Esophageal Cancer: Pathology

Susan C. Abraham

Tsung-Teh Wu

Esophageal cancer is an aggressive disease with a poor prognosis. In 2005, it is estimated that there will be approximately 14,000 new esophageal cancers, and an equal number of cancer deaths are expected (1). The dismal prognosis of esophageal carcinoma is mainly due to late diagnosis with presentation at an advanced stage. The 5-year survival is approximately 14% for all stages of esophageal carcinoma (1). Histologically, esophageal cancer can be subclassified into epithelial and nonepithelial tumors. Similar to other regions of the gastrointestinal tract, carcinomas are the most common esophageal cancer with more than 90% of cancers representing either squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or adenocarcinoma. SCC is the most common malignant esophageal cancer worldwide, especially in Asian populations and in parts of Africa and Europe. In the United States, SCC accounted for more than 90% of all esophageal cancers in 1960, but the pattern of esophageal cancers has changed since then (2). The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinomas, including those of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), has increased markedly in Western countries and in the United States, now constituting almost 50% of all esophageal cancers (3,4).

Esophagectomy has been the mainstay of therapy for localized esophageal carcinomas. Their prognosis is influenced by pathological features, including depth of tumor invasion, lymph node status, and completeness of resection as determined on the resected esophagus (5,6,7). Multimodality strategies using preoperative chemoradiation followed by esophagectomy are frequently used to treat locoregional esophageal carcinomas (8), based on the assumption of early therapy of micrometastasis, reduced local relapse, and a higher rate of curative surgery after chemoradiation despite equivocal benefits in randomized trials (9,10,11,12,13). The prognosis appears to be predicted by pathological stage determined on the resected esophagus after preoperative chemoradiation (14). In patients with high-grade precursor lesions (squamous or columnar epithelial dysplasia) or superficial esophageal carcinomas, noninvasive therapeutic modalities such as endoscopic mucosal resection have become attractive alternatives to esophagectomy. Pathological evaluation, including diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma by endoscopic biopsy or evaluation of detailed pathological features in esophagectomy or endoscopic mucosal resections, is essential for treatment planning and communication with patients regarding prognosis.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Pathogenesis

SCC of the esophagus affects males more commonly than females. The pathogenesis of SCC is multifactorial and may vary among different regions of the world (15). The most significant contributing factors include tobacco and alcohol use, food and water contamination with nitrates and nitrosamines, and various vitamin deficiencies. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection has been found in esophageal SCC by identification of HPV DNA either by in situ hybridization or polymerase chain reactions with a variable rate between 0% and 66% (16,17,18). It is more consistently detected in China but generally absent in SCC arising in Western countries. There are also several predisposing conditions for the development of SCC, including achalasia, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, esophageal strictures secondary to lye or acid ingestion, and the autosomal dominant disease tylosis palmaris et plantaris. Esophageal SCC also develops in up to 60% of patients surviving a previous head and neck carcinoma associated with smoking (19). In addition, distal esophageal SCC can also occur in regions of Barrett esophagus, a condition more predisposed to develop adenocarci noma (20).

Pathological Features

Gross Pathology

SCCs are located predominantly in the middle (50%–60%) and lower (30%) esophagus, and only infrequently in the upper (10%–15%) esophagus (21). The gross appearance of esophageal SCC varies according to the stage of disease at the time of diagnosis. Superficial SCC—defined as tumor invading only the mucosa or submucosa irrespective of the presence of lymph node metastasis (22)—accounts for 10% to 20% of resected SCC in Japan but is much less frequently reported in Western countries. The gross appearance of superficial SCC can be polypoid, plaquelike, depressed, or grossly inconspicuous (23). Superficial SCC can also present with multiple tumors in up to 14% to 31% of cases (24,25,26).

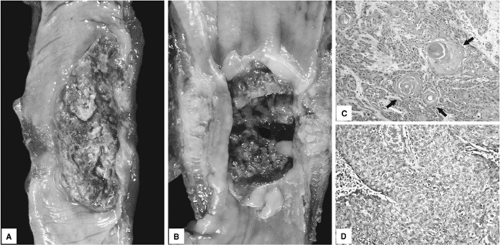

Most esophageal SCCs are diagnosed at an advanced stage, and these tumors can be classified into three major gross patterns: fungating, ulcerating, or infiltrative (Fig. 16.1A, B) (21). The fungating pattern is characterized by exophytic or polypoid growth and is the most common type (60% of cases). In contrast, tumors with the ulcerating pattern (25% of cases) typically have intramural growth with a central ulceration. The infiltrative pattern is the least common type (15% of cases), containing intramural tumor growth but only a small mucosal defect. The gross appearance of advanced SCC, however, is not a significant prognostic factor. The gross appearance can also change substantially after preoperative adjuvant therapy depending on individual tumor response to treatment.

Microscopic Pathology

Tumor Differentiation

Esophageal SCC has a range of differentiation and can be classified into well, moderately, and poorly differentiated based on the degree of squamous differentiation. In well-differentiated tumors, the epithelial tumor nests have mild nuclear atypia and cellular pleomorphism, distinct intercellular bridges, prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm representing individual cell keratinization, and squamous pearl formation (Fig. 16.1C). Moderately differentiated tumors typically have higher degrees of cellular atypia and nuclear pleomorphism and a lesser degree of keratinization as compared to well-differentiated tumors; moderately differentiated SCC accounts for a majority (two-thirds) of esophageal SCC. Poorly differentiated SCCs tend to grow in solid sheets or single cells, cytologic atypia and nuclear pleomorphism are more pronounced, and keratinization is less appreciable (Fig. 16.1D).

The distinction between poorly differentiated SCC and adenocarcinoma can occasionally be subtle. Immunohistochemical labeling for cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 and p63—markers for squamous differentiation positive in up to 75% to 93% of SCC (27)—can be used to support the diagnosis of poorly differentiated SCC. The presence of poor tumor differentiation may be a prognostic factor, but its significance remains controversial (28,29). Focal neuroendocrine or glandular differentiation, tumors with mixed SCC and adenocarcinoma (adenosquamous carcinoma), or mixed SCC and neuroendocrine carcinoma can also occur (30,31).

Tumor Spread and Metastasis

The depth of tumor invasion (T stage) correlates well with the presence of lymphovascular invasion and regional lymph node metastasis (N stage) (6). Positive lymph nodes are present in 50% to 60% of esophagectomies for locally advanced SCC (32). The carcinoma, in fact, can invade into intramural lymphatic vessels at an early stage of disease. In superficial (T1) esophageal SCCs, the risk of lymph node metastasis is lower than in advanced SCCs and has been shown to depend on the depth of invasion. Tumors invading only into lamina propria (intramucosal carcinomas) have lymph node metastasis in only 5% of cases, whereas tumors invading submucosa have a 35% risk of lymph node involvement (21,33).

Occurrence of intramural metastasis, manifested by intramural or submucosal lymphatic spread with the establishment of secondary tumor deposits, has been found in 11% to 16% of resected esophageal SCCs and is associated with advanced stage and poorer survival (24,34). Frozen section evaluation of the proximal esophageal resection margin for the presence of submucosal lymphatic spread is justified to ensure curative resection. The most frequent sites of distant metastases are lung and liver, present in up to 50% of autopsied cases (35). Other organs such as bones, adrenal glands, and brain are less frequently involved. Disseminated tumor cells identified by cytokeratin immunolabeling in bone marrow have been detected in 40% of resected esophageal SCC (36), and may account for poor survival and high recurrence rate despite curative surgery.

Variants of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Basaloid Squamous Cell Carcinoma

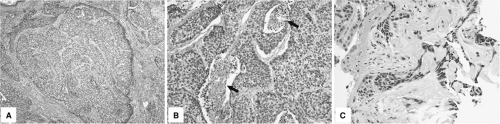

Basaloid SCC is an uncommon but distinct variant of esophageal SCC that affects predominantly older men (37). Basaloid SCCs typically present as bulky fungating tumors with ulceration and stricture. Histologically, these tumors are composed of large solid or compact tumor nests with hyperchromatic nuclei, scant basophilic cytoplasm, peripheral palisading, and central comedo-type necrosis (Fig. 16.2A, B). Foci of myxoid matrix and hyalinized stroma surrounding tumor nests and occasional small glandlike structures are also seen (Fig. 16.2 C). Basaloid SCCs are often associated with squamous dysplasia, invasive SCC, or islands of squamous differentiation.

Proliferation activity and apoptosis rate are higher than in classical SCC.

Proliferation activity and apoptosis rate are higher than in classical SCC.

Basaloid SCC needs to be differentiated from true adenoid cystic carcinoma of the esophagus—a rare and less aggressive subtype than basaloid SCC—and from high-grade neuroendocrine (small cell) carcinoma. Immunohistochemical labeling for S-100 and actin can be used to highlight the basal cells of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Basaloid SCC is positive for CK 5/6 but negative for neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin and synaptophysin, which are positive in neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Verrucous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare variant of SCC, histologically similar to verrucous carcinomas arising in other organ sites (38). An association with chronic esophagitis has been reported in one study (39). Grossly, these tumors have an exophytic, papillary, and cauliflowerlike appearance, and tend to grow large and involve the entire circumference of the esophageal wall before symptoms occur and a diagnosis can be made. Microscopically, the tumors are composed of large fronds of well-differentiated squamous epithelium with parakeratosis, hyperkeratosis, and minimal cytologic atypia mimicking benign squamous epithelium. They grow with an expansile or pushing border rather than the infiltrative pattern seen in classical SCC.

These deceptively benign histologic features make definitive diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma (usually >3 cm) versus large squamous papilloma (usually <3 cm) challenging for pathologists in endoscopic mucosal biopsy specimens. Careful endoscopic-pathological correlation is required. Esophageal verrucous carcinoma is a low-grade malignant neoplasm, which grows slowly and invades locally with only infrequent lymph node metastasis.

Sarcomatoid Carcinoma

This is a rare variant of SCC also known as carcinosarcoma, polypoid carcinoma, and spindle cell carcinoma (40,41). This tumor has a polypoid gross appearance and may grow to a large size averaging 6 cm in diameter. Histologically, sarcomatoid carcinoma is characterized by the presence of a biphasic pattern with both carcinomatous and spindle cell (sarcomatoid) components. The carcinomatous component is typically well to moderately differentiated SCC; infrequently, adenocarcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma has been described. The sarcomatous component is more variable, ranging from rather innocuous spindle cells to high-grade sarcoma with pleomorphic, bizarre giant cell cells and numerous mitoses. Maturation and differentiation into bone, cartilage, or skeletal muscle can also be present in the sarcomatoid component.

The sarcomatous component appears to arise from the carcinomatous component by metaplasia, judging from immunohistochemical and electron microscopic analyses (42). However, carcinosarcoma arising from two distinct malignant clones has been suggested by a recent molecular analysis that sarcomatous and carcinomatous components contain different genetic alteration profiles in 13 cases (41). The prognosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma appears to be more favorable than classical SCC due to the fact that sarcomatoid carcinoma has a luminal polypoid exophytic growth pattern. However, lymph node metastasis is present in 40% to 50% of the cases at the time of diagnosis, and in a stage-by-stage comparison, the prognosis is similar to SCC (40,41).

Precursor Lesion: Squamous Dysplasia (Intraepithelial Neoplasia)

Esophageal SCC is believed to arise from a multistage process through progression of a premalignant precursor lesion (squamous dysplasia or squamous intraepithelial neoplasia) into invasive SCC (43). Squamous dysplasia was present adjacent to invasive SCC in 14% to 20% of resected SCC in one study (44) and 60% to 90% in another study (25). Squamous dysplasia is commonly present in patients at high risk for developing SCC (44). Dysplasia is defined by the presence of cytologically and architecturally neoplastic epithelial cells confined within the mucosa. Squamous dysplasia can be further classified using a two-tiered system as either low-grade or high-grade dysplasia (25).

Grossly, squamous dysplasia appears erythematous, friable, and irregular in shape. In some cases, erosions, plaquelike lesions, nodules, or even a normal appearance can also be seen by endoscopic examination (44). Mucosal spread of Lugol’s iodine can be used to highlight the dysplastic lesions to increase the yield of biopsies in surveillance of high-risk patients (45).

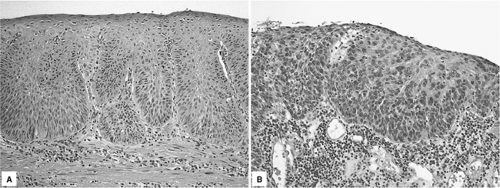

Histologically, low-grade squamous dysplasia is characterized by neoplastic squamous epithelial cells with irregular and hyperchromatic nuclei and increased nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio that are confined to the lower half of the epithelium (Fig. 16.3A). In high-grade squamous dysplasia, a greater degree of cytologic atypia is present with involvement of the upper half of the epithelium (Fig. 16.3B). Dysplasia involving esophageal submucosal gland ducts can occasionally occur and needs to be distinguished from invasive SCC (46). In this two-tiered grading system, carcinoma in situ is included in the high-grade dysplasia category and carries the same clinical implication (21).

Patients with squamous dysplasia have an increased risk of developing invasive SCC. Regression of low-grade squamous dysplasia can occur (and is more frequent than regression of high-grade dysplasia), but progression to high-grade dysplasia occurs in 15% of patients (47). In prospective follow-up studies conducted in China, invasive SCC arose in 9% of patients with squamous dysplasia over a 15-year period (48) and in 30% of patients with high-grade dysplasia over an 8-year period (47). The high incidence of SCC arising in patients with high-grade squamous dysplasia warrants close endoscopic surveillance for early diagnosis of invasive SCC or, alternatively, removal of visible lesions by endoscopic mucosal resection.

Neuroendocrine Carcinoma

Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors (well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms) of the esophagus are rare. They can present as isolated tumor nodules or be associated with adenocarcinoma (49). The histologic features are the same as in carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract in general. Carcinoid tumor is composed of solid nests of relatively monotonous tumor cells with “salt and pepper” nuclear chromatin that express neuroendocrine differentiation by immunohistochemical labeling for chromogranin or synaptophysin.

Small Cell Carcinoma (Poorly Differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma)

Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas constitute only 1% to 2% of all esophageal cancer (50). They are frequently located in the lower esophagus and tend to form large exophytic masses. Small cell carcinomas of the esophagus are histologically similar to small cell carcinomas of the lung. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of sheets or nests of small round to oval tumor cells with scant cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with molding. Foci of squamous differentiation or glandular differentiation have been reported in as many as 50% of esophageal small cell carcinomas (51).

Esophageal small cell carcinomas are aggressive malignancies, and their prognosis is poor, with a median survival of only 6 to 12 months (50). As previously mentioned, distinction between small cell carcinoma and basaloid SCC is important for choosing appropriate preoperative neoadjuvant therapy.

Adenocarcinoma

Pathogenesis

Adenocarcinoma has become the predominant histologic type of esophageal carcinoma in Western countries due to a marked increased rate of adenocarcinoma in the distal esophagus and esophagogastric junction (EGJ) since the 1970s (3,4). A majority (>95%) of esophageal adenocarcinomas arise in association with Barrett esophagus, a precursor of adenocarcinoma. Barrett esophagus is characterized by the presence of intestinal metaplasia (goblet cells) in the tubular esophagus and develops in approximately 10% of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (52). Patients with Barrett esophagus have a 125-fold increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma as compared to the general population (53); however, this risk may be overestimated as shown in more recent studies (54,55,56,57).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree