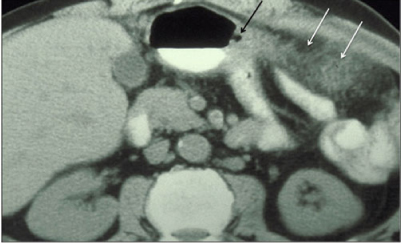

Fig. 1

Transaxial computed tomography (CT) image demonstrates the gastrohepatic ligament (GHL), seen as a fatty plane interposed between the lesser curvature of the stomach and the lobe of the liver. The GHL contains the left gastric artery (arrow), the left gastric vein (coronary vein), and associated lymphatics

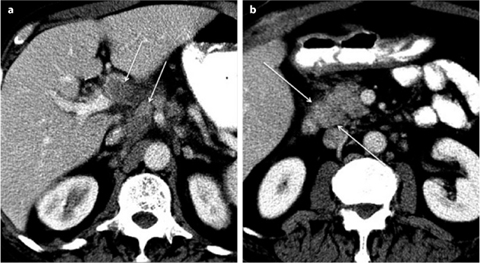

Gastric disease commonly spreads to the liver and hepatic disease commonly spreads to the stomach via the gastrohepatic ligament. An important feature is that the subperitoneal areolar tissue within the ligament is continuous with the perivascular fibrous capsule of the liver (Glisson capsule). This feature provides a direct pathway from the gastrohepatic ligament into the liver parenchyma. Gastric disease can spread directly into the left lobe of the liver, and hepatic disease can readily invade the stomach via this pathway, including both neoplastic and inflammatory conditions (Fig. 2). Several types of malignancies are known to spread via lymphatic extension through the gastrohepatic ligament, including gastric and esophageal cancer. Direct invasion through the gastrohepatic ligament can also occur from gastric and esophageal cancer spreading to the liver and hepatoma and cholangiocarcinoma spreading to the stomach.

Fig. 2

Transaxial computed tomography (CT) image demonstrates a heterogenous mass centered in the gastrohepatic ligament (GHL), with invasion of the left hepatic lobe and the stomach (arrow). Prospectively, it was unclear as to the organ of origin, but it proved to be a hepatoma extending through the GHL to involve the stomach

Hepatoduodenal Ligament

The hepatoduodenal ligament is intimately related to the gastrohepatic ligament, as it forms the free edge of the gastrohepatic ligament along its rightward aspect. Together, these structures comprise the lesser omentum. The primary structures of the porta hepatis, including the common bile duct, the hepatic artery, and the portal vein, coexist within the hepatoduodenal ligament. The hepatoduodenal ligament extends from the flexure between the first and second duodenum to the porta hepatis, forming a tent-like structure extending from anterior to posterior as it courses from superior to inferior. Immediately posterior to the ligament is the foramen of Winslow, permitting access to the lesser sac [5]. Unlike nodes within the gastrohepatic ligament, which tend to be smaller than elsewhere in the abdomen, nodes at the base of the hepatoduodenal ligament at the foramen of Winslow (in the portocaval space) have an unusual morphology such that their transverse dimension is greater than their anteroposterior (AP) dimension. Typically, these nodes can be up to 2.0 cm in transverse dimension and up to 1.5 cm in AP dimension and still be normal. Unless these nodes are grossly enlarged, internal pathology can be difficult to recognize but may be suggested by a more spherical shape or central necrosis [6, 7].

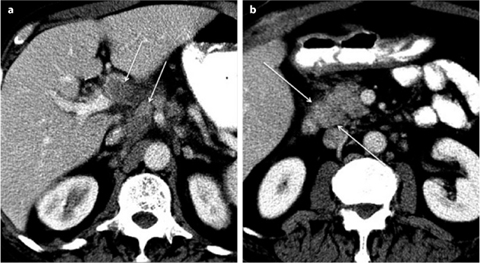

A wide range of neoplastic and inflammatory conditions commonly spread via the hepatoduodenal ligament. Lymphatic extension can occur within the lymphatics in the hepatoduodenal ligament, propagating neoplastic disease in both directions (Fig. 3). Liver or biliary cancer may spread in an antegrade fashion through lymphatics in the hepatoduodenal ligament to deposit in periduodenal and peripancreatic lymph nodes. Conversely, malignant disease in nodes surrounding the superior mesenteric artery, as may occur in the setting of pancreatic and colon cancer, can spread in a retrograde fashion up the lymphatics in the hepatoduodenal ligament to the liver. Direct invasion can also occur through the hepatoduodenal ligament, commonly involving gastric cancer arising in the lesser curvature of the stomach and spreading through the gastrohepatic ligament to the hepatoduodenal ligament and then to peripancreatic and periduodenal lymph nodes. A host of inflammatory conditions also spreads commonly through this ligament, including inflammatory conditions arising within the gall bladder and biliary tree that can spread down the ligament, as well as pancreatitis that can spread up the ligament. Vascular complications related to both neoplastic and inflammatory conditions commonly involve structures within the hepatoduodenal ligament, including the portal vein and hepatic artery. Portal venous thrombosis and hepatic arterial pseudoaneurysms may occur as complications to disease spreading within the hepatoduodenal ligament [1, 5].

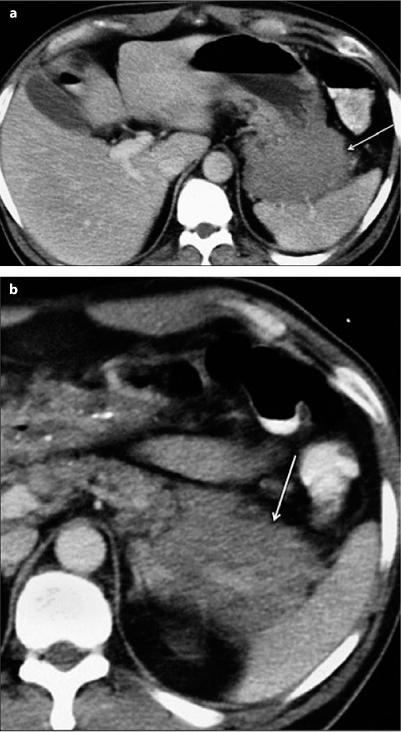

Fig. 3 a, b

Transaxial computed tomography (CT) images through a the porta hepatis and b the uncinate process demonstrate bulky lymphadenopathy (arrows) in the hepatoduodenal ligament (HDL) in a patient with gallbladder carcinoma. Tumor has spread bidirectionally within the HDL proximally (a) and distally to the insertion of the HDL on the second portion of the duodenum (b) (arrows)

Gastrosplenic and Splenorenal Ligaments

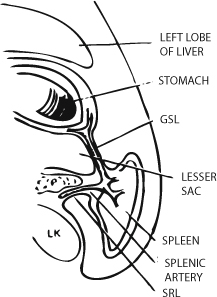

As the gastrohepatic and hepatoduodenal ligament connect the lesser curvature of the stomach to the porta hepatis and the retroperitoneum in the right abdomen, the gastrosplenic and splenorenal ligaments connect the gastric greater curvature to the splenic hilum and the retroperitoneum in the left abdomen (Fig. 4) [8]. The superior third of the gastric greater curvature and the splenic hilum are connected by a rather thin filamentous ligament known as the gastrosplenic ligament. The left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels and associated lymphatics reside within the ligament. Gastric disease commonly propagates to the splenic hilum through this ligament. Once reaching the spleen, both inflammatory and neoplastic disease of the stomach can invade the spleen via this pathway.

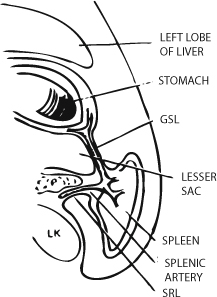

Fig. 4

Gastrosplenic ligament (GSL) and splenorenal ligament (SRL) comprise the left wall of the lesser sac and provide a conduit for the spread of metastatic disease from the greater curvature of the stomach to the retroperitoneum and vice versa. Reprinted from [8] with permission of Springer Science and Business Media

The gastrosplenic ligament is continuous with the splenorenal ligament posteriorly and medially, and thus, gastric disease spreading to the splenic hilum can continue posteriorly to the retroperitoneum. Not uncommonly, disease spreading through the splenorenal ligament can involve the tail of the pancreas and engulf the splenic vasculature (Fig. 5) [9, 10]. Similarly, pancreatic disease, both neoplastic and inflammatory, may spread via the splenorenal ligament to the splenic hilum and continue on through the gastrosplenic ligament to the gastric greater curvature [1].

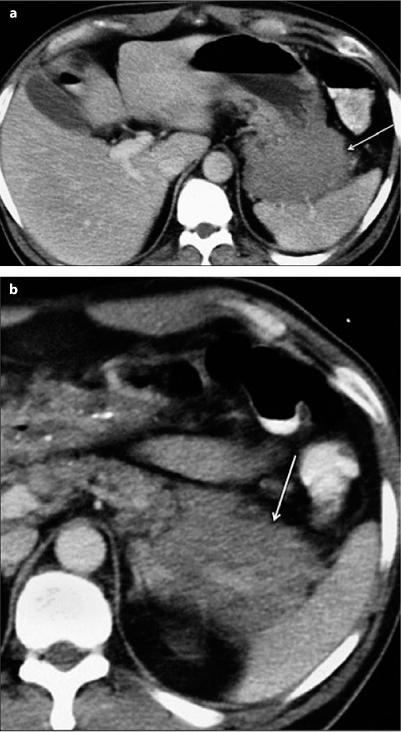

Fig. 5 a, b

Transaxial computed tomography (CT) images through a the gastrosplenic ligament (GSL) and b the splenorenal ligament (SRL) in a patient with lymphoma. Tumor is seen within the GSL, interposed between the gastric greater curvature and the spleen (a), and within the SRL, encasing the splenic vasculature (b) (arrow)

Gastrocolic Ligament

In the midabdomen, the gastrocolic ligament (greater omentum) joins the inferior two thirds of the gastric greater curvature to the transverse colon (Fig. 6) [11]. In concert with the transverse mesocolon, the gastrocolic ligament provides an important conduit of disease between the stomach, transverse colon, and retroperitoneum. The gastrocolic ligament is continuous with the gastrosplenic ligament in the left abdomen, and it ends at the gastroduodenal junction near the hepatoduodenal ligament on the right. In the embryo, the gastrosplenic ligament is a long ligamentous attachment between the stomach and the retroperitoneum that gives rise to the gastrocolic ligament and the transverse mesocolon in the adult. Because the adult gastrocolic ligament results from fusion of the anterior and posterior leaves of the embryonic gastrosplenic ligament, it contains four layers of peritoneum that invest the stomach and, thus, it has a potential space within it that can fill with fluid under certain conditions. On occasion, tense ascites in the lesser sac can dissect open the potential space within the gastrocolic ligament, resulting in a cyst-like appearance within the greater omentum.

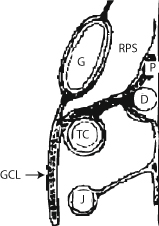

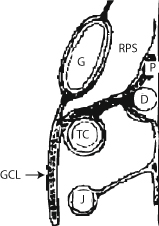

Fig. 6

Gastrocolic ligament (GCL) joins the greater curvature of the stomach (G) to the transverse colon (TC). In concert with the transverse mesocolon, a pathway of disease is formed between retroperitoneal structures such as the pancreas (P) and the duodenum (D) to the anterior aspect of the intraperitoneal cavity. RPS, right peritoneal space, lesser sac; J, jejunum. Modified from [11]

The gastroepiploic vessels and associated lymphatics reside within the gastrocolic ligament and can aid in its identification in the fatty plane that connects the stomach to the transverse colon. The gastrocolic ligament provides an important conduit of both benign and malignant disease from the inferior two thirds of the gastric greater curvature to the transverse colon and vice versa (Fig. 7). Together with the transverse mesocolon, the gastric greater curvature is connected to the retroperitoneum via the gastrocolic ligament and the transverse mesocolon. Thus, disease involving the stomach, transverse colon, and pancreas are interconnected directly by these two structures. In addition, the fatty veil of the greater omentum provides an important nidus for peritoneal metastases, as commonly occur with ovarian, gastric, colon, and pancreatic cancer [12, 13]. Finally, pancreatic tumors that spread by direct invasion locally, or gastric disease spreading to the pancreas via the gastrocolic ligament/transverse mesocolon and/or gastrosplenic/splenorenal ligaments, may encase the splenic vasculature and result in splenic venous compromise, resulting in gastroepiploic collaterals seen within the gastrocolic ligament.