INTRODUCTION

Since the introduction of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatoscopy (ERCP) in 1968 and endoscopic sphincterotomy in 1974, the management of various biliary and pancreatic illnesses has evolved from surgical to endoscopic methods with substantial improvements in patient outcomes. Additionally, development of custom accessories has improved procedural efficiency and success rates; these include balloons and baskets for stone extraction, lithotripsy devices, stents, drains, and duodenoscope-assisted cholangiopancreatoscopy. In expert centers success rates for many therapeutic endoscopic interventions exceed 90%.

Several acute biliary and pancreatic conditions are amenable to endoscopic diagnosis and therapy. ERCP has been shown to have better outcomes than surgery when dealing with most ductal obstructions and leaks. Additionally, ERCP may have a limited role in the diagnosis of bleeding conditions and the treatment of associated complications. This chapter details endoscopic treatment options for these conditions.

ACUTE CHOLANGITIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of acute biliary obstruction with cholangitis relies on clinical findings, blood counts, blood chemistries, biochemical profile, and imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

Endoscopic biliary drainage is the standard of care, with emergent drainage for patients not responding to antibiotics and supportive measures or showing signs of clinical deterioration (ie, hypotension, altered mental states, and signs of continuing infection such as persistent fever).

Acute cholangitis is characterized by biliary stasis and infection of the bile ducts. In 1877, Charcot defined the clinical triad of fever, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice that is present in up to 70% of patients with acute cholangitis. The spectrum of clinical presentation ranges from mild pain and low-grade fever, to a fulminate course with hypotensive sepsis. In 1959, the Charcot triad was modified to include hypotension and mental status changes, subsequently known as the Reynolds pentad. Clinical presentation is, however, not useful in differentiating between suppurative and nonsuppurative cholangitis, which can only be determined at the time of therapy. In the latter form, bacteria are still present in bile, but without the formation of pus. Suppurative cholangitis has a more acute course and is less likely to respond to antibiotics; however, either form is potentially life threatening, and when acute cholangitis is suspected urgent diagnosis and treatment are critical.

Bile duct obstruction and infection are requisite for the development of cholangitis. Over 90% of cases are attributed to common bile duct stones. Other causes of obstruction include iatrogenic biliary instrumentation and endoprostheses. Less common causes include malignant biliary obstruction, benign bile duct strictures, ampullary adenomas, periductal adenopathy, choledochal cysts, parasites, and blood clots.

Following bile duct obstruction and biliary stasis, infection may occur either by direct ascent from the bowel, or via the lymphatics or portal vein. The latter assumes translocation of bacteria from the bowel into the portal circulation and subsequent clearance of bacteria by the reticuloendothelial system with excretion into bile. Although the origin of infecting organisms is questionable, the most common organisms are enteric and often polymicrobial. Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Proteus are most common, while enterococcus and anaerobes are less frequent. Positive bile cultures are seen in approximately one-third of patients with bacteremia.

Initial studies include blood cultures, a complete blood count, and a full biochemical profile. Several noninvasive imaging studies are available to diagnose biliary obstruction. Abdominal ultrasound is sensitive for intrahepatic biliary dilation; however, it is poor at identifying choledocholithiasis, with a sensitivity of less than 30%. Additionally, up to one-third of patients with choledocholithiasis do not have evidence of biliary dilation, and cholangitis can occur before the bile duct becomes dilated. Nuclear hepatobiliary imaging can detect biliary obstruction earlier than ultrasound, with higher sensitivity. However, MRI with MRCP is most accurate, with a sensitivity of 97%. ERCP is no longer viewed as an initial diagnostic option and is reserved for therapy.

Supportive care for sepsis with volume resuscitation and broad-spectrum antibiotics, including gram-negative coverage, should be promptly instituted. Additionally, anaerobic and pseudomonal coverage should be considered if there is a history of prior instrumentation. Up to 85% of patients will respond to these conservative measures allowing for semi-elective biliary drainage within 48 hours. Emergent drainage is indicated in those patients who do not respond to conservative measures or when clinical deterioration occurs, particularly with the development of hypotension or alteration of mental status.

Endoscopic biliary drainage is the standard of care for most causes of cholangitis. Definitive therapy typically involves endoscopic sphincterotomy with removal of stones or other obstructions. This has proven to be safer than surgical options. Complete clearance of gallstones is possible in up to 90% of cases on the initial procedure, with morbidity and mortality rates of 6% and near 0%, respectively.

It is important to avoid excess contrast injection, since this may precipitate cholangiovenous reflux and sepsis. Bile should initially be aspirated to decompress the collecting system, with samples sent for culture which may aid in tailoring of antibiotics for a specific pathogen. The amount of contrast injected should be half that of the bile removed to reduce raising the pressure in the biliary system which may increase the risk of liver abscess and/or hematologic seeding.

If the patient is particularly ill or on anticoagulation, a two-step approach may be preferred, consisting of ERCP with stent placement alone followed by definitive endoscopic sphincterotomy and stone removal when the patient is more appropriately prepared. Additionally, when stones are too large to remove, stents may be placed as a temporizing measure to ensure adequate drainage.

Mechanical or electrohydraulic lithotripsy may be necessary for the complete removal of large common duct stones (>2 cm). This should not be attempted during the initial treatment of acute cholangitis.

When endoscopic drainage is not possible, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) with drainage is indicated. The degree of urgency similarly depends on the clinical situation; however, emergent drainage should be performed if partial injection occurred on attempted ERCP. Since its introduction in 1974, PTC has evolved into numerous therapeutic interventions including stenting, stone removal, and in rare cases, even sphincterotomy. In the setting of acute cholangitis, the initial procedure is limited to drainage of the obstructed system. Definitive therapy with stone removal can be achieved on subsequent procedures. A wire may be placed through the transhepatic access and into the duodenum allowing for endoscopic stone removal; this is referred to as a rendezvous procedure. If endoscopic access to the biliary system is not possible, a series of procedures is typically required involving upsizing of drains and various methods of lithotripsy.

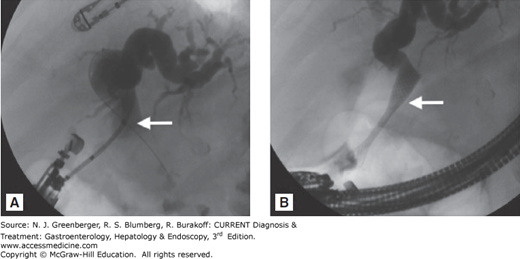

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) may also be used to access the biliary system and perform a rendezvous procedure, and is becoming more widely performed. In this procedure a 19-gauge fine-needle aspiration (FNA) needle is used to access the bile duct via a transduodenal or transgastric approach. Following aspiration, contrast may be injected through the needle and a wire passed. If the wire is placed successfully through the papilla and into the duodenum, it may be used to guide retrograde access and perform a rendezvous procedure. If the wire is unable to pass from the duct and into the duodenum, a stent may be placed antegrade into the bile duct (choledochoduodenostomy) as a temporary measure (Figure 33–1).

Gallstones and their complications occur at increased rates during pregnancy because of decreased gallbladder motility and increased concentration of cholesterol in bile. Acute cholecystitis is the second most common indication for surgery in the pregnant patient, after appendicitis. If the diagnosis of choldedocholithiasis is not clear, MRCP is considered safe and does not require gadolinium, which is known to cross the placenta. In general, the management of pregnant patients with choledocholithiasis and cholangitis is the same as nonpregnant patients. Goal-directed management of sepsis, including antibiotics, and ERCP are considered standard of care. However, the choice of antibiotic regimen, as well as radiation exposure and lead uterus shielding during ERCP should be carefully considered to prevent toxicity to the fetus. ERCP without fluoroscopy may be considered especially in the first trimester, when the fetus is most susceptible to defects in organogenesis.

[PubMed: 17392627]

[PubMed: 14722561]

[PubMed: 17640584]

Surgical biliary drainage carries significant risk of morbidity and a mortality rate as high as 40%. A surgical choledochotomy and T-tube drain placement has lower mortality than cholecystectomy with common bile duct exploration, however the risk is still greater than nonoperative biliary drainage. Operative management should be strictly reserved for cases in which endoscopic or percutaneous methods fail.

GALLSTONE PANCREATITIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is guided by clinical picture and imaging studies (eg, MRCP).

Endoscopic drainage and papillotomy are reserved for suspected ascending cholangitis, established choledocholithiasis, or deteriorating course.

Gallstone pancreatitis is defined as acute pancreatitis with clinical evidence of gallstones, in the absence of other causes of pancreatitis. A clinical definition is needed for this condition, since calculi are often challenging to demonstrate by abdominal imaging during an acute attack, and frequently pass spontaneously into the bowel. Although this is the most common cause of acute pancreatitis, the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, and in up to 30% of patients with acute pancreatitis, the cause is considered idiopathic.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the development of gallstone pancreatitis.

Gallstones can be identified in the stool of up to 94% of patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis compared with only 10% in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis and no history of pancreatitis. The bile reflux theory, first postulated by Lancereaux in 1899, suggests that as stones pass through the ampulla it is disrupted allowing reflux of bile, and other duodenal contents, into the pancreatic duct with subsequent intraglandular pancreatic enzyme activation.

The association of an impacted gallstone at the ampulla of Vater and fatal acute pancreatitis, first described by Opie in 1901, prompted the development of the common channel theory. This theory suggests that impaction of a stone at the ampulla of Vater leads to increased biliary pressures that exceed pancreatic duct pressure, with secondary reflux of bile into the pancreatic duct. This theory is weakened by the fact that some patients do not have common channels, and by studies that have shown sterile bile does not activate proteolytic enzymes. Nevertheless, infected bile is a potent stimulator of these enzymes due to the presence of bacterial amidase and the theory remains popular.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree