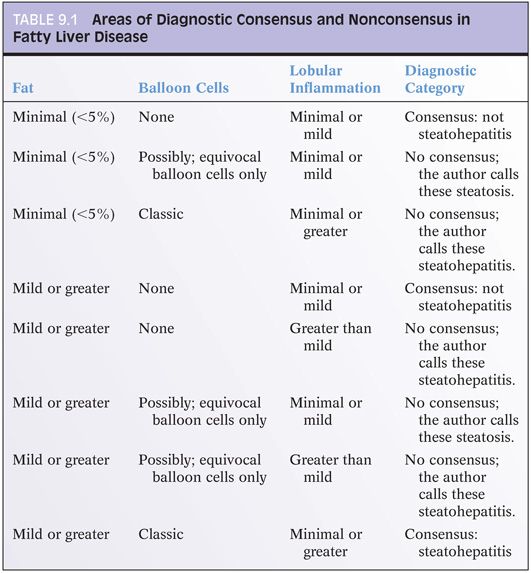

The amount of fat is generally scored as minimal (less than 5%), mild (6% to 33%), moderate (34% to 66%), or marked (more than 67%). The general consensus is that only the macrovesicular component should be scored and that scoring is best done at a low-power lens, such as a 4× or 10×. Some cases can have relatively more abundant intermediate-sized fat droplets and may be more challenging to score. If you go on too high of a lens, it makes this challenge even more difficult. So stay at around a 10× to make the estimate. Another common source of error is to overthink this process. If you try to decide if a case has 33% versus 34% fat (less than or equal to 33% fat separates mild from moderate steatosis in many grading schemas), you are likely to feel a little uncertain about any final fat estimate—instead, use a low-power lens and think in terms of minimal, mild, moderate, and marked. The human eye is much better at identifying large categories than it is at more precise percentages. The percentages that accompany the categories of minimal, mild, moderate, and marked steatosis are for reference in the hopes of uniform categories across the literature.

The fat can be distributed in different patterns within the hepatic lobules. With a zone 3 distribution (Fig. 9.2), the fat clusters around the central veins, whereas with a zone 1 pattern, the fat clusters around the portal tracts (eFig. 9.2). Often, it is easier to look for what zone is spared from fat when making this distinction. For example, a zone 3 pattern of fat will have little or no fat around the portal tracts. With a panacinar distribution, the fat is typically moderate or marked and no strong distribution patterns are evident. With an azonal distribution, the fat is typically mild but no strong distribution patterns are evident (eFig. 9.3). The zonal distribution does not have any diagnostic significance at this point. The zone 1 pattern may be more common in children and teenagers but can also be seen in adults.

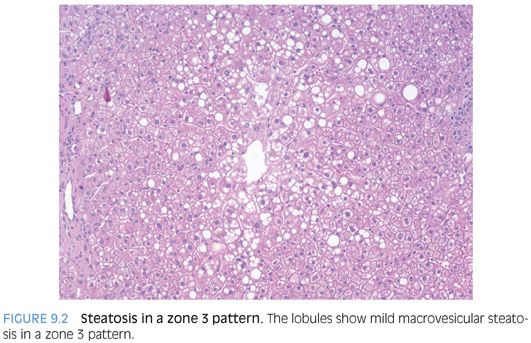

Inflammation

The inflammation in fatty liver disease, both steatosis and steatohepatitis, is generally mild. The portal tracts commonly have mild to focally moderate lymphocytic inflammation composed predominately of mixed B and T cells with rare and inconspicuous plasma cells (Fig. 9.3). In general, biopsies with fibrosis tend to have somewhat more portal chronic inflammation than biopsies without fibrosis. Although the inflammation can be focally moderate, it is generally on the low end of moderate and biopsies with moderate diffuse portal chronic inflammation or marked portal chronic inflammation should raise your suspicion for another disease process. The author has seen several cases of clinically unknown chronic hepatitis C picked up this way—that is, the patient had fatty liver disease histologically, plus more than the expected chronic portal hepatitis, and additional testing revealed previously unknown hepatitis C (eFig. 9.4).

The lobular inflammation varies from minimal to moderate in almost all cases. A biopsy with marked lobular hepatitis would be unusual and should raise your suspicions for a separate disease process. The lobular inflammation is also lymphocytic and composed of T cells. Neutrophils in the lobules are relatively rare in NAFLD, except for when there is markedly active disease with numerous balloon cells and abundant Mallory hyaline (eFig. 9.5). This has been a point of diagnostic confusion for some pathologists over the years, although it seems to be less now than it was before. But to restate, neutrophils are not necessary for the diagnosis of steatohepatitis and in fact are rather rare. As a diagnostic pitfall, beware that wedge biopsies or resections can show significant surgical hepatitis (eFigs. 9.6 and 9.7). When the background liver also shows fatty change, this sometimes can be misinterpreted as steatohepatitis.

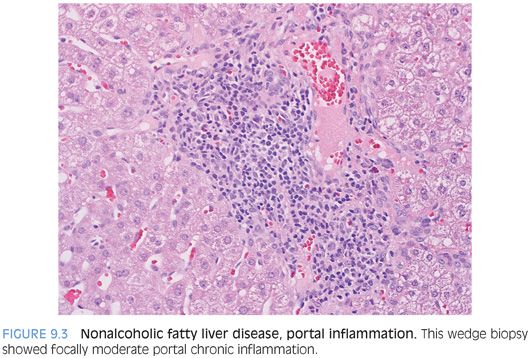

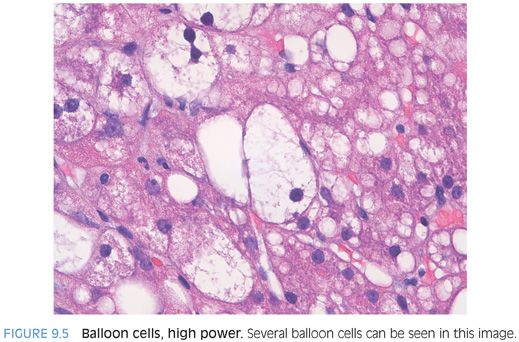

Ballooned Hepatocytes

Balloon cells are hepatocytes that are injured but not yet dead. The precise molecular reason why they balloon is not clear. Balloon cells can also be seen in other diseases, such as cholestatic liver disease. Balloon cells are hepatocytes with large amounts of clear, rarified cytoplasm, often with scattered small eosinophilic clumps and perhaps with Mallory hyaline. They typically lack fat droplets (Fig. 9.4). They should stand out and be evident when scanning on a low-power lens (Fig. 9.5, eFigs. 9.8 and 9.9). If you spend too much time on a high-power lens, lots of hepatocytes that are not balloon cells will soon start to look like balloon cells. In fatty liver disease, the balloon cells can be found anywhere but are most commonly found in zone 3. When there is fibrosis, the balloon cells often are located in close proximity to fibrous bands.

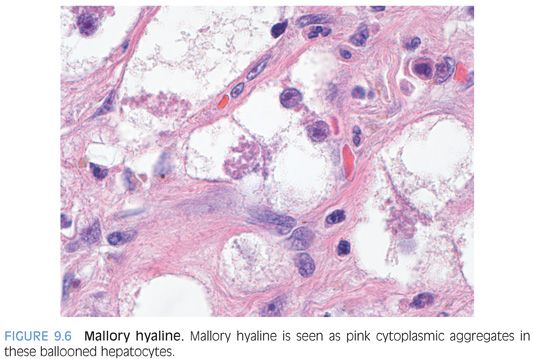

Balloon cells often contain Mallory hyaline, and almost all Mallory hyaline will be seen within balloon cells (Fig. 9.6). Mallory hyaline is seen as eosinophilic material in the hepatocyte cytoplasm that can be either clumped or ropy. Mallory hyaline is composed of damaged and ubiquitinated cytoskeleton proteins. Although immunostains are not necessary, you can stain the hyaline with ubiquitin, p62, or cytokeratins 8 and 18.

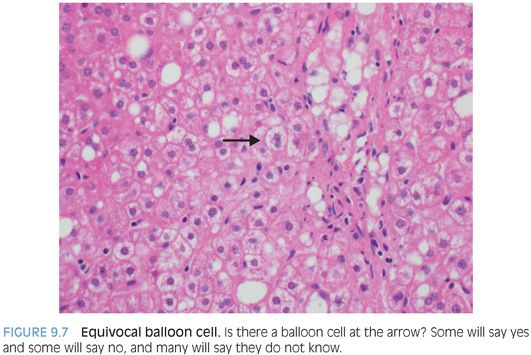

There are many balloon cells that all pathologists will agree on; sometimes, these are called classic balloon cells. However, there are many putative balloon cells, perhaps even more frequent than classic balloon cells, which are truly in the “eye of the beholder” (Fig. 9.7). This latter group of possible ballooned hepatocytes will even split a group of experienced liver pathologists into disagreeing camps. Some early work suggests immunostains may be helpful in this area,11 but currently, this area of equivocal balloon cells has not been properly sorted. For diagnostic purposes, it seems that sticking with classic balloon is the best approach at this time.

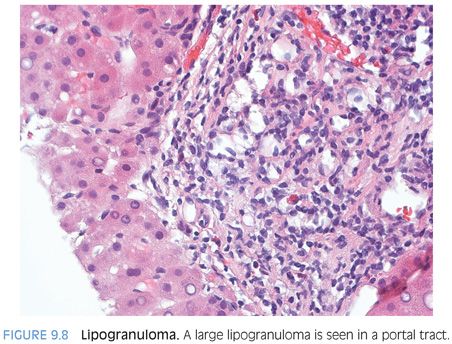

Lipogranulomas

Lipogranulomas are most commonly seen in portal tracts or in the central vein areas. They are composed of histiocytic aggregates with lipid droplets (Fig. 9.8). A small number of lymphocytes or eosinophils may also be present. Many of them will be associated with focal fibrosis,12 but they are not associated with fibrosis progression per se. Many lipogranulomas are associated with mineral oil,13 a common food additive, whereas others are seen in association with fatty liver disease or chronic hepatitis C.12 In cases of chronic hepatitis C, they are most commonly present in biopsy specimens that show coexisting steatosis.

Megamitochondria

Megamitochondria are commonly seen in fatty liver disease. Megamitochondria are small eosinophilic structures in the hepatocyte cytoplasm that can range in size from 1 to 6 µm. They can be single or multiple, and their shapes vary from round, to oval, to needle shape (Fig. 9.9). Their frequency in biopsy material tends to correlate with how hard you look for them, but they are easily found without much looking in about 15% of NAFLD cases.14 They are not specific for fatty liver disease and are seen in a wider variety of liver diseases. Overall, they are more common in steatohepatitis but are neither necessary nor specific for the diagnosis.

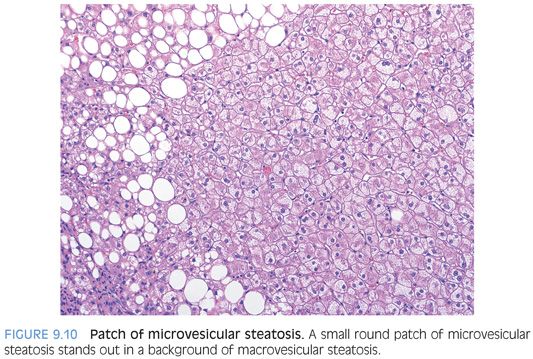

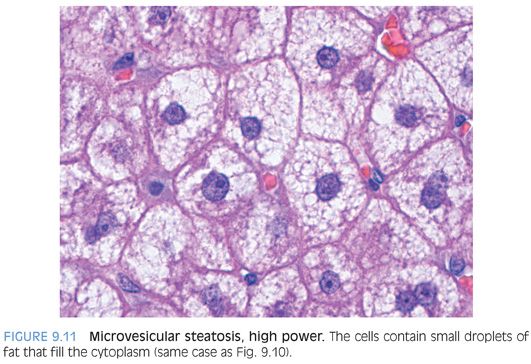

Patches of Microvesicular Steatosis

About 10% of cases of typical NAFLD will have small circumscribed patches of microvesicular steatosis (Figs. 9.10 and 9.11). These small patches are more commonly seen in cases of moderate to marked steatosis with active steatohepatitis.15 They are also more common in cases with advanced fibrosis.15 Outside of these correlates, their pathogenesis and clinical significance is unclear. In terms of surgical pathology, it is important to not over interpret these findings as indicating a true microvesicular steatosis pattern.

Patches of Hepatic Glycogenosis

Small contiguous patches of hepatocytes can show cytoplasmic rarefaction because of glycogen accumulation. This finding can be seen in a variety of different liver diseases, and currently, it is unclear if this finding is more common in fatty liver disease. The most important point is to not interpret this focal finding as glycogen hepatopathy, which has similar findings at the individual cell level but is a diffuse process associated with poorly controlled glucose.

Glycogenated Nuclei

Glycogenated nuclei are common in steatosis, seen in approximately 45% to 65% of cases.14,16 The hepatocytes with glycogenated nuclei tend to cluster (eFig. 9.10), but there can also be single scattered hepatocytes with the same change. Overall, glycogenated nuclei correlate with diabetes but have little or no correlation with the degree of fat.17

Aberrant Central Arteries

In cases of advanced fibrosis, scarred central veins can have ingrowth of branches of the hepatic artery.18 These scarred and arterialized central veins can mimic portal tracts because both an artery and vein are present, and this can make histologic orientation more difficult (eFig. 9.11). Careful evaluation of the overall biopsy typically can resolve this issue. These abnormal branches of the hepatic artery can be seen in both alcoholic and NASH with advanced fibrosis.

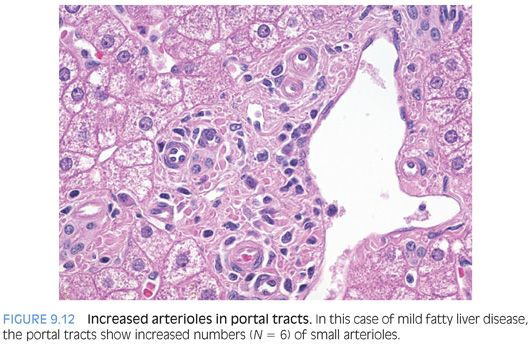

If you look carefully, a subset of cases of NAFLD also has increased arterioles in the portal tracts (Fig. 9.12). The significance and frequency of this finding is unclear. Anecdotally, these seem to be more prominent in cases of sleep apnea, and it is interesting to speculate they may serve as a marker for chronic intermittent hypoxia of the liver. However, their true meaning awaits future study.

Metabolic Syndrome without Fat

Based on liver biopsies obtained during bariatric surgery, approximately 10% of patients with the metabolic syndrome will have no fat in the biopsy, despite having a large wedge biopsy specimen. This subgroup of patients has not been well characterized in the published literature, but there is no clear difference in age or gender compared to those individuals with fat in their biopsies. In cases that lack fat, the biopsies generally show mild portal chronic inflammation with rare portal tracts that approach moderate chronic inflammation. The lobules show no or minimal chronic inflammation, and fibrosis is generally absent.

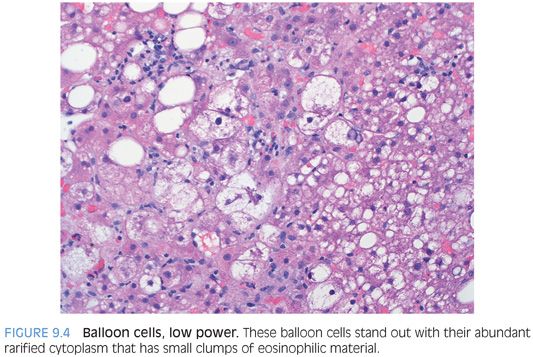

DIFFERENTIATING STEATOSIS FROM STEATOHEPATITIS

There is a lot of emphasis on separating steatosis from steatohepatitis on liver histology because steatosis generally has little or no risk for fibrosis progression, whereas approximately 30% of cases of steatohepatitis will develop some fibrosis and 15% will develop cirrhosis.19 How is this distinction best made? There is clearly a histologic continuum between the two, but within this continuum, most cases still will fall into categories of either steatosis or steatohepatitis. In the following text, some areas of controversy will be discussed, but these controversial areas are a relatively minority component compared to the majority of cases that can be comfortably and reproducibly diagnosed by histology.

The core notion of separating steatosis from steatohepatitis is as follows: Both should show at least mild fat, but steatohepatitis should also show “active” or “ongoing” injury. Both can have fibrosis. Thus, diagnosing steatohepatitis really focuses on the notion of identifying active or ongoing injury. It is generally agreed that the active injury can have elements of balloon cells (plus or minus Mallory hyaline), lobular hepatitis, and apoptosis. But there are different opinions among expert pathologists over the exact composition needed for active injury. Some authors insist on the presence of balloon cells for the diagnosis of steatohepatitis. This works well in many cases, because biopsies with readily identified classic balloon cells will typically also have lobular hepatitis and apoptotic bodies. However, as mentioned earlier, there are some cases where one expert pathologist will absolutely commit to a given cell as having balloon cell changes, whereas other expert pathologists will find that exact same cell to not have definite ballooning. Furthermore, some cases may have no clear balloon cells but have sufficient lobular hepatitis and apoptotic bodies to make a reasonable pathologist uncomfortable with a diagnosis of only steatosis. These areas of generally uniform agreement and clear disagreement are summarized in Table 9.1. There is no experimental evidence that satisfactorily resolves the question of what are the minimum changes needed for a diagnosis of steatohepatitis, so the author believes that the most prudent course at this time is to use a constellation of findings for active injury: If there are classic balloon cells present, then diagnose steatohepatitis; if there are no classic balloon cells present but there is more than the usual minimal to patchy and mild lobular hepatitis of steatosis, then also diagnose steatohepatitis. If there are no balloon cells and only minimal to patchy mild lobular inflammation, then diagnose steatosis.