12 Female Urethral Reconstruction

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

Urethral reconstruction is most commonly performed to treat urethral stricture disease, urethral prolapse, urethral ablation, and urethrovaginal fistula. Female urethral stricture disease is relatively rare and can be caused by radiation exposure, inflammatory processes, difficult catheterization with subsequent fibrosis, prior dilation, urethral surgery, or trauma. Rarely strictures may be a consequence of estrogen deficiency. Urethral ablation usually results from urethral trauma, from long-term use of an indwelling urethral catheter (usually in a patient with decreased or absent sensation), or as a complication of urethral surgery.

Distal Urethral Reconstruction

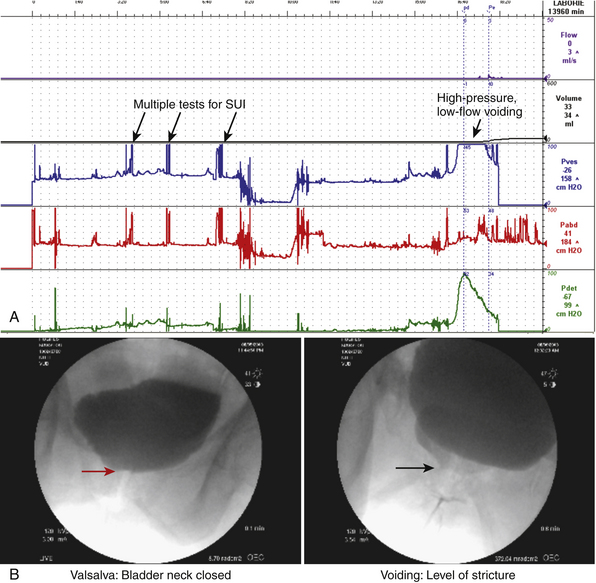

Stenosis or stricture of the distal urethra in women often presents with lower urinary tract voiding and storage symptoms (decreased force of stream, prolonged or incomplete emptying, and frequency and/or urgency). Distal stricture can be seen following traumatic urethral instrumentation and endoscopic procedures or radiation therapy to the pelvis or vulva for gynecological malignancy; it also occurs in postmenopausal women with significant vaginal atrophy from estrogen deficiency or with vulvar dystrophy. The diagnosis of a functional urethral stricture can be made using a combination of patient history (symptoms), physical examination findings (obvious scarring and/or the inability to pass a urethral catheter), endoscopy, radiography (voiding cystourethrography), and urine flow evaluation (decreased or abnormal flow). In cases of uncertainty videourodynamic testing can be helpful (Fig. 12-1). The two most common types of urethral reconstruction that we perform are distal urethrectomy with advancement meatoplasty, used for very distal strictures (generally involving the distal 1 cm of the urethra), and Blandy urethroplasty, used for lesions up to 1.5 to 2.0 cm proximal to the urethral meatus.

Surgical Technique for Distal Urethrectomy With Advancement Meatoplasty

Meatotomy can be performed to treat distal stenosis by simple ventral incision of the meatus and suturing of the cut end of the meatus to the vaginal wall. However, in our experience, circumferential distal urethrectomy and advancement meatoplasty works best for distal strictures and urethral prolapse. The technique can be applied to meatal stenosis and strictures within approximately 7.5 mm of the meatus (Video 12-1).

1. The extent of the stricture is identified. If desired, interrupted absorbable sutures can be placed in the more proximal, healthy urethral mucosa (at least 2 mm proximal to the strictured segment) at the 6 and 12 o’clock positions so that the mucosa does not retract inward. A nasal speculum can assist in identifying healthy mucosa. When the urethral meatus is severely narrowed, an initial ventral incision may be necessary to determine the extent of the stricture.

2. A circumferential incision is made around the urethra at the mucosal-epithelial junction, and the urethra is dissected off the periurethral fascia for the extent of the stricture.

3. The distal urethra and meatus are excised.

4. Healthy urethral mucosa is then advanced and circumferentially sutured to the vaginal epithelium in an interrupted fashion with 4-0 polyglycolic acid (PGA)* or poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl) sutures. This creates a neomeatus with well-vascularized, nondiseased mucosa.

5. Depending on the degree of reconstruction, a urethral catheter may be left in place for 1 to 3 days postoperatively. This is particularly useful because postoperative swelling may cause urinary retention.

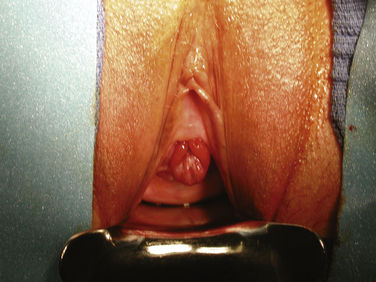

In adult women urethral prolapse can occur as a result of habitual straining to defecate or void but sometimes may have no clear cause. Urethral prolapse is characterized by a circumferential protrusion of the urethral mucosa (Fig. 12-2); in contrast, an inflammatory urethral caruncle usually occupies one or two quadrants of the urethra (Fig. 12-3). Urethral prolapse often is asymptomatic and requires no treatment. However, sometimes it can bleed or cause obstructive voiding symptoms requiring intervention. Surgery for urethral prolapse is similar to the procedure described earlier for distal urethrectomy with advancement meatatoplasty, except that the prolapsed urethra needs to be mobilized only to the mucosal-epithelial junction. After the prolapsed urethra is excised, a circumferential reapproximation as described previously is performed at the site of the original urethral meatus. In the case of a urethral caruncle, simple excision of the inflammatory mass with reapproximation of the cut mucosal edge to the epithelium is usually all that is necessary.

Figure 12-3 Urethral caruncle. The inflammatory tissue occupies the left side of the urethral meatus.

Case #1

View Video 12-1

View Video 12-1

A 59-year-old women presents with decreased force of stream and incomplete bladder emptying. She has had these symptoms for about 5 years and was previously diagnosed with urethral meatal stenosis (etiology unclear). She has been managed with periodic urethral dilations and topical estrogen. Initially, dilations relieved symptoms for about 6 months, but now they only last about 3 weeks. She is not interested in doing self-catheterization to keep the stricture open. Cystourethroscopy shows a scarred distal urethra (about 0.5 cm), and the rest appears normal. She elected to have definitive treatment with excision of the scarred distal urethra and an advancement meatoplasty, which is feasible due to the distal location of the stricture (see Video 12-1).

Surgical Technique for Blandy Urethroplasty

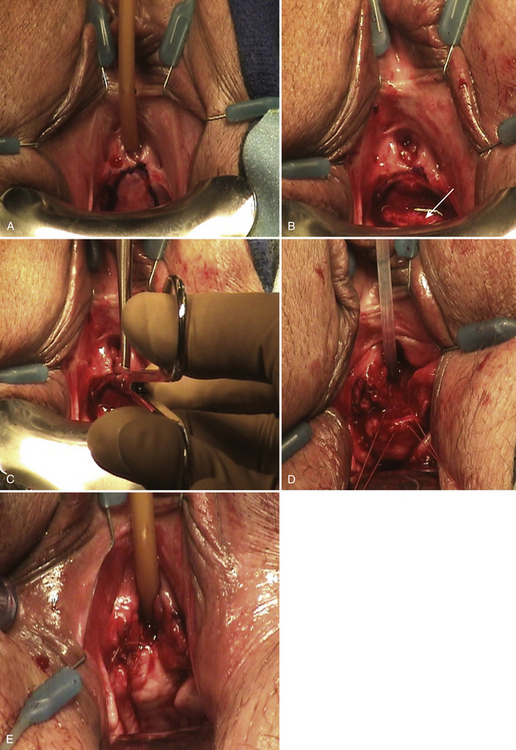

For strictures longer than 1 cm and those that originate in the mid-distal urethra, we prefer to perform Blandy urethroplasty. This procedure, which uses a proximally based vaginal pedicle flap, was originally described by Blandy but not reported in the literature. A description was subsequently published by Bath Schwender et al. The procedure (Video 12-2) is applicable to strictures that extend up to 2 cm from the urethral meatus. Blandy urethroplasty re-creates the ventral portion of the urethral meatus and replaces the distal ventral urethra with a flap of vaginal wall. The surgical steps are as follows:

1. The urethra is catheterized with a 14F catheter if possible, but a smaller catheter may be used if necessary.

2. An inverted-U incision is made in the anterior vaginal wall with the apex of the U at the urethral meatus (Fig. 12-4, A).

3. With sharp dissection, a proximally based vaginal flap is raised that is the approximate length of the stricture (2 to 3 cm) (see Fig. 12-4, B).

4. The proximal limit of the stricture is identified, which can be done by inserting a nasal speculum into the urethral meatus. The stricture is incised ventrally at the 6 o’clock position (see Fig. 12-4, C). Cystoscopy can also be used to aid in determining the limit of the stricture.

5. The apex of the vaginal flap is advanced to the apex of the incised urethra and is sutured in place with 4-0 PGA sutures (see Fig. 12-4, D). The edges of the vaginal flap are approximated to the urethral mucosal edges using interrupted 4-0 PGA or poliglecaprone 25 sutures (see Fig. 12-4, E).

6. A 14F to 16F Foley catheter is left indwelling for several days.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree