ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a critical tool in cancer staging and is superior to computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET), in locoregional esophageal cancer staging.

EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is the most sensitive method for diagnosing pancreatic cancer; overall accuracy of EUS is similar to CT for assessing vascular invasion.

EUS helps evaluate subepithelial lesions, although the yield of EUS-FNA is lower for subepithelial than for extraluminal lesions.

EUS is as an important tool in diagnosing chronic pancreatitis.

Diagnostic yield for EUS is similar to magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in detecting choledocholithiasis with the choice of modality guided by local availability.

EUS is the premier tool for staging gastrointestinal cancers and has revolutionized the role of gastrointestinal endoscopy in diagnostic imaging inside and outside the gastrointestinal tract. EUS merges endoscopy, which is limited to visualizing the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract, with ultrasonography, which allows imaging of the layers of the gastrointestinal wall and surrounding structures. Tissue diagnosis can be obtained with EUS-FNA, which uses a catheter with a retractable needle that can be advanced into visualized tissue. Exciting advances in the therapeutic application of EUS have begun, including the well-established endoscopic pseudocyst drainage and more recent biliary and pancreatic duct access techniques as well as possibilities of EUS-guided fine-needle injection (EUS-FNI) therapy.

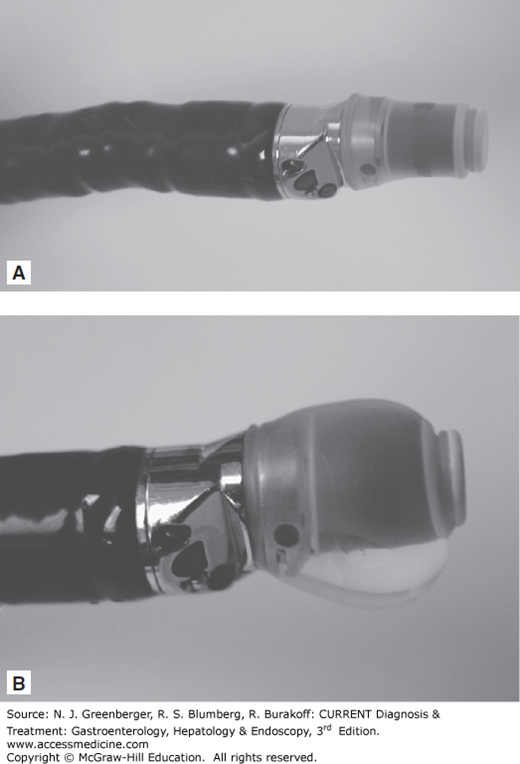

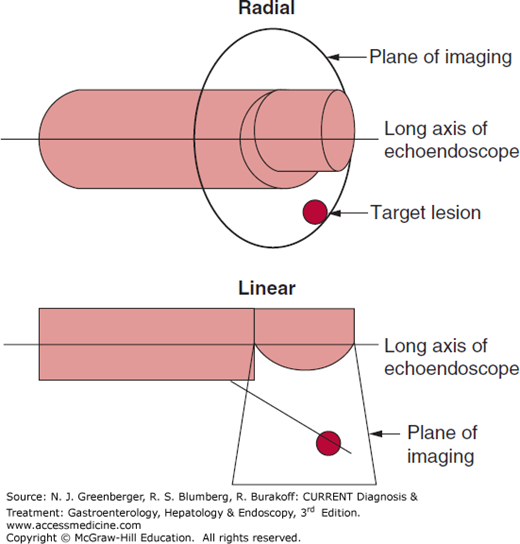

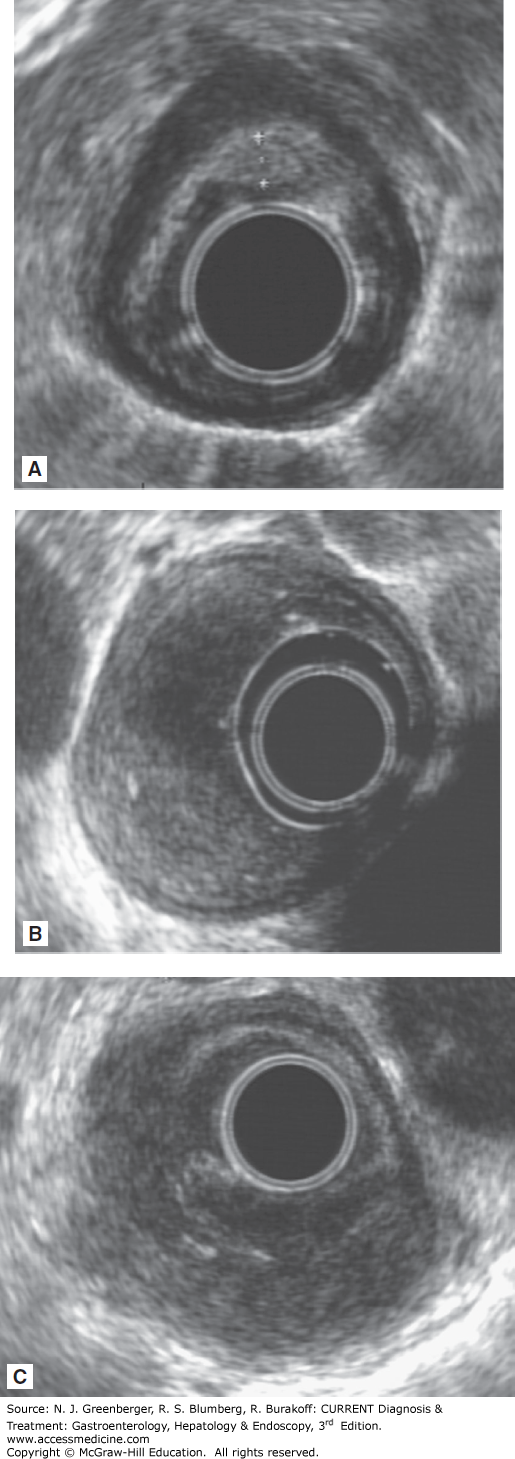

Radial scanning echoendoscopes were the first instruments used with the advent of EUS in the 1980s (Figure 37–1). The ultrasound transducer is mounted on the tip of the endoscope and rotates 360 degrees to provide cross-sectional images perpendicular to the long axis of the endoscope (Figure 37–2). The endoscopic viewing optic is mounted proximal to the ultrasound transducer and provides an oblique view of the lumen. A new forward-viewing echoendoscope has been developed. To overcome the problem of ultrasound waves traveling through an air-filled lumen, a balloon that can be filled with water surrounds the ultrasound transducer. Various ultrasonic frequencies between 5 and 20 MHz are used.

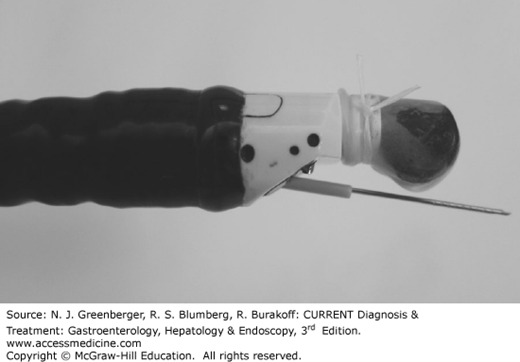

Linear array echoendoscopes provide ultrasound images along the long axis of the endoscope usually in a 120- to 180-degree arc (Figures 37–2 and 37–3). This is critical to allow simultaneous imaging of the needle and target lesion during EUS-FNA. A variety of needles, including 19-, 22-, and 25-gauge, can be passed through the endoscopic working channel.

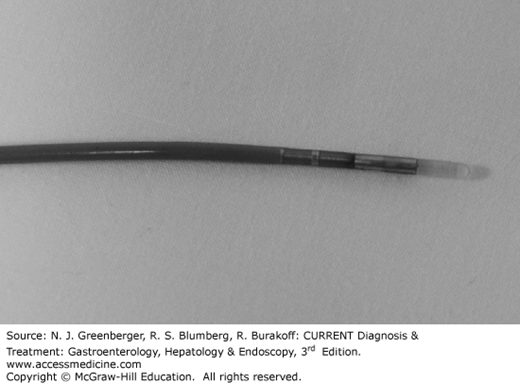

In high-frequency ultrasound probe sonography, a catheter with a tiny mechanically rotating ultrasound transducer at the tip is inserted through the endoscopic working channel (Figure 37–4). The probe images with frequencies between 12 and 30 MHz, and higher resolution allows for more detailed imaging but with decreased depth of penetration. Wire-guided probes can be introduced into the biliary and pancreatic ducts to perform intraductal ultrasound.

Typically a standard upper endoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy for a rectal EUS is performed before the EUS to identify the area of interest and to ensure the echoendoscope can be passed safely in the gastrointestinal tract. The echoendoscope is passed in a “blind” manner similar to the duodenoscope. Once the echoendoscope has been advanced to the area to be imaged, a water interface is established between the ultrasound transducer and the gastrointestinal wall. This can be done by inflating the balloon on the tip of the transducer or by filling the gastrointestinal lumen with water, or both. Once a sufficient water interface has been established, EUS images should be obtained perpendicular to the lesion of interest as oblique images commonly distort the gastrointestinal wall and lead to false interpretations.

EUS-FNA is performed with the linear echoendoscope. The needle is advanced under endosonographic guidance into the lesion of interest, the stylet may be withdrawn, and suction may be applied using a 10- to 25-cc syringe while advancing the needle back and forth within the lesion.

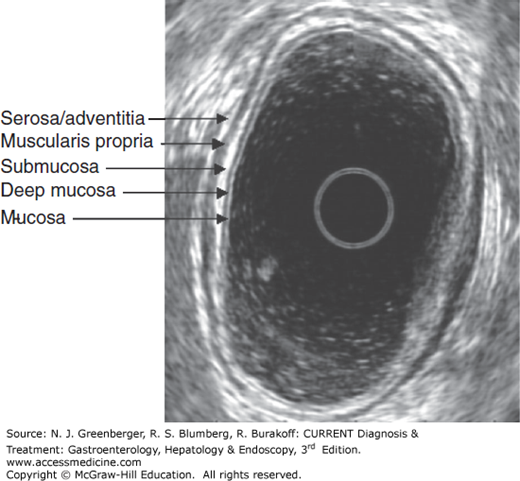

EUS imaging of the gastrointestinal wall layer typically reveals five layers alternating in bright and dark bands (Figure 37–5). The first bright or hyperechoic layer closest to the probe represents the superficial mucosa; the second dark or hypoechoic layer corresponds to the deep mucosa or muscularis mucosa; the third hyperechoic layer is the submucosa; the fourth hypoechoic layer is the muscularis propria; and the fifth hyperechoic layer represents the serosa or adventitia. The normal thickness of the gastrointestinal wall varies from 2 to 4 mm.

CANCER STAGING

Most cancers are staged according to the TNM system of the American Joint Commission on Cancer. Depth or extent of tumor invasion (T), presence or absence of locoregional lymph nodes (N), and presence or absence of distant metastases (M) are captured by the TNM system. The stages of tumor invasion are defined as Tis, limited to mucosa, lamina propria intact; T1, invades lamina propria or submucosa; T2, invades muscularis propria; T3, invades adventitia or serosa; and T4, invades surrounding structures.

As with many cancers, the prognosis of esophageal cancer correlates with stage at diagnosis. Although the optimal management of patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer remains controversial, preoperative chemoradiation likely improves survival compared with surgery alone. In addition, endoscopic resection provides curative therapy for select T1 tumors. Thus, accurate staging is important to select the appropriate patients for optimal treatment.

The TNM staging includes tumors at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction and the proximal 5 cm of the stomach extending into the GE junction or esophagus. Multiple studies have confirmed the superiority of EUS over CT in T and N staging of esophageal cancer (Figure 37–6 and Table 37–1). Both CT and fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) identify more distant metastases than EUS, and FDG-PET appears superior to CT.

With the high-frequency ultrasound probes, T1 stage can be subdivided into T1m (tumor confined to mucosa) and T1sm (tumor invading submucosa) more accurately than using a conventional echoendoscope. About 8–50% of T1sm tumors have local lymph node metastases. Patients with stage T1sm cancer have a lower 5-year overall survival rate of 58% compared with 91% for T1m; therefore, local endoscopic therapy should not be performed for T1sm lesions.

| Modality | T Stage | N Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Esophageal Cancer | ||

| CT | 50% | 50–60% |

| PET | — | 60% |

| EUS | 61–90% | 75% |

| EUS-FNA | — | 87% |

| Gastric Cancer | ||

| Multidetector-row CT | 77–89% | 50–75% |

| MRI | 71–83% | 52% |

| EUS | 65–92% | 50–87% |

| Rectal Cancer | ||

| CT | 65–75% | 54–70% |

| Endorectal coil MRI | 75–85% | 65–76% |

| EUS | 80–95% | 70–75% |

For each T stage, positive nodes increase the overall tumor stage and predict a worse prognosis. EUS characteristics suggestive of a malignant lymph node include size greater than 1 cm, round, well defined, and hypoechoic. Presence of all four features predicts malignancy in 80–100% of cases, but only 20–40% of all malignant lymph nodes have all four findings. FNA of lymph nodes improves accuracy of nodal staging compared with EUS alone. If FNA is not possible, the number of lymph nodes correlates with 5-year survival, and the staging system incorporates number of metastatic regional lymph nodes in nodal staging. In addition, celiac axis lymph nodes as well as lymph nodes in the chest and around the esophagus are all considered regional nodes.

Restaging of esophageal cancer following chemoradiation with EUS is significantly less accurate than pretreatment staging. Accuracy of T staging is about 29–60%, and the majority of tumors are overstaged presumably due to peritumor inflammation and fibrosis being mistaken for tumor. Reduction in the cross-sectional area or thickness of the tumor by more than 50% has been associated with response to treatment and possibly improved survival.

The clinical impact of EUS on management of esophageal cancer has been demonstrated in several studies. Treatment strategy was changed in about 75% of patients following EUS-FNA, and performance of EUS was associated with increased recurrence-free and overall survival. This was attributed to greater use of chemoradiation following more accurate preoperative staging with EUS.

[PubMed: [PMID: 16006804]]

[PubMed: [PMID: 17321235]]

Similar to esophageal cancer, perioperative chemotherapy may improve survival in specific patients with operable gastric adenocarcinoma, while endoscopic resection is also indicated for early-stage gastric cancers. Therefore, accurate pretreatment staging is important in determining appropriate management. Accuracy of EUS appears similar to multidetector-row CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for T and N staging of gastric cancer. EUS-FNA of lymph nodes likely increases accuracy for N staging. As with esophageal cancer, EUS can identify superficial mucosal tumors, which may be amenable to endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection. Limitations in accuracy of EUS staging in gastric cancer include early cancers, large or ulcerated lesions, and lesions at the cardia or incisura.

EUS-staging of gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas is 95% accurate for T staging and seems to predict response to Helicobacter pylori treatment. Complete remission occurs in 78% of patients with T1m disease compared with 12.5% of patients with T1sm tumor. Therefore, EUS may allow early selection of patients with higher T stage disease for consideration of other treatments.

[PubMed: [PMID: 12269963]]

Preoperative chemoradiation followed by radical resection for rectal cancers that have extended into the perirectal fat or have local lymph nodes (T3/T4, N1, or both) decreases local recurrence by about half to less than 10% and possibly improves survival. There are limited data on the benefits of adjuvant chemoradiation in patients with unfavorable T1 or T2 tumors. Tumor size greater than 3 cm, poorly differentiated histology, and lymphovascular invasion are associated with increased risk of lymph node metastases. Local recurrence can be as high as 11–29% for T1 tumors and 25–62% for T2 tumors, which most likely reflects lymph node involvement occurring in 0–12% of T1 and 12–28% of T2 tumors. Therefore, local excision, which does not remove the mesorectum containing lymph nodes, rather than radical resection should be performed in only select patients with favorable T1 tumors.

Accurate staging of rectal cancer is thus critical for correct patient selection for the appropriate preoperative and operative treatment. EUS remains superior to CT for both T and N staging; however, the accuracy of EUS appears comparable to endorectal coil MRI for both T and N staging. The modest accuracy of EUS for staging rectal cancer is attributed to several factors, including inflammation surrounding the tumor leading to overstaging; operator experience; and level of tumor in the rectum, with distal lesions being staged less accurately.

Similar to esophageal cancer, EUS-FNA of regional lymph nodes in rectal cancer appears to improve accuracy of N staging. EUS imaging alone found that presence of malignant EUS features (size ≥10 mm, hypoechoic, round, smooth border) was not predictive of malignant lymph nodes unless all four criteria were present. In addition preoperative EUS-FNA of extramesenteric lymph node metastases upstages 7% of rectal cancers. Therefore, EUS-FNA of lymph nodes in rectal cancer is recommended to determine nodal status. Prophylactic antibiotics are not necessary for transrectal EUS-FNA procedures of solid lesions due to low risk for infectious complications.

EUS-FNA may offer a powerful method to survey for local recurrence of rectal cancer, which often occurs extraluminally following surgical resection. Standard endoscopy is inadequate for detecting these recurrences, and CT scan is limited due to artifacts from surgical metal clips and the inability to differentiate between postoperative changes and recurrence. Sensitivity of EUS for detecting recurrence is 91–100% compared with 82–85% for CT scan, with limited specificity for EUS of 57% that improves to 93% with EUS-FNA. There is no standard recommendation for surveillance with EUS following surgical resection; however, the patients who may benefit most include those with more advanced stage tumors at diagnosis. The greatest risk of recurrence occurs in the first 2 years following surgery; therefore, EUS may be performed every 6 months during this time.

The role of EUS in pancreatic cancer includes diagnosis (Figure 37–7) and staging. Tissue diagnosis is important to confirm malignancy and rule out metastatic lesions to the pancreas, which comprised 11% of masses referred for EUS-FNA in one study. EUS-FNA is the most accurate diagnostic modality, with 80–95% sensitivity and near 100% specificity compared with CT- or ultrasound-guided FNA, which have sensitivity ranging from 62% to 81%. Diagnostic sensitivity diminishes to 73% in the setting of chronic pancreatitis. Presence of an onsite cytopathologist increases diagnostic accuracy while reducing procedure time, number of needles used, and overall procedure cost. EUS-FNA is favored because of its accurate detection of small lesions less than 1.5 cm, and because the needle tract along which seeding can theoretically occur is resected for lesions in the pancreatic head. Tumor spread along the needle tract was suspected in a case report of a patient who developed recurrent cancer within the gastric wall 16 months after complete resection of a T1N0M0 pancreatic tumor located in the pancreatic tail. Therefore, for potentially resectable tumors located in the pancreatic body or tail, the options of proceeding directly to surgery without a tissue diagnosis versus EUS-FNA should be considered.

The best outcome in pancreatic cancer occurs in patients without nodal, vascular, or systemic metastases (5-year survival up to 25%). More accurate patient selection could reduce unnecessary surgeries in patients with unresectable tumors. A recent review of studies comparing EUS and CT for preoperative staging of pancreatic cancer concluded that it is unclear which modality is superior for both tumor and nodal staging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree