Congenital Anomalies of the Kidneys

Congenital anomalies occur more frequently in the kidney than in any other organ. Some cause no difficulty, but many (eg, hypoplasia, polycystic kidneys) cause impairment of renal function. It has been noted that children with a gross deformity of an external ear associated with ipsilateral maldevelopment of the facial bones are apt to have a congenital abnormality of the kidney (eg, ectopy, hypoplasia) on the same side as the visible deformity. Lateral displacement of the nipples has been observed in association with bilateral renal hypoplasia.

A significant incidence of renal agenesis, ectopy, malrotation, and duplication has been observed in association with congenital scoliosis and kyphosis. Unilateral agenesis, hypoplasia, and dysplasia are often seen in association with supralevator imperforate anus. For a better understanding of these congenital abnormalities, see the discussion of the embryology and development of the kidney in Chapter 2.

Agenesis

Bilateral renal agenesis is extremely rare; no more than 400 cases have been reported. The children do not survive. The condition does not appear to have any predisposing factors. Prenatal suspicion of the anomaly exists when oligohydramnios is present on fetal ultrasound examination. Pulmonary hypoplasia and facial deformities (Potter facies) are usually present. Abdominal ultrasound examination usually establishes the diagnosis.

One kidney may be absent (estimated incidence: 1 in 450–1000 births). In some cases, this may be because the ureteral bud (from the Wolffian duct) failed to develop or, if it did develop, did not reach the metanephros (adult kidney). Without a drainage system, the metanephric mass undergoes atrophy. The ureter is absent on the side of the unformed kidney in 50% of cases, although a blind ureteral duct may be found (see Chapter 2).

Renal agenesis causes no symptoms; it is usually found by accident on abdominal or renal imaging. It is not an easy diagnosis to establish even though on inspection of the bladder, the ureteral ridge is absent and no orifice is visualized, for the kidney could be present but be drained by a ureter whose opening is ectopic (into the urethra, seminal vesicle, or vagina). If definitive diagnosis seems essential, isotope studies, ultrasonography, and computed tomography (CT) should establish the diagnosis.

Hypoplasia

Hypoplasia implies a small kidney. The total renal mass may be divided in an unequal manner, in which case one kidney is small and the other correspondingly larger than normal. Some of these congenitally small kidneys prove, on pathologic examination, to be dysplastic. Unilateral or bilateral hypoplasia has been observed in infants with fetal alcohol syndrome, and renal anomalies have been reported in infants with in utero cocaine exposure.

Differentiation from acquired atrophy is difficult. Atrophic pyelonephritis usually reveals typical distortion of the calyces. Vesicoureteral reflux in infants may cause a dwarfed kidney even in the absence of infection. Stenosis of the renal artery leads to shrinkage of the kidney.

Supernumerary Kidneys

Dysplasia and Multicystic Kidney

Renal dysplasia has protean manifestations. Multicystic kidney of the newborn is usually unilateral, nonhereditary, and characterized by an irregularly lobulated mass of cysts; the ureter is usually absent or atretic. It may develop because of faulty union of the nephron and the collecting system. At most, only a few embryonic glomeruli and tubules are observed. The only finding is the discovery of an irregular mass in the flank. Nothing is shown on urography, but in an occasional case, some radiopaque fluid may be noted. If the cystic kidney is large, its mate is usually normal. However, when the cystic organ is small, the contralateral kidney is apt to be abnormal. The cystic nature of the lesion may be revealed by sonography, and the diagnosis can be established in utero. If the physician feels that the proper diagnosis has been made, no treatment is necessary. If there is doubt about the diagnosis, nephrectomy is considered the procedure of choice. Neoplastic changes in multicystic renal dysplasia have been noted, but this is accepted as a benign condition.

Multicystic kidney is often associated with contralateral renal and ureteral abnormalities. Contralateral ureteropelvic junction obstruction is one of the common problems noted. Diagnostic evaluation of both kidneys is required to establish the overall status of anomalous development.

Dysplasia of the renal parenchyma is also seen in association with ureteral obstruction or reflux that was probably present early in pregnancy. It is relatively common as a segmental renal lesion involving the upper pole of a duplicated kidney whose ureter is obstructed by a congenital ureterocele. It may also be found in urinary tracts severely obstructed by posterior urethral valves; in this instance, the lesion may be bilateral.

Adult Polycystic Kidney Disease

Adult polycystic kidney disease is an autosomal dominant hereditary condition and almost always bilateral (95% of cases). The disease encountered in infants is different from that seen in adults, although the literature reports a small number of infants with the adult type. The former is an autosomal recessive disease in which life expectancy is short, whereas that diagnosed in adulthood is autosomal dominant; symptoms ordinarily do not appear until after age 40. Cysts of the liver, spleen, and pancreas may be noted in association with both forms. The kidneys are larger than normal and are studded with cysts of various sizes.

The evidence suggests that the cysts occur because of defects in the development of the collecting and uriniferous tubules and in the mechanism of their joining. Blind secretory tubules that are connected to functioning glomeruli become cystic. As the cysts enlarge, they compress adjacent parenchyma, destroy it by ischemia, and occlude normal tubules. The result is progressive functional impairment.

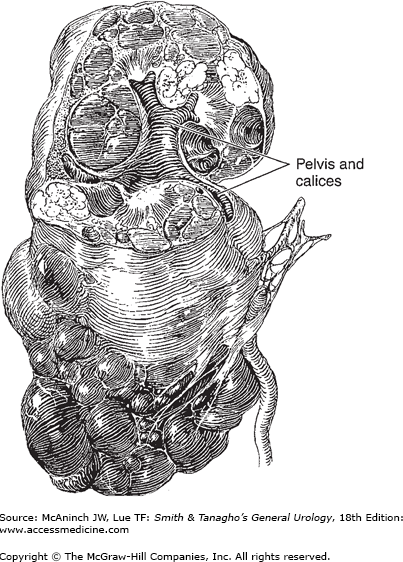

Grossly, the kidneys are usually much enlarged. Their surfaces are studded with cysts of various sizes (Figure 32–1). On section, the cysts are found to be scattered throughout the parenchyma. Calcification is rare. The fluid in the cyst is usually amber colored but may be hemorrhagic.

Microscopically, the lining of the cysts consists of a single layer of cells. The renal parenchyma may show peritubular fibrosis and evidence of secondary infection. There appears to be a reduction in the number of glomeruli, some of which may be hyalinized. Renal arteriolar thickening is a prominent finding in adults.

Pain over one or both kidneys may occur because of the drag on the vascular pedicles by the heavy kidneys, from obstruction or infection, or from hemorrhage into a cyst. Gross or microscopic total hematuria is not uncommon and may be severe; the cause for this is not clear. Colic may occur if blood clots or stones are passed. The patient may notice an abdominal mass.

Infection (chills, fever, renal pain) commonly complicates polycystic disease. Symptoms of vesical irritability may be the first complaint. When renal insufficiency ensues, headache, nausea and vomiting, weakness, and loss of weight occur.

One or both kidneys are usually palpable. They may feel nodular. If infected, they may be tender. Hypertension is found in 60–70% of these patients. Evidence of cardiac enlargement is then noted.

Fever may be present if pyelonephritis exists or if cysts have become infected. In the stage of uremia, anemia and loss of weight may be evident. Ophthalmoscopic examination may show changes typical of moderate or severe hypertension.

Anemia may be noted, caused either by chronic loss of blood or, more commonly, by the hematopoietic depression accompanying uremia. Proteinuria and microscopic (if not gross) hematuria are the rule. Pyuria and bacteriuria are common.

Progressive loss of concentrating power occurs. Renal clearance tests show varying degrees of renal impairment. About one-third of patients with polycystic kidney disease are uremic when first seen.

Both renal shadows are usually enlarged on a plain film of the abdomen, even as much as five times normal size. Kidneys >16 cm in length are suspect.

The renal masses are usually enlarged and the calyceal pattern is quite bizarre (spider deformity). The calyces are broadened and flattened, enlarged, and often curved, as they tend to hug the periphery of adjacent cysts. Often, the changes are only slight or may even be absent on one side, leading to the erroneous diagnosis of tumor of the other kidney. If cysts are infected, perinephritis may obscure the renal and even the psoas shadows.

CT is an excellent noninvasive technique used to establish the diagnosis of polycystic disease. The multiple thin-walled cysts filled with fluid and the large renal size make this imaging method extremely accurate (95%) for diagnosis.

Photoscans reveal multiple “cold” avascular spots in large renal shadows.

Sonography appears to be superior to both excretory urography and isotope scanning in diagnosis of polycystic disorders.

Cystoscopy may show evidence of cystitis, in which case the urine will contain abnormal elements. Bleeding from a ureteral orifice may be noted. Ureteral catheterization and retrograde urograms are rarely indicated.

Bilateral hydronephrosis (on the basis of congenital or acquired ureteral obstruction) may present bilateral flank masses and signs of impairment of renal function, but ultrasonography shows changes quite different from those of the polycystic kidney.

Bilateral renal tumor is rare but may mimic polycystic kidney disease perfectly on urography. Tumors are usually localized to one portion of the kidney, whereas cysts are quite diffusely distributed. The total renal function should be normal with unilateral tumor but is usually depressed in patients with polycystic kidney disease. CT scan may be needed at times to differentiate between the two conditions.

In von Hippel-Lindau disease (angiomatous cerebellar cyst, angiomatosis of the retina, and tumors or cysts of the pancreas), multiple bilateral cysts or adenocarcinomas of both kidneys may develop. The presence of other stigmas should make the diagnosis. CT, angiography, sonography, or scintiphotography should be definitive.

Tuberous sclerosis (convulsive seizures, mental retardation, and adenoma sebaceum) is typified by hamartomatous tumors often involving the skin, brain, retinas, bones, liver, heart, and kidneys (see Chapter 21). The renal lesions are usually multiple and bilateral and microscopically are angiomyolipomas. The presence of other stigmas and use of CT or sonography should make the differentiation.

A simple cyst (see section following) is usually unilateral and single; total renal function should be normal. Urograms usually show a single lesion (Figure 32–2), whereas polycystic kidney disease is bilateral and has multiple filling defects.

Figure 32–2.

Simple cyst. Upper left: Large cyst displacing lower pole laterally. Upper right: Section of kidney showing one large and a few small cysts. Lower left: Excretory urogram showing soft-tissue mass in upper pole of right kidney. Elongation and distortion of upper calyces by cyst. Lower right: Infusion nephrotomogram showing large cyst in upper renal pole distorting upper calyces and dislocating upper portion of kidney laterally.

For reasons that are not clear, pyelonephritis is a common complication of polycystic kidney disease. It may be asymptomatic; pus cells in the urine may be few or absent. Stained smears or quantitative cultures make the diagnosis. A gallium-67 citrate scan will definitely reveal the sites of infection, including abscess.

Infection of cysts is associated with pain and tenderness over the kidney and a febrile response. The differential diagnosis between infection of cysts and pyelonephritis may be difficult, but here again a gallium scan will prove helpful. In rare instances, gross hematuria may be so brisk and persistent as to endanger life.

Except for unusual complications, the treatment is conservative and supportive.

The patient should be put on a low-protein diet (0.5–0.75 g/kg/day of protein) and fluids forced to 3000 mL or more per day. Physical activity may be permitted within reason, but strenuous exercise is contraindicated. When the patient is in the state of absolute renal insufficiency, one should treat as for uremia from any cause. Hypertension should be controlled. Hemodialysis may be indicated.

There is no evidence that excision or decompression of cysts improves renal function. If a large cyst is found to be compressing the upper ureter, causing obstruction and further embarrassing renal function, it should be resected or aspirated. When the degree of renal insufficiency becomes life threatening, chronic dialysis or renal transplantation should be considered.

Pyelonephritis must be rigorously treated to prevent further renal damage. Infection of cysts requires surgical drainage. If bleeding from one kidney is so severe that exsanguination is possible, nephrectomy or embolization of the renal or, preferably, the segmental artery must be considered as a life-saving measure. Concomitant diseases (eg, tumor, obstructing stone) may require definitive surgical treatment.

When the disease affects children, it has a very poor prognosis. The large group presenting clinical signs and symptoms after age 35–40 has a somewhat more favorable prognosis. Although there is wide variation, these patients usually do not live longer than 5 or 10 years after the diagnosis is made, unless dialysis is made available or renal transplantation is done.

Simple (Solitary) Cyst

Simple cyst (Figures 32–2 and 32–3) of the kidney is usually unilateral and single but may be multiple and multilocular and, more rarely, bilateral. It differs from polycystic kidneys both clinically and pathologically.

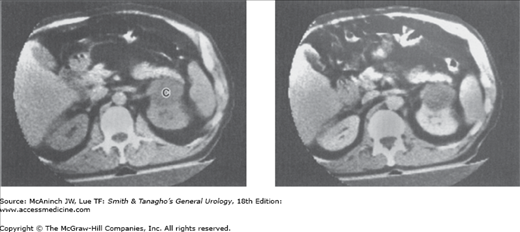

Figure 32–3.

Left renal cyst. Left: Computed tomography (CT) scan shows a homogeneous low-density mass (C) arising from anterior border of left kidney just posterior to tail of the pancreas. The CT attenuation value was similar to that of water, indicating a simple renal cyst. Right: After intravenous injection of contrast material, the mass did not increase in attenuation value, adding further confirmatory evidence of its benign cystic nature.

Whether simple cyst is congenital or acquired is not clear. Its origin may be similar to that of polycystic kidneys, that is, the difference may be merely one of degree. On the other hand, simple cysts have been produced in animals by causing tubular obstruction and local ischemia; this suggests that the lesion can be acquired.

As a simple cyst grows, it compresses and thereby may destroy renal parenchyma, but rarely does it destroy so much renal tissue that renal function is impaired. A solitary cyst may be placed in such a position as to compress the ureter, causing progressive hydronephrosis. Infection may complicate the picture.

Acquired cystic disease of the kidney can arise as an effect of chronic dialysis. The spontaneous regression of cysts has occasionally been noted.

Simple cysts usually involve the lower pole of the kidney. Those that produce symptoms average about 10 cm in diameter, but a few are large enough to fill the entire flank. They usually contain a clear amber fluid. Their walls are quite thin, and the cysts are “blue-domed” in appearance. Calcification of the sac is occasionally seen. About 5% contain hemorrhagic fluid, and possibly one-half of these have papillary cancers on their walls.

Simple cysts are usually superficial but may be deeply situated. When a cyst is situated deep in the kidney, the cyst wall is adjacent to the epithelial lining of the pelvis or calyces, from which it may be separated only with great difficulty. Cysts do not communicate with the renal pelvis (Figure 32–2). Microscopic examination of the cyst wall shows heavy fibrosis and hyalinization; areas of calcification may be seen. The adjacent renal tissue is compressed and fibrosed. A number of cases of simple cysts have been reported in children. However, large cysts are rare in children; the presence of cancer must therefore be ruled out.

Multilocular renal cysts may be confused with tumor on urography. Sonography usually makes the diagnosis. Occasionally, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be necessary.

The Bosniak classification of simple renal cysts is an aid to determining the chance of malignancy based on imaging criteria. Type I cysts are simple and smooth walled, with clear fluid; Type II cysts are also benign, but may have minimal septations and a small fine rim of calcification; Type III cysts are more complex, with more calcification, increasing septations, and a thick cyst wall; Type IV cysts have a thickened irregular wall, often with calcifications, and a mass may be noted inside the cyst, suggesting carcinoma. Numerous variations of the findings are used as a guide in the diagnosis of renal cancer.

Pain in the flank or back, usually intermittent and dull, is not uncommon. If bleeding suddenly distends the cyst wall, pain may come on abruptly and be severe. Gastrointestinal symptoms are occasionally noted and may suggest peptic ulcer or gallbladder disease. The patient may discover a mass in the abdomen, although cysts of this size are unusual. If the cyst becomes infected, the patient usually complains of pain in the flank, malaise, and fever.

Physical examination is usually normal, although occasionally a mass in the region of the kidney may be palpated or percussed. Tenderness in the flank may be noted if the cyst becomes infected.

Urinalysis is usually normal. Microscopic hematuria is rare. Renal function tests are normal unless the cysts are multiple and bilateral (rare). Even in the face of extensive destruction of one kidney, compensatory hypertrophy of the other kidney will maintain normal total function.

CT scan appears to be the most accurate means of differentiating renal cyst and tumor (Figure 32–3). Cysts have an attenuation approximating that of water, whereas the density of tumors is similar to that of normal parenchyma. Parenchyma is made more dense with the intravenous injection of radiopaque fluid, but a cyst remains unaffected. The wall of a cyst is sharply demarcated from the renal parenchyma; a tumor is not. The wall of a cyst is thin, and that of a tumor is not. CT scan may well supplant cyst puncture in the differentiation of cyst and tumor in many cases.

Renal ultrasonography is a noninvasive diagnostic technique that in a high percentage of cases differentiates between a cyst and a solid mass. If findings on ultrasonography are also compatible with a cyst, a needle can be introduced into the cyst under ultrasonographic control and the cyst can be aspirated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree