Duodenal Peptic Diseases

Peptic Duodenitis

Peptic duodenitis and peptic duodenal ulcers represent different phases in the response to increased acid secretion often as the result of antral predominant H. pylori gastritis. The incidence of duodenal ulcers also increases in cigarette smokers, patients with chronic renal disease, and alcoholics. Disturbed motility also predisposes to active duodenal ulceration due to prolonged mucosal contact with the acid. Factors associated with refractory ulcers are listed in Table 6.4. Severe peptic duodenitis also occurs in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Peptic duodenitis is typically confined to the duodenal bulb. Endoscopic appearances vary from simple erythema to mucosal friability and nodularity. The erythema results from shunting of blood to the villous tips, a change induced by the hydrochloric acid (169). Severe cases exhibit erosions and

ulcers. Alternatively, mucosal atrophy, thickening, or irregularity is present.

ulcers. Alternatively, mucosal atrophy, thickening, or irregularity is present.

TABLE 6.4 Factors Associated with Refractory Ulcers | |

|---|---|

|

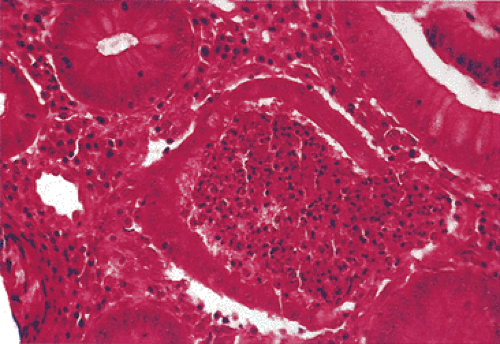

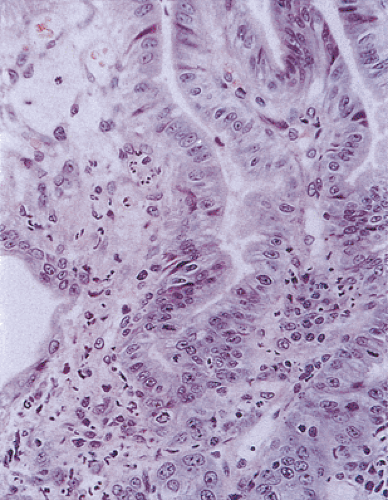

The principal findings of peptic duodenitis include any or all of the following: (a) inflammatory cells in the epithelium or lamina propria; (b) altered enterocyte morphology due to degeneration, regeneration, or the presence of foveolar metaplasia; (c) mucosal hemorrhage and edema; and (d) Brunner gland hyperplasia (Fig. 6.86) and foveolar metaplasia. The foveolar metaplasia may be extensive or patchy in its distribution. The inflammation may include neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Patients may also develop lymphoid hyperplasia (Fig. 6.87). Whitehead et al proposed dividing duodenitis into three grades based on the severity of the inflammation and the villous architecture (170). In the severest form of duodenitis, the villi appear flat (Fig. 6.87). The superficial epithelium and the brush border become progressively less distinct, with nuclear pseudostratification, mucosal erosions, and foveolar metaplasia. Neutrophils extend into the crypts and Brunner gland ducts. Lymphoid aggregates and hyperplasia, vascular dilation, and edema may all be present.

FIG. 6.84. Duodenitis. The epithelium appears very reactive and inflamed. There is syncytial formation. |

The presence of foveolar cell metaplasia (gastric surface epithelial metaplasia) provides a helpful clue to the diagnosis of peptic duodenitis (Fig. 6.87). Foveolar metaplasia probably represents an adaptive response to either duodenal hyperacidity or H. pylori infection (171) and may protect against ulceration because this epithelium has the ability to transport hydrogen ions out of the mucosa back into the GI lumen (see Chapter 4). If H. pylori bacteria are present in the stomach, some may colonize areas of foveolar cell metaplasia in the duodenum via the same specific adherence mechanisms used in the stomach (see Chapter 4). The metaplastic cells are histologically identical to foveolar cells in the stomach, and not surprisingly, they express a gastric mucinous phenotype rather than an intestinal one (171). H. pylori attached to the foveolar cells then contribute to an acute or chronic active duodenitis and the development of duodenal peptic ulcer disease (172). A high density of cagA-positive strains of the bacteria in the patients with severe duodenitis is an important determinant of duodenal ulcer disease (173). The most persuasive argument supporting the dominant role of H. pylori in duodenal ulcer disease is the dramatic decrease in relapse rates after successful cure of the infection, with subsequent healing of the mucosa (174).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree