Disorders of the Ureter & Ureteropelvic Junction: Introduction

The ureter is a complex functional conduit carrying urine from the kidneys to the bladder. Any pathologic process that interferes with this activity can cause renal abnormalities, the most common sequels being hydronephrosis (see Chapter XXX) and infection. Disorders of the ureter can be classified as congenital or acquired.

Congenital Anomalies of the Ureter

Congenital ureteral malformations are common and range from complete absence to duplication of the ureter. They may cause severe obstruction requiring urgent attention, or they may be asymptomatic and of no clinical significance. The nomenclature can be confusing and has been standardized to prevent ambiguity (Glassberg et al, 1984).

The ureter may be absent entirely, or it may end blindly after extending only part of the way to the flank. These anomalies are caused during embryologic development, by failure of the ureteral bud to form from the mesonephric duct or by an arrest in its development before it comes in contact with the metanephric blastema. The genetic determinants of ureteral bud development and the causes of bud abnormalities are being elucidated and it is known that GDNF signaling via the RET receptor is generally required (Michos et al, 2010). In any event, the end result of an atretic ureteral bud is an absent or multicystic dysplastic kidney. The multicystic kidney is usually unilateral and asymptomatic and of no clinical significance. In rare cases, it can be associated with hypertension, infection, or tumor. Contralateral vesicoureteral reflux is common, and many clinicians recommend a voiding cystourethrogram as part of the initial workup. There has been a concern about the risk of malignancy in these cases; however, the preponderance of evidence now suggests that no treatment is necessary and indeed no follow-up is needed from a urological standpoint (Onal and Kogan, 2006).

Complete or incomplete duplication of the ureter is one of the most common congenital malformations of the urinary tract. Nation (1944) found some form of duplication of the ureter in 0.9% of a series of autopsies. The condition occurs more frequently in females than in males and is often bilateral.

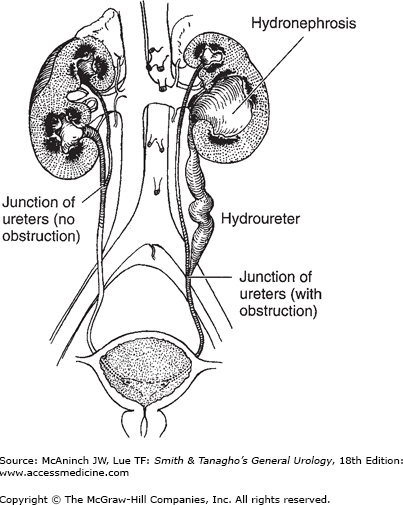

Incomplete (Y) type of duplication is caused by branching of the ureteral bud before it reaches the metanephric blastema. In most cases, this anomaly is associated with no clinical abnormality. However, disorders of peristalsis may occur near the point of union (Figure 37–1).

In complete duplication of the ureter, the presence of two ureteral buds leads to the formation of two totally separate ureters and two separate renal pelves. Because the ureter to the upper segment arises from a cephalad position on the mesonephric duct, it remains attached to the mesonephric duct longer and consequently migrates farther, ending medial and inferior to the ureter draining the lower segment (Weigert-Meyer law). Thus, the ureter draining the upper segment may migrate too far caudally and become ectopic and obstructed, whereas the ureter draining the lower segment may end laterally and have a short intravesical tunnel that leads to vesicoureteral reflux (Figure 37–2) (Tanagho, 1976). More recent studies have suggested that apoptosis of the common nephric duct cells is essential for separation of the ureter from the Wolffian duct; failure of this likely is the root cause of an ectopic ureter (Mendelsohn, 2009). Moreover, it is the urogenital sinus that induces this apoptosis and separation, and it appears that the upper ureteral bud may, in some cases, be too far from the urogenital sinus to receive the signal, thereby failing to separate from the Wolffian duct.

Although many patients with duplication of the ureter are asymptomatic, a common presentation is persistent or recurrent infections. In females, the ureter to the upper pole may be ectopic, with an opening distal to the external sphincter or even outside the urinary tract. Such patients have classic symptoms: incontinence characterized by constant dribbling and at the same time, a normal pattern of voiding. In males, because the mesonephric duct becomes the vas and seminal vesicles, the ectopic ureter is always proximal to the external sphincter, and associated incontinence does not occur. In recent years, prenatal ultrasonography has led to the diagnosis in many asymptomatic neonates.

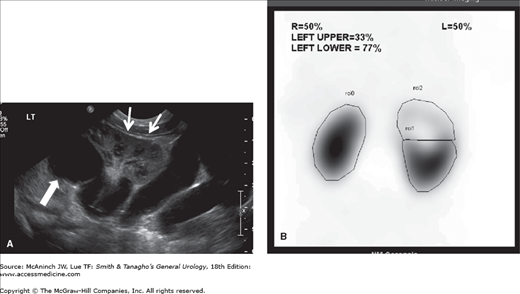

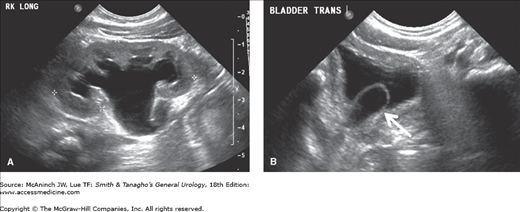

At the present time, ultrasound is the study of choice in these children. Generally, a hydronephrotic upper pole and a dilated distal ureter are seen, and in addition, one can readily evaluate parenchymal thickness and the presence of a ureterocele or other bladder anomalies. A voiding cystourethrogram is important to determine the presence of vesicoureteral reflux and confirm the presence of a ureterocele. Renal scanning (especially with 99mTc-dimercaptosuccinic acid) is helpful for estimating the degree of renal function in each renal segment (Figure 37–3).

Figure 37–3.

Duplicated left kidney. A: Ultrasound showing marked hydronephrosis of the left upper pole (large arrow) in continuity with a large tortuous ureter. The lower pole of the kidney is well preserved (small arrows). B: 99mTc-DMSA scan showing the relative function of the different renal segments.

The treatment of reflux is controversial (Chapter XXXX), but the treatment should not be influenced by the presence of ureteral duplication. Lower grades of reflux are generally treated medically and higher grades of reflux are more likely to be treated surgically. Because of anatomic variations, many surgical options are available. If upper-pole obstruction or ectopy is present, surgery is almost always required. Numerous operative approaches have been recommended (Belman et al, 1974). If renal function in one segment is very poor, heminephrectomy is the most appropriate procedure. In an effort to preserve renal parenchyma, treatments by pyeloureterostomy, ureteroureterostomy, and ureteral reimplantation are all appropriate (Amar, 1970, 1978). This can be done laparoscopically or open (Lowe et al, 2008; Prieto et al, 2009).

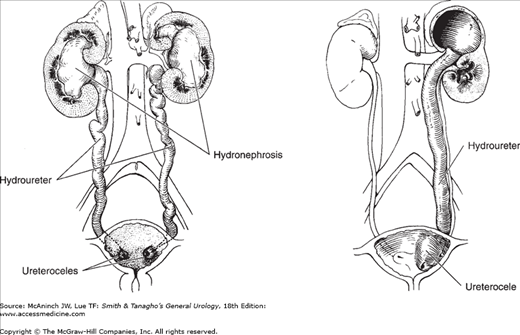

A ureterocele is a sacculation of the terminal portion of the ureter (Figure 37–4). It may be either intravesical or ectopic; in the latter case, some portion is located at the bladder neck or in the urethra. Intravesical ureteroceles are associated most often with single ureters, whereas ectopic ureteroceles nearly always involve the upper pole of duplicated ureters. Ectopic ureteroceles are four times more common than those that are intravesical (Snyder and Johnston, 1978). Ureterocele occurs seven times more often in girls than in boys, and about 10% of cases are bilateral. Mild forms of ureterocele are found occasionally in adults examined for unrelated reasons.

Ureterocele has been attributed to delayed or incomplete canalization of the ureteral bud leading to an early prenatal obstruction and expansion of the ureteral bud prior to its absorption into the urogenital sinus (Tanagho, 1976). The cystic dilation forms between the superficial and deep muscle layers of the trigone. Large ureteroceles may displace the other orifices, interfere with the muscular backing of the bladder, or even obstruct the bladder outlet. There is nearly always significant hydroureteronephrosis, and a dysplastic segment of the upper pole of the kidney may be found in association with a ureterocele.

Clinical findings vary considerably. In the past, patients presented with infection, bladder outlet obstruction, or incontinence (and rarely a ureterocele may prolapse through the female urethra). However, most of the current cases are diagnosed by antenatal maternal ultrasound. After birth, sonography and voiding cystourethrography should be performed. The former confirms the diagnosis and defines the renal anatomy and the latter demonstrates whether there is reflux into the lower pole or contralateral ureter (Figures 37–5 and 37–6). Renal scanning is helpful for estimating renal function and the combination of findings is critical in planning therapy.

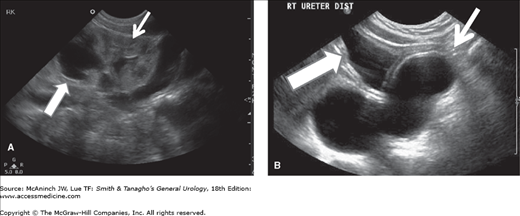

Figure 37–5.

Ureterocele in a girl with a duplication. A: Ultrasound showing marked hydronephrosis of the right upper pole (large arrow). The lower pole of the kidney is well preserved (small arrow). B: In contrast to an ectopic ureter, the dilated distal right ureter ends in a large ureterocele (small arrow) within the bladder (large arrow).

Treatment must be individualized. Transurethral incision has been recognized as the definitive procedure in many instances, particularly in patients with intravesical ureteroceles and may be the initial therapy in neonates. When an open operation is needed, the procedure must be chosen on the basis of the anatomic location of the ureteral meatus, the position of the ureterocele, and the degree of hydroureteronephrosis and impairment of renal function. In general, choices range from heminephrectomy and ureterectomy to excision of the ureterocele, vesical reconstruction, and ureteral reimplantation. When the ureterocele is ectopic, definitive treatment often entails excision of the ureterocele and reconstruction (Wang, 2008). Often, more than one procedure is necessary.

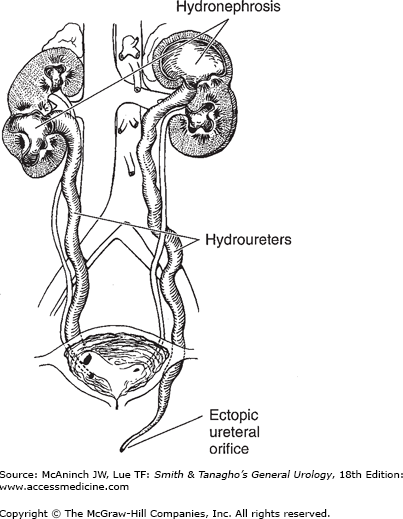

Although an ectopic ureteral orifice most commonly occurs in association with duplication of the ureter (see preceding sections), single ectopic ureters do occur. They are caused by a delay or failure of separation of the ureteral bud from the mesonephric duct during embryologic development. Again, the genetic determinants of these ureteral bud abnormalities are currently being determined, but at least GDNF signaling via the RET receptor is needed and apoptosis of the common nephric duct is critical (Michos et al, 2010). In anatomic terms, the primary anomaly may be an abnormally located ureteral bud; that also explains the high incidence of dysplastic kidneys associated with single ectopic ureters.

The clinical picture varies according to the sex of the patient and the position of the ureteral opening. Boys are seen because of urinary tract infection or epididymitis. In these cases, the ureter may drain directly into the vas deferens or seminal vesicle. In girls, the ureteral orifice may be in the urethra, vagina, or perineum. Although infection may be present, incontinence is the rule. Continual dribbling despite normal voiding is pathognomonic, but urgency and urge incontinence may confound the diagnosis.

Sonography and voiding cystourethrography help delineate the problem. If the ureter is ectopic to the urethra, the ectopic ureter may be seen on the voiding film from the voiding cystourethrography (Figure 37–7). However, because an ectopic kidney may be both tiny and in an abnormal location, it may be difficult to find by ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging, cystoscopy, or laparoscopy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis (Lipson et al, 2008). During cystoscopy, a hemitrigone may be seen and the ectopic orifice may be visualized directly or demonstrated by retrograde catheterization. Renal scanning is also helpful in estimating relative renal function. As in ureteroceles and duplication of the ureter, the clinical picture and the degree of renal function dictate the therapeutic approach.

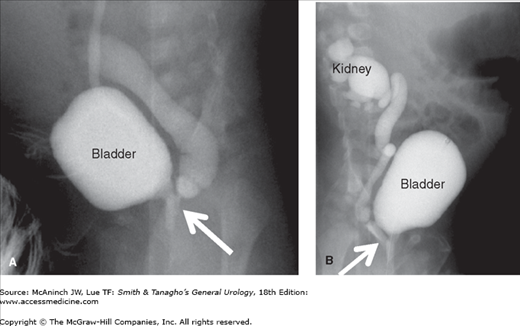

Figure 37–7.

Ectopic ureter. A: Voiding cystourethrogram in a boy showing voiding into the posterior urethra with reflux into a very dilated ureter, seen entering the prostatic urethra (arrow). B: A voiding cystourethrogram in a girl showing voiding with reflux into a very dilated ureter and continuing all the way up to a dilated lower pole of the right kidney. Note that the ureter is ectopic, entering the proximal urethra (arrow).

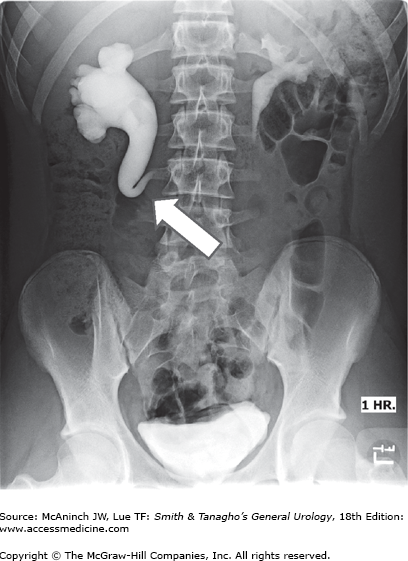

Retrocaval ureter (also called circumcaval ureter and postcaval ureter) is a rare condition in which an embryologically normal ureter becomes entrapped behind the vena cava because of abnormal persistence of the right subcardinal (as opposed to the supracardinal) vein. This forces the right ureter to encircle the vena cava from behind. The ureter descends normally to approximately the level of L3, where it curves back upward in the shape of a reverse J to pass behind and around the vena cava (Figure 37–8). Obstruction generally results.

The diagnosis of retrocaval ureter is still made by excretory urography in some cases. However, since sonography is now usually the first test performed, the radiologist must be suspicious of the anomaly based on a dilated proximal (but not distal) ureter. Currently, magnetic resonance imaging may be the best single study to delineate the anatomy clearly and noninvasively. Surgical repair for retrocaval ureter, when indicated, consists of dividing the ureter (preferably across the dilated portion), bringing the distal ureter from behind the vena cava, and reanastomosing it to the proximal end. The procedure has been performed laparoscopically to reduce morbidity (Bagheri, 2009).

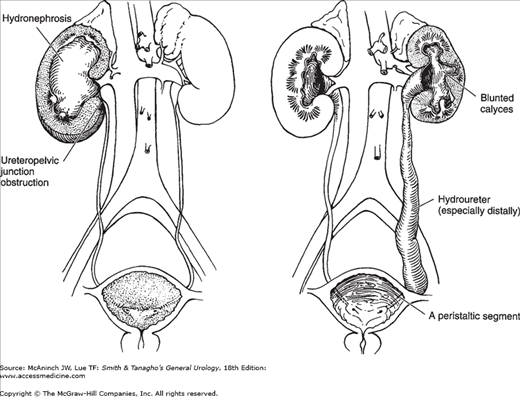

In children, primary obstruction of the ureter usually occurs at the ureteropelvic junction or the ureterovesical junction (Figure 37–9). Obstruction of the ureteropelvic junction is probably the most common congenital abnormality of the ureter. In children, it is seen more often in boys than in girls (5:2 ratio), but it has recently been discovered that in adults, it is more common in women than in men (Capello, 2005). In unilateral cases, it is more often on the left than on the right side (5:2 ratio). Bilateral obstruction occurs in 10–15% of cases and is especially common in infants (Johnston et al, 1977). The abnormality may occur in several members of the same family, but it shows no clear genetic pattern.

The exact cause of obstruction of the ureteropelvic junction often is not clear. Ureteral polyps and valves are seen but are rare. There is almost always an angulation and kink at the junction of the dilated renal pelvis and ureter. This by itself can cause obstruction, but it is unclear whether this is primary or merely secondary to another obstructive lesion. True stenosis is found rarely; however, a thin-walled, hypoplastic proximal ureter is observed frequently. Characteristic histologic and ultrastructural changes are observed in this area and could account for abnormal peristalsis through the ureteropelvic junction and consequent interference with pelvic emptying (Hanna et al, 1976). Current basic research suggests that decreased BMP4 signaling leads to disruption of smooth muscle investment of the ureter and may be involved (Wang, 2009). In addition, there seems to be an overexpression of extracellular matrix and depleted numbers of nerves (Kaya et al, 2010). Two other findings sometimes seen at operation are a high origin of the ureter from the renal pelvis and an abnormal relationship of the proximal ureter to a lower-pole renal artery. It is debatable whether these findings are the cause or the result of pelvic dilatation, but Stephens (1982)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree