Fig. 1.1

The Baghdad Battery (Parthian battery) from the village of Khuyut Rabbou’a, near Baghdad, Iraq (Reproduced with permission from W. Koenig, Im verlorenen Paradies, R. Rohrer, Baden b. Wien, 1940)

However, Paul T. Keyser [2] suggested an alternative use of these electric batteries. He points out that considering the use of electric eels to numb an area of pain, or to anesthetize it for medical treatment, these batteries were used as an analgesic treatment in areas (like the Persian Gulf or the rivers of Mesopotamia) where electric fishes were not present, perhaps with conductive acupuncture needles in bronze or iron.

Acupuncture was already a standard practice in Chinese medicine since at least the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BC) and is described in the Huangdi Neijing (The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon or The Inner Canon of Huangdi), variously dated, but no later than the first century AD, and this may explain the fact that bronze and iron needles are found with the Seleucian batteries.

There is evidence that electroichthiotherapy persisted elsewhere throughout the Middle Ages. Indeed as late as the 16th century, the hapless torpedo was found to be efficacious in the relief of chronic headache, unilateral headache, and vertigo. A seventeenth-century traveler to Ethiopia reported how patients suffering the ague were “Bound hard to a table, after which the fish being applied to his joints, causeth the most cruel pain all over his members, which being done the fit never returns again”[3, 4].

In the seventeenth century, however, the discovery of how to produce electrostatic electricity replaced the need for the living organism.

1.3 Franklinism, Galvanism, and Faradism: The Golden Age (1750–1900)

In 1650, Otto von Guericke built an electrostatic machine containing a sulfur ball rubbed by hand, and it was considered the first primitive form of frictional electric machine.

Since the middle of the eighteenth century, electrostatic machines were used in medicine to generate numbness.

The first recorded observation of the use of electricity specifically for medical purposes in Europe was attributed to Christian Kratzenstein, professor of medicine at Halle. The patient was a woman who suffered from a contraction of the little finger; after a quarter of an hour of electrification, the condition was reported as cured. Whatever the permanent effect on the finger may have been, Kratzenstein also noted the acceleration of the pulse rate as a sequel to electrification (Abhandlung von die kraft der Electricitat der Arzeneiwissenschaft–1744).

Jean Jallabert, professor of physics at Geneva, could be regarded as the first scientific electrotherapist, because in 1747 he effected some improvement in a locksmith’s arm that had been paralyzed for 15 years. Jallabert noted that when sparks were drawn from the arm, muscle contractions were noted (Expériences sur l’électricité avec quelques conjectures sur la cause de ses effets, Genève, 1748). Even if the cause being recorded as a blow from a hammer, the man was also lame in the leg of the same side, so it seems probable that the case was one of genuine hemiplegia.

Jallabert continued his experiments on local muscular stimulation, and it could be considered the precursor of Duchenne, who published his results a century later and who used the induced current for effecting muscular stimulation.

A few years later (1752), the American scientist and politician Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) (Fig. 1.2), while he was the US Ambassador to France, used a glass cylinder that generated sparks of static electricity when rubbed for the treatment of a good number of patients and invented the “Magic Square,” a simple form of a condenser capable of giving strong shocks for the treatment of various illnesses.

Fig. 1.2

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) (Engraving by H. B. Hall based on the original portrait painted from life by J. A. Duplessis, from Wikimedia Creative Commons, reproduction considered in the public domain)

The application of static electrical current, characterized by high voltage and low milliampere and produced by a friction generator, was called Franklinism, celebrating the experiment that proved clouds are charged with electricity performed by Benjamin Franklin.

In 1759, Rev. John Wesley published a little work, entitled The Desideratum, in which he sets forth descriptions of some electrical phenomena and recommends the use of electricity as a therapeutic agent.

The earliest work on medical electricity was De hemiplegia per electricitatem curanda, written by Deshais, and published at Montpellier, in 1749, and in 1751 appeared De utditate electrisationis in Arte Medica, which was written by Bohadsch and published at Prague.

In 1791, Luigi Galvani (Fig. 1.3), professor of anatomy at Bologna, announced the results of some experiments started in 1786. The limbs of a freshly killed frog, when placed close to the prime conductor of an electrical machine, were thrown into violent convulsions. Further investigations showed that the leg of the frog, with its attached nerve, formed a delicate indicator for the presence of electricity, more delicate, indeed, than Bennet’s gold-leaf electroscope, which was at that time the most sensitive piece of apparatus known for the purpose.

Fig. 1.3

Luigi Galvani (1737–1798) (From Wikimedia Creative Commons, reproduction considered in the public domain)

Galvani himself was led to an erroneous interpretation as to the result of his experiments, since he regarded the animal body as the source of the electricity and conceived that the metals only served to discharge it. As this type of electricity seemed quite distinct from electrostatic currents derived from frictional machines, it was called Galvanic current.

Galvani’s assumption of “animal electricity” was criticized by Alessandro Volta (1745–1827) (Fig. 1.4), professor of experimental physics at Pavia. He demonstrated that the electricity leading to contraction of the frog muscle was not of animal source but of electrochemical origin. Subsequently in 1800, Volta showed that when two dissimilar metals and brine-soaked cloth are placed in a circuit, an electric current could be produced. This discovery resulted in the invention of the voltaic pile – the first form of a battery.

Fig. 1.4

Alessandro Volta (1745–1827) (From Wikimedia Creative Commons, portrait of physicist Alessandro Volta, in Practical Physics, Millikan and Gale, 1920, considered in the public domain)

In modern times, it has been proven that both were partly right and partly wrong. In fact, when brief electrical stimulation by wires from some external source is applied to a nerve supplying a muscle, it may cause a current to be generated by the nerve itself that can pass a considerable distance from the site of the electrodes to initiate muscle contraction.

In honor of Luigi Galvani, whose work during his Iifetime on animal electricity was eclipsed by the aristocratic Volta, who had honors heaped upon him by Napoleon for his work on electricity from nonliving substances, the use of direct current in medicine is called Galvanism.

As is usual with new remedies, grossly exaggerated accounts of its beneficial effects were circulated, and from about 1803, until after the discovery of electromagnetic induction by Faraday in 1831, the use of electricity as a therapeutic agent largely fell into disrepute. It had been vaunted almost as a specific treatment for different nervous disorders, paralytic affections, deafness, some kinds of blindness, the recovery of the suffocated and drowned, and even for hydrophobia and insanity [5].

Benjamin Franklin, who had at least two accidents that resulted in electricity passing through his brain, witnessed a patient’s similar accident and performed an experiment that showed how humans could endure shocks to the head without serious ill effects, other than amnesia. Jan Ingenhousz, Franklin’s

Dutch-born medical correspondent better known for his discovery of photosynthesis, also had a serious accident that sent electricity though his head and, in a letter to Franklin, he described how he felt unusually elated the next day. During the 1780s, Franklin and Ingenhousz encouraged leading French and English electrical “operators” to try shocking the heads of melancholic and other deranged patients in their wards. Although they did not state that they were responding to Ingenhousz’s and Franklin’s suggestions, Birch, Aldini, and Gale soon did precisely what Ingenhousz and Franklin had suggested [6].

ln 1802, for example, Aldini (Galvani’s nephew), professor of natural philosophy at Bologna, reported one of the earliest uses of electricity in treating severe depression and found that although the pain of the Galvanic shocks was hard to bear, the best site for producing relief of depression was on the head itself, particularly over the parietal region [7, 8].

This could be considered as the first form of electroconvulsive therapy (formerly known as electroshock), then reintroduced in 1938 by Italian neuropsychiatrists Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini as a therapeutic option for severe depression, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric disorders [9], and that, despite the controversial and violent idea transmitted in the years by cinema or literature, gained widespread popularity among psychiatrists as a form of treatment in the 1940s and 1950s and still find some accepted indications.

In 1803, Aldini published a treatise on “Galvanism”; among other experiments recorded, there was one in which he applied the terminals of a powerful battery to the body of a criminal hanged at Newgate and recorded extraordinary convulsions and facial contortions as a consequence of the stimulation [10].

In 1811, the composer and physician Hector Berlioz suggested the combination of classic Chinese method of acupuncture (introduced into France by Jesuit missionaries returning from China in 1774) with electrotherapy. He mentioned that “apparently the application of Galvanic shock produced by the voltaic pile heightens the medical effect of acupuncture.”

In 1823, the French physician Jean-Baptiste Sarlandière argued that “All lesions of motion should be treated by Fraklinism and all those of sensation should be treated by Galvanism” and in 1825 demonstrated that the effect of Galvanism could be enhanced by the use of acupuncture needles leading to the first development of electroacupuncture. He resumed: “in my opinion electro-acupuncture is the most proper method of treating rheumatism, nervous afflictions and attacks of gout” and about his method: “introduces shock into the very place I wish and this able to modify pain, motion or capillary circulation…As I have said, even the lightest discharges upon the needle introduced into our tissue will cause a feeling of vibration all through the suffering part. If this part is a muscle, one can feel, and even see, the contraction through the skin. Heavy discharges result in a sort of convulsion and, by its being suddenly shaken in this way, the nervous functions of a suffering part are modified and pain is relieved” [11].

Also Magendie performed electroacupuncture in the early nineteenth century, mentioning remarkable cures (but never failures and accidents) from the use of platinum and steel needles plunged into muscles, nerves, and even through the eyeball into the optic nerve and connecting them to a battery [12].

In 1835 also Guillaume Duchenne began experimenting with therapeutic “electropuncture.”

However, the application of Galvanic current was not without side effects. Its prolonged use led to necrotic changes in the tissues. This damaging action was later employed (in Victorian times) for the destruction of superficial tumors.

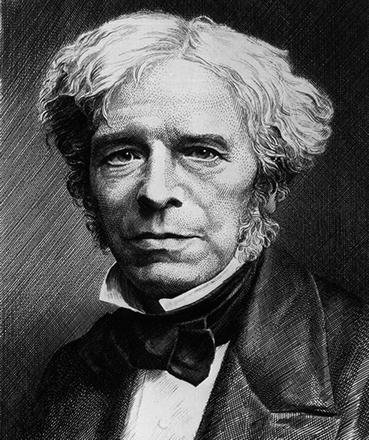

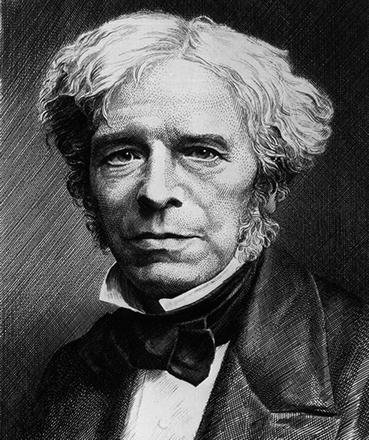

The British scientist Michael Faraday (1791–1867) (Fig. 1.5) in 1832 employed the voltaic pile and discovered that the flow of electricity could be induced intermittently and in alternate directions. The use of this current was called Faradism. He connected an inner or primary coil of wire to his voltaic pile, and as soon as the circuit was switched on, electricity flowed in one direction through an outer or secondary coil of wire (not connected to the first). When the primary current was switched off, the current in the secondary coil flowed in the opposite direction. By this means, Faraday established the possibility of introducing powerful currents of alternating polarity using a relatively weak direct current source. The advantage of this method is that a stimulation performed with a short pulse duration (<1 ms) should prevent any risk of tissue damage, because there is insufficient time for the electrolytic effect to develop.

Fig. 1.5

Michael Faraday (1791–1867) (From Wikimedia Creative Commons, portrait of Michael Faraday, in Practical Physics, Millikan and Gale, 1920, reproduction considered in the public domain)

The most important promoter of Faradism in the mid-nineteenth century was the French physician Guillaume Duchenne, who used this technique in particular for muscle stimulation.

In 1849 he stated: “Faradism is the best form of muscular electricity and can be practiced frequently and for a long time… The results are of highest importance” [13, 14].

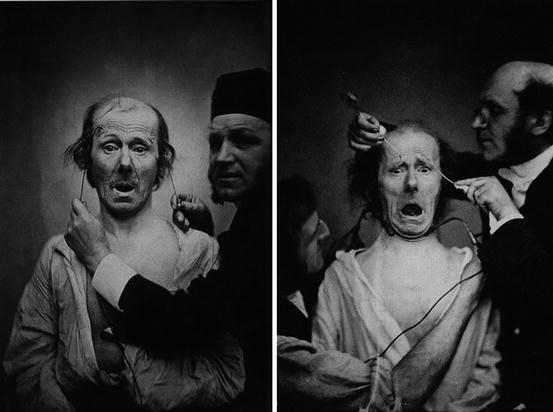

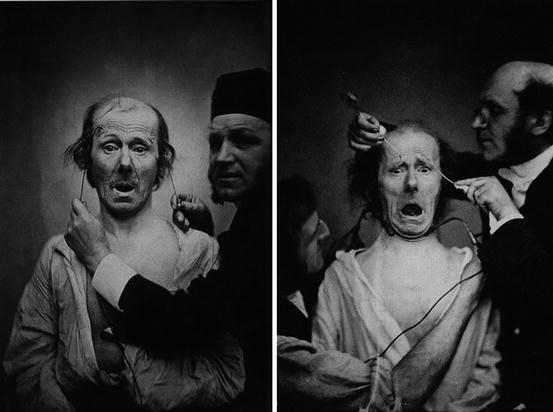

Influenced by the fashionable beliefs of physiognomy of the nineteenth century, Duchenne wanted to determine how the muscles in the human face produce facial expressions which he believed to be directly linked to the soul of man (Fig. 1.6). He is known, in particular, for the way he triggered muscular contractions with electrical probes, recording the resulting distorted and often grotesque expressions with the recently invented camera. He published his findings in 1862, together with extraordinary photographs of the induced expressions, in the book The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy (Mecanisme de la physionomie Humaine).

Fig. 1.6

Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne performing facial electrostimulus experiments (From Wikimedia Creative Commons, photographic portrait of Duchenne by A. Tournachon, reproduction considered in the public domain)

Throughout the nineteenth century, the analgesic effects of electricity were widely popular and enjoyed their “golden age.” Electrotherapy was used for countless dental, neurological, psychiatric, and gynecological disturbances.

However, it was even used by quacks and charlatans.

Judah Moses, of Hartford, CT, received the first US patent for “galvanic spectacles” in 1868. Most of these spectacles relied on a small zinc and copper plate to generate the tiny current desired. This current was delivered to the wearer at the bridge or nosepieces, where it was thought to reach the optic nerves. The medical benefit of applying an electric current to the optic nerve was usually not specified in these patents; however, strengthening eyesight and allowing the user to read for a longer time were claimed in Smith and Martin’s patent in 1889.

With regard to these unserious applications and to the advance of effective analgesic drugs, besides the difficulties and cost in producing reliable machines, the lack of knowledge of the working method, the ideal stimulus parameters, and the ideal location and size of electrodes, electricity has progressively fallen out of favor.

1.4 Revival of Electrotherapy for Pain and Pelvic Floor Disorders

In the second half of the twentieth century, the scientific bases of electrotherapy were increasingly elucidated, offering the chance for a rational treatment of various conditions. Studies of electrotherapy have been developed mainly for the purpose of treating pain. With the publication of their “gate control theory” of pain modulation in 1965, Wall and Melzack provided a conceptual mechanistic foundation for considering direct electrical stimulation of the spinal cord and peripheral nerves as a potential treatment for chronic pain [15].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree