Fig. 13.1

Bristol stool scale (From Lewis and Heaton [52]. Reproduced with permission of Informa Healthcare © 1997)

Defining exactly when the problem with fecal control occurs is another important clue. For instance, do they feel like they fully empty their rectum (as may be seen when stool is trapped in a rectocele and may leak out after they leave the bathroom)? Do they have soilage or leakage in the first several hours after defecation (again stool trapped in a rectocele or stool retained in the rectum after evacuation)? Do they have loss of stool while sleeping (very unusual)?

Obstetrical history is also crucial, including number/weight of children, unusual presentation at delivery, prolonged labor, episiotomy, or tears of the perineum. Basic language helps to delineate some of these issues, such as asking if the doctor needed to use sutures in the vaginal area. Also most women remember if they had changes in bowel or bladder control after a delivery and if this had fully resolved.

Dietary choices can greatly affect stool quality, and a review of what, how much, when, and changes may elucidate a culprit that can be modified.

Many systemic diseases affect defecation and stool evacuation, especially diabetes, scleroderma, and multiple sclerosis. Also other central nervous system problems, which include back surgery or back injury, may lead to alterations in nerve signals to the intestine and the pelvis and should be investigated. Medications, including some herbal/health food store brands, change stool character, and ascertaining exactly when they were started and the relationship to any perceived changes in stool consistency should be sought. Many patients do not link the two, so careful questioning can assist in this endeavor.

Anal, pelvic, or abdominal surgery may also influence defecation, along with any anal trauma or injury. This would include anal intercourse or sexual abuse—both areas that surgeons typically are uncomfortable to investigate, though are crucial to ask about. Additionally, prior radiation treatment to the pelvis or a congenital malformation in the pelvis should be noted.

A large percentage of women may be experiencing other pelvic floor problems such as urinary incontinence, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, or vaginal prolapse. While these may not directly affect fecal control, your treatment options may be influenced by other pelvic disorders.

As a general rule, questions about alcohol, tobacco, illegal drug use, family history of bowel problems, and general health care (including colonoscopy) are important as they may provide clues that tailor which treatment options would be optimal for an individual patient.

Although not often as publicized, men experience problems with fecal control as well. Life-changing events such as loss of a spouse or divorce (i.e., diet may then have changed after spouse no longer cooks for them) or change in job (additional stress leads to a change in stool character) are particularly important to note along with all other points outlined above that would pertain to men. One study that specifically examined 43 males with fecal incontinence found that 77 % were classified as having fecal leakage and 23 % fecal incontinence [4]. Forty percent of those with leakage had a sphincter defect compared with 70 % in the fecal incontinent group. All patients with leakage improved with lifestyle changes and biofeedback, while 6/10 in the fecal incontinent groups required surgical intervention such as sacral nerve stimulation or other involved treatments. The authors concluded that males with fecal incontinence (versus leakage) had some type of sphincter weakening that typically requires surgical treatment. Table 13.1 summarizes the key elements that need to be discussed during the history.

Table 13.1

Key concepts to be covered when obtaining the history

Clarify what the patient perceives as lack of fecal control |

Clarify what and when the fecal incontinence occurs |

How often does this occur |

Associated fecal urgency |

Affect on daily activities |

Character of stool |

Changes in pattern of defecation over decades of life |

Changes in defecation with menstruation |

Obstetrical history |

Dietary history and relation to bowel issues |

Other systemic diseases (i.e., diabetes, scleroderma, multiple sclerosis) |

History of back injury or back surgery |

Medications including herbal and over the counter and the temporal relationship to medication changes and the start of fecal incontinence |

Anal surgery or trauma including anal intercourse |

History of sexual abuse |

Abdominal or pelvic surgery |

History of radiation treatment to the pelvis |

Congenital malformations (especially in the pelvis) |

Other pelvic floor problems (i.e., urinary incontinence, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, vaginal prolapse) |

Life-changing events (i.e., death of spouse or life partner, change in job) |

Physical Examination

Key Concept: A thorough examination involves evaluation of everything from the undergarments and perineal skin to the perineum, including both rectal and vaginal examinations, and abdomen. Validated scoring systems will assist in quantifying and tracking progress.

The physical examination focuses generally on the abdomen and perineum. The abdominal exam generally keys on scars, masses, distension, and tenderness. When looking at the perineum, I first note the underclothes and perianal skin for any signs of soilage, along with any skin irritation (Fig. 13.2) or anal scars over the perineal body or over the anal skin. I typically examine patients in the left lateral position. In women I look in the vagina and note, with strain, any descent of the vaginal wall. I may also digitize the vagina again to clarify vaginal descent or simultaneously digitate the anus and vagina to again clarify descent. I ask them to strain and also note anal descent. When I see that the anal area move 4–5 cm and take on the shape of a bowel, this may be associated with damaged support structures, straining, and defecation problems. While there are patients that have descent and no defecation issues, it is something to keep in mind in combination with the history as clues to the etiology of the fecal incontinence. These patients may not be totally emptying their rectum or have an element of internal prolapse that may be adding to their symptoms. The anal and perianal skin requires close inspection first looking at the length of the perineal body. I ask them to squeeze and look for anal muscle movement. Many times there is excessive buttock movement as patients have gotten into the habit of squeezing all muscles in that region in an effort to avoid the horrifying aftermath of fecal leakage. To determine if they can contract their anal muscle, touching the skin over the anal muscle and asking them to pull only that muscle toward their umbilical area will clarify for them the muscle to contract and allow you to detect anal sphincter movement. On digital anal exam, differentiating between movement of the levator muscle and anal sphincter when squeezing should be noted, as you may be falsely believe the patient has sphincter tone when in fact is coming from higher in the canal. Again asking them to pull the muscle to their umbilical area may assist in detecting anal sphincter movement. Also important is anal muscle fatigue, which may be detected after several prolonged (about 15 s) anal sphincter contractions. For patients with significant fatigue, anal muscle retraining and strengthening is strongly considered as part of the treatment plan. On digital anal exam, a mass, the stool content (and character), presence of a rectocele, and abdominal contents that impinge on the rectum with strain should also be considered. An anoproctoscopy is helpful if there is suspicion of a mass or proctitis.

Fig. 13.2

This patient has severe anal excoriation from leakage of mucus and liquid stool at her anal verge. The other marks across her skin and buttocks are classic from continuous sitting on a heating pad in an unsuccessful attempt to alleviate the discomfort (Reproduced with permission from Tracy Hull, MD The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Cleveland, Ohio)

Quantitative tools of evaluation such as incontinence scores and quality of life scales may be employed. They are helpful when looking for improvement or change after a treatment intervention. However, they should never replace a comprehensive history. Some form of incontinence tool is mandatory to determine using sacral nerve stimulation, which will be discussed in more detail below. As there are many acceptable tools used for the purpose of fecal incontinence, choosing one that works for you and your office staff and administering the questionnaires before seeing the patient and after treatment interventions will allow familiarity with its nuances and use. One study looked at the current popular tools to score fecal incontinence (Rothenberger, Wexner, Vaizey, and Fecal Incontinence Severity Index) and found the Wexner scale correlated most closely with subjective perception of severity of symptoms by patients [5]. Another study looked at “responsiveness and interpretability” of the Vaizey score, Wexner score, and Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life scale [6]. These researchers felt none of these popular tools attain the high levels of psychometric soundness needed to be recommended as the best tool to use. They also echo the notion previously stated, that what a patient views as important may be different from the physician. While the Wexner score was felt to be the most suitable for severity assessment, they recommended that several tools should be used for evaluation in an attempt to circumvent these issues. An overview of each tool and its pros and cons are beyond the scope of this paper, but an excellent overview was written by Wang and Varma [7], which outlines some of the commonly used tools.

Testing

Key Concept: Testing is meant to augment or clarify findings on history and physical examination. Ultrasonography is my preferential test to help guide therapy.

Testing is individualized based on the history and physical exam. In appropriate patients, a colonoscopy would be ordered. In some patients where I question their ability to control stool, a fiber enema is administered (Fig. 13.3). This consists of fiber (i.e., a packet or large tablespoon of MetamucilR, Citrucel) that is poured into an empty container and mixed with about 50 cc of water and quickly instilled in the rectum before it has time to gel. Then the patient walks around, bends over, and generally has sustained non-strenuous activity for 5 min to determine if they have leakage of this mixture from their anus.

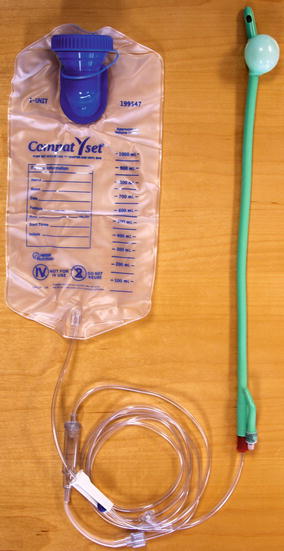

Fig. 13.3

Fiber enema: a packet of fiber or a large tablespoon is placed in an empty enema dispensing container. An empty Fleet EnemaR container works well. Then about 50 cc of tap water is added, and the mixture is quickly shook and then inserted into the rectum. The goal is to insert the mixture before the fiber has a chance to gel making insertion impossible (Reproduced with permission from Tracy Hull, MD The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Cleveland, Ohio)

The utility of anorectal physiology testing was questioned by our center and found not to correlate with incontinence scores [8]. Also ultrasound findings did not correlate with manometry results. We felt that preoperative anal manometry and endoanal ultrasound should be used to guide treatment, but improvement after an overlapping sphincter repair should not be assessed by changes in manometry pressures. This somewhat contradicts data from another unit; however, their aim was somewhat different. They looked at whether anal manometry could separate those patients with fecal incontinence from healthy individuals [9]. They found that patients with fecal incontinence had lower rest and squeeze pressures and lower urge sensation along with a higher volume of first sensation pressures. Overall they found that single studies were not helpful, but the entire panel of anal physiology studies had excellent sensitivity, moderate specificity, and convincing accuracy.

My feeling is that overall anal physiology testing may guide therapy, but I am not sure it is always needed. We rarely order needle EMG looking for neurological damage as it has not proved useful in guiding treatment. Perhaps looking for a sacral reflex before considering sacral nerve stimulation may be a consideration. I am also not sure that pudendal nerve terminal motor latency offers much assistance. Previously we used nerve prolongation, particularly bilaterally, to counsel patients that results after sphincter repair most likely would be poor. However, I have seen patients without prolongation of their pudendal nerves when tested, where absolutely no anal muscle moves when I ask them to squeeze on physical exam. Anal endosonography on the other hand provides a useful road map when considering treatment, and I usually rely on this test (making sure I perform it myself or know that the endosonographer is experienced in accurately depicting sphincter defects). Our unit still typically orders anorectal physiology on most patients because we maintain extensive databases that we may use in future studies; however, we only use the data to selectively counsel patients. For instance, a patient with a low maximal tolerated volume and low anal pressures may not achieve the expected short-term benefit from an overlapping sphincter repair. We would use this information to preoperatively discuss expected outcomes with the patient and aid in navigating the treatment plan. While pelvic magnetic resonance imaging is a consideration instead of or with anal endosonography, I am not convinced it adds enough information to justify the expense. I do not routinely order a defecating proctogram unless there is an accompanying problem with stool expulsion during defecation. Dudding and Vaizey wrote an excellent overview of testing for fecal incontinence and other pelvic floor disorders, and the reader is directed to this review for more in-depth descriptions of the various tests [10].

Treatment Options

Key Concept: From the very beginning, set realistic expectations with your patient and ensure they understand this may involve several different treatment modalities.

The next step in management involves an individual treatment plan for the patient. This does not encompass only one intervention, but could involve several combined modalities customized for the patient and revolves around a clear understanding of the pathophysiology and underlying conditions. Fecal incontinence should be viewed as a chronic disease like diabetes or hypertension. Similarly, in these chronic diseases, several treatment modalities may be needed for optimal control of the disease process and optimization of the patient’s quality of life. Similarly management of fecal incontinence is a long-term notion, and adjustment in the treatment plan will be necessary as needed. This also involves setting realistic expectations for the patient and the surgeon (i.e., some health-care provider must be prepared to assist and manage this patient long term). Society typically views defecation issues as voluntary (i.e., mind over matter) which adds to unrealistic goals determined by the patient. Therefore, attaining “perfect” bowel function may not be a realistic goal, and the health-care provider should emphasize improvement and improvement in quality of life as the goals.

Conservative Management

Key Concept: Almost every patient will require medical management, which typically involves dietary supplements and one (or more) of several classes of medications.

Most treatment plans include some element of conservative management. Any issues with loose or soft stool can contribute to problems with control. Evaluation and treatment alone of diarrhea (or just loose stool) can sometimes greatly improve the patient’s situation. These include fiber supplementation (taken with the least amount of water) pectin, and medication. Loperamide is a typical medication used, and instructions for use must be carefully discussed as the instructions on the package may not be appropriate for each patient’s problem. Depending on the pattern of defecation, perhaps starting with one pill/capsule (2 mg) each morning could be the initial recommendation for this medication. The goal is titration to avoid fecal incontinence but not too much that produces constipation; however, this may not be possible. If one pill is too much, the liquid form administered to children can be used so the dose can be decreased. Also if constipation is an issue, using the medication every other day or every 3 days per week may allow therapeutic benefit for the incontinence without precipitating constipation.

Skin irritation frequently accompanies fecal incontinence or may even be the true reason a patient seeks medical assistance. Counseling regarding skin care therefore is also part of conservative treatment. Barrier creams that typically employ zinc (such as CalmoseptineR, Calmoseptine, Inc., Huntington Beach, California) and lanolin (make sure they are not allergic to wool) may be lathered onto the anal skin like frosting (i.e., a thick layer). Patients should place these creams up to the dentate line for complete protection. They may stain underclothes, so patients should be warned of this possibility. Antibiotic ointments are rarely required, and occasionally an antifungal powder may need to be dusted on the skin if Candida is detected. This can be applied using a cotton ball (dusted over the barrier cream) and then leaving the cotton ball by the anus to wick away moisture (similar to cotton socks used in athletic activity). Since anal irritation may lead some patients to feel that their anal area is unclean, they may wipe that region excessively (similar to polishing furniture but instead polishing their anus). Advising them to wipe with unscented baby wipes or wet paper towel and avoid using soap and a washcloth in the shower along with minimal wiping after defecation can aid in improving anal irritation from excessive wiping.

Dietary manipulation may be advised if certain foods lead to loose, urgent, or uncontrolled stools. A food diary that corresponds to incontinent episodes may clarify offending foods. Fresh fruit and vegetables can make stools loose and add to urgency. Many patients have concerns with excessive or uncontrollable flatus. A low carbohydrate diet may reduce flatus. While many anti-gas (over-the-counter) medications can be recommended, many patients find these unhelpful with flatal incontinence. For severe problems with excessive flatus, an intermittent short course of antibiotics (rifaximin [XifaxanR] is a popular choice) can be prescribed, but many effective agents are very expensive. Metronidazole is another choice that is less expensive, but side effects such as an Antabuse effect, tin taste in the mouth, or peripheral neuropathy must be considered before prescribing. These agents will change the flora and decrease intestinal gas temporarily. Therefore, the medication must be repeated with the goal of the least days per month possible to attain relief. One way I advise taking antibiotics for this purpose is 1 week out of every month, which in my experience seems to adequately reduce issues with excessive flatus. Probiotics also are helpful for some patients with excessive gas issues.

Since a lot of information may be recommended regarding conservative therapy, it is extremely helpful to give precise written instructions for skin care and bowel-altering medication so the patient has exact instructions to follow and does not need to rely on memory to implement suggested changes or treatment. Since it is important to individualize the treatment, we do not use standardized forms and actually type out the instructions that are also filed in their chart.

For some patients with leakage, especially when it seems to occur directly after they leave the bathroom, a tap water or rinsing enema after defecation will eliminate any retained material and alleviate the problem. While many patients do not prefer this approach, if explained in a positive light and the patient successfully uses this treatment, they may change their mind. I typically recommend that an empty phosphate soda enema container be used (they can use the actual phosphate enema for irrigation rather than discarding it, then the container can be filled with water and used five to eight times again before the material cracks). Alternatively, a large catheter can be used to instill 50–200 cc of tepid tap water. I emphasize it is like “rinsing” out the rectum.

For some, a large volume water enema may be needed if they are using this treatment for more than minor leakage. For those patients, my nurse will discuss using a large volume enema consisting of 500–1,000 cc or water. This is delivered via a 28-Fr Foley catheter (as this has a 30-cc balloon that can be inflated if necessary) (Fig. 13.4). The fluid is placed in a tube feeding administration bag as this has a valve to regulate the inflow of fluid rather than straight tubing which otherwise allows the liquid to run in quickly. The catheter must be well lubricated and this is emphasized. We ask them to start with 500 cc and increase the amount weekly over 4–6 weeks. They are also counseled to allow 45–60 min to perform the irrigation and evacuation daily. It also tends to be more successful if performed at the same time daily (typically in the early morning). Encouragement and patience is provided by my nurse, and this seems to enhance success with this treatment. An extension of this thought process is the antegrade continence enema. A surgical procedure is performed where the appendix or a tapered segment of terminal ileum is brought to the surface to form a flush stoma about the size of a 10-French catheter. Water is instilled via the small stoma, which then flushes out the entire colon via the antegrade approach. While this therapy tends to be more popular in the pediatric population, selected adults are quite satisfied doing irrigation by this method.

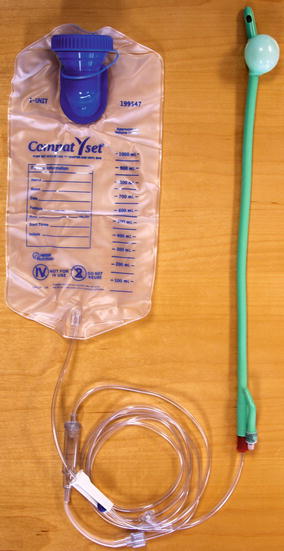

Fig. 13.4

For a large volume enema, a 28-Fr Foley is lubricated and inserted into the anus. For patients who cannot retain fluid, the balloon can be inflated with up to 30 cc and pulled back to rest against the pelvic floor. Then 500–1,000 cc of water is placed in the bag. Tubing connects the bag to the Foley. There is a control valve on the tubing. Fluid can be instilled under direct control of the patient via the control valve into the rectum and left colon (Reproduced with permission from Tracy Hull, MD The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Cleveland, Ohio)

Other Therapies

Key Concept: Progressively invasive treatment options are available. Each has its own strength and weaknesses, depending on the severity of incontinence and underlying pathology.

Physical Retraining (Biofeedback)

Physical retraining of the pelvic floor is also a treatment that may improve the patient’s situation (and does not worsen) and should be considered. It is important to be alert to the fact that some insurance companies will not reimburse for this treatment. Also a therapist (whether a physical therapist, nurse, or other interested health-care provider) may not have specialized specific training for pelvic floor issues and may not provide the most optimal teaching. The Cochrane review done by Norton and Cody identified 21 studies with a total of 1,525 patients [11]. They found severe methodological weaknesses in nearly all studies reviewed but concluded that perhaps some portions of biofeedback and sphincter exercises may have therapeutic effect. The authors emphasized that this was not definitely shown in their review and larger well-designed trials were needed.

Anal Plug

For minor leakage, the anal plug may be considered. The recent Cochrane review looked at four studies of 136 patients [12]. They noted that the rate of intolerance or ineffectiveness from reviewed studies was 35 %. In the short-term (not considering any long-term results), anal plugs, when tolerated, could provide continence. They also noted that overall satisfaction was better when polyurethane plugs were used versus polyvinyl-alcohol plugs. Experience worldwide with plugs is limited. This device should be considered in patients with minor leakage, but dislodgement or intolerance is an issue. They can be obtained in various types, designs, and sizes. Insurance coverage may be limited. They also may be considered as part of a larger treatment plan for a patient.

Radiofrequency Energy (RFE)

Radiofrequency treatment of the anal sphincter has been available for over a decade and is administered per the SECCAR machine and protocol (Figs. 13.5 and 13.6). Two recent studies have looked at its effectiveness. One study looked at pre-procedure and 1-year changes in the Wexner score [13]. Mean improvement from 15.6 to 12.9 (p = 0.035) and mean improvement in 3 of 4 Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life subsets were found. There were minimal complications, with 3 limited episodes of post-procedure bleeding. Another study of 27 patients found a sustained long-term response in 22 %, but 52 % of patients required additional treatment interventions at a mean follow-up of 40 months [14]. We have offered this treatment to select patients with mild-to-moderate fecal incontinence and an intact sphincter. How this will fit into our algorithm with the approval of new therapies will need to be determined. We have had minimal complications, and reimbursement, overall, has not been an issue; therefore, it can be considered when few options exist. One note of caution, use of RFE after a patient has been treated with an injectable agent has been discouraged. The theoretical concerns are that the needles would be deployed into the injected implant and have no effect on stimulation and heating of the connective tissue in the anal region. Also the potential for infection of the injected implant has also been raised as a possible complication. I am not aware of any studies definitively reporting this as happening, but this possibility has been raised and should be acknowledged. Therefore, if the use of RFE is being contemplated, its use should be considered before treating with an injectable agent.

Fig. 13.5

The handpiece for the SECCA® procedure shown with the needles deployed. The handpiece is inserted in the anal canal starting at the dentate line and the four needles deployed into the tissue. Radiofrequency is then delivered for 90 s. The needles are retracted and the probe is rotated 90° and the process repeated until all four quadrants are treated. Then the probe is moved 5 mm proximal, and those four quadrants are treated. The process starts at the dentate line, and typically, there are 4 rows of treatment (Reproduced with permission from Tracy Hull, MD The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Cleveland, Ohio)

Fig. 13.6

Shown is the handpiece inserted in the anal canal with the attachments (Reproduced with permission from Tracy Hull, MD The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Cleveland, Ohio)

Injectables

Key Concept: While preliminary results have shown success in small studies, several questions remain regarding the ideal substance, technique, and population. I prefer to use it in mild-to-moderate incontinent patients with a thinning or fibrotic internal sphincter complex.

There are over ten different materials that have been reported as injectables into the anal region for fecal incontinence. The Cochrane review of this subject highlights the diversity of this material, along with the lack of well-designed studies, prohibiting these authors from making definitive conclusions [15]. This was echoed in a review of 13 case series and one randomized controlled trial, in total involving 420 patients, by Luo and Samaranayake [16]. These authors also concluded that future appropriately designed randomized controlled trials with large study populations and longer follow-up are needed to truly evaluate injectables.

The only injectable that has been Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in the United States is dextranomer in stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASA DxR). In the randomized monitored study for FDA approval, 52 % of patients being injected had >50 % reduction in fecal incontinence episodes compared to 31 % of those receiving a sham injection who reported the same degree of improvement [17]. The high degree of improvement in the sham group is curious, but placebo treatments for fecal incontinence for unclear reasons seem to have up to a 30 % improvement rate. These results were sustained at 36 months, and all of the quality of life scores showed significant improvement at 36 months [18]. This is a safe procedure with minor bleeding being the most common complication although 2/278 patients in the FDA-monitored study developed an abscess (one rectal, one prostatic) [17].

Besides the lack of sufficient data to guide treatment, other controversies surrounding injectable agents involve technique. Currently, there are seven different techniques found in the literature to administer the agent. The procedure typically involves one cc of this material injected into the submucosal space in four areas at the top of the anal canal. While many inject in the submucosal space, the intersphincteric space may be better. Yet, there are several additional questions that remain unanswered. Would the use of ultrasound to guide injection be superior to blinded injection? This procedure is typically done in the outpatient setting, but would the results improve if done in the OR? Additionally should the needle go through the anal mucosa or be inserted from the perianal skin to the target location? The size of the needle is typically 21 gauge, which seems necessary as the material is quite viscous and difficult to push through the needle. However, is this size of needle correct, as some of the material can be seen oozing out of the injection site at times after the treatment? The exact optimal patient who will benefit from this treatment is also unclear. Some of the patients in the FDA-monitored trial had severe fecal incontinence [17], but would patients with mild-to-moderate incontinence or leakage be better candidates? Also can injectable material be used to augment a defect in the internal sphincter (such as after a lateral sphincterotomy that has leakage) or a divot in the smooth contour of the anal canal, which is leading to leakage? All these questions surround using this material.

Our practice continues to be performing this procedure in the outpatient setting. We target patients with mild-to-moderate fecal incontinence. Also we would offer this to a patient with internal sphincter thinning or fibrosis as seen on anal endosonography. The patient receives a phosphate enema before and then is typically positioned in the left lateral position. Using a long beveled anoscope, Betadine is swabbed in the anal canal (a plain wet swab is used if the patient reports an iodine sensitivity that is concerning). The nurse steadies the anoscope after it is placed in position. The physician steadies the needle with one hand and injects with the other. The material is injected about 1 cm cephalad to the dentate line. We use digital guidance to inject in the submucosal space in four quadrants and turn the needle a quarter turn before withdrawal in attempt to prevent material leakage. Postoperatively, we do not issue any restrictions in activity and give advice on keeping stools soft. We ask patients to call immediately if they have pain, bleeding, or fever.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree