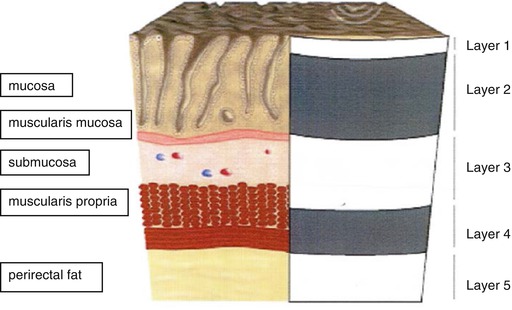

Fig. 19.1

Ultrasonographic anatomy of the normal rectal wall

Fig. 19.2

Schematic overview of anatomy of the normal rectal wall

At the anterior side, the urinary bladder, prostate and seminal vesicles can be identified in men. In women, the urinary bladder, uterus and vagina can be identified but less well appreciated.

Lymph Nodes

Endosonographically, lymph nodes appear as round or oval structures that are hypoechoic compared with the surrounding perirectal fat [16]. It is difficult to differentiate between benign and metastatic lymph nodes by ERUS. Consequently, a number of criteria are used for identifying metastatic lymph nodes as proximity to tumour, hypoechogenicity, round shape and size larger than 3 mm or 5 mm [13, 17].

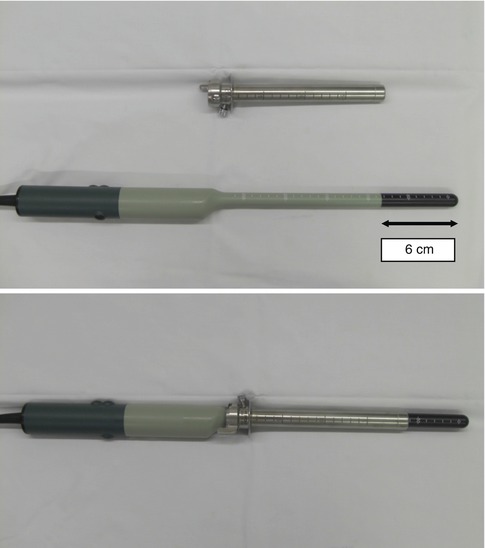

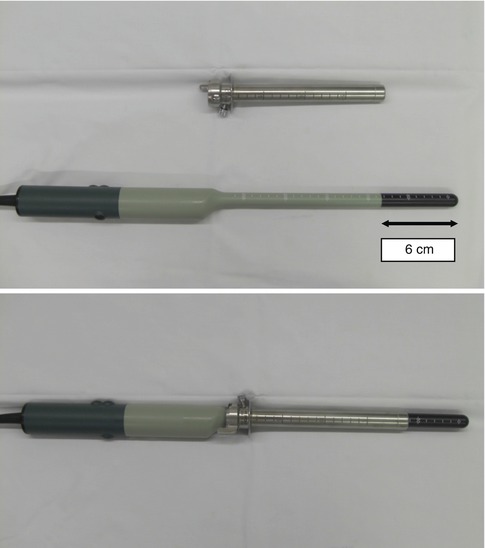

Equipment

In literature, mostly Brüel and Kjaer (Brüel & Kjaer Medical Systems Inc., Naerum, Denmark) equipment is used. In our hospital, we used up to 2007 the B&K Medical Scanner® type 2001 with a type 1850 endoscopic probe with a 10-MHz crystal. Recently, we changed to the B&K Medical Scanner® type 2052 Pro Focus with a type 2052 rotating endosonic probe with a 10–16-MHz transducer (Fig. 19.3). Inside the transducer is a double-crystal assembly where 2 crystals located back to back. The assembly can rotate inside the transducer to give a 360° field of view and can be moved forwards and backwards by control buttons over a length of 6 cm within the distal, black-coloured part of the shaft of the probe. An additional feature is the possibility to compose 3D reconstructions. A balloon is placed over the transducer and is filled with approximately 50 ml of water for optimal acoustic coupling. Alternatively, one can simply fill water into the rectum and use the hard anal probe without balloon. It is important to use degassed water to avoid artefacts on the ultrasound image.

Fig. 19.3

BK Medical 2052 Pro Focus scanner with type 2050 endosonic probe

Technique

Patients can be investigated in an outpatient setting, preferably in a specially designed colorectal unit. One to two hours before endorectal ultrasonography (ERUS), a cleansing enema is given to prevent reduced visibility by stool and avoid artefacts on the images. Patients are placed in lithotomy position, or left lateral decubitus position. First, digital rectal examination is performed to determine sphincter tone and, if within reach of index finger, tumour size, position, mobility and distance from anal verge. Next, a rigid rectoscope (RectoLution® System, Richard Wolf Medical Devices, Knittlingen, Germany), with an outer diameter of 23 mm, is introduced for inspection of the tumour (Fig. 19.4). The rectoscope is then positioned proximal to the upper margin of the tumour, followed by the removal of the inner tube with hand piece. The endosonic probe, with a diameter of 20 mm, is introduced via the rectoscope with the tip of the probe just outside the rectoscope. The rectoscope is then pulled back over the remaining 6 cm of the endosonic probe. Consequently, the distal 6 cm of the probe, coloured black and containing the 10–16-MHz transducer, is outside the rectoscope at the level of the tumour (Fig. 19.5). The balloon is now filled with degassed water for acoustic coupling. Ultrasonographic examination of the entire tumour is now performed and documented in a data file.

Fig. 19.4

RectoLution system 3 rectoscope

Fig. 19.5

Rectoscope with endosonic probe

Staging of Rectal Tumours

ERUS for Differentiating Between Rectal Adenoma and Carcinoma

Local excision of rectal tubulovillous and villous adenomas (TVA) is a validated treatment modality. Concern has been made regarding local recurrences, but with the introduction of transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), the risk has become minimal, and even larger and more proximal located TVA can be excised [18, 19]. In these larger, presumed benign, rectal lesions, based on preoperative biopsy, definite histopathology reveals carcinoma in 21–34 % of tumours [5–7]. When an invasive carcinoma is misdiagnosed as a benign TVA, a suboptimal procedure may be performed for a potentially curable malignant tumour [20]. Although evidence is lacking, previous local excision may burden immediate radical surgery with possible higher morbidity, including increased risk of a (permanent) stoma. Moreover, patient’s satisfaction is impeded by this unexpected histopathologic finding and the need for additional surgery. Finally, oncologic outcome in this subgroup of patients is questionable [21, 22].

Extensive efforts have been made to improve preoperative diagnosis of rectal tumours, with computerized tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ERUS. Two large meta-analysis studies found ERUS to be the most accurate modality when compared with CT and MRI in the assessment of wall penetration of rectal cancer [11, 23]. Results in differentiating adenoma from carcinoma were not mentioned. In a retrospective analysis by Zorcolo et al., 81 patients treated with TEM for rectal tumours were investigated [24]. Of these, 21 cases with preoperative biopsy showing adenoma presented foci of carcinoma at final pathology. In 13 of these (62 %), infiltration of the submucosal layer was correctly demonstrated by ERUS. In a prospective study by Doornebosch et al., 264 patients with preoperative diagnosis of TVA (by tissue biopsy) were included [7]. In 231 tumours, endorectal ultrasonography was technically feasible. Of these 231 assessable tumours, ERUS was considered conclusive in 210 tumours (91 %). All patients were operated and definite histopathologic staging revealed TVA in 166 tumours (79 %), while 44 tumours were diagnosed as invasive carcinoma (21 %). Overall accuracy of ERUS was 84 %. ERUS correctly staged 147 tumours as TVA, with a corresponding sensitivity of 89 %. ERUS correctly staged 38 tumours as invasive with a corresponding sensitivity of 86 % (Table 19.1). With ERUS, the rate of missed carcinomas could be reduced from 21 to 3 % (p < 0.01).

Table 19.1

Agreement of preoperative endorectal ultrasonography with definitive histopathologic stage (Doornebosch et al.) [7]

Histopathologic T-staging | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

pTVA | pT1 | pT2 | pT3 | Total | |

ERUS T-staging | |||||

uTVA | 147 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 153 |

uT1 | 14 | 22 | 4 | 0 | 40 |

uT2 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 13 |

uT3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

Total | 166 | 30 | 13 | 1 | 210 |

Concluding, ERUS is of value in determining treatment strategy for rectal tumours.

ERUS for Staging of Rectal Carcinoma

In the majority of rectal cancer treatment, total mesorectal excision (TME) is the gold standard. This optimized and standardized surgical technique, combined with preoperative radiotherapy, has improved outcome [25, 26]. The prognosis of rectal cancer is closely related to the stage at diagnosis and the choice of treatment. Colorectal staging is currently based on clinical parameters, including degree of invasion of the intestinal wall, degree of lymph node involvement and the existence or not of metastases (TNM classification) [9, 10]. For rectal cancer, the circumferential resection margin is also an important prognostic factor [27]. For T1 rectal carcinomas, TEM is safer than TME, and survival is comparable, although local recurrence rate after TEM can be substantial (4–24 %) [1–4].

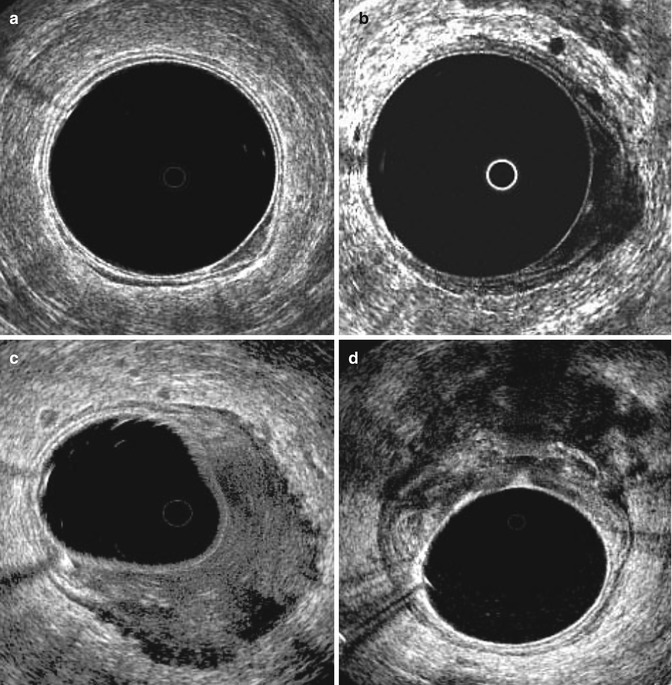

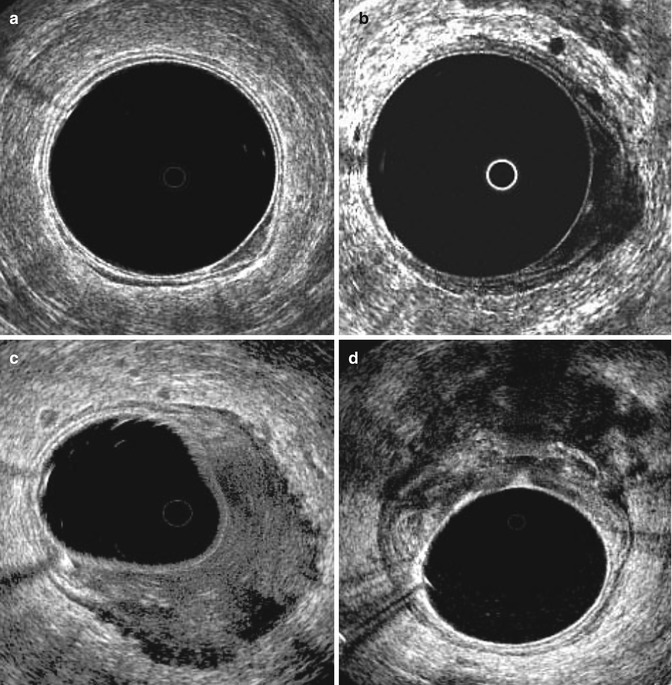

ERUS is a reliable method to stage rectal cancers preoperatively for degree of invasion of the rectal wall. Rectal cancer usually appears as a hypoechoic lesion that disrupts the normal five layer rectal wall structures (see Fig. 19.6a–d). Drawbacks are the inability to diagnose distant lymph node and liver metastases and to determine the circumferential resection margin. Hildebrandt and Feifel proposed a modification of the TNM system to stage rectal cancer by ERUS (Table 19.2) [14]. The prefix u is used to indicate the use of ultrasound.

Fig. 19.6

Endoscopic ultrasonographic images of rectal cancer. (a) shows uT1 lesion, (b) uT2 lesion, (c) uT3 lesion and (d) uT4 lesion (with ingrowth in the vagina)

Table 19.2

Staging of rectal cancer by endorectal ultrasonography

uT0 | Confined to the mucosa |

uT1 | To but not through the submucosa |

uT2 | Into but not through the muscularis propria |

uT3 | Through the bowel wall into the perirectal fat |

uT4 | Involving adjacent structures |

uNo | No definable lymph nodes |

uN1 | Ultrasonographically apparent lymph nodes |

In a meta-analysis by Kwok et al. [23], in determining rectal wall penetration, the sensitivity of ERUS was 93 % and specificity 78 %. In a meta-analysis by Bipat et al. [11], for muscularis propria invasion (uT2), ERUS had a sensitivity of 94 % and a specificity of 86 %. For perirectal fat infiltration (uT3), sensitivity and specificity were 90 and 75 %, and for adjacent organ invasion (uT4) 70 and 97 %, respectively.

Regarding lymph node involvement, ERUS is less accurate. In determining nodal involvement by tumour, the sensitivity of ERUS was 71 % and specificity 76 % in the study by Kwok et al. Bipat et al. showed sensitivity and specificity of 67 and 78 % respectively concerning lymph node involvement. A study by Landmann et al. found an overall accuracy of 70 % for nodal staging, with a 16 % false-positive and 14 % false-negative rate [17]. They observed that size of nodal metastases is related to pT stage and that the ability of ERUS to correctly identify nodal disease was related to the size of the affected lymph nodes and metastatic deposits. Early rectal cancers (T1 and T2) are more likely to have small lymph node metastases (diameter smaller than 3 mm) that are not easily identified by ERUS.

ERUS for Restaging Rectal Carcinoma After Neoadjuvant Therapy

Patients with locally advanced rectal carcinoma are commonly treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by resection. This approach is aimed to downsize and/or downstage rectal cancers with intention to enhance resectability, allow sphincter-preserving surgery, reduce local recurrence and improve long-term survival. ERUS can be used to restage rectal carcinoma after neoadjuvant therapy, although accuracy is questionable. Neoadjuvant therapy can lead to tumour regression and necrosis and fibrotic and inflammatory changes in the rectal wall [28], which can lead to misinterpretation of ERUS images. In a study by Mezzi et al., after neoadjuvant chemoradiation, ERUS correctly classified 46 % (18/39) of patients in line with their histological T-stage [29]. Radovanovic et al. found a good accuracy rate for staging rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation (75 %) [30]. However, ERUS could not identify complete pathological response.

Overall, there is little literature concerning restaging after neoadjuvant treatment, and it appears very difficult.

ERUS for Follow-Up After Resection of Rectal Tumours

In patients treated for rectal cancer with local resection, local recurrence occurs in 4–24 % [1–4], usually within the first 2 years after resection. Because local recurrences also arise extraluminally, ERUS may be useful in detection of recurrences when no mucosal lesions are seen during rectoscopy. In a study to recurrences after TEM for T1 rectal cancer by Doornebosch et al., 18 local recurrences occurred [31]. Of these, 6 were found extraluminally and were only visible with ERUS. In a prospective study in 275 patients with invasive rectal cancer treated with local excision or TME, 48 patients (17 %) developed local recurrence [32]. Of these patients, 30 (63 %) were asymptomatic. ERUS detected one-third of these asymptomatic local recurrences that were missed by digital examination or proctoscopic examination. Muller et al. also found ERUS to be highly sensitive (>90 %) in detecting local tumour recurrence [33].

In our hospital, ERUS is used for the follow-up of patients with T1N0 rectal carcinoma, treated with TEM with curative intent. In the first 2 years, digital examination, rectoscopy and ERUS are performed every 3 months, hereafter every 6 months for 3 years and then annually for another 5 years. The regimen of ultrasonography of the liver and pelvic MRI is the same as patients with more advanced cancer, treated with TME.

Limitations

The accuracy of tumour and nodal staging depends on the experience and expertise of the operator [34, 35]. One study showed that at least 50 examinations are required before the operator reaches optimal accuracy [36].

Another problem with ERUS is difficulty in interpreting differences between different stages in rectal wall penetration. ERUS tends to overstage cancer due to inflammatory infiltrate adjacent to the tumour, that is, endosonographically indistinguishable from the tumour itself [37]. Understaging may be caused by failure to detect microscopic cancer invasion. Preoperative radiotherapy and previous biopsies also diminish the accuracy of T-staging.

If ERUS is considered essential in preoperative staging, accuracy however is not the only relevant issue. Feasibility in all rectal tumours is equally important. If the tumour cannot be reached or passed completely during rectoscopy, or if technical problems occur, such as inability of cleansing the rectum or equipment failure, the tumour is considered not assessable. In series of our hospital, ERUS, with the help of a rigid rectoscope, was technically feasible in 86 % of all rectal tumours. If not feasible, distance from the dentate line (higher percentage in more proximal tumours) proved to be a significant contributing factor [7]. Proper interpretation of ERUS imaging was possible in 78 % of all tumours. The only significant factor negatively influencing interpretation in ERUS imaging was residual or recurrent disease, especially after recent (endoscopic) manipulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree