Diseases associated with esophageal eosinophilia

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia

Crohn’s disease

Infection (parasitic)

Celiac disease

Hypereosinophilic syndrome

Drug hypersensitivity

Achalasia

Vasculitis

Connective tissue disorder (scleroderma, dermatomyositis, polymysitis)

Pemphigus

Graft versus host disease

EoE is defined as a clinicopathologic immune and/or allergen-mediated disorder characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and a marked eosinophilic infiltrate on esophageal biopsy. Symptoms of esophageal dysfunction may mimic like GORD and this may coexist with EoE, which make it difficult for this condition to be differentiated from EoE. But treatment of GORD alone does not improve EoE. EoE represents the first cause of food impaction in young males and the second most common cause of chronic esophagitis (after GORD) [5] Currently, the gold standard for the diagnosis of EoE is the endoscopy with esophageal biopsies showing esophageal eosinophilia. A recent consensus document has proposed the presence of > 15 eosinophils (peak value) in at least one microscopic high-power field (HPF) of one or more esophageal biopsy specimens stained with hematoxylin and eosin after a course of PPI as necessary for establishing the diagnosis [6]. It is important to note, however, that the histological appearance of EoE can overlap with that of other conditions (Table 9.1) and that the diagnosis should rest on clinicopathological correlation rather than on a simple eosinophil count in isolation.

Since EoE was recognized as a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome, it has been described in industrialized countries, such as Europe, North America, and Australia [7]. Studies in the pediatric population have shown that the incidence of the disease is estimated at 4.4–9.5 cases per 100,000 person/year [8, 9] and the prevalence at 42.9–91 per 100,000 [10–13]. Over the past decade, emerging evidence confirm that the incidence of EoE has raised dramatically and has already approached that of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease [14, 15]. It remains to be clarified whether this is a true rise or it reflects the improved recognition and ascertainment of the disease.

EoE can present at any age, but it is more prevalent in childhood or during the third and fourth decade of life. Males (male to female ratio of 3:1), Caucasians, and patients with other associated atopic disorders are more prone to the disease [16]. Furthermore, it has been shown that familial predisposition can play an important role [17–19]. The estimated sibling risk recurrence ratio (RR) is approximately 80, which is much higher compared to other atopic diseases with inheritance patterns, as asthma [2, 20].

The symptomatology of EoE varies according to the age of presentation and can mimic GORD. Feeding difficulties, feed refusal, vomiting, and regurgitation , which can result in poor weight gain are usually the presenting symptoms in infants and toddlers. During childhood and adolescence, the disease presents with upper abdominal or retrosternal pain, dysphagia, and food impaction . Symptoms can rarely vary through the year, reflecting the seasonality of the allergen, when the allergy reaction is most likely directed to aeroallergens [21].

Over the past two decades, numerous studies have contributed to the understanding of the mechanisms of its pathogenesis. However, there are still fundamental questions to be answered. Research needs to shed light on whether EoE consists of one or more discrete subtypes or if it is a single condition with changes in expression over time [22]. Given our current understanding, the most likely driving factor for the process of the disease is an immune reaction to food or inhaled antigens. Taken this into account, elimination diets led to histological improvement and resolution of the eosinophilic eosinophilia and are considered as an effective treatment option [23–25]. However, not every patient’s clinical course suggests a causative food allergen [26].

Another question that has been posed in the literature is whether pediatric and adult EoE are two distinct disorders or the manifestation of a single entity. Many similarities and differences regarding the clinical presentation, the endoscopic findings, the response to treatment and the progression of the disease have been reported [27]. Adults most commonly present with dysphagia and have esophageal rings and strictures requiring dilation, whereas children tend to have plaques, furrows, and decreased vascularity on endoscopy [28]. To make things more complicated, it has been proposed that different phenotypes of the disease could result in divergent clinical presentation and outcomes [29–31]. However, given the current knowledge, pediatric and adult EoE share a common pathogenesis, similar histopathologic features, and constitute a single disease [5].

Pathophysiology

In terms of its pathophysiology, EoE has been characterized as a bulk of mysteries. Even though symptoms may differ among children and adults, it is well recognized that in both populations, food and aeroallergen sensitization and allergy have been associated with the pathogenesis of the disease. A history of atopy is documented in 50–60 % of all patients, and 40–93 % of pediatric subjects have been previously diagnosed with another allergic disease [9, 32, 33]. The immune process implicated in OE is most likely a combination of immunoglobulin E (IgE)- and non IgE-mediated reaction to allergens. Peripheral eosinophilia occurs in 50 % of the cases and increased levels of IgE are documented in three fourth of the patients [6]. However, remission of the disease cannot always be easily achieved by eliminating specific food for which patients test positive with skin prick tests (SPTs) and food specific-IgE antibodies. On the contrary, patients who exhibited negative allergy tests have shown a good response to elimination diets [34, 35]. The existing data point only an association between EoE and allergy, and the first is not definitely considered as an allergic condition .

Esophageal eosinophilia is not pathognomonic for the disease, but a nonspecific finding that reflects a state of injury [36]. Eosinophils are multifunctional cells and secrete a variety of cytokines, chemokines, inflammatory mediators, neuromediators, and cytotoxic granule proteins when activated [37]. These cells tend to accumulate in the apical strata, but can be also distributed diffusely throughout the mucosal membrane in EoE [38]. Microabscesses formed by coalesced eosinophils, the extracellular deposition of eosinophilic proteins, and the deposition of major basic proteins (MBP) are specific findings of the disease, not commonly seen in gastroesophageal reflux [39, 40] . The main question to be answered is which is the driving force for the presence of eosinophils in the esophageal squamous epithelium.

Emerging evidence suggests that a Th2-type immune response with systemic and local Th2-cytokine overproduction plays a key role in the pathogenesis and onset of the disease [41]. Studies in murine models have demonstrated that eosinophilic and collagen deposition is interleukin (IL) 5 dependent [42–44]. IL-5, IL-4, and IL-13 act as chemoattractants for eosinophils that leave the vascular space by diapedesis and enter the esophageal mucosa. Subsequently, the expression of the beta-integrin very late antigen (VLA)-4 on the eosinophilic surface and its counter ligand, the vascular endothelial adhesion molecule, VCAM-1 on endothelia is induced. Further studies in murine models and ex vivo analysis of human esophageal cells support the key role for IL-15 in the generation and the perpetuation of esophageal inflammation . IL-15 is a cytokine with the ability to potentiate activated T cell responses. Following IL-15 stimulation, an increase in eotaxins has been identified [45, 46] .

The eotaxin proteins (eotaxin-1, -2, and -3), also known as chemokine cysteine–cysteine motif ligand (CCL) 11, CCL24, and CCL26 respectively, are highly potent eosinophilic chemoattractants. Many studies have investigated the role of eotaxin-3 in EoE . Genome-wide microarray analysis on esophageal biopsies from pediatric subjects revealed an increase in eotaxin-3 (messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and protein), which is mainly produced by esophageal epithelial cells, and correlated with the eosinophilic counts. A single-nucleotide polymorphism in the untranslated region of the eotaxin-3 has been associated with increased disease susceptibility [47]. This conserved gene profile, with the increased expression of eotaxin-3, distinguishes between EoE and gastroesophageal reflux disease [48]. Furthermore, the expression of cysteine–cysteine motif containing chemokine receptor 3 (CCR3) that receives signals from eotaxins and CCL5 was found increased and correlated positively with the number of esophageal eosinophilic and biopsy eotaxin message [49]. On the contrary, in murine models, mice deficient in the chemokine receptor CCR3 were protected from EoE [47, 50].

A better understanding of the immunomicroenvironment of the disease has revealed the implication of mast cells. In normal states, mast cells reside at the basement membrane and in the lamina propria of the esophageal mucosa [51]. Even though the exact mechanism of the underlying esophageal mastocytosis in EoE has not yet been clarified, immunohistochemical staining has shown the increased number of intraepithelial mast cells compared to healthy controls and gastroesophageal disease [38, 52–54]. The tryptase-positive mast cell quantification may have diagnostic utility in EoE, particularly in differentiating the disease from gastroesophageal reflux [55] . Taken into consideration that carboxypeptidase A3 has the strongest relation to mast cell number and degranulation, the upregulation of carboxypeptidase A3 gene, specifically seen in EoE, highlights the importance of mast cells in the pathogenesis of the disease [47, 54]. Furthermore, IL-9 is known to promote esophageal mastocytosis and the expression of the IL-9 transcript is increased in the esophagus of patients with EoE [45, 56]. Following treatment with anti-IL-5, the esophageal epithelium of pediatric patients had significantly fewer mast cells, IL-9, and mast cell-eosinophilic couplet [57].

Both eosinophils and mast cells with their secretory products contribute to tissue remodeling and fibrosis in EoE. A complex interplay between eosinophils , mast cells, and fibroblasts has been documented. Tumor growth factor (TGF)-β1 is produced mainly by monocytes and macrophages, and also by eosinophils and mast cells. This pro-fibrotic molecule increases smooth muscle cell hyperplasia, is a potent activator of fibroblasts, and is a strong inducer of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), the process where epithelial cells assume morphological and phenotypical properties of fibroblasts [58]. Evidence of EMT was seen in esophageal mucosal biopsies from patients with EoE [59]. Increased vimentin expression in the esophageal epithelial cells combined with decreased expression of E-cadherin also indicates the possible presence of EMT in EoE tissues [60].

In a pediatric study, an increased expression of TGF-β1 and its signaling molecule phosphorylated SMAD2/3 (phosphor-SMAD2/3) was documented. The esophageal biopsies also demonstrated remodeling of the esophageal mucosa, especially the lamina propria, as well as increased vascular density and increased expression of the vascular endothelial adhesion molecule, VCAM-1. Increased level of esophageal fibrosis was documented in children with EoE . TGF-β1, VCAM-1, SMAD2/3 seem to contribute to the loss of elasticity of the esophageal wall and the formation of strictures [61, 62]. Basal cell hyperplasia correlates with the intraepithelial eosinophils and the number of mast cells [47]. Furthermore, MBP, released by eosinophils, lead to increased gene expression of fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-9, a cytokine implicated in the proliferate response to eosinophilic inflammation in esophagitis [63]. The role of periostin, a cell adhesion protein with the ability to bind to integrins in the cell membrane and trigger cell proliferation, migration, adhesion, and differentiation, has also been studied. In gene arrays, periostin is highly overexpressed in the esophagus of patients with EoE, it is second in upregulation magnitude only to eotaxin-3 gene and it correlates with the eosinophilic number [47, 64]. Interestingly, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-a is also highly expressed by epithelial cells in EoE, but it remains to be clarified whether it exerts direct pro-fibrotic effect [65].

Genome-wide association studies that investigate the association between common genetic variants across the genome and the disease have identified various single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in a discrete region on the long arm of chromosome five associated with the thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) in patients with EoE. Esophageal biopsies of pediatric patients showed TSLP overexpression compared to unaffected controls and TSLP expression levels correlated significantly with the disease-related rs3806932 SNP [66, 67].

In conclusion, despite the advances in our understanding, the pathogenesis of EoE is yet not fully understood. An interplay between predisposed genetic background with environmental factors seems crucial for the onset of the disease. There is strong evidence that cell types other than eosinophils are also implicated. However, the current challenge is to elucidate the complex cellular and molecular mechanisms of the disease .

Clinical Presentation

EoE can affect any age, but the symptomatology varies according to age . Substantial differences have been described between pediatric and adult patients (Table 9.2); however, it remains unclear whether this variation could be attributed to the ability to enunciate discomfort or to the different stages of the disease [68].

Table 9.2

Clinical manifestations of eosinophilic esophagitis in children, adolescents, and adult patients

Children | Adolescents and adults |

|---|---|

Chest pain or heartburn | Dysphagia |

Abdominal pain | Retrosternal pain |

Coughing | Food impaction |

Dysphagia | – |

Food refusal | – |

Decreased appetite | – |

Choking/gagging/vomiting | – |

Nausea | – |

Regurgitation | – |

Throat pain | – |

Sleeping difficulties | – |

A broad range of symptoms, affecting the upper gastrointestinal tract and the respiratory system, has been reported in the pediatric population. Symptoms can attenuate or spontaneously fluctuate, even when histology reveals persistent esophageal eosinophilic infiltrates [69]. In general, the most common symptoms can be divided to GERD-like symptoms and dysphagia , possibly representing two discrete disease phenotypes [70]. In infants and toddlers, the disease presents with nonspecific symptoms, like feeding difficulties, regurgitation , vomiting, and feed refusal, which can result in poor weight gain.

Older children and adolescents complain of upper abdominal and retrosternal pain, heartburn, dysphagia, and food impaction . Furthermore, pediatric patients can experience choking on liquids or solids, the inability to tolerate feeds beyond certain tastes or textures, avoidance of specific solid foods, such as bread, rice, meat, and the need to drink water to assist swallowing during meals as an adaptive behavior to esophageal dysfunction [20, 71]. Acute symptoms are due to intermittent esophageal spasm, most likely related to smooth muscle contraction, whereas the chronicity of dysphagia denotes long-standing esophageal remodeling [72, 73]. Interestingly, the seasonality of symptoms points the implication of aeroallergens [74] .

Association with Other Diseases

The relationship between EoE and gastroesophageal reflux disease is complex and the role of acid reflux in the EoE is a matter of debate [68]. Impedance and pH studies are helpful in distinguishing the two entities; however, conflicting data exist about the presence of acid and nonacid reflux in children with EoE [75, 76]. It is postulated that the erosions and ulceration seen in gastroesophageal reflux disease can result in the impairment of the mucosal barrier function and increase the risk for food sensitization. Furthermore, the ineffective esophageal peristalsis in EoE can lead to an impairment of the clearance of the esophagus after gastroesophageal reflux episodes [77, 78]. Emerging evidence shows that the two distinct entities can possibly coexist and exacerbate each other .

The recent identification of PPI-REE that was first described in a series of pediatric patients complicated further the diagnostic algorithms of esophageal eosinophilia [79]. PPI-REE accounts for at least one third of children and adults with esophageal eosinophilia [80–82], but it has not been yet elucidated if this is a new separate entity, a subtype of gastroesophageal reflux disease or a phenotype of EoE. Given the current state of knowledge, the clinical, endoscopic, and histological features cannot differentiate it from EoE, and there is no predictor to show which patient will respond to the PPI trial [83]. According to the most recent guidelines, in order to identify children with PPI-REE and to avoid unnecessary eliminations diets and drug treatment, an 8-week trial of PPIs is recommended, before the diagnosis of EoE is established [80] .

Celiac disease and EoE both affect the upper gastrointestinal tract, and they are two clinically, anatomically, and histologically distinct entities. However, recently a clinical association between these two disorders has been proposed. A higher than expected prevalence of EoE in pediatric patients with coeliac disease has been documented, and the estimated risk of each condition is increased 50–75-fold in those pediatric patients diagnosed with the alternative condition. This phenomenon is shown to be limited only to the pediatric population [84–90]. The lack of a genetic connection between EoE and coeliac disease necessitates further prospective studies to shed light to this association and to clarify the underlying mechanisms that justify the coexistence.

The implication of TGF-β1 in the pathogenesis of EoE led to the hypothesis that the disease could be also associated to connective tissue disorders (CTDs) that are known to be caused by genetic variants in TGF-β binding proteins and TGF-β receptors, like Marfan syndrome and Loeys–Dietz syndrome, respectively [91, 92]. In addition, patients diagnosed with the above disorder can exhibit gastrointestinal symptoms, including dysphagia , which is a typical presenting symptom of EoE [93–95]. Taken this into consideration, a new syndrome has been described (EoE-CTD), involving EoE in association with inherited CTDs that represents a new class of this gastrointestinal disorder. There is evidence showing that the dysregulation of collagen transcription in patients with EoE-CTD is distinct from that seen in typical patients with EoE or healthy subjects, and that these patients might be at greater risk for more diffuse eosinophilic extraesophageal gastrointestinal disease than their peers with EoE without evidence of CTDs [96, 97] .

Diagnosis and Assessment

The presence of eosinophils in the esophageal epithelium should be reported as esophageal eosinophilia . Consensus recommendations have proposed a threshold of 15 eosinophils or more per HPF in at least one endoscopic esophageal mucosal biopsy sample taken at upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Other microscopic features which often accompany EoE include eosinophilic microabscesses, superficial layering, extracellular eosinophilic granules, the basal cell hyperplasia, papillary elongation, lamina propria fibrosis, and dilatation of intercellular spaces (Table 9.3) [6]. It is important to note that none of these individual histological features are specific, and they should not be used in isolation to differentiate EoE from other conditions associated with esophageal eosinophilia (Table 9.1) . Inclusion in the routine staining panel of stains such as diastase-periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) ensures that fungal organisms are not easily overlooked. Even if eosinophilic esophagits is suspected clinically, sampling should include gastric and duodenal mucosa, as presence or absence of gastroduodenal changes may be helpful in the differentiating EoE from other conditions .

Table 9.3

Diagnostic criteria, macroscopic, and histological findings of eosinophilic esophagitis

Diagnosis | – |

|---|---|

Macroscopic findings | Thickened/pale mucosa Linear furrows Trachealization (esophageal rings) Mucosal friability White exudates Luminal strictures |

Histological characteristics | Esophageal eosinophilia: After antireflux therapy High eosinophilic count in the most affected area (> 15 eosinophils/HPF as proposed by consensus panel [6]) Eosinophilia affecting lower, mid, and upper esophageal samples Other associated features: Eosinophilic microabcesses Superficial layering Extracellular eosinophilic granules Basal cell hyperplasia Papillary elongation Lamina propria fibrosis Dilated intracellular spaces No parasites or fungi present |

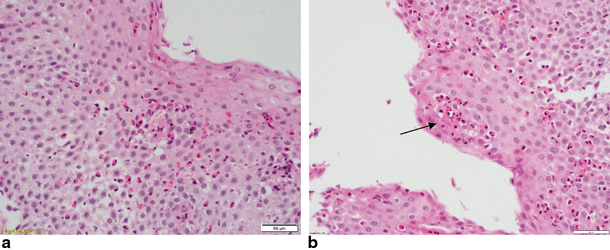

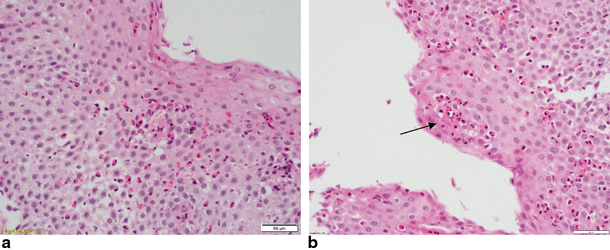

In the particular context of differentiating EoE from gastroesophageal reflux, the presence of esophageal eosinophilia in biopsy samples from the mid and upper esophagus is a very useful feature in support of EoE as these sites are rarely affected by reflux. Multiple biopsy samples should always be taken as the eosinophilic infiltrate can be patchy in distribution. In terms of diagnostic sensitivity, this has been reported to range from 55 % when one specimen is examined to 100 % when five specimens are examined [98]. See (Fig. 9.1). It has been proposed that diagnosis can be achieved in 97 % of the patients by at least three biopsies form different parts of the esophagus [99]. It is therefore recommended two to four biopsies to be taken from the proximal and distal esophagus regardless its appearance [6]. EoE cannot be excluded even if esophagus has a normal appearance at endoscopy. However, the characteristic macroscopic findings include thickened, pale mucosa with linear furrows, trachealization (fixed esophageal rings), mucosal friability, white exudates, and less frequently luminal strictures (Table 9.3) [100] .

Fig. 9.1

a Twelve-year-old child. Esophageal squamous epithelium from upper esophagus infiltrated by a high number of eosinophils, well in excess of 15 per HPF. H&E 400 × magnification (40 × objective). b Twelve-year-old child. Same child as picture (a). Esophageal sample from mid esophagus. The heavy eosinophilic infiltrate includes a microabscess (arrow)

The role of repeat endoscopy and biopsies in order to reassess the disease and the effect of the treatment has not yet been validated. Some centers suggest regular upper endoscopy to ensure maintenance of histological remission, but currently the long-term follow-up management for asymptomatic patients is poorly defined [78]. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast radiography is helpful in identifying esophageal strictures or long-segment narrowing, although the findings are not always confirmed at endoscopy, suggesting transient contractions [101, 102]. Deeper esophageal strictures have been also assessed with the use of endoscopic ultrasound, and data from a pediatric series suggest a significant thickening of the esophageal wall with the involvement of the submucosa and the muscularis propria apart from the mucosa [103] .

The most common manometric disorder in EoE is the ineffective peristalsis of the esophagus . High-resolution manometry can reveal pan-esophageal pressurization, the uniform esophageal pressurization form the upper esophageal sphincter to the esophagogastric junction with pressures over 30 mmHg [77]. Pediatric patients have shown significantly more ineffective esophageal peristalsis during fasting and meals than those with gastroesophageal reflux disease and controls [104]. A novel imaging probe, the endolumenal functional lumen imaging probe (endoFLIP), used in adult patients determined that patients with EoE also exhibit significantly reduced distensibility compared to normal controls .

An ideal biomarker for EoE should correlate with disease activity, have high sensitivity and specificity, reflect changes with therapy, be reproducible, noninvasive and cost-effective [105, 106]. Currently, there is no available biomarker to confirm or monitor the disease. Peripheral eosinophilia is not always present, and even when identified, it can be indicative of other diseases. However, the combination of peripheral eosinophilia with elevated serum levels of eotaxin-3 (CCL26) and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin significantly correlated with esophageal eosinophilic density [107]. Furthermore, the Th2 induction implicated in EoE results in cytokine pattern variation in eosinophilic and normal subjects. A cytokine panel scoring system for predicting the diagnosis of EoE has been proposed and identified that IL-13 as one of the eight cytokines whose blood levels retrospectively distinguished patients from healthy controls with 100 % specificity and sensitivity. Serum and tissue expression levels of IL-13 is one of the most promising candidate biomarkers for the disease [45, 108].

Mast cell density, the extracellular MBP content, and the presence of fibrosis may serve as potential biomarkers in establishing the diagnosis of EoE [109]. Recently, the use of a minimally invasive test, the esophageal string test (EST), in pediatric patients was shown to have the potential to significantly improve the evaluation and treatment of the disease by measuring the eosinophil-derived proteins in luminal secretions which reflect the state of mucosal inflammation [110] .

Treatment

In order to avoid unnecessary elimination diets and drug therapy and to differentiate PPI-REE and EoE, the diagnosis of the latter is established when esophageal eosinophilia does not respond to an 8-week course of PPIs at repeat endoscopy . According to the most recent guidelines, the end points of the treatment should include the combination of clinical remission with histological resolution of the esophageal eosinophilic inflammation [3, 78]. Two different treatment approaches have been proven to be effective in the management of the disease, the elimination diets, and the pharmacological therapy. (Table 9.4)

Table 9.4

Management of eosinophilic esophagitis

Dietary approach | Amino-acid-based formula Skin test-directed elimination diet Empiric elimination diet |

Pharmacological approach | Topical steroids (fluticasone proprionate, oral viscous budesonide) Systemic steroids (oral, IV) |

Esophageal dilatation | Combined with pharmacological therapy |

Dietary Management of EoE

The success of elimination diets in EoE provides strong evidence for the implication of food sensitization as the cause of esophageal inflammation in many cases [74]. The observation that some patients exhibit allergen sensitivity while others do not, points the possibility that the disease may exhibit different phenotypes [111]. Atopy patch test (APT), SPT, and serum IgE tests may be adjunctive in identifying a causative food in EoE, and, for that reason, gastroenterologists should consider consultation with an allergist. However, a food trigger can only be identified when the elimination of the specific food results in disease remission, followed by relapse upon reintroduction [6] .

The dietary management of EoE includes the diet based on amino-acid formula, the skin test-directed elimination diet, and the empiric exclusion diet, with the elimination of six foods. The decision as to which of these three dietary approaches to be suggested should be individualized according to the patient’s specific needs and family circumstances . Important foods that are excluded from a child’s diet should be substituted appropriately and the input of an experienced dietitian in pediatric nutrition is crucial to ensure a balanced nutritional plan, to minimize non-adherence, and to avoid cross-reactive antigens [78, 112] .

The efficacy of an amino-acid-based formula for the treatment of EoE in children was first described in 1995 [113]. Since then, several studies have shown the successful use of the elemental formula that seems to achieve clinical and histological remission in less time compared to the other two elimination diets [24, 114–116]. A 4-week trial of amino-acid-based formula is recommended in patients with multiple food allergies, failure to thrive, or those unable to respond or to follow a highly restricted diet [78]. However, the clinical use of this dietary approach is limited by the acceptability that often requires tube feeding (nasogastric or gastrostomy) and the significant cost. Generally, it is better accepted and tolerated in infants [114] .

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree