Congenital Anomalies of the Bladder

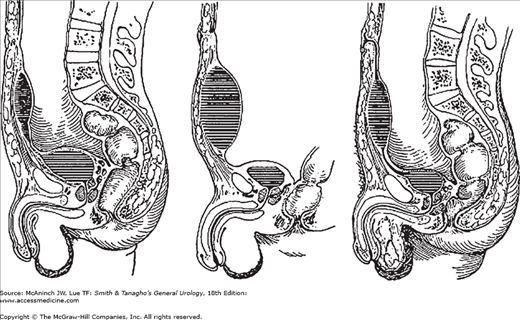

Exstrophy of the bladder is a rare congenital anomaly with complete ventral defect of the urogenital sinus and the overlying skeletal system (Gambhir et al, 2008). Incidence of this anomaly is reported to be 3.3 per 100,000 births. Male to female ratio is about 1.5:1 (Anon, 1987).

The lower central abdomen is occupied by the inner surface of the posterior wall of the bladder, whose mucosal edges are fused with the skin. Urine spurts onto the abdominal wall from the ureteral orifices.

The rami of the pubic bones are widely separated. The pelvic ring thus lacks rigidity, the femurs are rotated externally, and the child “waddles like a duck.”

The rectus muscles are widely separated from each other caudally. A hernia, made up of the exstrophic bladder and surrounding skin, is present.

Epispadias is almost always associated. Undescended testicles may be seen, and the anus and vagina located anteriorly. Urinary tract infection and hydronephrosis are common.

Prenatal diagnosis is difficult (Austin et al, 1998; Emanuel et al, 1995). Obvious anomaly of exposed bladder mucosa makes diagnosis easy at birth. X-ray studies will reveal separation of pubic bones.

Historical treatment includes staged repair of this anomaly (Stec et al, 2011). The first stage is to close the abdominal wall, the bladder, and the posterior urethra. Orthopedic procedure of sacral osteotomy in order to close the abdominal wall may be necessary (Meldrum et al, 2003; Suson et al, 2011; Vining et al, 2011). Mollard (1980) recommends the following steps for satisfactory repair of bladder exstrophy (Mollard, 1980): (1) bladder closure with sacral osteotomy in order to close the pelvic ring at the pubic symphysis (Cervellione, 2011), plus lengthening of the penis; (2) antiureteral reflux procedure and bladder neck reconstruction; and (3) repair of the epispadiac penis. Treatment needs to be initiated prior to the fibrosis of the bladder mucosa in order to repair this anomaly completely (Oesterling and Jeffs, 1987). When the bladder is small, fibrotic, and inelastic, functional closure becomes inadvisable, and urinary diversion with cystectomy is the treatment of choice. Modern approach is to perform primary repair of this anomaly completely (Mitchell, 2005; Mourtzinos and Borer, 2004). Recent studies show better outcomes with primary repair (Grady et al, 1999; Kiddoo et al, 2004; Lowentritt et al, 2005).

Common complications after surgical repair include incontinence (Gargollo et al, 2011; Light and Scott, 1983; Perlmutter et al, 1991; Toguri et al, 1978), infertility, vesicoureteral reflux, and urinary tract infection (Ebert et al, 2008; Gargollo and Borer, 2007). Complete primary closure appears to be the best choice for improved continence. Adenocarcinoma of the bladder and rectum are noted in higher frequency (Husmann and Rathbun, 2008).

Embryologically, the allantois connects the urogenital sinus with the umbilicus. Normally, the allantois is obliterated and is represented by a fibrous cord (urachus) extending from the dome of the bladder to the navel (Bauer and Retik, 1978). Urachal formation is directly related to bladder descent. Lack of descent is more commonly associated with patent urachus than with bladder outlet obstruction (Scheye et al, 1994).

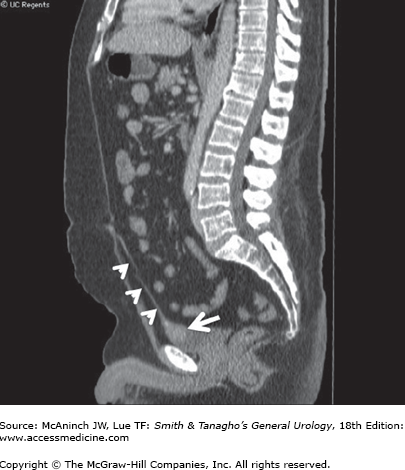

If the urachal obliteration is complete except at the superior end, a draining umbilical sinus may be noted. If it becomes infected, the drainage will be purulent. If the inferior end remains open, it will communicate with the bladder, but this does not usually produce symptoms. Rarely, the entire tract remains patent, in which case urine drains constantly from the umbilicus. This is apt to become obvious within a few days of birth. If only the ends of the urachus seal off, a cyst of that body may form and may become quite large, presenting a low midline mass (Figure 38–1) (al-Hindawi and Aman, 1992). If the cyst becomes infected, signs of general and local sepsis will develop (Mesrobian et al, 1997).

Adenocarcinoma may occur in an urachal cyst, particularly at its vesical extremity (Figure 38–2), and tends to invade the tissues beneath the anterior abdominal wall.

Physical examination reveals opening sinus or lower abdominal mass. Computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or ultrasound may show cystic structure adjacent to the bladder dome (Chouhan et al, 2011; Cilento et al, 1998; Holten et al, 1996). Cystoscope may show extrinsic compression from the mass. Stones may develop in a cyst of the urachus and can be identified on a plain x-ray film.

Treatment consists of excision of the urachus, which lies on the peritoneal surface (Chan et al, 2009; Destri et al, 2011; Stone et al, 1995; Yohannes et al, 2003). If adenocarcinoma is present, radical resection is required. Unless other serious congenital anomalies are present, the prognosis is good (Upadhyay and Kukkady, 2003). The complication of adenocarcinoma offers a poor prognosis (Gopalan et al, 2009).

Congenital diverticulum is found in approximately 1.7% of children (Blane et al, 1994). This is caused by the congenital weakness of Waldeyer fascial sheath. Most of the cases are asymptomatic; however, it can cause urinary tract infection, and in rare cases, it can cause ureteral or bladder outlet obstruction (Bhat et al, 2011; Bogdanos et al, 2005; Pieretti and Pieretti-Vanmarcke, 1999).

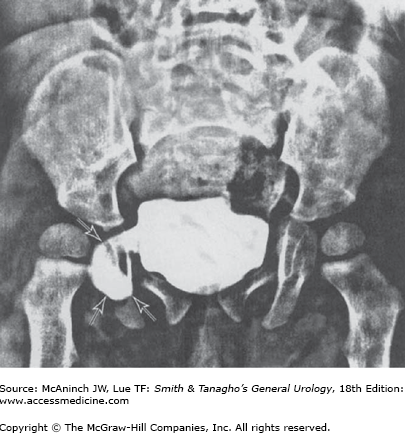

One side of the bladder may become involved in an inguinal hernia (Figure 38–3). Such a mass may recede on urination. The condition can be found during contrast x-ray studies of urinary tract (Bjurlin et al, 2011; Catalano, 1997). However, it is more commonly found as a previously unsuspected complication during surgical correction of a hernia (McCormack et al, 2005; Patle et al, 2011).

Megacystis is a condition with enlarged bladder due to overdistention during the development, commonly associated with massive reflux with hydronephrosis (Burbige et al, 1984). This condition can be associated with other conditions, such as posterior valve (Confer et al, 2011), Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (Sato et al, 1993), and meningomyelocele (Blane et al, 1994).

Acquired Diseases of the Bladder

Interstitial cystitis is unknown etiology syndrome characterized by urinary frequency, urgency, and bladder pain (Nickel, 2004). In the past, it was reported to be frequently affecting middle-aged women; however, recent studies revealed that it affect men and women in all ages (Kusek and Nyberg, 2001). Recent study showed that as high as 12% of women may be affected with early symptoms of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) (Rosenberg and Hazzard, 2005).

Common symptoms with IC/BPS are bladder pain worsened with bladder filling, certain food intake, and burning on urination. Urinary frequency, nocturia, and urgency are also common.

The etiology of IC/BPS is unknown and various causes are proposed. These include increased mast cell in the bladder wall, deficiency of glycosaminoglycan layer over bladder mucosa leading to bladder wall inflammation by urine stimulation, unknown virus infection, toxic substance in the urine, autoimmune disorder, etc (Buffington, 2004; Burkman, 2004; Clemens et al, 2008; Elbadawi, 1997; Wesselmann, 2001).

Laboratory test: The urine is almost always free of infection. Microscopic hematuria may be noted. Results of renal function tests are normal except in the occasional patient in whom vesical fibrosis has led to vesicoureteral reflux or obstruction. No urine cytology or markers are found to be specific to IC/BPS (Hurst et al, 1993). No serologic tests are shown to be diagnostic for this condition.

Imaging: No radiographic findings are found to be specific to IC/BPS. Excretory urograms are usually normal unless reflux has occurred, in which case hydronephrosis is found. The accompanying cystogram reveals a bladder of small capacity; reflux into a dilated upper tract may be noted on cystography.

Urodynamic study: Urodynamic study is not required for diagnosis of IC/BPS; however, it can be used to rule out other condition, such as neurogenic bladder or bladder outlet obstruction.

Cystoscopy: Diagnostic cystoscopy is commonly performed under anesthesia in order to adequately distend the bladder. Typical cystoscopic findings associated with IC/BPS are reduced capacity, scarring and cracking of the mucosa with distention (Hunner’s ulcer), and appearance of glomerulation (diffuse petechial hemorrhages in the mucosa) after distension. However, classic Hunner’s ulcer is rare. Glomerulation can be seen with other conditions, and the finding is not specific to IC/BPS (Ottem and Teichman, 2005; Simon et al, 1997).

Histology: Bladder biopsy has been shown to have increase mast cell in the bladder wall (Sant and Theoharides, 1994). However, this finding does not include or exclude the diagnosis (Johansson and Fall, 1990).

KCl test: Patients with deficiency of the urothelial defense layer (Nickel et al, 1993) may experience severe pain with instillation of potassium chloride solution in the bladder. However, this test is controversial and not widely used.

Validated questionnaires: The Wisconsin Interstitial Cystitis Scale and The Interstitial Cystitis symptom and Problem Index (O’Leary et al, 1997) are validated questionnaires and useful in diagnosis and evaluation of treatment effectiveness (Lubeck et al, 2001; Sirinian et al, 2005).

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease criteria: Since IC/BPS is unknown etiology clinical symptom complex, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease criteria was created to rule in/out this diagnosis (Gillenwater and Wein, 1988; Nordling, 2004; Oberpenning et al, 2002) (Table 38–1).

To be diagnosed with interstitial cystitis, patients must have either |

Glomerulations on cystoscopic examination or a classic Hunner’s ulcer |

And either |

Pain associated with the bladder or urinary urgency |

An examination for glomerulations should be undertaken after distention of the bladder under anesthesia to 80–100 cm of water pressure for 1–2 minutes |

The bladder may be distended up to two times before evaluation. |

The glomerulations must |

Be diffuse—present in at least 3 quadrants of the bladder |

Be present at a rate of at least 10 glomerulations per quadrant |

Not be along the path of the cystoscope (to eliminate artifact from contact instrumentation) |

The presence of any one of the following criteria excludes the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis:

|

Tuberculosis of the bladder may cause true ulceration but is most apt to involve the region of the ureteral orifice that drains the tuberculous kidney. Vesical ulcers due to schistosomiasis cause symptoms similar to those of interstitial cystitis. The diagnosis is suggested if the patient lives in an area in which schistosomiasis is endemic. Nonspecific vesical infection seldom causes ulceration. Pus and bacteria are found in the urine. Antimicrobial treatment is effective.

Oral medication: Pentosan polysulfate provides protective coating in the bladder and suppose to reduce IC/BPS-related pain (Parsons and Mulholland, 1987). However, a randomized study has shown no significant benefit of the medicine over placebo (Nordling, 2004; Sairanen et al, 2005; Sant et al, 2003). Cyclosporine A has been shown to be more effective than pentosan polysulfate; however, its toxicity limits the usage (Sairanen et al, 2005). Anticholinergics are frequently used to control frequency and urgency. Amitriptyline has shown to improve IC/BPS symptoms including pain and frequency.

Instillation therapy: Hydrodistention under anesthesia can improve symptoms. Intravesical instillations of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), heparin, bacille Calmett-Guerrin (Mayer et al, 2005), and sodium hyaluronate (Riedl et al, 2008) are also used with some benefits (Chancellor and Yoshimura, 2004).

Other therapy: Other nonspecific medications, such as analgesics, anti-inflammatory agents, gabapentin, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors, can be used. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (Comiter, 2003) and biofeedback therapy may have some benefit for controlling the symptoms (Peters et al, 2007). Diet modification to avoid certain foods or drinks may have a role in the treatment (Chaiken et al, 1993).

Surgical therapy: Surgical therapy is rarely indicated. Even after cystectomy, some patients continue to experience pain (Baskin and Tanagho, 1992). For those who have small bladder capacity, augmentation procedure can be indicated. Recent trials of botulinum toxin A injection in the bladder wall have shown to improve symptoms and bladder capacity.

Most patients respond to one of the conservative measures mentioned previously. IC/BPS is a chronic condition and requires patient understanding and support.

Numerous objects have been found in the urethra and bladder of both men and women. Some of them find their way into the urethra in the course of inquisitive self-exploration (Cardozo, 1997; Mastromichalis et al, 2011). Other objects can migrate in the bladder through erosion. Commonly reported objects are intrauterine contraceptive devices (Bjornerem and Tollan, 1997; Chuang et al, 2010; Hick et al, 2004). Other foreign bodies placed during surgery include hernia repair mesh (Bjurlin and Berger, 2011), drain, vaginal sling material, and bone fragments after trauma (Stone et al, 1995).

The presence of a foreign body causes cystitis. Hematuria is not uncommon. Embarrassment may cause the victim to delay medical consultation. A plain x-ray of the bladder area discloses metal objects. Nonopaque objects sometimes become coated with calcium. Cystoscopy visualizes them all.

Cystoscopic or suprapubic removal of the foreign body is indicated. If not removed, the foreign body will lead to infection of the bladder. If the infecting organisms are urea splitting, the alkaline urine (which causes increased insolubility of calcium salts) contributes to rapid formation of stone on the foreign object.

So many mucous membranes are affected by allergens that the possibility of allergic manifestations involving the bladder must be considered. Hypersensitivity is occasionally suggested in cases of recurrent symptoms of acute “cystitis” in the absence of urinary infection or other demonstrable abnormality. During the attack, general erythema of the vesical mucosa may be seen and some edema of the ureteral orifices noted. Sometimes, lesions mimic malignancy (Salman et al, 2006; Thompson et al, 2005). Biopsy of the bladder wall reveals diffuse eosinophilic cell infiltrations (eosinophilic cystitis) (Popescu et al, 2009; Rubin and Pincus, 1974).

A careful history may reveal that these attacks follow the ingestion of a food not ordinarily eaten (eg, fresh lobster). Sensitivity to spermicidal creams is occasionally observed. If vesical allergy is suspected, it may be aborted by the subcutaneous injection of 0.5–1 mL of 1:1000 epinephrine. Control may also be afforded by the use of one of the antihistamines. Steroid therapy is effective for severe cases (Watanabe et al, 2009). Skin testing has shown positive in some cases.

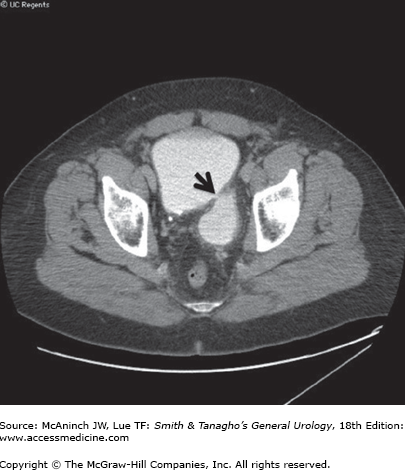

Most vesical diverticula are acquired and are secondary to either obstruction distal to the vesical neck or the upper motor neuron type of neurogenic bladder. Increased intravesical pressure causes vesical mucosa to insinuate itself between hypertrophied muscle bundles, so that a mucosal extravesical sac develops (Figure 38–4). Often this sac lies just superior to the ureter and causes vesicoureteral reflux. The diverticulum is devoid of muscle and therefore has no expulsive power; residual urine is the rule, and infection is perpetuated. If the diverticulum has a narrow opening that interferes with its emptying, transurethral resection of its neck will improve drainage. Carcinoma occasionally develops on its wall (Prakash et al, 2010). Micic (1983) discovered 13 diverticula harboring malignant tumors: nine transitional cell tumors, two squamous cell tumors, and two adenocarcinomas. Gerridzen and Futter (1982) saw 48 cases of vesical diverticula. Transitional cell tumors were found in five of these patients, but almost all the rest had abnormal histopathology: chronic inflammation and metaplasia. These authors stress the need for visualizing the interior of diverticula during endoscopy. Lack of wall thickness in diverticula makes potential early invasion of tumor and can results in poor prognosis (Yu et al, 1993). Diverticulectomy can be successfully performed laparoscopically (Khonsari et al, 2004; Kural et al, 2009; Macejko et al, 2008). Endoscopic management of bladder outlet obstruction must be performed, if a diverticulectomy is performed.

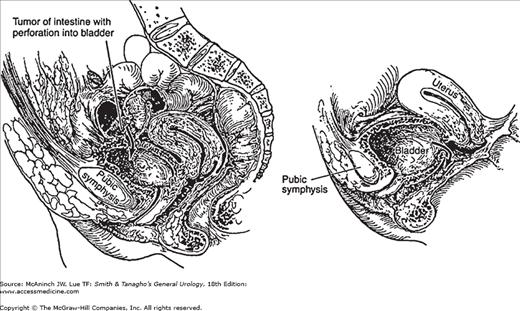

Vesical fistulas are common. The bladder may communicate with the skin, intestinal tract, or female reproductive organs (Figure 38–5). The primary disease is usually not urologic. The causes are as follows: (1) primary intestinal disease—diverticulitis, 50–60%; cancer of the colon, 20–25%; and Crohn’s disease, 10% (Badlani et al, 1980; Simoneaux and Patrick, 1997); (2) primary gynecologic disease—pressure necrosis during difficult labor; advanced cancer of the cervix (Chapple and Turner-Warwick, 2005; Gilmour et al, 1999); (3) treatment for gynecologic disease following hysterectomy, low cesarean section, or radiotherapy for tumor (Ayhan et al, 1995); and (4) trauma. Ablative therapy of prostate cancer such as, cryosurgery or high intensity focused ultrasound therapy, is a frequent cause of rectourethral fistula, but development of rectovesical fistula is rare.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree