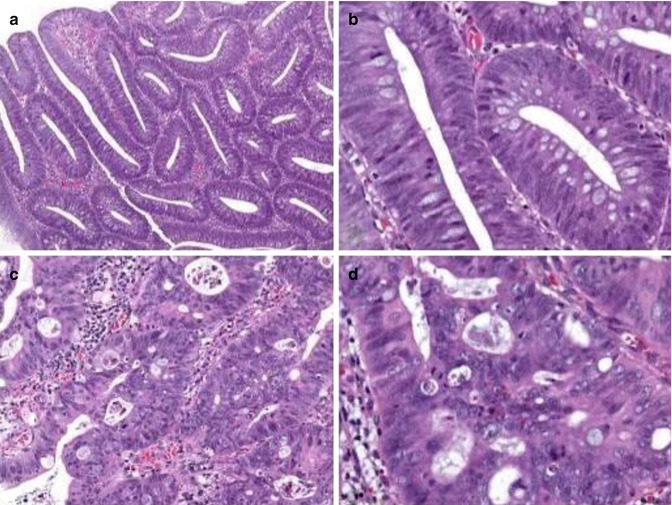

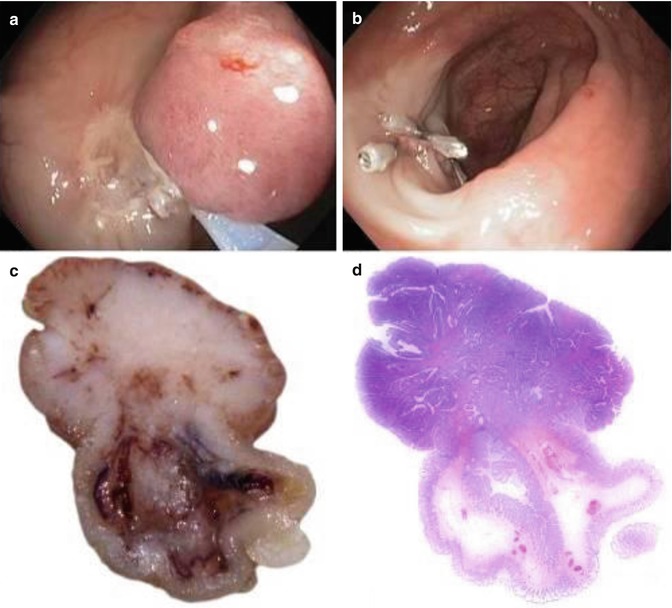

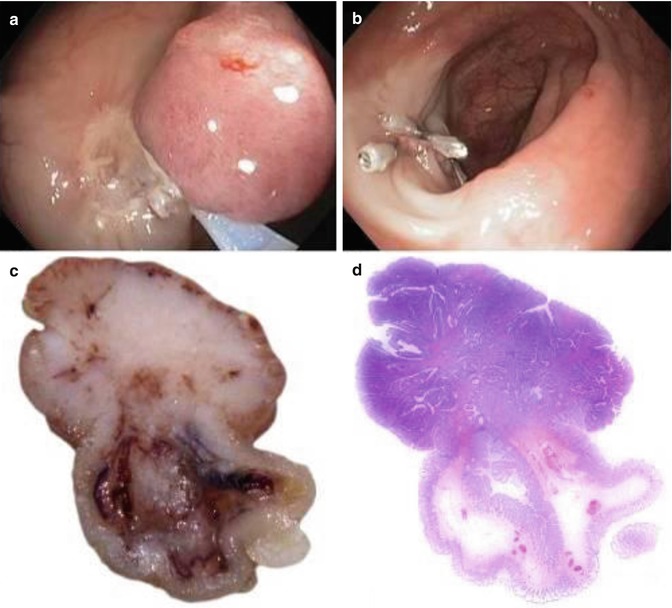

Fig. 21.1

Sessile serrated adenoma (a) showing marked structural alterations such as hyperserration, columnar dilatation and serration in the lower third of the crypts with crypt branching and formation of L- and T-shaped crypts above the muscularis mucosae. Traditional serrated adenoma (b) showing a serrated morphology but also classical (cytological) features of intraepithelial neoplasia/dysplasia

Notably, both the Kyoto classification [4, 12] and the European guidelines of colorectal carcinoma screening [7, 8] recommend the use of the term sessile serrated lesion for these lesions based upon the lack of classical (cytological) features of intraepithelial neoplasia/dysplasia. However, in the 2010 edition of the WHO classification, the term sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) is recommended [9], even though these lesions are flat, belonging to the group of non-polypoid colorectal lesions.

Diagnosis of “serrated (historically hyperplastic) polyposis” should be considered in cases with (1) at least five histologically proven serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon with two or more of these exceeding 10 mm in size; (2) any number of serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon in an individual who has a first-degree relative with serrated polyposis; or (3) if more than 20 serrated polyps of any size are found distributed throughout the colon [9].

Mixed Polyp

According to current WHO guidelines, these are combinations of serrated lesions (mainly sessile serrated adenomas, rarely hyperplastic polyps) with conventional (tubular, tubulovillous, villous) as well as traditional serrated adenomas [9]. They were interpreted as collision tumours in the past. Nowadays, these lesions are considered serratedlesions, in particular SSA/Ps complicated by intraepithelial neoplasia/dysplasia, thereby indicating neoplasticprogression on the serrated route to cancer. Of note, both the European guidelines for colorectal cancer screening [7, 8] and the proposal of diagnostic criteria for serrated lesions presented by members of the Working Group of Gastrointestinal Pathology of the German Society of Pathology [13] recommend to first describe the components of the “mixed polyp” and then include the term mixed polyp in parentheses, e.g. sessile serrated adenoma and tubular adenoma (mixed polyp) with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia/dysplasia. As classical adenomas, these lesions should be removed completely.

Traditional Serrated Adenoma

Polyps that show a serrated morphology, but also classical (cytological) features of intraepithelial neoplasia/dysplasia, are termed traditional serrated adenomas (Fig. 21.1b). These lesions were recognised as a distinct entity by Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser already in 1990 [14] and were given the name serrated adenoma at that time. They are rare and usually encountered in the left colon. In order to avoid confusion with sessile serrated adenomas, they were later given the name “traditional” serrated adenoma. Treatment and surveillance are considered to be the same as for classical (tubular, tubulovillous, villous) adenomas.

Grading of Intraepithelial Neoplasia/Dysplasia

Grading of a neoplastic lesion aims at translating biology, i.e. the multistep progress described in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, into different levels of risk for progression and/or aggressiveness. It has to be noted that there is considerable interobserver variation in the final diagnoses worldwide, mainly due to poorly defined criteria and/or varying interpretation of criteria, causing different assessment of a lesion among different pathologists.

The Vienna classification aimed to group diagnoses with the same clinical consequences together in order to minimise interobserver variation. The system also improved the accuracy of biopsy diagnoses by minimising discrepancies between diagnoses obtained from biopsy material and subsequent resections, respectively [15]. One disadvantage is the use of several subcategories. The Kyoto classification [4, 12] and also the European guidelines of colorectal carcinoma screening [7, 8] recommend a revised scheme of the Vienna classification meant to further simplify the system. These recommendations led to a 4-tiered system: no neoplasia, low-grade mucosal neoplasia (low-grade adenoma), high-grade mucosal neoplasia (high-grade adenoma, mucosal carcinoma) and carcinoma infiltrating the submucosal layer or beyond. This revision caused increased attention for intramucosal carcinoma and was felt to be a compromise, bringing Western and Asian standpoints closer together. The future will show whether these pragmatic approaches will become more accepted worldwide than previous systems.

Low-Grade Intraepithelial Neoplasia/Dysplasia

Low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia is an unequivocal neoplastic condition confined to the glandular epithelium, not to be mistaken for inflammatory or regenerative changes. The earliest morphological precursor of intraepithelial neoplasia is the aberrant crypt focus (ACF), i.e. a “single-crypt adenoma” [16]. Microscopic examination of mucosal sheets dissected from the bowel wall in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis or mucosal examination with a magnifying endoscope reveals ACFs to have crypts of enlarged calibre and thickened epithelium with reduced mucin content [16]. Progression from ACF through adenoma to adenocarcinoma characterises carcinogenesis in the large intestine. The situation is more complex in individuals with chronic inflammatory bowel disease in which the diagnosis of a sporadic adenoma has clinical implications different from those of colitis-associated neoplasia.

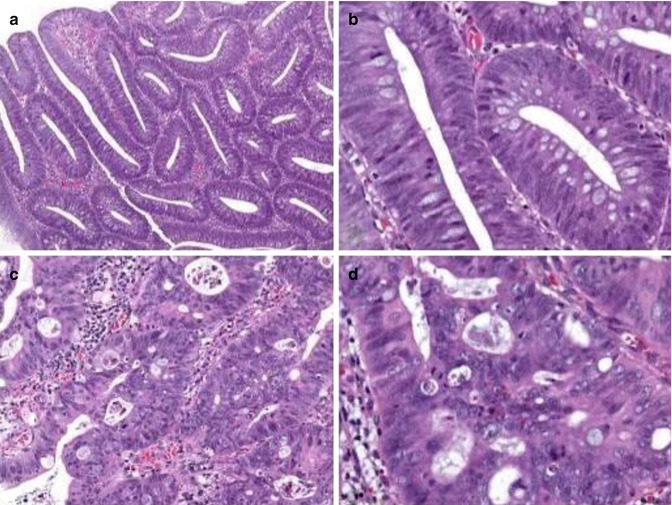

Histologically, lesions characterised by low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia show reduced mucin content (reduced number of goblet cells) with increased cytoplasmic basophilia and a variety of nuclear changes, such as hyperchromasia, enlargement (spindle-like elongation) and pseudostratification (palisading). Although the number of mitotic figures is increased, atypical mitoses are generally not observed, and nuclear polarity is retained (Fig. 21.2a, b).

Fig. 21.2

Grading of intraepithelial neoplasia/dysplasia. Lesions characterised by low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (a, b) show reduced mucin content (reduced number of goblet cells) and a variety of nuclear changes, such as hyperchromasia, spindle-like elongation and pseudostratification. Nuclear polarity, however, is retained. In high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (c, d), complex glandular crowding and irregularity with cribriform gland formation and back-to-back pattern is seen (Note loss of nuclear polarity and distinct nuclear changes such as presence of vesicular markedly enlarged irregular nuclei, often with a dispersed chromatin pattern and prominent nucleoli)

High-Grade Intraepithelial Neoplasia/Dysplasia

Morphological changes suggestive of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia should involve more than just one or two crypts. In addition to the histological characteristics of low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia described above, high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia shows distinctive structural features: complex glandular crowding and irregularity (note that the word “complex” is important and excludes simple crowding of regular tubules that might result from crushing), prominent glandular budding, cribriform gland formation, back-to-back pattern as well as prominent intraluminal papillary tufting. Some of these criteria may be found in low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia/dysplasia as well. This makes it necessary to use further cytological features: loss of cell and/or nuclear polarity and distinct nuclear changes such as vesicular and/or markedly enlarged irregular nuclei, often with a dispersed chromatin pattern and prominent nucleoli. Atypical mitotic figures are common, and prominent apoptosis, giving rise to intraluminal debris, may be found in some cases (Fig. 21.2c, d). Often several of the above-mentioned features are detected within the same lesion. Caution should be exercised if only a single criterion is observed in order to avoid overinterpretation. Since ordinary adenomas do not erode, erosions should always prompt thorough evaluation of an adenomatous lesion not to miss presence of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. However, overinterpretation of isolated surface changes that may be caused by trauma or prolapse needs to be excluded.

Misplacement (entrapment) of adenomatous epithelium into the submucosa of a polyp (pseudoinvasion) represents a well-known histopathological pitfall which needs to be distinguished from invasive carcinoma [17]. If in doubt, the relevant findings should be stated in the pathology report, and a second opinion and/or additional biopsies from the polypectomy site should be considered. Sigmoid polyps are particularly prone to inflammation, a feature which tends to exaggerate the histological features of neoplasia. When associated with epithelial misplacement, the potential for misdiagnosing these lesions as early carcinoma is evident. Histological changes suggestive of epithelial misplacement are acellular submucosal mucin lakes (not to be misinterpreted for mucinous adenocarcinoma) and hemosiderin-laden macrophages within the stroma.

Histological Evaluation of pT1 Colorectal Cancer

According to the AJCC/UICC TNM system [5, 6], pT1 cancers are those showing invasion through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa but not beyond. Once again, it has to be stressed that in Japan the term mucosal carcinoma is used as a diagnostic term to describe a distinct tumour category. The discussion, however, seems to be somewhat academic, since all mucosal high-grade lesions, regardless of the terminology used, are adequately treated by endoscopic removal and are believed not to metastasize.

Definition of Invasion

The danger of surgical overtreatment due to misinterpretation of a lesion as invasive cancer must always be considered in biopsy diagnoses. Postoperative mortality (within 30 days) varies between 5 and 10 % in colonic cancers, depending on the population, age of the patient and quality of services available [18–20].

Achieving the optimum balance between removing all disease by resection and minimising harm is crucial. Since criteria of intramucosal criteria are currently not well defined in columnar epithelium, we strongly recommend to adhere to the definition given by the WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system [3], which regards invasion of neoplastic cells through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa as prerequisite for diagnosing invasive adenocarcinoma at this site (Fig. 21.3a). It needs, however, to be recognised that diagnoses made on the basis of this definition will hamper comparison with series from Japan for which the diagnosis of intramucosal adenocarcinoma is possible. Of note, the AJCC/UICC TNM classification scheme [5, 6] allows to use the term carcinoma in situ (pTis) in columnar epithelium, but as pointed out above, this category is rather vague and ill defined, and, therefore, its use is discouraged by the European guidelines on colorectal cancer screening [7, 8].

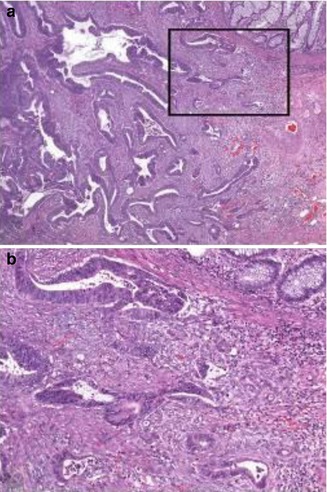

Fig. 21.3

Early colorectal cancer showing invasion of neoplastic cells through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa (a). Note desmoplastic stromal response around invading glands in high-power view (b)

Histological criteria of invasion, such as single tumour cells, are more likely to be seen in advanced carcinomas, but not in early carcinomas. Likewise, a desmoplastic stromal response is only rarely observed, particularly when carcinoma cells have just started to invade the submucosal layer (Fig. 21.3b). In addition, basal membranes are frequently discernible around invading glands in well-differentiated early carcinomas [21–23], and definitions using the term “invasion through the basement membrane” are for this reason misleading. Nevertheless, a subclassification of early carcinomas into low-risk and high-risk categories, based on the estimated risk of regional lymph node involvement, should always be performed.

Typing of Early Colorectal Cancer

Histological typing of colorectal cancers is generally performed according to WHO guidelines and does not differ between early and advanced tumours [3]. Thus, most adenocarcinomas are gland forming, with variability in size and configuration of glandular structures. In well- and moderately differentiated cases, which make up the vast majority of early cancers, the epithelial cells are usually large and tall, and the gland lumina may contain varying amounts of debris. The designation of mucinous adenocarcinoma is used when more than 50 % of the lesion is composed by pools of extracellular mucin. Signet ring cell carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma represent rare variants that are almost never observed as early cancer.

Risk Assessment in pT1 Colorectal Cancer

In early colorectal adenocarcinoma, discussions regarding optimal treatment of affected individuals (endoscopic vs. surgical) appear to be an integral part of multidisciplinary team meetings. To facilitate clinical decision making, the pathologist should always report on histological features that may indicate increased risk of local lymph node spread, thus enabling stratification of tumours into low- and high-risk categories [7, 24–28].

In colorectal adenocarcinoma, in general, several parameters have been correlated with adverse outcome, such as depth of invasion reflected by the AJCC/UICC TNM system, tumour size, tumour differentiation, lymph and blood vessel invasion, perineural invasion, tumour border configuration, incomplete tumour resection and tumour cell dissociation at the invasion front referred to as tumour budding [29–31]. Some of these parameters, e.g. lymph and blood vessel invasion as well as tumour budding, are potential predictors of increased risk of local lymph node spread (compare below).

For early colorectal cancer, the most appropriate method for risk estimation of lymph node involvement appears to be the assessment of depth of invasion which should be assessed depending on the overall morphology of the lesion, e.g. sessile (Kikuchi levels; [32]) or polypoid (Haggitt levels; [33]). Other parameters, such as vascular invasion and tumour budding, may serve as additional markers. In the following, we will refer to the main prognostic parameters in detail. Of note, the value of these markers has very recently been proven in two systematic meta-analyses [34, 35].

Subclassification of pT1 Adenocarcinomas According to Depth of Invasion

For submucosal carcinomas, substaging of pT1 is essential. The most widely used approach implies the pragmatic subdivision of the submucosal layer into three parts: a superficial, a middle and a deep third, also referred to as Kikuchi levels sm1, sm2 and sm3 [32]. The risk of lymph node involvement has been calculated to account for 1.4–5 % for sm1, 8 % for sm2 and 23 % for sm3 tumours, respectively [36, 37]. In polypoid lesions, the stalk always represents the upper third of the submucosal layer. Haggitt et al. [33] identified the level of invasion into the stalk of a pedunculated polyp as being important in predicting outcome. The authors classified polypoid tumours as follows: “level 1” lesions show invasion of the submucosa limited to the head of the polyp, “level 2” lesions extend into the neck of the polyp, “level 3” lesions show invasion of any part of the stalk and “level 4” lesions invade beyond the stalk but still confined to the submucosal layer. An example illustrating the use of the Kikuchi and the Haggitt system is given in Fig. 21.4.

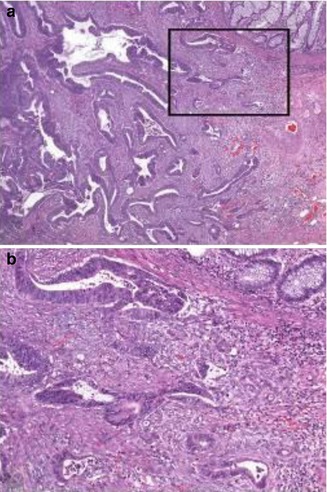

Fig. 21.4

Pedunculated early colorectal cancer. The lesion is completely removed by endoscopy (a, b; Images courtesy of Dr. Franz Siebert, Hospital of Barmherzige Brüder, St. Veit/Glan, Austria); all margins are free of cancer (R0 resection). The cut surface (c–d) shows invasion (marked by an arrow) extending into the upper third of the submucosal layer (sm1), as represented by the neck of the polyp (Haggitt level 2)

It has to be noted that both the Kikuchi (for sessile tumours) and the Haggitt (for polypoid or pedunculated tumours) classification systems may be difficult to apply, especially if there is fragmentation or suboptimal orientation of the tissue. Separation of Haggitt level 2 from levels 1 and 3 may be difficult even if the lesion is well preserved. Moreover, although level 4 invasion is generally accepted as a major risk factor for adverse outcome, regional lymph node metastasis may be observed also in level 2 or 3 lesions.

Thus, recent classification systems stressed the advantage of exact measurement of tumour invasion beyond the muscularis mucosae. Ueno et al. [38] suggested to assess both the depth (cut-off value 2,000 μm) and the width (cut-off value 4,000 μm) of invasion. The authors demonstrated that by doing so, a more objective and accurate assessment of the risk of lymph node metastasis is possible: 3.9 % vs. 17.1 %, when depth of submucosal invasion is lower or higher than 2,000 μm, as well as 2.5 % vs. 18.2 %, when width of submucosal invasion is lower or higher than 4,000 μm. According to other studies, tumours with submucosal invasion not deeper than 1,000 μm generally lack lymph node metastasis, thus rending the 1,000-μm cut-off value as major criterion for stratification of patients for endoscopic or surgical therapy [39, 40].

Each classification system has its advantages and disadvantages: (1) the Kikuchi system cannot reliably be used if the muscularis propria is not present (i.e. in most endoscopic resections), (2) the Haggitt levels are not applicable in non-polypoid (sessile) lesions and (3) exact measurement depends on the feasibility to identify the muscularis mucosae which may be difficult, if not impossible, when cancer tissue has destroyed this histological landmark. Lacking a worldwide consensus, a definitive recommendation for one method or another can currently not be given. The European guidelines of colorectal cancer screening, however, recommend the Kikuchi system for non-polypoid (sessile) and the Haggitt system for polypoid (pedunculated) lesions [5, 6].

Tumour Grade in pT1 Adenocarcinomas

Grading of colorectal cancer is generally performed according to the WHO guidelines assessing the extent of glandular appearance and should be divided into well-, moderately and poorly differentiated or into low-grade (encompassing well- and moderately differentiated cancers) and high-grade (including poorly differentiated and undifferentiated cancers) tumours, respectively [3]. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas should at least show some gland formation or mucus production. When a carcinoma is heterogeneous, grading should be based on the least differentiated component, not including the leading front of invasion. The percentage of the tumour showing gland formation can be used to define the grade. According to the current WHO classification [3], well-differentiated tumours (grade 1) exhibit glandular structures in >95 % of the tumour area, moderately differentiated tumours (grade 2) in 50–95 % and poorly differentiated tumours (grade 3) in >0–49 %, respectively. By convention, morphological grading of tumours applies only to adenocarcinoma “NOS” (not otherwise specified). Other morphological variants (e.g. mucinous adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma) carry their own prognostic significance and grading does not apply [3].

In general, no substantial differences exist between the grading of early and advanced cancers. In the absence of good evidence, the European guidelines for colorectal cancer screening recommend that a grade of poor differentiation should be applied in a polyp cancer when any area of the lesion is considered to show poor tumour differentiation [7]. As for advanced tumours, tumour cell dissociation at the leading edge of invasion (“budding”) should not influence the grading of early cancers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree