Introduction

Laparoscopic and robotic-assisted minimally invasive surgery has become widely adopted based on multiple well-demonstrated benefits, including reduced complications, readmissions, postoperative pain, and length of stay. However, these approaches have also introduced new questions and challenges, including how to safely exit an abdomen that was entered in a minimally invasive fashion. Although wound complication rates are lower with laparoscopic surgery compared with an open approach, they may occur in as many as 21 per 100,000 cases. Complications include hematoma, infection, dehiscence, and trocar site hernia. Bowel injuries can also rarely occur during port site closure. Thus, this final and often seemingly minor step of any minimally invasive surgery certainly warrants specific attention.

Port closure

The general steps of exiting the abdomen typically include a final inspection of the operative site and field overall, port removal, evacuation of pneumoperitoneum, and port closure. There remains some debate regarding which port sites necessitate closure. Some studies have found trocar site hernia rates as high as 2.8% with bladed trocars; however, with increasing preference for blunt-tip or dilating trocars, more recent studies have demonstrated rates as low as 0%–1.2%. Many texts recommend closing fascia for all ports 10 mm or larger, which is based largely on a survey from 1994 that demonstrated that only 13.7% of trocar site hernias occurred at the port sites smaller than 10 mm. However, there have since been multiple studies that have demonstrated the safety of foregoing fascial closures and port sites up to 12 mm when using bladeless trocars. , , Based on these conflicting data, we can make no definitive recommendation as to which port sites require closure. A risk-based approach has also been recommended, but these data are also mixed and inconclusive. Midline or umbilical ports have been associated with a higher risk of hernia in multiple studies, though this association is confounded by specimen extraction, which is often performed at these sites. Obesity, poor nutritional status, diabetes, and prior surgery have all been suggested but not confirmed in any large and rigorous studies. It is also often recommended that all port sites be closed in pediatric patients. Ultimately, the decision to close fascia remains at the surgeon’s discretion based on case-specific and patient-specific factors.

Methods of port closure

If the decision is made to close the fascia at a port site, there are multiple techniques that can be employed, including open or laparoscopic closure using any one of a multitude of devices or instruments.

Open closure

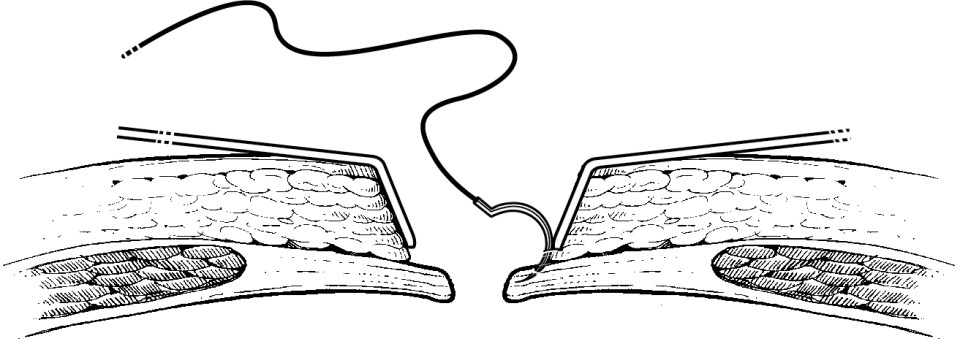

Open or hand-sewn closure offers the advantage of direct fascial visualization in patients with relatively minimal subcutaneous fat. This method of closure can also be convenient if abdominal access was obtained via the Hassan technique and stay sutures are already in place along the fascial edges. Open closure is also typically employed for any large defects such as specimen extraction sites and is performed in the standard fashion as would be done in an open surgical case. For port sites or relatively small extraction sites, we find it useful for the assistant to insert one S-retractor or Army-Navy retractor into the peritoneal cavity, which is used to lift the abdominal wall away from the underlying viscera while the other retractor is used to expose the fascial edge. A needle with a relatively small radius, such as a GU needle, is typically used ( Fig. 12.1 ).

Disadvantages of this technique include the possible increased risk of wound infection, dehiscence, and ascitic fluid leak as well as prolonged procedure time. It is also particularly difficult in obese patients given the depth of the fascia from the skin and the small incision used for port insertion.

Laparoscopic closure devices

In contrast to open closure, a number of closure devices are available that can be used while insufflation is maintained and closure is performed with direct laparoscopic visualization. Although there are many devices that can be utilized, the general principal is to guide to the closing suture through the fascia and peritoneum under visualization to ensure there is no abdominal visceral injury. The benefits of this technique include theoretically lower risk of visceral injury, improved efficiency, and the ease in which it can be performed in obese patients in whom fascial visualization would otherwise be difficult.

Although this is not an exhaustive list, commonly utilized devices include the reusable Berci fascial closure instrument (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) and the disposable Carter-Thomason (CooperSurgical, Trumbull, CT), Endo Close (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), Omniclose (Unimax, New Taipei City, Taiwan), and Weck EFx Shield (Teleflex, Morrisville, NC) devices.

The Carter-Thomason CloseSure System ( Fig. 12.2 , ![]() ) consists of two components: a 5-mm or 10/12-mm cone-shaped pilot guide and a single-action hinged-jaw suture passer that is open or closed using a thumb handle. After trocar removal, the closure technique begins with insertion of the cone-shaped guide into the port site. The suture passer is loaded and introduced into the guide channel, which directs it through the fascia and peritoneum under direct laparoscopic visualization. The suture is guided toward the opposite side of the fascial defect to facilitate the second pass. The same process is then repeated through the opposite side of the fascial defect, and the free hanging suture within the peritoneum is grasped and pulled out. The sutures then hand-tied, and adequate closure is verified laparoscopically.

) consists of two components: a 5-mm or 10/12-mm cone-shaped pilot guide and a single-action hinged-jaw suture passer that is open or closed using a thumb handle. After trocar removal, the closure technique begins with insertion of the cone-shaped guide into the port site. The suture passer is loaded and introduced into the guide channel, which directs it through the fascia and peritoneum under direct laparoscopic visualization. The suture is guided toward the opposite side of the fascial defect to facilitate the second pass. The same process is then repeated through the opposite side of the fascial defect, and the free hanging suture within the peritoneum is grasped and pulled out. The sutures then hand-tied, and adequate closure is verified laparoscopically.