Fecal incontinence affects up to 20% of community-dwelling adults and more than 50% of nursing home residents, and is one of the major risk factors for elderly persons in the nursing home. Institutionalization itself is a risk factor (eg, immobility due to physical restraints). Management should focus on identifying and treating underlying causes, such as diet- or medication induced diarrhea, constipation, and fecal impaction. Use of absorbent pads and special undergarments is useful. Anorectal physiologic testing of nursing home residents has revealed an association between constipation, stool retention, and fecal incontinence. Impaired sphincter function (risk factor for fecal incontinence), decreased rectal sensation, and sphincter dyssynergia (risk factor for constipation and impaction) are found in a high proportion of incontinent nursing home residents. Biofeedback and sacral nerve stimulation may be useful in refractory patients and should be considered before colostomy in community-dwelling adults. Despite appropriate management, nursing home residents may remain incontinent because of dementia and health or restraint related immobility.

Fecal incontinence is a silent epidemic among affected ambulatory patients; only about one-third of the affected individuals inform their care providers of the problem. Factors associated with fecal incontinence include traumatic injury, neurologic deficits and inflammatory conditions of the anorectum, and defecatory disturbances associated with constipation and diarrhea. Fecal incontinence is encountered in more than 50% of nursing home residents, and is associated with significant morbidity and use of health care resources. A recent study of residents in skilled nursing facilities in Wisconsin confirmed that dementia and advancing age were consistently associated with the development of fecal incontinence, but the strongest associations were impairment of activities of daily living and the use of patient restraints. In this review the authors discuss the problem of fecal incontinence in the community-dwelling elderly population and in nursing home residents.

Fecal incontinence in community-dwelling elderly individuals

Fecal incontinence affects up to 20% of ambulatory community-dwelling elderly subjects. Targeted treatment is based on addressing underlying pathophysiologic mechanism(s) as well as management focused on social or hygienic issues.

Pathophysiology

Fecal incontinence is a consequence of many factors, and may result from deficits in internal or external anal sphincter or pelvic floor muscle function. The loss of endovascular cushions due to disruption of the hemorrhoidal plexus, impaired anorectal sensation associated with chronic constipation, poor rectal compliance and compromised accommodation from aging, inflammatory bowel disease, radiation enteritis or pelvic surgery, or neuropathy affecting the pudendal, sacral, spinal, or central nervous system may contribute to fecal incontinence. In some patients incomplete evacuation of stool, large stool volume, liquid stool, and the irritant effect of bile salts in the rectum may also contribute to fecal incontinence.

Management of Ambulatory Patients with Fecal Incontinence

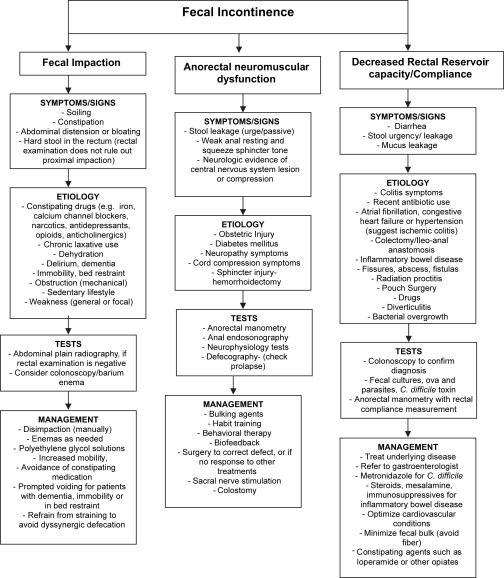

An appraisal of a patient’s history including potential predisposing factors, detailed drug history, particularly constipating drugs or excessive laxatives, and a systematic physical, neurologic, and rectal examination should provide vital clues that will facilitate management ( Fig. 1 ). Therapy with a multilevel approach is outlined here.

Impacted stool requires manual disimpaction. If the stool is hard and difficult to expel, placing the patient on a regimen of controlled evacuation with suppositories or enemas at regular intervals may be necessary. Specific treatment of the underlying problem of diarrhea or constipation with increased fiber is important. Loperamide (Imodium) or diphenoxylate (Lomotil) dosed correctly will slow transit and solidify the stool.

Biofeedback has improved fecal incontinence in 50% to 67% of selected patients in controlled and uncontrolled reports and in short- and long-term studies. This behavioral approach consists of improving external anal sphincter muscle strength, rectal sensation, and rectoanal coordination. A recent randomized, controlled trial of biofeedback as first-line treatment showed little advantage over conservative medical treatment, but one long-term study showed significant improvement in patients who failed conservative treatment.

Patients with fecal seepage have impaired rectal sensation and inappropriate elevation of anal sphincter pressure during defecation, particularly associated with “excessive” straining-induced inadvertent closure of the external anal sphincter. Biofeedback to improve rectal sensation and timing of anal sphincter relaxation can ameliorate this symptom. A less labor-intensive approach of advising the patient to refrain from straining during defecation to avoid the development of obstruction to the outflow of the stool is logical, but has not been evaluated. Studies designed to establish efficacy and develop predictors of compliance with such a simple recommendation deserve to be assessed.

Fecal incontinence associated with rectal prolapse, rectovaginal fistula, or neurologic problems such as spinal cord injury may be amenable to surgery. The integrity of the anal sphincter and the intactness of rectal sensation can be determined by anorectal manometry. Anal ultrasound provides precise assessment of the integrity of external and internal anal sphincter muscles. Such objective anatomic data can facilitate more accurate reconstruction. Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency measures the neuromuscular integrity of the terminal portion of the pudendal nerve and the anal sphincter muscle. This test separates neuropathy (prolonged latency) from rectal wall disorders and provides an explanation for muscle weakness. Reconstructive surgery may not be successful in patients with pudendal neuropathy. Other surgical procedures include anterior repair, artificial bowel sphincter, and sacral nerve stimulation. Except for colostomy, none of these interventions (eg, external sphincter sphincteroplasty, pelvic floor muscle plication, neosphincter) can guarantee total continence. It is important that the patient is made aware of this limitation to minimize disappointment.

Several reports were published in the past year describing efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation for treatment of fecal incontinence refractory to medical management. One randomized, controlled study reported that sacral nerve stimulation was more effective than optimal medical therapy for severe fecal incontinence. Patients (aged 39–86 years) with severe fecal incontinence were randomized to have sacral nerve stimulation (study group; n = 60) or best supportive therapy (control; n = 60), which consisted of pelvic floor exercises, bulking agent, and dietary manipulation. Full assessment included endoanal ultrasound, anorectal physiology, 2-week bowel diary, and fecal incontinence quality of life index. The follow-up duration was 12 months. The sacral nerve stimulation group was similar to the control group with regard to gender (F:M = 11:1 vs 14:1) and age (mean, 63.9 vs 63 years). The incidence of a defect of ≤120° of the external anal sphincter and pudendal neuropathy was similar between the groups. Trial screening improved incontinent episodes by more than 50% in 54 patients (90%). Full-stage sacral nerve stimulation was performed in 53 of these 54 “successful” patients. There were no septic complications. With sacral nerve stimulation, mean incontinent episodes per week decreased from 9.5 to 3.1 ( P <.0001) and mean incontinent days per week from 3.3 to 1 ( P <.0001). Perfect continence was accomplished in 25 patients (47.2%). In the sacral nerve stimulation group, there was a significant ( P <.0001) improvement in fecal incontinence quality of life index in all 4 domains. By contrast, there was no significant improvement in fecal continence and the fecal incontinence quality of life scores in the control group. The investigators concluded that sacral neuromodulation significantly improved the outcome in patients with severe fecal incontinence compared with the control group undergoing optimal medical therapy. In one observational study, 4 (29%) of 14 patients (mean age 54 years, range 30–72) with disabling fecal incontinence resulting from obstetric injury did not have a significant benefit from temporary sacral nerve stimulation and 2 of these patients subsequently had a colostomy. The investigators concluded that sacral nerve stimulation offers improvement in continence and quality of life in patients with fecal incontinence whose other option might be a permanent colostomy.

Management of the Social and Hygienic Aspects of Fecal Incontinence

Loss of self-esteem and self-confidence, disruption of relationships, and impairment of social and occupational activities are common in patients with fecal incontinence. Prompt changing of soiled pads or clothes, storage of soiled material in airtight containers, and appropriate hygienic measures can mask the odor associated with fecal incontinence. Perineal washes can disguise the smell of feces. Foods that can cause malodorous discharge vary from patient to patient, and limiting their consumption is prudent. For bedridden or unconscious patients with severe diarrhea, a fecal collection pouch, rectal tube, or anal plug device may be useful. Moist tissue paper (eg, baby wipes) that is not abrasive is preferable to dry toilet paper for cleansing of the perianal skin. Barrier creams (eg, menthol/zinc oxide ointment [Calmoseptine]) may prevent skin excoriations. Perianal fungal infection should be treated with topical antifungal agents (eg, clotrimazole [Mycelex]). When skin breakdown occurs, diversion of the fecal stream or changing the bedridden patient’s position frequently is indicated. Scheduled toileting or prompted voiding with a commode at the bedside or a bedpan, and supportive measures to improve the general well-being and nutrition of the patient, may all play an effective supportive role.

If incontinence is left untreated a host of dermatologic complications can occur, including incontinence dermatitis, dermatologic infections, intertrigo, vulvar folliculitis, and pruritus ani. The presence of chronic incontinence can produce a vicious cycle of skin damage and inflammation because of the loss of cutaneous integrity. Minimizing skin damage caused by incontinence is dependent on successful control of excess hydration, maintenance of proper pH, minimization of interaction between urine and feces, and prevention of secondary infection. An anorectal dressing offers an effective, comfortable alternative to a pad for absorbing leaked feces that seems acceptable to men.

Fecal incontinence in nursing home residents

Fecal incontinence may be a marker of increased mortality and declining health in nursing home residents. In one study, 20% of nursing home residents developed new onset of fecal incontinence during a 10-month period after admission. Long-lasting incontinence was associated with reduced survival.

Pathophysiology

Important risk factors associated with fecal incontinence in nursing home residents include immobility and dementia, which preclude residents from getting to the toilet in a timely fashion. Paradoxically the use of patient restraints was the most significant cause for the development of incontinence in nursing homes in one recent report, when the data were adjusted for the major reasons (dementia, blindness, arthritis, and stroke) to apply patient restraint and other risk factors for incontinence. The development of fecal incontinence is one of the major risk factors for elderly persons who have been placed in the nursing home. Impaction in the rectum with liquid stool leaking around the fecal mass is often associated with fecal incontinence in an elderly institutionalized person. When toileting assistance is not immediate, failure to perceive the arrival of stool in the rectum may produce severe urgency to defecate or leakage of stool.

Two studies that did not involve a toileting program have confirmed that dementia and immobility play a key role in the development of fecal incontinence. A retrospective study found that 46% of 388 nursing home residents were affected by fecal incontinence. Although diarrhea was the strongest risk factor, dementia actually played a greater role in the development of fecal incontinence. Borrie and Davidson also found that 46% of subjects (among 457 long-term care hospital patients) had fecal incontinence, and concluded that immobility and impaired mental function were independent predictors of fecal incontinence. Immobility was the strongest predictor of fecal incontinence as measured by nursing time spent toward assisting incontinent patients, and handling laundry and incontinence supplies.

The role of these risk factors can be minimized by a prompted voiding program, even if residents have disorders that contribute to their fecal incontinence. Two studies have estimated the effectiveness of scheduled toileting programs in reducing the frequency of fecal incontinence. The results provided insight into the extent to which immobility and dementia contribute to this condition. In one study, toileting assistance for urinary incontinence offered to male and female residents every 2 hours significantly decreased urinary incontinence and significantly increased the number of appropriate bowel movements from 23% to 60% (n=165). Although the frequency of fecal incontinence was not decreased significantly, there was a trend in this direction. The second urinary incontinence treatment trial involved a comprehensive intervention that integrated toileting assistance (prompted voiding), a fluid-prompting protocol, and exercises to improve mobility. Residents showed significantly decreased urinary incontinence, increased fluid intake, and improvement in mobility endurance. This program also resulted in a significant decrease in the frequency of fecal incontinence from 0.6 to 0.3 episodes per day and a significant increase in appropriate fecal voiding in the toilet. However, the frequency of fecal incontinence was only measured over 2 days and 46% of the residents had no fecal voids (continent or incontinent), revealing that constipation remained a persistent problem. The lack of a significant difference between the intervention and control groups in the total frequency of fecal voids during this 2-day monitoring period suggested that constipation was not alleviated by the intervention. Neither of these trials controlled for laxative use, medications with constipating side effects, or caloric intake that was known to be very low with consequent fiber intake that may have also been low. Also, anorectal function was not determined.

Several gastrointestinal disorders can play a role in the etiology of fecal incontinence in nursing home residents. Common causes are impaired anorectal sensation, lower sphincter squeeze pressures, and reduced integrity of sphincter or pelvic floor muscles. One report described a subset of mentally intact but immobile nursing home residents—particularly stroke victims—who have fecal incontinence but have normal anorectal function. These residents require assisted toileting more than any other interventions. This small study compared anorectal measurements for four nursing home residents who had fecal incontinence, six ambulatory, elderly community-dwelling subjects who had fecal incontinence, and four controls without fecal incontinence. Two of the four nursing home residents had normal measurements on anorectal testing, with normal squeeze duration and squeeze pressures. Despite having intact mental status and an awareness of impending bowel movement, both individuals had stroke-related impairment of their mobility and therefore required toileting assistance. However, the other two nursing home subjects had reduced squeeze pressures and other abnormalities compared with controls. The results suggest that although symptoms normally correlate with manometric abnormalities in ambulatory persons with fecal incontinence, such a correlation may not exist among immobile nursing home residents with fecal incontinence. An incorrect diagnosis of the factors influencing fecal incontinence may have a negative effect on the perception of nursing home residents regarding their management, and may partially account for the disparity between their observed symptoms and anorectal measurements.

Constipation plays an integral role in the development of fecal impaction and fecal incontinence among the institutionalized elderly. The incidence of constipation increases with age and is also attributable to immobility, “weak straining ability,” the use of constipating drugs, and neurologic disorders. Defined as two or fewer bowel movements per week, hard stools, straining at defecation, or incomplete evacuation, constipation can result from a combination of lack of dietary fiber intake, poor fluid intake and dehydration, and the concurrent use of various “constipating” medications. Fecal impaction, a leading cause of fecal incontinence in the institutionalized elderly, results largely from the person’s inability to sense and respond to the presence of stool in the rectum. Decreased mobility and lowered sensory perception are common causes. A retrospective screening of 245 permanently hospitalized geriatric patients revealed that fecal impaction (55%) and laxatives (20%) were the most common causes of diarrhea, and that immobility and fecal incontinence were strongly associated with fecal impaction and diarrhea.

Constipation, fecal impaction, and overflow fecal incontinence are common events in nursing home residents. Until recently, in the absence of comprehensive anorectal testing, drug-induced constipation was considered the likely explanation. The high prevalence of constipation in nursing home residents, however, is only partly due to adverse drug effects. Systematic anorectal testing of nursing home residents with fecal incontinence was reported in a recent study. This report documented impaired sphincter function (risk factor for fecal incontinence), decreased rectal sensation, and sphincter dyssynergia (risk factor for constipation and impaction) affecting up to 75% of the assessed residents. The sphincter dyssynergia documented in these nursing home residents with fecal incontinence sheds new light on the association between constipation and fecal incontinence in nursing home residents.

Treatment Options for Fecal Incontinence in Nursing Home Residents

When fecal incontinence is associated with diarrhea, it is important to treat underlying disorders. Conditions such as lactose malabsorption (or intolerance), bile salt malabsorption, and inflammatory bowel disease are treatable. Antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide and diphenoxylate, or bile acid binders such as cholestyramine may help. A gradual increase in the intake of dietary fiber can relieve constipation for many elderly patients. In a study of institutionalized elderly patients, the use of a single osmotic agent with a rectal stimulant and weekly enemas to achieve complete rectal emptying reduced the frequency of fecal incontinence by 35% and the incidence of soiling by 42%. If fecal impaction is not relieved by laxatives and toileting, digital manual disimpaction may be necessary, followed by tap water enemas two or three times each week, and possible use of rectal suppositories. The practice of routinely prescribing stool softeners, saline laxatives, stimulant laxatives, and single-agent osmotic products as prophylactic treatment against constipation and impaction deserves to be reexamined. In the presence of impaired sphincter function and decreased rectal sensation, the fluidity of the stool induced by the use of laxatives and stool softeners administered to prevent constipation and impaction may in fact predispose the nursing home residents to manifest fecal incontinence. The recent finding of anal sphincter dyssynergia in a high proportion of nursing home residents with fecal incontinence suggests that a new approach to the management of fecal incontinence should consist of neuromuscular conditioning to improve the dyssynergic sphincter function. Even though the efficacy of biofeedback therapy has been demonstrated by a randomized, controlled trial in ambulatory patients, in nursing home residents dementia and immobility may limit the effectiveness of such treatment. Hence, other novel approaches deserve to be considered. The approach using increased fibers and prompted voiding is a reasonable combination worth testing. Instructing the patients to refrain from straining to avoid dyssynergic defecation also seems logical. Nursing homes lack the staff and financial resources to provide residents with sufficiently frequent toileting assistance (including prompted voiding). These deficiencies need remedies.

Skin Care in Nursing Home Residents with Incontinence

The use of a skin care program that includes a cleanser and a moisture barrier is associated with a low rate of incontinence-associated dermatitis. The use of a polymer skin barrier film three times weekly is effective in preventing incontinence-associated skin breakdown. One uncontrolled trial described the use of an innovative adult brief that encouraged skin cleansing during incontinence care. The system was easily and effectively incorporated into the nursing home, and favored by certified nurse assistants whenever available (97% of the time). Patterns of incontinence care differed at follow-up, with the one-step incontinence system being compared with wipes placed at the bedside. This novel approach results in less linen used, fewer wipes used, and fewer interruptions of the certified nurse assistant during care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree