ESSENTIALS OF FOREIGN BODIES

ESSENTIALS OF FOREIGN BODIES

Plain films should be the initial diagnostic study; obtain both lateral and posteroanterior films of the neck, chest, and abdomen as indicated.

Avoid oral contrast as this may obscure endoscopic visualization.

Endoscopic evaluation may be required for objects that are potentially radiolucent in patients with a compelling history but negative imaging findings.

Impacted meat is typically radiolucent and is the most common esophageal foreign body in adults; perform endoscopy promptly in all cases with clinical evidence of obstruction and failure to pass on initial medical management.

Consider endotracheal intubation prior to foreign body extraction to protect the airway from both secretions and risk of aspiration of the foreign body upon retrieval.

Many foreign bodies pass spontaneously, but some objects (eg, sharp objects and batteries) require urgent intervention.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Gastrointestinal (GI) foreign bodies occur in all age groups and are commonly seen by the gastroenterologist, as well as by those in various surgical disciplines. The endoscopic removal of foreign bodies dates back to the early 1900s, with more widespread adoption following the advent of the fiberscope in 1957. Methods of diagnosis and treatment have continued to evolve since that time with the development of specialized accessories and improved procedural efficacy.

Foreign body ingestion, including dietary foreign bodies or food bolus impaction, currently represents the second most common indication for emergent gastrointestinal endoscopy, after gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Patients with foreign body ingestion typically present to their primary care physician or the emergency department, and the majority of foreign bodies pass spontaneously. Nevertheless, significant complications may arise resulting in approximately 1500–1600 deaths in the United States annually. Therefore, it is essential for the endoscopist to efficiently determine which patients require therapeutic intervention, and to be comfortable with proper methods of extraction. This chapter reviews indications for foreign body removal, the typical diagnostic evaluation, and endoscopic techniques for foreign body management.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Following foreign body ingestion patients may present in a variety of ways, ranging from asymptomatic to having signs and symptoms of complete esophageal obstruction or frank perforation. In the majority of cases a careful clinical history provides the correct diagnosis. Clinical history may be less reliable in children younger than age 5, the mentally ill, and in otherwise uncooperative patients. In such populations, symptoms and diagnostic studies are more critical to clarifying the diagnosis.

Most true foreign body ingestions are seen in children between the ages of 1 and 5 who swallow small household items or toys. Fortunately, most of these objects are small and blunt, and they typically pass spontaneously. Adults who ingest true foreign bodies often have psychiatric disturbance, mental retardation, alcoholism, or identifiable reasons for secondary gain, such as prisoners. Dietary foreign bodies and food bolus impactions typically occur in older adults, denture wearers, and those with underlying esophageal disorders.

Presenting symptoms are determined by the type of foreign body ingested and its location.

Esophageal foreign bodies may result in symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia, or signs of complete esophageal obstruction, including inability to swallow secretions, drooling, and regurgitation. Sudden onset of odynophagia following eating suggests impaction of a bone, sharp food fragment, toothpick, or similar objects in the esophagus. The importance of a thorough history was highlighted by a 2012 Centers for Disease Control Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report relating injuries from swallowed wire bristles of grill-cleaning brushes after consuming grilled foods as an increasingly common cause of esophageal foreign body in summer months. Respiratory symptoms such as coughing and stridor are common in younger children as their compliant tracheal rings are more easily compressed by an adjacent esophageal foreign body. Upper airway obstruction is a rare presentation for adults with an esophageal foreign body; however, meat bolus impaction at the level of the cricopharyngeus can result in respiratory obstruction, which has been referred to as “steak house syndrome.”

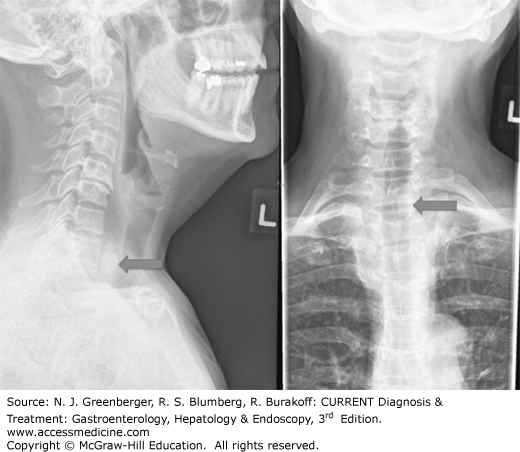

Plain films of the neck may demonstrate the location of a radiopaque object in the esophagus (Figure 35–1). Subcutaneous emphysema in the supraclavicular area or the neck suggests perforation of the esophagus or hypopharynx. Esophageal perforation by sharp objects at the level of the aortic arch may also result in an aortoesophageal fistula. This typically presents with a herald bleed, followed by massive hemorrhage. Fortunately these presentations are rare.

Gastric foreign bodies are generally asymptomatic, except when they are large enough to be associated with postprandial emesis and early satiety. Long-standing foreign bodies or those that are sharp and pointed may become impacted in the gastric wall and result in inflammation, ulceration, hemorrhage, or perforation. These patients often present with pain or bleeding.

Foreign bodies that have made their way to the small bowel typically remain asymptomatic if they are able to pass the fixed bend of the retroperitoneal duodenum. Symptoms of small bowel foreign bodies are typically those of perforation or obstruction.

Physical examination may yield important clues to identifying complications due to ingested foreign bodies. Crepitus in the supraclavicular and cervical areas suggests perforation of the hypopharynx or esophagus. Large gastric foreign bodies may occasionally be palpable on abdominal examination. Peritoneal signs often suggest gastric or intestinal perforation, and physical findings typical of bowel obstruction may occur with small bowel foreign bodies.

The plain film radiograph should be the initial diagnostic study. Both lateral and posteroanterior films should be obtained of the neck, chest, and abdomen. This is important in identifying small or flat objects that may overlie the spine, and in determining the exact location of a foreign body. The lateral film is often essential in differentiating between tracheobronchial and esophageal locations. Perforation may also be identified if the object is seen extending beyond the lumen wall, or if a soft tissue mass is seen adjacent to the object. Plain films should also be obtained to evaluate food bolus impactions, as the presence of bone fragments may alter the endoscopic management. If precise localization within the GI tract using plain films is difficult, computed tomography may aid in localization of a foreign body by adding a degree of dimensionality from plain film radiographs.

Objects that are relatively radiolucent, such as plastic, wood, most glass, and small bones, may not be seen on plain film, in which case xeroradiography or computed tomography may be helpful in making the diagnosis.

Contrast studies should be avoided. Gastrografin is contraindicated as it is hypertonic resulting in a severe chemical pneumonitis if aspirated, and barium can obscure endoscopic visualization, thereby complicating therapy.

Endoscopic evaluation may also be required, even in the absence of imaging findings, for a suspected radiolucent foreign body and compelling history. Additionally, endoscopy is often the therapeutic method of choice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree