonism. In the case of appendicitis, pain moves from the peri-umbilical region to the right lower abdomen region (right iliac fossa) once the inflammatory process in the appendix penetrates through the serosal surface resulting in secondary inflammation of the overlying parietal peritoneum (Fig. 11.1).

The speed of onset of the pain can also help determine the nature of the organ involved. Very muscular structures with a narrow lumen will quickly cause severe pain if they become acutely distended (such as the ureter). Thin-walled distensible structures will, however, give rise to a pain of more insidious onset (gall bladder). Pain due to distension is initially due to stimulation of stretch receptors. As a consequence, the pain is often cyclical in nature (colic). This contrasts with pain from inflammation of tissue, which gives rise to a persistent pain (such as pancreatitis).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree