Esophageal Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, and Prevention

Evan S. Dellon

Nicholas J. Shaheen

Esophageal malignancies are relatively uncommon in the United States, and because they are often diagnosed at an advanced stage, prognosis is poor. These cancers have attracted attention due to changing epidemiology, ongoing attempts to identify risk factors, and the large percentage of the population purportedly at risk for disease. This chapter focuses on the two major forms of esophageal neoplasm: squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus (ACE). The epidemiologies of these diseases are reviewed, issues pertaining to screening are discussed, and strategies for prevention are presented.

Epidemiology

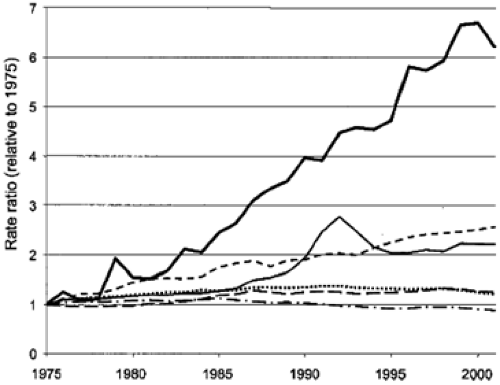

Worldwide, esophageal cancer is the eighth most common malignancy, responsible for approximately 462,000 new cases in 2002, with SCC as the most common pathological subtype (1). Although SCC was the predominant histologic form of esophageal cancer in the United States until the 1960s, the incidence of ACE has risen steadily since then (2). Various studies place the rate of increase of incidence at approximately 4% to 10% per year, with a total increase of 300% to 500% in that time frame (3,4,5,6,7), a rate greater than seen in any other type of cancer (Fig. 14.1). The underlying cause of this shifting epidemiologic pattern is not known, but proposed contributing factors include the current epidemic of obesity, increasing use of endoscopy leading to better detection, changing demographics of the U.S. population, alteration in the prevalence of other risk factors, and perhaps even widespread treatment of Helicobacter pylori (5,6). Although a rapid change in epidemiology is not suggestive of an underlying genetic etiology, host factors are also likely of importance for these neoplasms (see Chapter 15). Several analyses have assessed possible factors that might explain this increase, including misclassification bias and increasing endoscopy utilization. After controlling for numerous factors, the increasing incidence of ACE does not appear to be explained by these biases (8,9).

Despite these impressive changes in histologic subtype, the overall number of esophageal malignancies has only increased slightly in the United States because as the incidence of ACE has increased, the incidence of SCC has decreased. Overall, there were estimated to be 14,520 new cases of esophageal cancers in 2005, and esophageal cancer was responsible for 13,570 deaths (2). Although esophageal cancer was only the 19th most common cause of cancer in the United States (the most common gastrointestinal cancer was colorectal cancer, with an estimated 145,290 new cases in 2005), it was the sixth leading cause of cancer deaths in men, and the 16th cause in women. The 5-year survival rate of 14% is worse than most other malignancies, with the exception of pancreatic and hepatobiliary cancers, and has improved only trivially since the 1970s and 1980s (2,10). Of new diagnoses of esophageal cancer in the United States in 2005, more than half were ACE (compared with approximately 5% prior to 1970); the majority of the remainder of cancers were SCC (3,4,6,11). Risk factors and other issues pertaining to these cancers are discussed in separate sections of this chapter. Other uncommon benign and malignant neoplasms of the esophagus comprise less than 7% of all esophageal tumors (12); several of these are discussed in Chapter 16.

Risk Factors for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus

Geographic

There are multiple well-established risk factors for esophageal SCC (Table 14.1). Worldwide, there is a marked discrepancy in incidence by geographic region (1,13). For example, in the United States and several Western European countries, rates are relatively low (1–5 cases per 100,000). In contrast, in parts of Asia, India, and Africa, the rates can be substantially higher (50–200 cases per 100,000). Although a particular geographic area may be a proxy for genetic or environmental factors, a person’s country of origin may nonetheless be helpful in stratifying risk.

Demographic

Similar to other cancers of the digestive tract, the incidence of SCC of the esophagus increases with age, and the mean age of diagnosis is in the seventh and eighth decades of life (14). Males are two to four times more likely to be affected by SCC than females, and African Americans have four to five times the risk of Caucasians (3,15). The risk for other nonwhite ethnic minorities has not been well delineated. Poor socioeconomic status is also independently associated with increased risk of SCC of the esophagus (15).

Tobacco and Alcohol

Multiple studies have found that exposure to tobacco and alcohol is strongly associated with an increased risk of SCC in a dose-dependent manner, and when present together, the risk increases synergistically (16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23). For both substances, relative risk increases are in the 2- to 10-fold range, but some reports

find increases in risk of up to 25-fold. In addition, although some studies suggest that the type of alcohol, such as hard liquor, may be more significant (16,19), others suggest that the total quantity of alcohol ingested is the most important factor (22). Interestingly, head and neck cancers, which are also associated with tobacco and alcohol use, demonstrate an association with esophageal SCC (24).

find increases in risk of up to 25-fold. In addition, although some studies suggest that the type of alcohol, such as hard liquor, may be more significant (16,19), others suggest that the total quantity of alcohol ingested is the most important factor (22). Interestingly, head and neck cancers, which are also associated with tobacco and alcohol use, demonstrate an association with esophageal SCC (24).

Table 14.1 Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

Diet and Nutrition

Dietary factors may explain some of the wide geographic variation in the incidence of esophageal SCC. Foods that contain N-nitrosamines are associated with increasing rates of SCC of the esophagus (25,26). These may not only cause direct toxicity to esophageal mucosa but may also injure DNA over time. Chronic chewing of the Betel nut, a practice in Asia, has been associated with increased SCC (27), as has the Iranian custom of drinking very hot beverages (28). General malnutrition; deficiencies of selenium and zinc; and deficiencies of vitamins A, C, E, folate, riboflavin, and B12 have also been associated with esophageal SCC (29,30,31,32,33,34,35).

Nonmalignant Esophageal Disease

Underlying disease processes of the esophagus can predispose to cancer. It has been well established that over time, patients with achalasia have between a 15- and 30-fold increased risk of developing SCC of the esophagus (36,37,38). The mechanism of this association is not understood. In addition, caustic ingestions (e.g., of lye) have been shown to increase the risk of esophageal SCC (39,40). Radiation exposure, either environmental or medical (41,42,43); Plummer-Vinson syndrome (44); and Zenker diverticula (45) have also been associated with SCC.

Infections

Other

Tylosis palmaris is a rare autosomal dominant condition characterized by hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. Patients with this disorder are at high risk for development of esophageal SCC (48,49). Because rates have been reported as high as 50% at the age of 45 and 95% at the age of 65, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends that patients with this condition be screened with upper endoscopy starting at age 30 (50,51).

Risk Factors for Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus

Demographic

The risk factors for ACE are distinct from those for esophageal SCC (Table 14.1). Although increasing age, with a mean onset in the seventh and eighth decades of life, and a male predominance are similar to SCC of the esophagus, the demographic similarities end there (3,4,5,6,7,11). In general, ACE is approximately five times more common in Caucasians than in African Americans, and the association with socioeconomic status seen in SCC is not found in ACE. However, regional variation of ACE in the United States has been described (52). In addition, there does not appear to be a strong heritability, although host factors likely do play a role (53,54).

Obesity

Numerous studies have found that increasing obesity, as measured by body mass index, is a risk factor not only for acid reflux and Barrett esophagus but also for development of ACE (55,56,57,58). Further exploration of this relationship suggests that central or visceral obesity may modulate this effect.

Acid Exposure

As both a pathogenic mechanism and a risk factor, increased acid exposure is well recognized to play a role in ACE. Chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been shown to increase the risk of ACE both in case-control studies and in a recent meta-analysis (59,60,61,62). Although this is an important risk factor, it has been shown that approximately 40% to 50% of patients diagnosed with ACE do not have pre-existing reflux symptoms (59,60). Similar to associations seen in GERD, data suggest that medications such as nitrates, aminophylline, anticholinergics, and benzodiazepines, which lower the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, may be linked to ACE (63,64). Finally, H. pylori does not appear to be an independent risk factor; in fact, some data suggest that H. pylori infection may actually be protective against the development of ACE.

Barrett Esophagus

Barrett esophagus (BE) remains the most significant and widely studied risk factor for ACE. Initially described in the 1950s (65), BE is defined today by a combination of endoscopic and histologic findings. Suspected on endoscopy as tongues of salmon-colored mucosa in the distal esophagus that replace the normal squamous esophagus epithelium and displace the Z-line cephalad from the gastroesophageal junction, the diagnosis is confirmed by demonstrating specialized (or intestinalized) metaplasia with the presence of goblet cells on histologic examination (66,67). It is believed that the majority of adenocarcinomas arise in areas with Barrett mucosa, and that there is likely a pathway by which metaplasia progresses first to dysplasia, and then to carcinoma (68,69,70,71) (see Chapter 15). BE may be a response to chronic mucosal injury from GERD (72) and may also be associated with intra-abdominal obesity (73). GERD has also been linked to BE in numerous studies (74,75,76,77). However, new data demonstrate that many subjects do not have GERD symptoms but are found to have BE (78,79,80,81). Although environmental factors may interact with host factors to generate BE, specific genes have yet to be identified, and BE does not appear to have a strong heritable component (71).

The presence of BE independently increases the risk of developing ACE between 30 and 400 times (82,83,84,85,86,87), although a more accurate estimate is believed to be in the 30 to 60 range (11). The rate of progression from BE to ACE has been estimated in many investigations, and recent meta-analyses suggest that the rate of progression to cancer is approximately 0.5% per year (71,88). However, the risk is significantly higher in dysplastic BE. For example, in high-grade dysplasia (HGD) the rate can be 10% to 30% per year (69,71,89,90). In addition, surgical series show that in patients who undergo esophagectomy for HGD, there is a high rate of metachronous, previously undetected cancers in the resected specimen (70,91). But there is not an inexorable progression from BE to ACE. Several natural history and treatment trials show spontaneous regression from BE to normal squamous epithelium in some cases, as well as from HGD to low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and LGD to nondysplastic BE (72,92,93). Although this apparent regression may be partially explained by sampling error from diagnostic biopsy protocols (94), resolution of BE and/or dysplasia in some patients has been repeatedly demonstrated and is likely a true phenomenon. Finally, although BE is a strong risk factor for ACE, the presence of BE has not been definitively shown to increase mortality (95,96,97,98). Indeed, several studies have shown that patients with BE have the same life expectancy as those subjects without BE, and that, in many cases, even if BE progresses to esophageal AC, the eventual cause of death is not related to the cancer (97,98,99). Because ACE is a disease of the elderly, comorbidities can accumulate and compete with cancer as a cause of death in these subjects.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree