In contrast, the overall prevalence of reflux esophagitis in Western countries has been estimated to be about 2% [33]. However, this figure likely underestimates the true prevalence. In a group of 27% of adults self-treating with antacids more than twice a month, objective evidence of reflux esophagitis is revealed in 84% during investigation, suggesting that esophagitis is not uncommonly found in those with symptoms of heartburn [37]. Furthermore, some have estimated that the prevalence of GERD is as high as 20% of the adult population and that esophagitis is found in 35-50% of those with GERD. If these data are correct the prevalence of esophagitis in the adult population may be as high as 7–10%. A recent systematic review by El-Serag has shown an overall increase in the prevalence of GERD over the past two decades, particularly for North America and Europe, but not Asia [38].

The incidence of GERD is estimated to be 4.5 per 100,000 with a dramatic increase in persons over the age of 40 years [39]. A Canadian study found that heartburn occurred at least once a week in 19% of persons > 60 years old, compared with 4.8% of persons < 27 years old [17]. A large American retrospective cohort study in VA patients also identified older age along with being a white male as the group associated with the most severe forms of GERD [40].

Nebel et al. in 1976 [16] studied the point prevalence and precipitating factors associated with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux using a questionnaire in 446 hospitalized and 558 outpatients (see Table 2.1). Age, sex or hospitaliza-tion did not significantly affect prevalence. In a Finnish study of 1700 adults, only 16% of symptomatic patients reported taking medications and only 5% had sought medical care [19].

In clinical practice, the relevant population is the group of patients that present with symptomatic heartburn. In this population, it has been estimated that about 50–70% of patients have normal endoscopies and the minority of patients (30–50%) have endoscopic esophagitis [41]. However, in a recently reported Canadian study of prompt endoscopy in patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia, the overall prevalence of endoscopic esophagitis was 43%, and in those with dominant heartburn, the prevalence of esophagitis was 55% [14]. Thus in this population, NERD was seen in less than half of the patients (45%).

In summary, the true population prevalence of GERD and esophagitis is unknown but appears to be approximately 10–15% and 3–7% based on current data.

Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease

GERD is primarily a motility and/or anatomical disorder of the esophagus, perturbations of which allow an abnormal amount or frequency of injurious gastric contents to reflux into the esophagus. Reflux occurs as a consequence of a defect of the normal anatomic and physiological anti-reflux barrier that is provided primarily by actions of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and crural diaphragm. The two key abnormalities are thought to be abnormal transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) [42, 43], precipitated by gastric distension in the postprandial period [44] and poor basal LES tone [42]. The result of these and other less common anatomic and physiological abnormalities is an increased intraesophageal exposure of gastric refluxate and increasing damage as the pH of reflux-ate falls below 4, which is optimal for pepsin activation [45, 46]. A hiatus hernia may act as a reservoir for acid refluxate that can then re-reflux up the esophagus [47, 48]. GERD patients with hiatus hernia have been found to have greater esophageal acid exposure and more reflux episodes vs GERD patients without a hernia [49].

Pathophysiology in non-erosive reflux disease

Further support for the concept that acid alone can be the pathophysiological basis for reflux disease comes from the observation that in patients that have typical symptoms of reflux with a normal endoscopy, 6–15% with symptomatic reflux had normal 24-hour esophageal pH-metry [50–52]. Additionally, pathological reflux on pH studies has been identified in 21–61% of endoscopy negative patients [53–55]. A recent study identified abnormal acid reflux in 84% of patients with either erosive esophagitis or NERD, a much higher proportion than previously reported. The reason for these variable results is unknown. In contrast, 71–91% of patients with erosive esophagitis at endoscopy have pathological reflux on pH studies. Thus, abnormal intraesophageal acid exposure as measured by pH studies is more frequent but not an optimal gold standard for documenting reflux disease [53–55]. However, despite these limitations the data clearly demonstrate that the proportion of intraesophageal acid exposure increases over the spectrum from NERD to worsening grades of esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus [56].

Another conundrum in reflux disease is the patient with an apparent suprasensitive esophagus. Of 96 patients with normal 24-hour esophageal acid exposure, 12.5% were found to have a statistically significant association between their reflux symptoms and actual reflux episodes, despite having “normal” intraesophageal acid exposure [51]. In these patients, the duration of reflux episodes was shorter and the pH of reflux episodes was often lower than in patients with typical GERD, suggesting that esophageal hypersensitivity was the cause of their symptoms. These and other data have led to the concept of an acid-sensitive esophagus.

An esophageal balloon distension study provided further experimental evidence of esophageal hypersensitivity in patients with normal acid exposure times with a value for a symptom index (SI) > 50% [50]. In general, these patients had significantly lower thresholds for initial perception and discomfort from esophageal balloon distension, compared with both normal controls and patients with confirmed reflux. In contrast, Fass et al. studied patients with GERD and controls without GERD and determined that patients showed enhanced perception of acid perfusion but not of esophageal distension [57]. They concluded that chronic acid reflux by itself was not the cause of esophageal hypersensitivity to distension in patients with non-cardiac chest pain, although subsequent data from this group suggest that the esophagus can be primed to be hypersensitive by repeated reflux events.

Carlsson et al. [58] have also demonstrated an impaired esophageal mucosal barrier in symptomatic GERD patients by measuring the transmucosal epithelial potential difference, suggesting a role for alteration in cell barrier function as a cause for reflux symptoms in some individuals.

Another study examined differences in spatiotemporal reflux characteristics between symptomatic and asymptomatic reflux episodes [59]. They used a pH sensor positioned 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15cm above the LES and found that the duration of acid exposure was longer and the proximal extent was higher in symptomatic than in asymptomatic reflux episodes. A similar study also determined that patients with NERD compared with healthy controls, had a higher, intraesophageal proximal reflux of acid [60]. Even NERD patients with normal acid exposure time seemed to perceive proximal reflux very readily, implying that their proximal esophageal mucosa is more sensitive to short duration refluxes than that of patients with esophagitis.

More recently, there is a suggestion that up to two-thirds of patients with NERD have histological evidence of esophageal injury [61]. The commonest finding is dilation of intercellular spaces irrespective of esophageal acid exposure. Basal cell hyperplasia and papillary elongation were seen more frequently in NERD patients with abnormal acid exposure. However, these findings are not found consistently enough to reliably serve as the basis for the diagnosis of GERD.

Hiatus hernia

The mere presence of a hiatus hernia (HH) bears no relationship to the diagnosis of esophagitis and is frequently seen in those without esophagitis. Moreover, up to half the healthy population has a hiatus hernia [62] and only half of the patients with symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation have a hiatus hernia [63]. However, some studies have suggested that patients with a hiatus hernia have greater esophageal acid exposure and more reflux episodes [49] and more severe reflux esophagitis than patients without, suggesting that a HH does have a role in some patients with reflux disease [64, 65]. A large HH may act as a reservoir for acid that re-refluxes more readily when a swallow is initiated and in this fashion contributes to GERD [47,48].

Other supporting evidence for the role of HH in GERD comes from a study in patients with pathologic reflux (pH < 4 for more than 5% of a 24-hour intraesophageal pH-metry study) that identified hiatus hernia in 71% of patients with mild esophagitis, compared with 39% of those without esophagitis [66]. Patients with a hiatus hernia also had higher 24-hour intraesophageal acid exposure compared with those without, particularly during the night. However, there were no differences in symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation, whether or not patients had a hiatus hernia or esophagitis.

Another study demonstrated that the presence of hiatus hernia correlated with more severe manifestations of GERD [67]. Hiatus hernia was seen in 29% of symptomatic patients, 71% with erosive esophagitis, and 96% with long segment Barrett’s esophagus.

Although transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) are thought to be a key mechanism for pathological reflux, van Herwaarden et al. [49] did not find differences in LES pressure, and the incidence of TLESRs, and the proportion of TLESRs associated with acid reflux were comparable in those with and without hiatus hernia. They felt that the excess reflux in GERD patients with hiatus hernia was caused by malfunction of the gastroesophageal barrier during low LES pressure, swallow-associated normal LES relaxations, deep inspiration and straining.

In summary, the pathophysiology of GERD is varied, and the most common mechanism appears to be TLESRs but mechanical defects of the gastroesophageal junction and LES also play a role in many patients with this disorder.

Natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease

There are few data about this important topic, and existing studies are limited in that they usually include heterogeneous populations. In one such study using a Swedish population-based survey of over a thousand citizens conducted over seven years, the prevalence of GERD remained stable over time at about 17–19% [68]. In a more recent 10-year follow-up Swedish study of 197 respondents out of the original 337 subject cohort, 83% reported no change in their global symptom assessment, indicating relative stability of symptoms over time [69].

A small retrospective study published in 1991 identified patients with symptoms of GERD but with a normal endos-copy and 24-hour pH study [70]. All patients received antacids or prokinetic drugs or both for 3-6 months. Thus, this was not a study of untreated patients but a study that employed treatments now recognized to be relatively ineffective (vs true untreated controls). However, 19 of the 33 patients still had symptoms at the end of six months and of these, five (26%) developed erosive esophagitis. The remainder of the patients remained asymptomatic. There was no difference in baseline pH-metry between those that went on to develop esophagitis and those that did not.

Another study reported data on patients with objectively proven GERD conservatively managed without treatment over a 17–22-year follow-up [71]. The authors reported on 60 patients from an initial cohort of 87 patients. Ten of these patients ultimately had an anti-reflux procedure, but of the remaining “untreated” 50 patients, 36 (72%) were less symptomatic at follow-up. Of this group, only six became symptom “free”. The majority no longer used anti-reflux medications. Only five patients remained unchanged and nine became worse. The prevalence of erosive esophagitis fell from 40% at referral to 27% at follow-up endoscopy, and six new cases of Barrett’s metaplasia developed. At follow-up, 66% of the patients had objective evidence of GERD with esophagitis, a pathological pH study or newly recognized Barrett’s metaplasia. Neither the presence of esophagitis or of hiatal hernia, nor the severity of symptoms at baseline predicted the course of the disease at follow-up. The authors concluded that the severity of reflux symptoms declined in the long term, but pathological reflux persisted in the majority of the conservatively managed patients.

For patients with mild esophagitis, the course of the disease may also be relatively benign from an oesophageal injury perspective, with only 23% progressing to more severe esophagitis, while 31% improved and 46% spontaneously healed with no further episodes. However, from an impact on quality of life GERD does not appear to be a benign disease. In one study, patients with endoscopic esophagitis diagnosed more than 10 years earlier were contacted by postal questionnaire and phone interview [71]. Of the respondents, over 70% continued to have significant symptoms of reflux, and 40–50% were still taking acid sup-pressive medications regularly and had reduced QoL (lower Short Form (SF)-36, physical and social function domain scores). Thus, GERD is a chronic disease with significant morbidity and it impacts negatively on QoL.

Despite frequent symptoms, even severe reflux disease has little effect on life expectancy, with almost no deaths directly due to GERD reported in long-term follow-up [39, 71, 72]. However, a recent population-based study identified GERD as a strong risk factor for esophageal adenocar-cinoma, but not squamous cell carcinoma [73].

In summary, the above data indicate that GERD is a chronic but not static disease; progression and regression may occur, although this is not common. Despite impacting QoL adversely, GERD has little effect on life expectancy.

Esophageal complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease

Complications of GERD include bleeding (< 2%), ulcera-tion (approximately 5%) and strictures (1.2% to 20%) [71, 74, 75]. Patients with strictures are generally older and more frequently have a hiatus hernia [74]. Barrett’s esophagus has been identified in 10–20% of GERD patients [76]. Six of 50 patients (12%) developed Barrett’s esophagus during approximately 20 years of follow-up, a crude incidence of 0.6% per year [72]. The association of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma are covered in Chapter 3.

Effects of gastroesophageal reflux disease on quality of life (QoL)

Increased attention is being paid to patient QoL assessments, as opposed to histology of the esophagus as an outcome measure of importance in patients with GERD. Indeed, as there is no single physical marker for this disease, most experts now include decrements in QoL as part of the definition of GERD [9]. Several general health status and reflux-specific QoL instruments have been developed, validated and used. Examples include: Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 [77], psychological General well-being (PGWB) index [78], the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) [79–81], the Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease – Health Related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) instrument [82], ReQuest [83–85], Reflux Disease Questionnaire [86], REFLUX-QUAL (RQS) [87], the Reflux questionnaire [88] and the Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia questionnaire (QOLRAD) [89]. Because of the development and availability of QoL instruments, more recent GERD clinical studies have used validated GERD-specific instruments focusing more on assessing patient satisfaction and QoL as primary endpoints [89-96]. Despite the development of more specific health-related QoL questionnaires, a 2008 systematic review identified that existing scales were still somewhat suboptimal [97]. Patients with gastrointestinal disorders have decreased functional status and well-being [98]. Those patients with chronic gastrointestinal disorders, including GERD, and congestive heart failure have the poorest health perceptions. These perceptions are worse than those that characterize some other chronic conditions such as hypertension and arthritis [79, 99,100]. In patients with heartburn there was a substantial impairment of all aspects of health-related QoL when measured using the GSRS, QOLRAD, SF-36 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale [98].

Other studies have shown that successful treatment of GERD results in improvement in QoL. In general, patients with reflux esophagitis are considered to have equally impaired QoL to those with non-erosive disease, but those with very severe reflux esophagitis may have even more impairment [101]. NERD patients do not have objective markers such as endoscopic esophagitis that can be used to define treatment success. Symptom reduction to a level that does not cause significant impairment of health-related QoL is therefore an appropriate outcome by which to measure a therapy. Both the PGWB and GSRS scores show good discriminative ability to reflect the severity of impairments in quality of life inNERD patients [102]. Improvements in health-related QoL with treatment of NERD and of erosive esophagitis have also been documented [7, 103, 104]. There are also now scales such as the Proton pump inhibitor Acid Suppression test (PASS) [105], the Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease impact scale [106] and the Reflux Disease Questionnaire (RDQ) [107] that have been developed as instruments to help guide patient care.

In summary, these data demonstrate that the impact GERD has on QoL is substantial and equivalent to many other diseases considered to be severe and important.

Diagnostic tests for gastroesophageal reflux disease

The diagnosis of GERD depends on the definition of “pathological” in diagnostic tests. Problems in defining GERD have been recognized for more than two decades [62]. Methods of diagnosing GERD are outlined in Table 2.2. These tests evaluate different features of GERD, and none of them measures all aspects of the disease. Tests such as barium studies, scintigraphy and ambulatory oesophageal pH studies demonstrate whether reflux is occurring; endoscopy demonstrates mucosal injury and complications of GERD; ambulatory oesophageal pH studies quantify the amount of oesophageal acid exposure, the number and duration of reflux events and allow the correlation of reflux events with recorded symptoms; oesophageal sensitivity to acid is assessed by the Bernstein test. The correct interpretation of these diagnostic tests for GERD is critically important. For example, a patient with documented endoscopic esophagitis with a negative Bernstein test should not be regarded as having a “false negative” Bernstein test, but rather an acid insensitive esophagus as measured by this test. With variable patient populations, and with differences in definitions, techniques and gold standards, it is impossible to compare sensitivity and specificity values between the various diagnostic tests for GERD [108].

Manometry and lower esophageal pressure measurement

LES pressures alone are not of diagnostic value, as there is considerable variation in the normal LES pressure as well as overlap of pressures in those with and without esophagitis. Furthermore, the most common finding of an LES pressure in patients with GERD is a normal one. In a review of six studies [109], LES pressure < 10mmHg did correlate with abnormal oesophageal acid exposure but with a sensitivity of only 58% and specificity of 84%. However, there may still be some utility in low LES pressures as a predictor for identifying patients with the most severe reflux or in identifying those at higher risk of complications associated with regurgitation [62]. Manometry prior to surgery has been advocated to document a mechanically defective lower esophageal sphincter [110], but there is no good evidence that this affects outcome. Some experts still advocate for preoperative manometry in GERD patients as it also measures distal esophageal amplitudes, a measure that may affect surgical decision making (type of wrap, whether to perform the surgery, etc.).

Table 2.2 Summary of diagnostic tests in gastroesophageal reflux disease.

| Test | What does it measure? | Comments |

| Esophageal manometry | • Measures lower esophageal sphincter pressure • Low (< 10 mmHg) LES pressure: 58% sensitivity and 84% specificity for abnormal oesophageal acid exposure [109] • Does not measure risk for reflux or assess for the presence of esophagitis | • Overlap with normal prevents one from using LES pressure as a diagnostic criteria for GERD • Does not detect transient LES relaxation • May be useful in pre/ post operative evaluation |

| Radiology | • Demonstrates some of the morphological findings of GERD, for example strictures and ulcers • Detects gastroesophageal reflux but cannot differentiate pathological reflux of GERD from physiological reflux of normals • Detects hiatus hernia • Poor detection for mild esophagitis 0–53% [111] • Does not assess symptom correlation with reflux event | • In patients with GERD detects reflux in 10-50% [111] • Unclear role in most patients with GERD • Presence of a hiatus hernia does not correlate with GERD [111] |

| Scintigraphy | • Detects gastroesophageal reflux but cannot differentiate pathological reflux of GERD from physiological reflux of normals | • Sensitivity 14-86% [111] • Requires radioactivity exposure |

| Endoscopy | • Detects esophagitis, strictures and Barrett’s esophagus • Allows biopsy, but esophageal histology has limited utility | • Lacks sensitivity |

| Bernstein (acid perfusion test) | • Measures esophageal acid sensitivity • Can be positive in patients with normal endoscopy and normal oesophageal pH studies (hypersensitive esophagus) • Determines oesophageal origin of pain | Sensitivity 42-100%, mean 77% [111] • Specificity 50-100%, mean 86% [111] • May be useful in patients with atypical symptoms and NCCP |

| Esophageal pH monitoring | • Catheter based • Quantifies gastroesophageal reflux • Allows assessment of whether “pathological reflux” occurs • Allows for determination of a symptom index (correlation between symptoms and reflux events) • Does not detect mucosal damage • Wireless pH testing • Longer duration of measurement possible | • Normal in 14-29% of those with esophagitis • Normal in 6-15% of patients with abnormal SI • Better patient tolerance |

| SI with oesophageal pH monitoring | • Correlates symptoms with reflux events | • Bimodal predictive value • Can be positive when pH study is normal |

| PPI test | • Positive test suggests acid reflux as probable cause of symptoms | • Simplicity, reduced cost |

GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; LES: lower esophageal sphincter; SI: symptom index; NCCP: non-cardiac chest pain; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

Radiological diagnosis

A variety of outcome measures have been used in studies of the use of radiology procedures in GERD. Some of these tests have assessed gastroesophageal reflux (with and without reflux provoking maneuvers) and correlated this with other measures of reflux such as esophageal pH studies. Other studies and tests examined the ability of radiological studies to identify esophagitis.

The radiological diagnosis of esophagitis is generally considered to be unreliable, especially in mild reflux esophagitis. The diagnostic accuracy of barium radiography compared with endoscopy has been demonstrated to be 0–53% for mild, 79–93% for moderate and 95-100% for severe esophagitis [28, 111]. Many of the early studies [112] compared radiological techniques to endoscopy as a gold standard. By 1980, it was recognized that about half the patients with symptomatic reflux did not have endoscopic esophagitis [54, 62]. Thus, many, if not most, patients with GERD would be expected to have normal barium studies. Additionally, from a technical perspective, the gastroesophageal junction (the site most involved by oesophageal inflammation, and fibrosis) is not well visualized in up to a third of patients, due to inadequate distension [112, 113].

Documenting that reflux occurs during a radiological examination does not determine whether patients have GERD, nor does it correlate with patients’ symptoms. With provocative tests, reflux is seen in 25–71% of symptomatic patients but also is noted in 20% of controls [114]. Low density contrast medium does not improve the diagnostic accuracy over that observed with the use of regular barium contrast [115]. When taken as a whole, radiological studies are frequently falsely negative in patients in whom endoscopy or esophageal pH-metry studies are abnormal and are not recommended as a diagnostic test for GERD.

Measurement of the internal diameter of the cardiac esophagus was shown to predict 89% of patients with mild endoscopic esophagitis [116]. However, this was not confirmed in a study that found that the gastroesophageal junction could not be adequately visualized in 29% of patients [112].

Free, severe reflux as seen on barium studies may be a highly specific predictor of reflux as defined by esophageal pH monitoring [109, 112, 117, 118]. However, esophagitis is often not diagnosed radiographically in patients with abnormal intraesophageal pH studies [119].

Scintigraphy

Reflux can also be measured following the ingestion of a liquid containing a radiolabeled pharmaceutical such as sulfur colloid or 99mTc in an acidified liquid suspension. This procedure is similar to the assessment of reflux during radiology, although scintigraphy may be superior in this regard [63]. Graded abdominal compression to induce and detect reflux is unreliable, with variable sensitivity of 14-90% [63, 111, 112, 114,120]. The biggest problem with this method of testing for reflux appears to be the short duration of the imaging test, as reflux occurs intermittently and therefore can often go undetected in any study of short duration that depends on demonstrating abnormal frequency of reflux as part of the diagnostic criteria. With the availability of endoscopy and intraesophageal pH monitoring, this test also appears to have little value in the diagnosis of GERD.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Endoscopy provides the most accurate means of assessing mucosal detail of the esophagus, but remains insensitive in diagnosing reflux. Definite endoscopic reflux esophagitis is unequivocal evidence that the patient suffers from GERD. However, patients with an “acid sensitive” esophagus who experience symptoms in the absence of esophagitis (the majority of patients with reflux) cannot be diagnosed by endoscopy. Recent efforts attempting to increase the sensitivity of endoscopic detection of the mucosal changes of GERD using imaging enhancements such as narrow band imaging (NBI) have not been as promising as hoped. The intraesophageal pH study is abnormal in 50% or more of patients with reflux symptoms and normal endoscopy [54, 121]. Thus, using current endoscopic technology, a negative endoscopy does not exclude GERD. Histological diagnosis of reflux may be more sensitive than endoscopy alone in diagnosing reflux, but the sensitivity of this test is problematic due to inadequate size of the biopsy [122], patchy distribution of the histological findings [123] or minimal changes with variable interpretation [124].

Berstad and Hatlebakk [125] prospectively evaluated patients with GERD using their own unique endoscopic grading system. Those with “true” GERD all had endoscopic findings according to their classification, but the presence of whitish exudate in the lesions and the width of the lesions were the only two endoscopic features that correlated with the severity of esophageal acid exposure as measured by pH-metry [126]. Confirmatory data from other investigators using this endoscopic classification are lacking.

Previously, the most widely applied esophagitis grading system had been the Savary-Miller classification in the original and modified forms. A newer classification [127], which measures metaplasia, ulcer, stricture and erosions (known as the MUSE classification), records the degree of severity of each as absent, mild, moderate and severe. This is now adapted as the Los Angeles (LA) classification and is the one that is now most commonly used [118]. The key features are:

- Grade A: one (or more) mucosal break no longer than 5 mm that does not extend between the tops of two mucosal folds

- Grade B: one (or more) mucosal break more than 5 mm long that does not extend between the tops of two mucosal folds

- Grade C: one (or more) mucosal break that is continuous between the tops of two or more mucosal folds but which involves less than 75% of the circumference

- Grade D: one (or more) mucosal break which involves at least 75% of the esophageal circumference [128]

The LA classification has been tested in a study that evaluated the circumferential extent of esophagitis by the criterion of whether mucosal breaks extended between the tops of mucosal folds and gave acceptable agreement (kappa 0.4) among observers [128]. Severity of esophageal acid exposure was significantly (P < 0.001) related to the LA severity grade of esophagitis. The pretreatment esophagitis grades A–C were related to heartburn severity (P < 0.01), outcomes of omeprazole treatment (P < 0.01), and the risk for symptom relapse off therapy (P < 0–05).

Bernstein test as a measure of esophageal acid sensitivity

This test was first described in 1958 and used to attempt to distinguish chest pain of esophageal from that of cardiac origin [129]. In an early 1978 prospective, comparative study of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, upper gastrointestinal barium series, esophageal manometry and the Bernstein test in patients with suspected reflux esophagitis, the Bernstein test had the greatest sensitivity (85%) for diagnosing esophagitis. However, there were many false positives, as half the patients without esophagitis also had a positive Bernstein test. The lack of specificity for esophagitis is not very surprising, since most of these patients are now considered to have an acid sensitive esophagus, consistent with NERD. Another study found the sensitivity of the Bernstein test to be 70% in patients with typical reflux symptoms. However, 97% of patients with a negative test had either endoscopic, histologic or scintigraphy evidence of GERD [130]. In a review of seven studies [131], the overall sensitivity of this test was 77% and specificity 86%. Although the Bernstein test does not establish that there is mucosal damage (esophagitis), and patient acceptance is limited, a positive test result (defined as reproduction of symptoms during acid perfusion and not during saline perfusion) implies that the esophagus is likely to be the origin of the symptoms.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring

Catheter based esophageal pH recordings have been used for over 30 years. Previous versions of this chapter have critically reviewed and covered the standards and thresholds of esophageal acid exposure. Whether an abnormal intraesophageal pH study is the gold standard for diagnosing GERD remains controversial [54]. This test is useful in quantifying the amount and frequency of acid reflux that occurs. However, it can be difficult to separate physiological from low-level pathological reflux, and the threshold levels that separate “normal” from “abnormal” test results are not clear. A cutoff pH of 4 to define pathological reflux has been validated with catheter based systems [108,132]. Furthermore, this pH threshold makes physiological sense, as proteolytic activity of pepsin is low at a pH above 4, and high below pH 3 [46]. Unfortunately, even this cutoff may mischaracterize up to 50% of reflux episodes [133]. The technique has many limitations, including lack of availability, invasiveness, cost, lack of patient acceptability, debatable reproducibility, and technical problems such as improper placement of the pH probe, probe failures and recording device failures [134].

The technique is now improved with a wireless pH monitoring method [135]. The main advantage is that a patient does not have to walk around with a conspicuous and uncomfortable transnasal catheter. Since patients do not restrict their usual daily activities, the results are considered to be a more reflective and accurate identification of the true intraesophageal acid profile. The Bravo system is an example that transmits esophgeal pH data every six seconds. With this new technique, thresholds were re-established and an acceptable discriminating threshold was determined to be 5.3% of 24 hours. The capsule is placed endoscopically and clipped into place 6cm above the squamocolumnar junction. While a foreign body sensation is felt by the patient, the discomfort is minimal. As the capsule is clipped into place, prolonged pH measurements are possible and this factor may increase the sensitivity for the diagnosis of GERD [136, 137]. However, capsule detachment can occur and esophageal perforation has been reported [135].

These tests may be useful for investigating patients with atypical reflux symptoms or non-cardiac chest pain in whom GERD is suspected to be the cause of symptoms.

Symptom index (SI)

A quantitative method for correlating symptoms and esophageal acid reflux events was developed in 1986 and called the “symptom index”. This index is calculated as the number of times the symptom occurred when the pH is < 4, divided by the total number of symptoms, multiplied by 100. Initial validation studies in 100 patients found the SI to be distributed in a bimodal fashion. Of patients with SI above 75%, 97.5% had an abnormal esophageal pH study [138]. If the SI was less than 25%, the proportion of patients with a normal esophageal pH study was 81%, and 90% of this group had a normal endoscopy [139]. Endoscopy was normal in nearly 30% of patients with a high SI. Thus, if endoscopy is found to be normal in the course of evaluating patients suspected of having GERD, an esophageal pH study combined with a measurement of SI may be a useful diagnostic test. There was very poor correlation between results of the Bernstein test and the SI. The negative predictive value of a low SI is useful. A limitation of the SI is that it does not take into account the reflux episodes that were symptom free. The SI was not found to be useful for diagnosing non-cardiac chest pain [140]. The next method to be developed was the symptom sensitivity index (SSI) that failed to take into account the total number of symptom episodes [141].

The symptom association probability (SAP) is another method that has been developed, with the intent to reduce the shortcomings of the SI [142]. This method correlates pH data during both symptomatic and asymptomatic reflux episodes and requires further validation, although some experts have suggested that this index is superior to the SI [135].

All three methods: SI, SSI and SAP were prospectively compared using symptom response to high dose omeprazole. SSI and SAP had better sensitivities of 74% and 65% compared to 35% with SI, but none predicted the response to PPI particularly well [143]. In summary, these data demonstrate that an objective gold-standard diagnostic test for GERD is lacking. Endoscopy has insufficient sensitivity but high PPV. Esophageal ambulatory pH monitoring has the highest diagnostic test sensitivity for GERD.

Symptoms as a diagnostic test for GERD

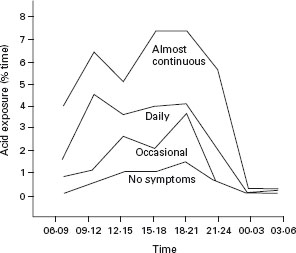

An important study of patients with reflux-like symptoms was reported by Joelsson and Johnsson [144]. Erosive esophagitis (Savary-Miller grade I or worse) was identified in a third of patients with symptoms of GERD. Whether the patient had erosive disease or not, the frequency of heartburn and acid regurgitation correlated with median esophageal acid exposure time, measured by 24-hour pH monitoring. Although patients with an endoscopically normal esophagus had lower overall median acid exposure, there was a trend towards more acid exposure in those with more severe symptoms. Figure 2.1 shows the relationship between severity of symptoms and acid exposure time. The authors concluded that reflux-like dyspepsia is accompanied by increased esophageal acid exposure, a finding that is supported by others [55,145]. Unfortunately, severity of symptoms is still a poor predictor of mucosal damage [54,146,147].

Figure 2.1 Acid exposure of the distal part of the esophagus during eight three-hour periods expressed as median% time spent with pH < 4 in 190 patients with different degrees of heartburn and acid regurgitation and 50 asymptomatic endoscopically normal subjects. Reproduced with permission from Joelsson B et al. Gut 1989; 30: 1523–1525 [144].

Johannessen et al. [148] determined that the symptom of heartburn showed the best discrimination for patients with esophagitis. Typical symptoms of GERD, such as heartburn, correlate with abnormal intraesophageal pH exposure in 56–73% of patients [29, 54].

In an effort to improve the diagnostic value of the symptoms of GERD based on the patient’s history, investigators have applied structured questionnaires [149–154]. Using the questionnaire developed by Johnsson [149], a positive response to all four questions was required to achieve a high positive predictive value, thus limiting its usefulness. The description of symptoms as opposed to using the term heartburn, may be a factor that improves the predictive value of this questionnaire.

DeMeester reported a retrospective review of 100 consecutive patients with symptoms of GERD [54]. The combination of the presence of grade II or III symptoms on the standardized questionnaire and endoscopic esophagitis, predicted increased acid exposure on 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring, with a specificity of 97% and a positive predictive value of 98%.

The Carlsson-Dent questionnaire that is intended to identify responders to PPI therapy has been extensively validated for reflux esophagitis detected at endoscopy and abnormal 24-hour intraesophageal pH-metry [150]. The questionnaire has a maximum score of 18. In the endoscopic comparison, using a threshold score of 4, the questionnaire had 70% sensitivity but only 46% specificity for diagnosis of esophagitis. When used in dyspeptic patients, the questionnaire had a sensitivity of 92% but a specificity of only 19% for diagnosis of GERD when compared with abnormal 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring. The mean score of 11 for GERD patients was higher than that observed in the dyspepsia cohort (mean 4.6). Symptom relief during treatment with omeprazole was predicted by the presence of heartburn, described as “a burning feeling rising from the stomach or lower chest up towards the neck” (odds ratio 4) and by “relief from antacids” (odds ratio 2.2). Even in a non-ulcer dyspepsia study from which patients with predominant heartburn were excluded, 42% of the patients indicated that they had a “rising burning feeling”, a description that has been validated to define GERD-related heartburn in the Carlsson-Dent questionnaire. Even in this group of presumed non-GERD patients, those patients who answered positively to this key question had the best symptom relief with omeprazole. One prospective validation of this questionnaire in a primary care population did not find that the questionnaire was better than the physician’s provisional diagnosis for discriminating omeprazole responders [155]. The utility of this questionnaire as a clinical practice tool appears to be limited, although it remains an important tool for research purposes because it allows for stratification of patients enrolled in GERD studies.

Similar in its goal to the Carlsson-Dent questionnaire, the 12-item “GERD Screener” demonstrated construct, convergent and predictive validity. This instrument was practical, short and easily administered and was intended to serve as a valuable case-finding instrument in primary care and managed care organizations [154].

Locke et al. [156] developed a GERD questionnaire in 1994 [152] and used it in a study in which patients underwent open access endoscopy. The study provided evidence that heartburn frequency was associated with esophagitis, that duration of acid regurgitation was associated with Barrett’s esophagus and that strictures were associated with dysphagia severity and duration. Unfortunately, despite these somewhat encouraging findings, the questionnaire overall was only able to modestly predict endo-scopic findings. This questionnaire has also been adapted to the Spanish population with excellent reproducibility and concurrent validity [157].

Subsequent validated GERD questionnaires focused more on creating instruments for assessing QoL rather than for diagnosis of GERD [89-95]. However, a new, reliable and valid questionnaire to better diagnose GERD was developed [153] and the internal consistency, interobserver reliability, criteria validity using 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring, construct validity and extreme group validation were assessed using patients with pathologic GERD. This questionnaire had sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values of over 90%, while the negative predictive value was 79% [153]. A new Chinese GERD questionnaire was found to discriminate between controls and GERD patients with a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 84% [158].

In summary, these data indicate that at the present, symptom based questionnaires have been demonstrated to be useful research tools but they are of insufficient validity or are too complicated to use to be useful in clinical practice.

Therapeutic trial of acid suppression as a diagnostic test for GERD

All of the diagnostic tests described above are cumbersome or invasive and they detect different aspects of reflux. PPIs are the most effective intervention for all grades of esophagitis and for treatment of symptoms such as heartburn. The therapeutic response to a trial with a PPI was therefore thought possibly to be useful in diagnosing GERD in a variety of patient populations including patients with typical symptoms of GERD (heartburn), patients with GERD-related non-cardiac chest pain, and patients with positive and negative findings for GERD on endoscopy or pH monitoring. The variation of patient populations studied makes direct comparisons between studies impossible.

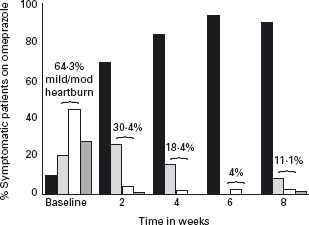

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of patients with reflux symptoms (92% had heartburn) and only minor or no esophagitis at endoscopy, patients were randomized to receive omeprazole 40 mg once daily or a placebo for 14 days [159]. A 75% reduction in heartburn was considered to be a positive diagnostic test. There was a significant (P = 0.04) correlation between response to the PPI and the results of the pH-metry. A response to PPI occurred in 68% of patients with abnormal reflux and in only 37% of patients with a normal pH study. Only 13% of patients responded to placebo.

A randomized trial of omeprazole 20 mg twice daily or placebo for one week tested the efficacy of omeprazole to diagnose reflux disease among dyspeptic patients [160]. A diagnosis of GERD was made on the basis of either grade II–III esophagitis or esophageal reflux with pH < 4 for more than 4% of the esophageal pH monitoring time. Using this definition, 135 of 160 (84%) patients were found to have GERD. Of those patients with presumed NERD, 63% had an abnormal pH study. Twenty percent (18/92) of patients with esophagitis had normal pH studies. Using symptom improvement of at least one grade for the definition of a positive test, the “omeprazole test” had a sensitivity of 71–81% for diagnosing GERD, compared with the sensitivity of placebo of 36–47%. With a more stringent definition for a positive test of total symptom relief, the sensitivity of omeprazole to diagnose reflux was lower at 48–59%, compared with 6–19% for placebo. However, the specificity of the test was also low, and actually was higher with placebo than with omeprazole. Thus, the test in this study was more useful for ruling out the diagnosis than for ruling it in. Even patients who did not have GERD by definition had better symptom relief with omeprazole than with placebo. These may be patients with an acid sensitive esophagus who respond well to acid suppression despite their esophageal pH being within normal limits.

A recent UK study of 90 patients with dyspeptic symptoms suggestive of GERD evaluated the cost-effectiveness of an open course of treatment with omeprazole 40 mg daily for 14 days as a diagnostic test [161]. The cost per correct diagnosis was £47 for omeprazole (95% CI: £40 to £59) compared with £480 for endoscopy (95% CI: £396 to £608). The authors concluded that an empirical trial of omeprazole was cost-effective both for symptom relief and for diagnosing GERD in patients with typical symptoms.

In a small, four-week, randomized placebo-controlled crossover study [162] in patients with normal endoscopy and esophageal pH-metry, but with an SI of > 50, 10 of 12 (83%) of patients with a positive SI showed improvement on omeprazole 20 mg twice daily for decreased symptom frequency, severity and consumption of antacids (P < 0.01). The SF-36, QoL parameters for bodily pain and vitality also significantly improved. In the group with a negative SI only one patient clearly improved.

Thirty-three consecutive patients with symptoms of reflux, abnormal pH studies, but normal endoscopies were sequentially allocated to receive ranitidine 150 mg twice daily, omeprazole 40 mg once daily, or omeprazole 40 mg twice daily for 7–10 days [163]. On the last day of treatment an esophageal pH study was repeated, and the results were correlated with symptoms. Using a 75% reduction in symptoms as a positive test, and the pH test as the gold standard, the sensitivity of the omeprazole test using a dose of 40 mg twice daily was 83.3%, while the sensitivity with omeprazole 40 mg once daily was only 27.2%. The authors concluded that the diagnosis of GERD could be ruled out if a patient failed to respond to a short course of high dose PPI.

Fass et al. [164] also used an omeprazole 60 mg daily test versus placebo in GERD positive (35/42, 83%) and GERD negative patients (17%). Twenty-eight GERD-positive and three GERD-negative patients responded to the omeprazole test, providing sensitivity of 80.0% and specificity of 57.1%. Economic analysis revealed that the omeprazole test saved US$348 per average patient evaluated, with 64% reduction in the number of upper endoscopies and a 53% reduction in the use of pH testing.

Most studies have used omeprazole in the “PPI test”. However, a study using 60 mg of lansoprazole once daily versus placebo for five days found that 85% tested positive during active treatment compared with 9% with placebo [165]. The PPI test sensitivity was 85% and specificity was 73%.

Esomeprazole is more potent than omeprazole and it also has been evaluated as a diagnostic tool [166]. Patients (n = 440) were randomized to receive esomeprazole 40 mg once daily, esomeprazole 20mg twice daily or a placebo for 14 days. Endoscopy and 24-hour esophageal pH-monitor-ing were carried out to determine the presence of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). The esomeprazole treatment test had sensitivity in confirming the diagnosis of GERD of between 79% and 86% (for the two doses of PPI) after five days, while the corresponding value for placebo was 36%.

In a small, eight-week, placebo-controlled study of 36 patients with non-cardiac chest pain and abnormal esophageal 24-hour pH-metry, overall pain improvement was reported by 81% of omeprazole and 6% of placebo-treated patients [167]. Similar results were reported in another small study of 39 patients [168]. The omeprazole test correctly classified 78% of patients considered to be GERD patients by 24-hour esophageal monitoring and/or endoscopy and was positive in only 14% of patients considered not to have GERD by these criteria. Thus, a therapeutic trial may be useful in conditions other than typical GERD such as non-cardiac chest pain, an observation that is further supported by more recent studies [169, 170].

A meta-analysis of studies that used a trial of acid suppression for diagnosing GERD systematically and quantifi-ably evaluated all published studies prior to 2004 and concluded that “successful short-term treatment with a PPI in patients suspected of having GERD does not confidently establish the diagnosis, when GERD is defined by currently accepted reference standards” [171]. In summary, these data indicate that a therapeutic trial of a PPI for 1-2 weeks may be a reasonably useful clinical tool but it is by no means a gold-standard test for the diagnosis of GERD. The advantages of this approach include simplicity, non-invasiveness, ease of prescription and consumption, toler-ability, and savings in terms of direct costs and time lost by the patient, but it does not demonstrate optimal sensitivity or specificity. A positive therapeutic trial may also predict longer term therapeutic response, but data confirming this notion are limited. These studies also support the notion that a symptom-based treatment is reasonable for most patients with reflux disease without a specific diagnosis. Perhaps the greatest value of this test lies in determining that GERD is not likely to be the cause of a given patient’s symptoms (high negative predictive value) when no response to high-dose PPI is achieved.

Treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease

Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux are common and have a significant adverse impact on QOL. The costs of disease include both drug acquisition costs and indirect costs such as testing, physician visits and time off work. Because of the difficulty in making a definitive diagnosis of GERD through diagnostic investigations, the physician must make a presumptive diagnosis and initiate a management plan. The goals of therapy are to provide adequate symptom relief, heal esophagitis and prevent complications. Since initial studies in GERD have focused on mucosal healing; healing of erosive esophagitis will be discussed first, followed by discussions on NERD, and finally on symptomatic treatments in the uninvestigated patient.

Acid suppression therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease

While transient relaxations of the LES and defective basal LES tone are thought to be the primary pathophysi-ological determinants of reflux, symptoms and damage arising from the esophagus are the result of acidic reflux as a consequence of these and other physiological perturbations [43]. Thus, the focus of treatment has been on acid suppression.

Acid secretion and/or gastric pH can be affected by various drugs. Antimuscarinic agents are weak inhibitors of the parietal cell M3 cholinergic receptors, and their clinical use is limited by their anticholinergic side effects. H2-receptor antagonists (H2-RAs) inhibit parietal cell histamine receptors; thus acid inhibition can be largely overcome by stimulation of gastrin and cholinergic receptors, as occurs when food is eaten [172]. Tolerance or tachyphylaxis to H2-RAs develops rapidly and reduces their efficacy with continued use over time [173]. PPIs provide the most potent acid inhibition through covalent binding to the H+, K+-ATPase (acid or proton pump) located in the secretory canaliculus of the parietal cell. Inhibiting the proton pump, which is the final common pathway of acid secretion, diminishes acid secretion to all known stimuli. Despite short serum half-lives, the PPIs have a longer duration of pharmacological action owing to the dependence of acid secretion recovery on the rate of synthesis of new proton pumps by the parietal cell.

Studies of intragastric acidity have been used to assess the degree and duration of acid inhibition with anti-secretary drugs [174, 175]. These studies have confirmed that PPIs are far superior to H2-RAs in their ability to suppress food stimulated, daytime and total 24-hour acid secretion. Bell et al. [174] have shown, by meta-analysis, that the healing rate of erosive esophagitis correlated directly with the duration of gastric acid suppression over a 24-hour period. The primary determinants of healing were the duration of antisecretory treatment, the degree of acid suppression and the duration of acid suppression over the 24-hour period. There was also a highly significant correlation between the time that the pH in the esophagus was above 4 and the ability to heal erosive esophagitis. The authors concluded that if intragastric acidity could be maintained above a mean pH of 4 for 20–22 hours of the day, 90% of patients with erosive esophagitis would be healed by eight weeks. Thus, the superiority of PPIs over H2-RAs was predicted prior to the performance of clinical trials based on their pharmacologic ability to achieve more effective suppression of acid secretion.

Lifestyle modifications

Although lifestyle modifications as a treatment for GERD are frequently recommended, there is little evidence that these are of benefit (Box 2.1). Changing dietary habits and lifestyle modifications are generally considered useful by physicians [176,177]. However, when patients were asked about advice they had received from physicians, lifestyle changes were only modestly recommended [178]. If a patient is under the age of 50, and has no serious “alarm symptoms” such as unexplained weight loss, dysphagia or hematemesis, it is reasonable to start empirical therapy [9, 163] as the most cost-effective approach [179].

One study assessed patients with 24-hour esophageal pH testing and found no difference in lifestyle alteration and anxiety between those with positive and negative pH profiles [180]. However, the data that white wine (vs red wine) induces reflux is reasonably robust [181, 182]. There are several mechanisms identified, including reduced LES pressure [182], disturbed esophageal clearance due to increased simultaneous contractions and failed peristalsis [183, 184]. The most recently identified mechanism is the occurrence of repeated reflux events into the esophagus when pH is still acidic from a previous reflux episode, the so-called “re-reflux” phenomenon [185]. Although caffeine itself is thought to be associated with reflux, one study has proposed that it is something in coffee other than caffeine that is responsible [186]. Smoking is also often implicated (Box 2.1) but results concerning its role are controversial. One 24-hour pH study has shown an association with smoking [186] while another has not [187]. Vigorous exercise has also been implicated as exacerbating reflux, with emphasis on running [188–193], but with evidence also for weightlifting and cycling [189, 193]. Thus, there is some rationale for “mother’s advice” not to exercise right after eating. In one study ranitidine 300 mg, given one hour before running, reduced esophageal acid exposure [192]. While there is some evidence that elevating the head of the bed is beneficial, not all investigators agree as the effectiveness has been studied using esophageal acid exposure (which is improved but not normalized) and not symptoms as an outcome [194]. Lastly, the effect of posture is interesting, as more acid reflux seems to occur in the right lateral position. Thus the left lateral position is recommended for sleeping [195–197]. Meining and Classen reviewed the efficacy of lifestyle modifications as a treatment for GERD in detail and determined that for many of the recommendations, the data are conflicting, weak and, at best, equivocally supportive [198]. A recent systematic review investigating the effect of lifestyle modifications on GERD found that most were not evidence based and had little to recommend their routine use [199].

BOX 2.1 Recommended lifestyle modifications in gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Avoid precipitating foods and drinks: fat [200, 201] (two studies found no effect of fat [202, 203], another found no effect of caloric density [204]), chocolate [205, 206], peppermint [207], spices [208], raw onions [209], carbonated beverages [198, 210], caffeine [4, 185, 211–213], coffee [185], orange juice and tomato drink [210, 214]

- Avoid alcohol [4, 210, 215–217]

- Avoid cigarette smoking [4, 186, 216–218]

- Avoid large meals and gastric distension [44, 219]

- Avoid lying down within 3–4 hours of a meal [220]

- Aggravating factors to be avoided: posture [220], physical exertion especially running [188, 189], weightlifting and cycling [189, 193]

- Raising the head of the bed may have some efficacy [220–223]

- Sleeping on the left lateral position reduces reflux [195–197]

- Avoid tight clothes [4]

- Obesity may be a risk factor [4, 22, 216–224], weight reduction helps symptoms [225], weight reduction does not help [226, 227], Roux-en-Y gastric bypass may benefit [224]

- Avoid certain drugs if possible: β-blockers, anticholinergics including certain antidepressants, theophylline, calcium antagonists, nitrates

In summary, these data do not allow one to recommend lifestyle modifications as a therapy for GERD, although some of the modifications are known to positively affect health in other ways (smoking cessation, weight loss, etc.) and can be recommended on that basis alone.

Placebo response rates

Because healing of moderate to severe esophagitis with placebo therapy occurs in about 28% of patients [13, 228], the use of placebo controls has been important, especially for the less effective drugs, such as H2-RAs and prokinetics. Additionally, the symptomatic placebo response rate ranges from 37-64%, further underscoring the need for placebo controls in less effective therapies for GERD [229]. For PPIs, the therapeutic gain is so large that placebo-controlled trials are less necessary, although they remain useful [13].

Antacids and alginate

A small randomized placebo-controlled trial of Maalox TC at a full dose of 15 ml seven times daily for four weeks in 32 GERD patients showed no significant symptom relief [230]. Other trials have reported marginal if any benefit of antacids and alginates over placebo, and antacids do not heal esophagitis [231-233]. A1d However, a recent meta-analysis concluded that compared with the placebo response the relative benefit increase was up to 60% with alginate/antacid combinations, and 11% with antacids [229].

In an uncontrolled study of patients with grade I to III esophagitis healed with either an H2-RA or omeprazole, patients were given alginate for symptomatic maintenance treatment [234]. At six months, 76% were in remission. Those with more severe baseline esophagitis relapsed more frequently. In a randomized controlled trial, sodium alginate 10 ml four times daily was slightly more effective than cisapride 5mg four times daily for reducing both symptoms measured on a visual analog scale (0-100) (alginate 29 ± 22, cisapride 35 ± 25, p = 0.01) and the number of reflux episodes in a four-week period (alginate 2 ± 2, cisapride 3±4, p = 0.001) [235]. Conservative symptomatic therapy with alginate may be useful in some patients. A1d

Collings et al. [236] recently demonstrated that a calcium carbonate gum decreased heartburn and intraesophageal acidity more than chewable antacids, with effects that lasted for a couple of hours. This observation suggests that such a gum may be useful for intermittent therapy, possibly because of an effect on salivation.

In summary, there are sufficient data supporting a recommendation for antacids as a short-term treatment for symptomatic heartburn; alginate/antacid combinations appear to be superior to antacid use alone.

Prokinetic drugs

In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, metoclopramide and domperidone did not improve esophageal motility, duration of acid exposure or esophageal clearance, although both agents significantly increased LES pressure [237]. Cisapride is the only prokinetic drug that increases both esophageal clearance and enhances LES tone [238, 239]. However, one study provided evidence that cisapride increased acid reflux in comparison with omeprazole and famotidine [240].

Placebo-controlled trials show marginal benefit for cisapride in healing esophagitis and improving symptoms [239, 241–243]. A1d For mild grades of esophagitis, cisapride has been demonstrated to be as effective as H2-RA for healing and symptom relief with comparable tolerability [243–248]. However, this drug requires prolonged use for up to 12 weeks before clinical benefit is seen [242, 243, 245, 247, 249–251].

In one randomized trial in patients with milder GERD, omeprazole 10 or 20 mg daily was significantly more effective than cisapride 10mg four times daily for relief of heartburn, regurgitation and epigastric pain [104]. This and other studies suggest that for symptomatic GERD, the degree of acid suppression is a more important determinant of symptom relief than prokinetic activity. A1d

In healing grades I and II esophagitis, adding cisapride to omeprazole did not significantly increase efficacy over omeprazole alone [252]. In another study of healing grades II and III esophagitis, cisapride 20 mg twice daily added to pantoprazole 40 mg once daily did not improve healing over pantoprazole alone [253]. Thus, these two studies provide strong evidence that the addition of cisapride does not add any clinical benefit to treating with PPIs alone. A1d

Cisapride has demonstrated only modest benefit for maintenance therapy for mild esophagitis [251, 252, 254, 255]. However, in patients with more severe erosive esophagitis initially healed with antisecretory therapy, cisapride was not effective for maintenance treatment [243, 245, 256, 257] and was not more effective than placebo [258]. A1d

The recent Cochrane meta-analysis concluded that there was a paucity of evidence on prokinetic therapy, with no substantive evidence that it is superior to placebo [259]. Cisapride has also been associated with the development of serious cardiac arrhythmias including torsades de pointes, when used with other drugs that inhibit cytochrome P450 3A4. These include fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, erythromycin, clarithromycin, ritonavir, indinavir, nefazodone, tricyclic antidepressants and certain tetracyclic antidepressants, certain antipsychotics, astemizole, terfenadine, and class IA and III anti-arrhythmics [260]. Thus, cisapride is not recommended for the treatment of GERD because its potential for producing significant adverse events is greater than that for other more effective agents, and in many countries the drug has now been withdrawn.

In summary, there are insufficient data to recommend the use of cisapride in the treatment of GERD.

Sucralfate in gastroesophageal reflux disease

For grade I—III GERD, there have been four small, randomized trials of sucralfate 1 g four times daily compared with standard dose H2-RA, none of which demonstrated any significant differences with respect to symptom resolution and healing [261–264]. However, none of these studies showed very large benefits from either intervention, with low rates of heartburn relief (34–62%) and healing (31–64%). Combining sucralfate and cimetidine was not better than monotherapy with either drug [265, 266]. The meta-analysis of randomized trials for grade II–IV esophagitis performed by Chiba et al. yielded a pooled value for healing of 39.2% for sucralfate compared with 28% for placebo [13]. However, the 95% CI was wide (3.6 to 74.8%). A1c

In a six-month study of grade I–II GERD, sucralfate was more effective than placebo for preventing relapse (sucralfate 31%, placebo 65%; ARR 34%, NNT 3, p < 0.001) [267]. A1d

It is interesting that sucralfate, which does not lower acid output, reduce esophageal acid exposure or improve esophageal transit time [268] has any efficacy given our understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition. The adverse effect of constipation, the need for four times daily dosing and the modest observed benefit make sucralfate a less than optimal GERD treatment choice for most patients.

In summary, there are insufficient data to support a recommendation for the use of sucralfate in the treatment of GERD.

H2-receptor antagonists

H2-RAs are not optimally effective in the treatment of GERD but still maintain a role in symptomatic therapy and are discussed here somewhat briefly.

Intermittent/on-demand therapy for heartburn relief

Acid suppressive therapy with H2-RAs has been the mainstay of treatment for acid-related disorders and in many countries these agents are available for over-the-counter (OTC) use [269]. This availability permits intermittent, on demand use by the patient. A blinded crossover trial of famotidine 5,10 and 20 mg versus placebo showed that all famotidine doses were more effective than placebo for the prevention of meal-induced heartburn and other dyspeptic symptoms [270]. This study established that heartburn severity peaked 1–2 hours after a meal. Thus, a small dose of H2-RA taken before eating is useful to reduce GERD symptoms induced by meals.

A unique formulation of a readily dissolving famotidine wafer (20 mg) was compared with standard dose (150 mg) ranitidine [271]. With both treatments, about half the patients had some symptom relief within three hours. A similar randomized trial found trivial but statistically significant differences between ranitidine and famotidine for time to adequate symptom relief (ranitidine 15 minutes, famotidine 18.5 minutes, p = 0.005) and for the proportion of patients with symptom relief at one hour (ranitidine 92%, famotidine 84%; p = 0.02) [272].

A recent meta-analysis of OTC medications determined from ten trials, yielded a relative benefit increase of up to 41% with H2-RAs compared to placebo [229]. Thus, for mild reflux symptoms, use of H2-RA on an as needed basis remains a useful therapy for GERD.

High dose H2-receptor antagonists

While standard doses of H2-RAs heal more severe, grade II to IV esophagitis in about 52% of patients [13], higher doses of H2-RA (150–300 mg four times daily) are more effective, healing 74–80% of patients in 12 weeks, under conditions in which the healing rate with placebo is 40–58% [273, 274]. Silver et al. [275] compared regimens of ranitidine 300 mg twice daily and 150mg four times daily for treatment of erosive esophagitis. At 12 weeks, the healing proportion observed for the four times daily regimen was 77% and for the twice daily regimen, 66% (absolute risk reduction (ARR) 11%, number needed to treat (NNT) 9). Ranitidine 150mg four times daily was superior to standard dose (150 mg twice daily) ranitidine or cimetidine (800 mg twice daily) in patients with erosive esophagitis [276]. In another randomized trial in patients with erosive esophagitis [277], with ranitidine 150 mg twice daily the proportion of patients healed was 54% at eight weeks compared with 75% with 300 mg four times daily (ARR 21 %, NNT 5). A1 d Famotidine is pharmacologically more potent than ranitidine and a large dose of 40 mg twice daily was superior to standard dose 20 mg twice daily or ranitidine 150 mg twice daily in patients with erosive or worse esophagitis [278]. A1d These data suggest that standard dose H2-RAs can be effective in GERD symptom relief, but higher doses are necessary for healing and maintenance of healing of esophagitis.

More complete data on oesophagitis healing with H2-RAs is found in the recently updated Cochrane Review [259], where there was a statistically significant benefit of H2-RAs compared to placebo.

In summary, these data indicate that H2-RAs have a limited but measurable effect in treating GERD, and symptoms respond better than healing to treatment.

Erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease

Meta-analysis of healing and symptom relief with proton-pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonists

An early meta-analysis of randomized trials of patients with more severe esophagitis (grade II in 61.8%, grade III in 31.7% and grade IV in 6.5%) established the clinical efficacy of PPIs [13]. Subsequent published studies support the conclusions derived from this meta-analysis [259, 279–295]. A1d

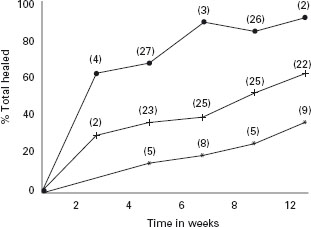

In the meta-analysis [13], the rate of healing, expressed as “percent healed per week”, was significantly superior with PPI therapy compared with H2-RA, particularly early in the course of treatment (weekly healing rate in first two weeks: PPI 32%, H2-RA 15%). The rate of healing slowed with increasing duration of treatment as fewer patients remained unhealed, but PPI remained superior to H2-RA. The overall healing proportions during 12 weeks, using pooled results irrespective of dose and duration were: PPI 84% (95% CI: 79 to 88), H2-RA 52% (95% CI: 47 to 57), sucralfate 39% (95% CI: 4 to 75) and placebo 28% (95% CI: 19 to 37). These data were used to plot rate of healing against time on a “healing time curve” (Figure 2.2). By the end of the second week, PPI had healed 63.4 ± 6.6% of patients, while H2-RA required 12 weeks to achieve healing in a similar proportion of patients (60.2 ± 5.9%). Linear regression analysis of individual study results showed that PPI heal at an overall rate of 11.7% per week (95% CI: 10.7 to 12.6), twice as rapidly as H2-RA (5.9% per week, 95% CI: 5.5 to 6.3) and four times more rapidly than placebo (2.9, 95% CI: 2.4 to 3.4).

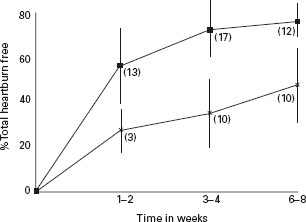

Heartburn was present in all but 3.8% (95% CI: 2.1 to 5.5) of patients at baseline. Overall, heartburn relief was seen in 77.4 ± 10.4% of patients treated with PPI and in 47.6 ± 15.5% treated with H2-RA. Data for heartburn relief were plotted against time to create a “symptom relief time curve” (Figure 2.3). Linear regression analysis of the data yielded an overall heartburn relief rate of 11.5% per week for PPI (95% CI: 9.9 to 13.0) and 6.4% per week for H2-RA (95% CI: 5.4 to 7.4).

Figure 2.2 Healing-time curve expressed as the mean total healing for each drug class per evaluation time in weeks. By week 4, PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) heal more patients than any other drug class, even after a much longer duration of treatment (12 weeks), implying a substantial therapeutic gain despite the fact that all drug classes achieve higher healing with longer durations of therapy. The number of studies is shown in parentheses. •: PPI; +: H2-RA, *: placebo. Reproduced with permission from Chiba N et al. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1798–1810 [13].

Figure 2.3 Symptom relief-time curve expressed as the mean total heartburn relief for each drug class corrected for patients free of heartburn at baseline at 1–2, 3–4, and 6–8 weeks. By week 2, more patients treated with PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) are asymptomatic compared with H2-RA (H2-receptor antagonists) even after a much longer duration of treatment (eight weeks), implying a substantial therapeutic gain despite the fact that both drug classes achieve greater symptom relief with longer durations of treatment. The number of studies is shown in parentheses.  : PPI; x: H2-RA. Reproduced with permission from Chiba N etal. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1798–1810 [13].

: PPI; x: H2-RA. Reproduced with permission from Chiba N etal. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1798–1810 [13].

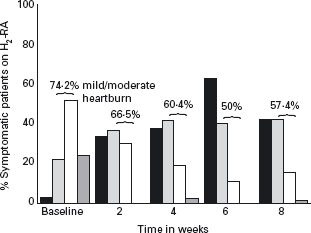

Figure 2.4 Shift in heartburn relief with H2-RAs (H2 receptor antagonists). From studies using a symptom scale of none, mild, moderate, or severe, the shift in symptom severity with duration of treatment can be observed. With H2-RAs, although there is an increase in the number of patients completely heartburn free, at the end of the study, more than half of the patients still have mild to moderate symptoms: none ( ); mild (

); mild ( ); moderate (□); severe (

); moderate (□); severe ( ). Reproduced with permission from Chiba N et al. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1798–1810 [13].

). Reproduced with permission from Chiba N et al. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1798–1810 [13].

Figure 2.5 Shift in heartburn relief with PPIs. PPIs (omeprazole)-treated patients have a dramatic shift in the number of patients completely symptom free, particularly early in-treatment, and at the end of the study, very few patients have any residual heartburn in contrast to patients treated with H2-RAs: none ( ); mild

); mild  ; moderate (□); severe

; moderate (□); severe  . Reproduced with permission from Chiba N et al. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1798–1810 [13].

. Reproduced with permission from Chiba N et al. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1798–1810 [13].

Some studies measured heartburn in categories of none, mild, moderate or severe and reported the shift in heartburn relief with treatment (Figures 2.4 and 2.5). The proportion of patients with residual mild to moderate symptoms after eight weeks of therapy was 11.1% for PPI and 57.4% for H2-RAs.

This meta-analysis provided evidence that PPI are significantly better than H2-RA for both healing esophagitis and relieving symptoms in patients with moderately severe esophagitis. There was also evidence in one RCT that PPI therapy is effective for healing persistent grade II–IV esophagitis after treatment failure with 12 weeks standard dose H2-RA [296]. Ald

Other more recent Cochrane meta-analyses have demonstrated similar findings, with PPIs being superior to H2-RAs in healing and maintenance of healing of esophagitis [259, 297]. These data support a recommendation for the use of PPIs rather than H2-RAs for the healing and maintenance of healing of esophagitis, as well as for heartburn relief.

Differences in efficacy between proton pump inhibitors

There are now five proton-pump inhibitors available in North America. These are omeprazole, lansoprazole, pan-toprazole, rabeprazole and esomeprazole.

For symptom relief, esomeprazole has been shown to be more rapidly effective than omeprazole [32, 290], lansoprazole [284, 298] and pantoprazole [299]. In other studies, lansoprazole was more rapidly effective than omeprazole [33] and pantoprazole non-inferior to esomeprazole [300]. However, differences in symptom relief were no longer apparent at the end of these studies [279, 287, 301, 302]. In another study, omeprazole and pantoprazole were found to be equivalent with each other but not with lansoprazole regarding rapidity of symptom relief [303]. Similar results were found in a comparison of rabeprazole and omeprazole [294]. Low, half-doses of PPIs compared with standard doses were not found to be as effective for healing esophagitis or for symptom relief [146, 279]. However, for maintenance therapy some data suggest that low dose PPIs are as effective as standard doses [37, 304, 305]. While there were small differences between overall study results, the data from these studies were insufficient to establish the superiority of any one drug over all others [306].

Vakil and Fennerty recently carried out a careful systematic review of randomized controlled trials that directly compared PPIs to determine whether there is a difference in clinical outcomes between any of these agents [306]. They restricted this review to more recent (1998–2002), better quality trials. They found similar healing rates for the following comparisons:

- lansoprazole 30 mg daily compared with omeprazole 20mg [301] or 40mg [280], or pantoprazole 40mg daily [291]

- pantoprazole 40 mg [307] or rabeprazole 20 mg [281,289] compared with omeprazole 20 mg daily A1c

They found that for esophagitis healing, esomeprazole was superior to omeprazole and lansoprazole [32, 284, 290]. Earlier randomized trials comparing two different PPIs (lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole and rabe-prazole) had also failed to show a difference in healing rates with drugs used at standard recommended doses [27, 31, 279, 280, 287, 301, 307, 308]. A1d

Two other meta-analyses also have shown that esome-prazole was superior to omeprazole and that other PPIs did not produce higher healing rates than omeprazole [309–311]. A1c Another review concluded that lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole were comparable with omeprazole in terms of heartburn control, healing rates and relapse rates [312]. Systematic reviews of data from randomized trials performed up to 2005 that compared esome-prazole to other PPIs showed that esomeprazole was more effective than omeprazole, lansoprazole and pantoprazole for healing esophagitis at four and eight weeks, but there is still no direct comparative trial of esomeprazole against rabeprazole [311,313]. Esomeprazole 40mg daily was more effective for healing the more severe LA grades C and D esophagitis in randomized trials in which it was compared with omeprazole 20mg daily [32, 290, 313], lansoprazole 30mg [284, 298, 313] or pantoprazole [299, 313, 314]. A1d One randomized trial that included only 284 patients but was otherwise similar in design to the trial that included 5241 patients showed no difference between esomeprazole 40 mg and lansoprazole 30 mg for healing of erosive (or more severe) esophagitis in four or eight weeks; the smaller trial may have lacked statistical power [285]. A1c Subsequently, another study showed esomeprazole superior to pantoprazole [314].

Esomeprazole is the first PPI shown to be more effective than any other PPI; all other direct comparisons have shown that healing rates are essentially the same for all agents in this class [285]. However, in elderly patients over age 65 there may be some differences [315]. In a relatively small randomized trial, Pilotto and colleagues compared standard dose omeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and lansoprazole for healing of esophagitis using the outdated Savary-Miller classification [315]. They determined that at eight weeks, pantoprazole and rabeprazole were significantly more effective than omeprazole for healing esophagitis and were also more effective than omeprazole or lansoprazole for relieving symptoms. The authors were unable to provide an adequate explanation for apparent differences in response in the elderly population [315].