Fistulotomy and Fistulectomy

H. Kessler

T. Weidinger

The goals of fistula surgery are simple: to cure the fistula with the lowest possible recurrence rate, to minimize any alteration of continence, and to achieve a good result in the shortest period of time. To obtain this outcome, a number of principles have to be observed: the primary opening of the track has to be identified and also the relationship of the fistula to the puborectalis muscle; furthermore, the least amount of muscle should be divided to cure the fistula (4). The presence of a discharging opening in the perianal region, which is either persistent or recurrent is an indication for surgery. An anal fistula will rarely heal spontaneously. If left untreated, repeated abscesses with associated morbidity is probable to occur. Although nonoperative methods of therapy have been attempted, it is generally accepted that the only form of treatment affording reliable prospective cure is surgery.

An operation should be recommended unless there are specific medical contraindications to anesthesia. Patients with established compromised anal continence present a relative contraindication because the further division of muscle required when treating the fistula might render the patient totally incontinent. It is important to know whether active Crohn’s disease is present, in which case a very thorough endoscopic investigation and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan would be advisable. Control of active Crohn’s disease should precede repair of an associated anal fistula. Under these circumstances, extensive fistula operations should be avoided.

It is controversial whether fistulotomy or fistulectomy is the more appropriate operative treatment for anal fistulas. There are several reasons, however, to prefer fistulotomy whenever possible. Fistulectomy means the complete removal of the fistulous track and adjacent scar tissue, which results in appreciably larger wounds. There is a larger separation of the ends of the sphincter after fistulectomy, which results in a greater chance of incontinence and a longer healing time. When a fistula crosses the sphincter muscle at a high level like a high transsphincteric or suprasphincteric fistula, there is always concern that division of the muscle below the track will impair continence. In these cases, the advancement rectal flap technique would be appealing with less sphincter muscle to be divided, avoidance of contour defects, less pain due to the absence of a perineal wound and faster healing (3) (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Overview of Recommendations for Surgery in Anal Fistula | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Clinical Assessment

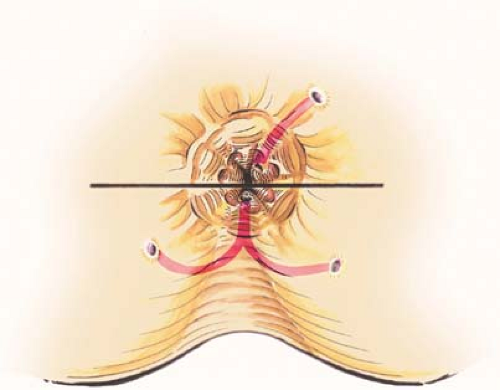

Localization of the internal opening in most cases enables the classification of perianal fistulas. The external opening of an intersphincteric fistula is almost always located near the anal verge, whereas the distance between the external opening of a transsphincteric fistula and the anal verge is several centimeters or more. In the past, Goodsall and Miles described several aspects regarding the relation between the external and the internal openings of perianal fistulas (Fig. 6.1). For many years, Goodsall’s rule has been used in predicting the course of fistulous tracts. In a recent prospective study of 216 consecutive patients (1), Goodsall’s rule was found, however, to be accurate in only 50% of these patients.

Surgical access depends upon accurate assessment, including a full medical history and proctosigmoidoscopy. It is necessary to exclude associated conditions. The classical

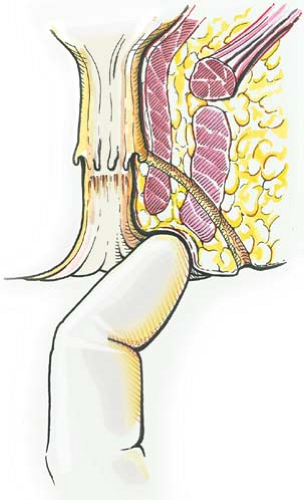

five essentials of clinical assessment include identification of the internal opening, the external opening, the course of the primary track, the presence of secondary extensions, and the presence of other diseases complicating the fistula. The internal opening is the key to the assessment. The relative positions of external and internal openings indicate the likely course of the primary track. Palpable superficial induration suggests a relatively superficial track (Fig. 6.2), whereas supralevator induration suggests a track within the ischiorectal fossa or more likely a secondary extension (Fig. 6.3). The distance of the external opening from the anal verge may help differentiate an intersphincteric from a transsphincteric fistula; the greater the distance, the greater the likelihood of a complex cephalad extension. Exceptions from Goodsall’s rule include anterior openings more than 3 cm from the anal verge, which may be anterior extensions of posterior horseshoe fistulas, or fistulas associated with other diseases, especially Crohn’s disease and cancer.

five essentials of clinical assessment include identification of the internal opening, the external opening, the course of the primary track, the presence of secondary extensions, and the presence of other diseases complicating the fistula. The internal opening is the key to the assessment. The relative positions of external and internal openings indicate the likely course of the primary track. Palpable superficial induration suggests a relatively superficial track (Fig. 6.2), whereas supralevator induration suggests a track within the ischiorectal fossa or more likely a secondary extension (Fig. 6.3). The distance of the external opening from the anal verge may help differentiate an intersphincteric from a transsphincteric fistula; the greater the distance, the greater the likelihood of a complex cephalad extension. Exceptions from Goodsall’s rule include anterior openings more than 3 cm from the anal verge, which may be anterior extensions of posterior horseshoe fistulas, or fistulas associated with other diseases, especially Crohn’s disease and cancer.

The first component of preoperative assessment is to identify the site and level of the primary track. The second component is to determine the presence or absence of any secondary track (9).

Although advocated by some authors, it is questionable whether the internal opening of a perianal fistula can be localized accurately by digital examination. This method of examination is still important, however, since a tender palpable mass in the pelvis may reveal a supralevator abscess. It also provides some information regarding the quality of the anal sphincters by assessing the sphincter tone (10).

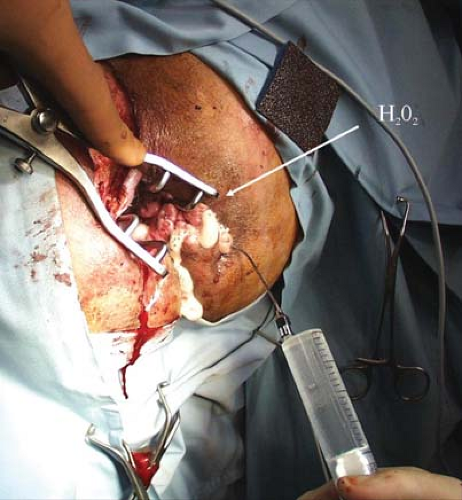

It is essential that the surgeon has an adequate choice of probes available. A soft, blunt-ended copper probe is preferable, which bends easily and does not break. A seton may be tied around its thickened end to thread it through the track if necessary. Probing, however, is not advocated on an outpatient basis, since it can be painful. Furthermore, there is a considerable risk of creating a false passage into the anal canal or into the rectum. It has also been suggested that injection of a diluted solution of methylene blue into the external opening enables the identification of the internal opening of a perianal fistula. A major drawback of this technique is staining of the surrounding

tissues. An alternative is hydrogen peroxide, which does not stain the operative field (10) (Fig. 6.4).

tissues. An alternative is hydrogen peroxide, which does not stain the operative field (10) (Fig. 6.4).

Figure 6.3 Palpation for deep induration originating from supralevatoric extension of a transsphincteric fistula. |

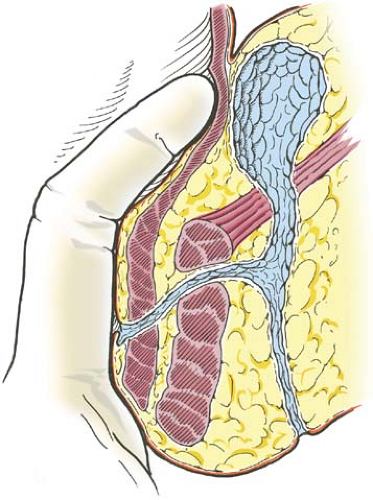

At first glance, any external opening has to be identified (Fig. 6.5). The finger on the skin should feel for the direction of the track using a well-lubricated finger between the external opening and the anal orifice. An indurated track suggests a fairly superficial course: its direction will give a hint for the circumferential location of the internal

opening. Then, the internal opening has to be identified. This is the key to the surgical anatomy. The index finger should be used for feeling any induration within the anal canal. Counterpressure has to be applied on the perianal skin with the thumb. The internal opening is likely to be located at the level of the dentate line. There is often an enlarged papilla in the region of the internal opening and, with experience, the opening itself can be felt in most cases. The level of the internal opening in relation to the puborectalis muscle may be determined by asking the patient to contract the anal sphincter; it may be possible to feel how much functioning muscle would remain if the primary track had to be laid open.

opening. Then, the internal opening has to be identified. This is the key to the surgical anatomy. The index finger should be used for feeling any induration within the anal canal. Counterpressure has to be applied on the perianal skin with the thumb. The internal opening is likely to be located at the level of the dentate line. There is often an enlarged papilla in the region of the internal opening and, with experience, the opening itself can be felt in most cases. The level of the internal opening in relation to the puborectalis muscle may be determined by asking the patient to contract the anal sphincter; it may be possible to feel how much functioning muscle would remain if the primary track had to be laid open.

Supralevator induration is normally a sign of primary track extension. A secondary track most usually arises from a transsphincteric primary track, extending upward to the apex of the ischiorectal fossa, or even through the levators. Alternatively, supralevator induration may arise from an upward extension of an intersphincteric track. Digital examination cannot distinguish between these two possibilities.

Examination under anesthesia should be routinely carried out under general anesthesia immediately before proceeding with surgery. This may identify features that are not easy to determine while the patient is awake. Probes should very rarely be used in the awake patient. Posterior retraction of the dentate line helps expose concealed openings; massage may release a bead of pus. Various agents injected along the track via the external opening have been used to locate the internal opening as described earlier. In most cases, with an anterior external opening, the internal opening will be located at the same circumferential point. Careful probing can delineate primary and secondary tracks. If the internal and external openings are easily detected, but the probe cannot easily traverse the path of the track, there may be a high extension. In this circumstance, a probe passed via each opening may then delineate the primary track. Persistence of granulation tissue after curettage indicates a continuing track (9).

Assessment by Imaging Techniques

For many years, fistulography was the only imaging technique for the preoperative assessment of perianal fistulas, including the localization of their internal opening. However, there are only few data regarding its accuracy. Based on limited and rather conflicting data, it is impossible to assess the exact role of fistulography in the preoperative imaging of perianal fistulas (10). Meanwhile, fistulography has been surpassed by endosonography and MRI. Advantages of both techniques are the direct visualization of the fistulous track and the imaging of the anal sphincters. Endosonography offers a 360° axial image. Installation of hydrogen peroxide improves the accuracy of the procedure. Most reports show an accuracy between 50% and 70% regarding the detection of the primary fistulous track (10). Besides, the presence of sepsis in the intersphincteric plane and sometimes in the deep postanal space may be detected. In addition, defects in the

sphincters are identified, which may influence the management of anterior fistulas in women. Although some transsphincteric fistulas can be visualized, the perineal component of anal fistulas cannot be seen in most patients. Anal ultrasonography therefore gives more information about the sphincters than the anatomy of the fistula.

sphincters are identified, which may influence the management of anterior fistulas in women. Although some transsphincteric fistulas can be visualized, the perineal component of anal fistulas cannot be seen in most patients. Anal ultrasonography therefore gives more information about the sphincters than the anatomy of the fistula.

MRI is now regarded as the investigation of choice to define complex anorectal sepsis and fistulas. In the literature (5), it is claimed to provide 100% accuracy in defining the presence of a fistula and the site of extensions and is 85% accurate in locating the anatomy of the primary track. MRI scanning has proven particularly useful in patients with doubtful fistulas. It correctly identifies sepsis without fistulas, scar tissue alone, and blind tracks with no internal opening, thereby preventing unnecessary surgical exploration. MRI is also particularly useful in defining horseshoe fistulas but may miss internal openings because imaging of the intersphincteric space is not as good as with anal ultrasound. It may be useful to involve a single specialized radiologist to deal with this topic. Despite its excellent accuracy, MRI of perianal fistulas has several drawbacks as it is rather expensive and time-consuming and cannot be performed in patients with a metal implant or a pacemaker.

Principles

The principles of treatment are quite simple: to define the anatomy of the fistula track and its secondary extensions, to drain any coexisting pus, and then to provide definitive treatment by laying open, excision, or placement of a seton through the fistula track if it enters below the anorectal ring. If, on the other hand, the fistula lies outside the somatic cylinder and above the anorectal ring, the fistula track should be excised or defined with a seton and the defect in the gut may be closed.

Intersphincteric Fistulas

Intersphincteric fistulas can be readily treated with minimal morbidity or complication by merely laying open the fistula track into the anal canal. Only the distal part of the internal anal sphincter is divided. Subsequent incontinence for solid stool is rare, since the external anal sphincter remains intact. However, the permanent defect in the internal anal sphincter might result in soiling and incontinence for gas or liquid stool. The reported incidence for these “minor” continence disturbances varies between 8% and 50% (10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree