Chapter 2 DYSPHAGIA AND ODYNOPHAGIA

DYSPHAGIA

Taking the dysphagia history

A good history will elucidate the site and the general pathophysiological process in 80% of cases, and is vital before embarking on a focussed and cost effective utilisation of specific diagnostic techniques. Frequently, patients will describe food sticking or holding up either retrosternally or in the neck. However, more atypical symptoms can include regurgitation, a sense of fullness retrosternally and hiccup. Dysphagia is distinguished from odynophagia (pain on swallowing) by the perception of actual bolus hold up. The aims of the history are to:

Where does the food stick?

Retrosternal hold-up suggests that the disorder lies within the oesophagus. If the site of hold-up is in the neck, the pathology can lie either in the oesophagus or in the pharynx (Figure 2.1). Due to referred sensation, the site of perceived hold-up is above the suprasternal notch in 30% of cases where the actual hold-up is within the oesophageal body. Therefore, the next batch of questions aims to distinguish pharyngeal from oesophageal dysfunction.

Is one or more of the four cardinal symptoms of pharyngeal dysfunction present?

The four cardinal symptoms of pharyngeal dysfunction are:

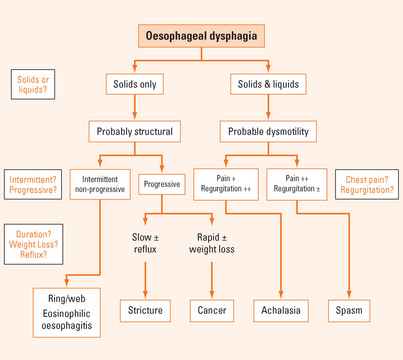

If oesophageal dysphagia is suspected, the next step is to establish whether it is a structural or motor disorder (Tables 2.1 and 2.2).

TABLE 2.1 Structural oesophageal disorders causing dysphagia

TABLE 2.2 Aetiology of pharyngeal dysphagia*

| Structural | Neuromyogenic |

How long has dysphagia been present; is it intermittent, is it progressive?

Longstanding dysphagia is compatible with a benign condition. Slowly progressive, longstanding dysphagia, particularly if reflux is or has been experienced, is highly suggestive of a peptic stricture. A short history of dysphagia particularly with rapid progression (weeks or months) and associated weight loss is highly suggestive of oesophageal cancer. Longstanding, intermittent, non-progressive dysphagia purely for solids is indicative of a fixed structural lesion such as a distal oesophageal ring or proximal oesophageal mucosal web.

Does the patient regurgitate?

While regurgitation can be associated with solid bolus hold-up during a meal, spontaneous regurgitation between meals (generally fluid and ‘frothy’ saliva) is highly suggestive of dysmotility (see below).

Does the patient experience chest pain or discomfort?

If oesophageal dysmotility is strongly suspected, distinction between achalasia and oesophageal spasm can be difficult at times. Achalasia is very much more common than spasm. In achalasia, chest pain is more prominent early in the disease, but over the years tends to diminish and may disappear as dysphagia and regurgitation worsen. In contrast, the chest pain of spasm is the predominant symptom and can be quite severe. Due to poor oesophageal clearance, regurgitation is frequently more impressive in achalasia than it is in the case of spasm. The oesophagus generally dilates over time in the context of achalasia, but this is less prevalent with spasm. Finally, there can be significant overlap between the two syndromes and spasm can evolve into more typical achalasia over time as they both share a similar underlying inhibitory neuropathic process. Oesophageal motility disorders can be classified as either primary (e.g. achalasia or diffuse oesophageal spasm) or secondary (e.g. scleroderma) (Table 2.3).

TABLE 2.3 Classification of oesophageal motility disorders

| Primary | Secondary |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|