Congenital Anomalies of the Penis

Congenital absence of the penis (apenia) is extremely rare. In this condition, the urethra generally opens on the perineum or inside the rectum.

Patients with apenia should be considered for assignment to the female gender. Castration and vaginoplasty should be considered in combination with estrogen treatment as the child develops.

The penis enlarges rapidly in childhood (megalopenis) in boys with abnormalities that increases the production of testosterone, for example, interstitial cell tumors of the testicle, hyperplasia, or tumors of the adrenal cortex. Management is by correction of the underlying endocrine problem.

Micropenis is a more common anomaly and has been attributed to a testosterone deficiency that results in poor growth of organs that are targets of this hormone. A penis smaller than 2 standard deviations from the norm is considered a micropenis (see Table 41–1). The testicles are small and frequently undescended. Other organs, including the scrotum, may be involved. Early evidence suggests that the ability of the hypothalamus to secrete luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) is decreased. The pituitary–gonadal axis appears to be intact, since the organs respond to testosterone, although this response may be sluggish at times. Studies have shown that topical application of 5% testosterone cream causes increased penile growth, but its effect is due to absorption of the hormone, which systemically stimulates genital growth. Patients with micropenis must be carefully evaluated for other endocrine and central nervous system anomalies. Retarded bone growth, anosmia, learning disabilities, and deficiencies of adrenocorticotropic hormone and thyrotropin have been associated with micropenis. In addition, the possibility of intersex problems must be carefully investigated before therapy is begun.

Age (years) | Length of penis (cm ± SD) | Diameter of testis (cm ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

0.2–2 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

2.1–4 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

4.1–6 | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.6 |

6.1–8 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

8.1–10 | 4.9 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.5 |

10.1–12 | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 2.7 ± 0.7 |

12.1–14 | 6.2 ± 2 | 3.4 ± 0.8 |

14.1–16 | 8.6 ± 2.4 | 4.1 ± 1 |

16.1–18 | 9.9 ± 1.7 | 5 ± 0.5 |

18.1–20 | 11 ± 1.1 | 5 ± 0.3 |

20.1–25 | 12.4 ± 1.6 | 5.2 ± 0.6 |

The approach to management of micropenis has undergone gradual change in recent years, but androgen replacement is the basic requirement. The objective is to provide sufficient testosterone to stimulate penile growth without altering growth and closure of the epiphyses. A regimen of 25 mg orally every 3 weeks for no more than four doses has been recommended. Penile growth is assessed by measuring the length of the stretched penis (pubis to glans) before and after treatment. Therapy should be started by age 1 year and aimed at maintaining genital growth commensurate with general body growth. Repeat courses of therapy may be required if the size of the penis falls behind as the child grows. For undescended testicles, orchiopexy should be done before the child is 2 years old. In the future, treatment with LHRH may correct micropenis as well as cause descent of the testicles, but at present, LHRH is not approved for such use.

In recent years, penile augmentation and enhancement procedures have been done with increasing frequency, although no validation of success has been documented. Suspensory ligament release with pubic fat pad advancement, fat injections, and dermal fat grafts have been used in attempts to enhance penile size. Many consider that these procedures have not been proved safe or efficacious in normal men. Wessells et al (1996) evaluated penile size in the flaccid and erect state in otherwise normal adult men and found very good correlation between stretched and erect length (R2= 0.793; Table 41–2). This information can provide a guideline for physicians whose patients are concerned with their penile dimensions.

Congenital Anomalies of the Urethra

Duplication of the urethra is rare. The structures may be complete or incomplete. Resection of all but one complete urethra is recommended.

Congenital urethral stricture is uncommon in infant boys. The fossa navicularis and membranous urethra are the two most common sites. Severe strictures may cause bladder damage and hydronephrosis (see Chapter 11), with symptoms of obstruction (urinary frequency and urgency) or urinary infection. A careful history and physical examination are indicated in patients with these complaints. Excretory urography and excretory voiding urethrography often define the lesion and the extent of obstruction. Retrograde urethrography (Figure 41–1) may also be helpful. Cystoscopy and urethroscopy should be performed in all patients in whom urethral stricture is suspected.

Figure 41–1.

Upper left: Retrograde urethrogram showing congenital diaphragmatic stricture. Upper right: Posterior urethral valves revealed on voiding cystourethrography. Arrow points to area of severe stenosis at distal end of prostatic urethra. Lower left: Posterior urethral valves. Patient would not void with cystography. Retrograde urethrogram showing valves (arrow). Lower right: Cystogram, same patient. Free vesicoureteral reflux and vesical trabeculation with diverticula.

Strictures can be treated at the time of endoscopy. Diaphragmatic strictures may respond to dilation or visual urethrotomy. Other strictures should be treated under direct vision by internal urethrotomy with the currently available pediatric urethrotome. It may be necessary to repeat these procedures in order to stabilize the stricture. Single-stage open surgical repair by anastomotic urethroplasty, buccal mucosa graft, or penile flap is desirable if the obstruction recurs.

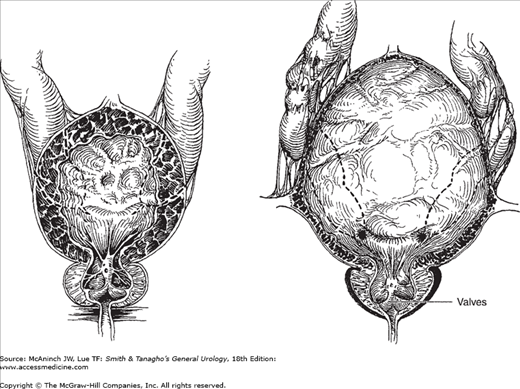

Posterior urethral valves, the most common obstructive urethral lesions in infants and newborns, occur only in males and are found at the distal prostatic urethra. The valves are mucosal folds that look like thin membranes; they may cause varying degrees of obstruction when the child attempts to void (Figure 41–2).

Figure 41–2.

Posterior urethral valves. Left: Dilatation of the prostatic urethra, hypertrophy of vesical wall and trigone in stage of compensation; bilateral hydroureters secondary to trigonal hypertrophy. Right: Attenuation of bladder musculature in stage of decompensation; advanced ureteral dilatation and tortuosity, usually secondary to vesicoureteral reflux.

Children with posterior urethral valves may present with mild, moderate, or severe symptoms of obstruction. They often have a poor, intermittent, dribbling urinary stream. Urinary infection and sepsis occur frequently. Severe obstruction may cause hydronephrosis (see Chapter 11), which is apparent as a palpable abdominal mass. A palpable midline mass in the lower abdomen is typical of a distended bladder. Occasionally, palpable flank masses indicate hydronephrotic kidneys. In many patients, failure to thrive may be the only significant symptom, and examination may reveal nothing more than evidence of chronic illness.

Azotemia and poor concentrating ability of the kidney are common findings. The urine is often infected, and anemia may be found if infection is chronic. Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels and creatinine clearance are the best indicators of the extent of renal failure.

Voiding cystourethrography is the best radiographic study available to establish the diagnosis of posterior urethral valves. The presence of large amounts of residual urine is apparent on initial catheterization done in conjunction with radiographic studies, and an uncontaminated urine specimen should be obtained via the catheter and sent for culture. The cystogram may show vesicoureteral reflux and the severe trabeculations of long-standing obstruction, and the voiding cystourethrogram often demonstrates elongation and dilatation of the posterior urethra, with a prominent bladder neck (Figure 41–1). Excretory urograms may reveal hydroureter and hydronephrosis when obstruction is severe and long standing.

Ultrasonography can be used to detect hydronephrosis, hydroureter, and bladder distention in children with severe azotemia. It can also detect fetal hydronephrosis, which is typical of urethral valves, as early as 28 weeks of gestation; when the obstruction is from valves, an enlarged bladder with bilateral hydroureteronephrosis is usually present.

Urethroscopy and cystoscopy, performed with the patient under general anesthesia, show vesical trabeculation and cellules and, occasionally, vesical diverticula. The bladder neck and trigone may be hypertrophied. The diagnosis is confirmed by visual identification of the valves at the distal prostatic urethra. Supravesical compression shows that the valves cause obstruction.

Treatment consists of destruction of the valves, but the approach depends on the degree of obstruction and the general health of the child. In children with mild to moderate obstruction and minimal azotemia, transurethral fulguration of the valves is usually successful. Occasionally, catheterization, cystoscopy, or urethral dilation by perineal urethrostomy destroys the valves.

The more severe degrees of obstruction create varying grades of hydronephrosis requiring individualized management. Treatment of children with urosepsis and azotemia associated with hydronephrosis includes use of antibiotics, catheter drainage of the bladder, and correction of the fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Vesicostomy may be of benefit in patients with reflux and renal dysplasia.

In the most severe cases of hydronephrosis, vesicostomy or removal of the valves may not be sufficient, because of ureteral atony, obstruction of the ureterovesical junction from trigonal hypertrophy, or both. In such cases, percutaneous loop ureterostomies may be done to preserve renal function and allow resolution of the hydronephrosis. After renal function is stabilized, valve ablation and reconstruction of the urinary tract can be done.

The period of proximal diversion should be as short as possible, since vesical contracture can be permanent after prolonged supravesical diversion.

It has been noted that approximately 50% of children with urethral valves have vesicoureteral reflux and that the prognosis is worse if the reflux is bilateral. After removal of the obstruction, reflux ceases spontaneously in about one-third of patients. In the remaining two-thirds of patients, the reflux should be corrected surgically.

Long-term use of antimicrobial drugs is often required to prevent recurrent urosepsis and urinary tract infection even though the obstruction has been relieved.

Early detection is the best way to preserve kidney and bladder function. This can be accomplished by ultrasonography in utero, by careful physical examination and observation of voiding in the newborn, and by thorough evaluation of children who have urinary tract infections. Children in whom azotemia and infection persist after relief of obstruction have a poor prognosis.

Signs of anterior urethral valves, a rare congenital anomaly, are urethral dilatation or diverticula proximal to the valve, bladder outlet obstruction, postvoiding incontinence, and infection. Enuresis may be present. Urethroscopy and voiding cystourethrography will demonstrate the lesion, and endoscopic electrofulguration will effectively correct the obstruction.

Urethrorectal and vesicorectal fistulas are rare and are almost always associated with imperforate anus. Failure of the urorectal septum to develop completely and separate the rectum from the urogenital tract permits communication between the two systems (see Chapter 2). The child with such a fistula passes fecal material and gas through the urethra. If the anus has developed normally (ie, if it opens externally), urine may pass through the rectum.

Cystoscopy and panendoscopy usually show the fistulous opening. Radiographic contrast material given by mouth will reach the blind rectal pouch, and the distance between the end of the rectum and the perineum can be seen on appropriate radiograms.

Imperforate anus must be opened immediately and the fistula closed, or if the rectum lies quite high, temporary sigmoid colostomy should be performed. Definitive surgery, with repair of the urethral fistula, can be done later.

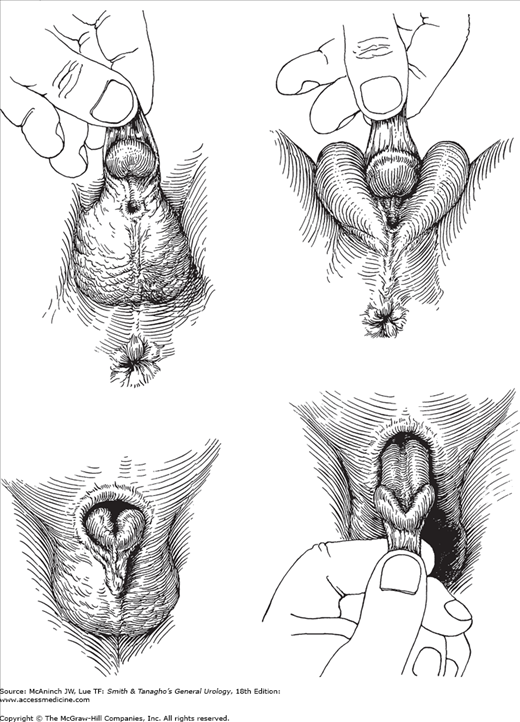

In hypospadias, the urethral meatus opens on the ventral side of the penis proximal to the tip of the glans penis (Figure 41–3).

Figure 41–3.

Hypospadias and epispadias. Upper left: Hypospadias, penoscrotal type. Redundant dorsal foreskin that is deficient ventrally; ventral chordee. Upper right: Hypospadias, midscrotal type. Chordee more marked. Penis often small. Lower left: Epispadias. Redundant ventral foreskin that is absent dorsally; severe dorsal chordee. Lower right: Traction on foreskin reveals dorsal defect.

Sexual differentiation and urethral development begin in utero at approximately 8 weeks and are complete by 15 weeks. The urethra is formed by the fusion of the urethral folds along the ventral surface of the penis, which extends to the corona on the distal shaft. The glandular urethra is formed by canalization of an ectodermal cord that has grown through the glans to communicate with the fused urethral folds (see Chapter 2). Hypospadias results when fusion of the urethral folds is incomplete.

Hypospadias occurs in 1 in every 300 male children. Estrogens and progestins given during pregnancy are known to increase the incidence. Although a familial pattern of hypospadias has been recognized, no specific genetic traits have been established.

There are several forms of hypospadias classified according to location: (1) glandular, that is, opening on the proximal glans penis; (2) coronal, that is, opening at the coronal sulcus; (3) penile shaft; (4) penoscrotal; and (5) perineal. About 70% of all cases of hypospadias are distal penile or coronal.

Hypospadias in the male is evidence of feminization. Patients with penoscrotal and perineal openings should be considered to have potential intersex problems requiring appropriate evaluation. Hypospadiac newborns should not be circumcised, because the preputial skin may be useful for future reconstruction.

Although newborns and young children seldom have symptoms related to hypospadias, older children and adults may complain of difficulty directing the urinary stream and stream spraying. Chordee (curvature of the penis) causes ventral bending and bowing of the penile shaft, which can prevent sexual intercourse. Perineal or penoscrotal hypospadias necessitates voiding in the sitting position, and these proximal forms of hypospadias in adults can be the cause of infertility. An additional complaint of almost all patients is the abnormal (hooded) appearance of the penis, caused by deficient or absent ventral foreskin. The hypospadiac meatus may be stenotic and should be carefully examined and calibrated. (A meatotomy should be done when stenosis exists.) There is an increased incidence of undescended testicles in children with hypospadias; scrotal examination is necessary to establish the position of the testicles.

Since children with penoscrotal and perineal hypospadias often have a bifid scrotum and ambiguous genitalia, a buccal smear and karyotyping are indicated to help establish the genetic sex. Urethroscopy and cystoscopy are of value to determine whether internal male sexual organs are normally developed. Excretory urography is also indicated in these patients to detect additional congenital anomalies of the kidneys and ureters.

Some authors recommend routine use of excretory urography for all patients with hypospadias; however, this seems to be of little value in the more distal types of the disorder, because there appears to be no increased incidence of upper urinary tract anomalies.

Any degree of hypospadias is an expression of feminization. Perineal and scrotal urethral openings should be carefully evaluated to ascertain that the patient is not a female with androgenized adrenogenital syndrome. Urethroscopy and cystoscopy will aid in evaluating the development of internal reproductive organs.

For psychological reasons, hypospadias should be repaired before the patient reaches school age; in most cases, this can be done before age 2.

More than 150 methods of corrective surgery for hypospadias have been described. Currently, one-stage repairs with foreskin island flaps and incised urethral plate are performed by many urologists. It now appears that buccal mucosa grafts are more advantageous than others and should be considered the primary grafting technique when indicated. Fistulas occur in 15–30% of patients, but the fistula repair is considered a small, second-stage reconstruction.

All types of repair involve straightening the penis by removal of the chordee. The chordee removal can be confirmed by producing an artificial erection in the operating room following urethral reconstruction and advancement. Most successful techniques for repair of hypospadias use local skin and foreskin in developing the neourethra. In recent years, advancement of the urethra to the glans penis has become technically feasible and cosmetically acceptable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree