16 Faecal incontinence (leakage of stool)

Case

Mrs C.B. is a 58-year-old woman who presents complaining of worsening faecal incontinence over 2 years. She had noticed soiling of her underclothes two or three times per week and needed to wear a pad. This occurred particularly if the stool was loose but also occasionally with formed stool. She also had incontinence to flatus. The incontinence took the form of urgency, with inability to defer defecation and soiling if she did not make the toilet in time. At other times there was involuntary seepage without awareness.

Definitions

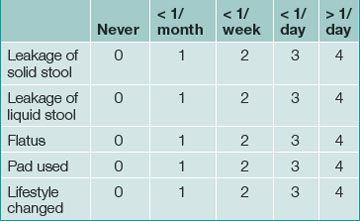

Continence is defined as the ability to control the onset of rectal evacuation. Minor incontinence refers to mucus discharge or incontinence of liquid or solid stool less than once per week. Major incontinence is loss of liquid or solid stool more than once a week, or sufficiently frequently to be causing social embarrassment for the patient. A more objective numerical continence scoring system, taking into account the exact frequency and nature of incontinence, is now commonly used in specialist centres and a simplified version is helpful for routine clinical assessment (Table 16.1).

Table 16.1 Simplified Wexner scoring system for faecal incontinence (0–20): 0 = normal continence, 20 = severe incontinence

History

The causes of faecal incontinence are summarised in Box 16.1. A good history about the nature of the incontinence will often provide clues about the cause. Physical examination and tests of anorectal function will determine whether the sphincter is normal, and will identify the likely pathology in most cases. The three most common causes of faecal incontinence requiring surgical treatment are rectal prolapse, sphincter trauma and neurogenic incontinence. These conditions account for the majority of patients who suffer severe longstanding symptoms.

The features in the history that need to be established in these patients are:

Examination

The patient is examined in the left lateral position with the hips flexed to allow the examiner good access to the perineum and anal region. The area is inspected for soiling, and for excoriation of the perianal skin as evidence of chronic irritation secondary to incontinence. Any external prolapse at the anus (Box 16.2) and an asymmetrical sphincter caused by trauma and perianal scarring are looked for.

Digital anorectal examination is carried out next and the resting tone (produced by the internal sphincter) is noted. The functional length of the anal canal in centimetres should be estimated. The strength of the pelvic floor muscles is assessed by pressing posteriorly and laterally. External sphincter strength is assessed by asking the patient to contract the sphincter and, thereafter, to cough. A shortened, weak sphincter is found in neurogenic incontinence. A weak sphincter of normal length is caused by a sphincter defect due to trauma. The sphincter is examined circumferentially between the thumb and index finger and a defect may be palpable.

Proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy

At proctoscopy, anal mucosal prolapse and haemorrhoids can be diagnosed. Sigmoidoscopy is essential to exclude rectal pathology including proctitis and rectal tumours (Ch 22). The patient is asked to strain down on the sigmoidoscope and prolapse of the rectal wall can often be detected in this way.

Physiological Anorectal Assessment

Physiology of continence

Normal continence depends on an interaction of the following factors.

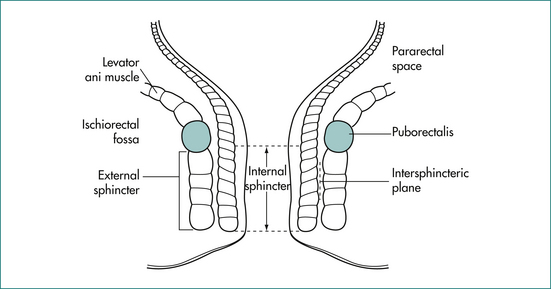

The anal canal is surrounded by a muscular tube that produces a high-pressure zone exceeding the pressure in the rectum. The sphincter contains two layers (Fig 16.1): an inner layer of involuntary smooth muscle (internal sphincter) and an outer layer of skeletal muscle (external sphincter). The internal sphincter is a distal continuation of the circular muscle of the rectum and is in a state of constant contraction, maintained by a process of intrinsic muscle stimulation. Relaxation of the muscle occurs during defecation, mediated by a local neural reflex within the wall of the anorectum in response to distension of the rectum by the faecal bolus, as well as by extrinsic autonomic control via the presacral sympathetic nerves. The external sphincter is under voluntary control but also contracts involuntarily in response to an increase in intraabdominal pressure via a spinal reflex through the anterior horns of the S2–S4 spinal segments and the Onuf nucleus in the spinal cord.

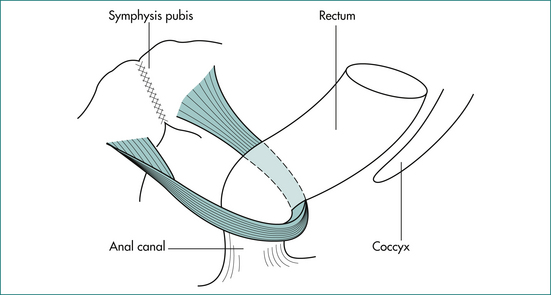

The puborectalis muscle lies immediately above the external sphincter and forms a muscular sling behind the anus (Fig 16.2). It supports the anus and produces the anorectal angle, which is felt posteriorly at the upper end of the anal canal when doing a rectal examination.

Figure 16.2 The puborectalis muscle forms a sling behind the junction of the anus and rectum.

From Anderson JE, ed. Grant’s Atlas. 7th edn. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1978, with permission from the publisher.

The anal mucosa contains an abundance of sensory nerve endings. Spontaneous relaxation of the upper part of the internal sphincter occurs intermittently to allow the anal mucosa to ‘sample’ the contents of the rectum (the sampling reflex). This allows us to normally distinguish flatus from stool in the rectum.

Diagnostic tests

Anorectal manometry

Pressure in the anus and rectum is measured using a narrow diameter multichannel catheter. Each channel is perfused with water and connected to a pressure transducer and digital recording apparatus; sequential channels open at 0.75 cm intervals from the tip of the catheter (Fig 16.3). The pressure at rest reflects the strength of the internal sphincter, and pressure during voluntary contraction of the muscles is a measure of the external sphincter strength (Fig 16.4). Relaxation of the internal sphincter is tested by inflating a balloon positioned in the rectum at the tip of the manometry catheter, while recording anal pressure. Manometry is a very useful test because it defines which muscle is affected in a patient with sphincter weakness. It also demonstrates that sphincter function is normal in a patient whose incontinence is due to diarrhoea or excessive colonic propulsion, or due to a local anal condition such as haemorrhoids and, hence, confirms that sphincter weakness is not the cause of the incontinence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree