Introduction

Colonic diverticula are false diverticula—that is, pockets composed of mucosa and submucosa that have herniated through weaknesses in the colon wall at the points where intramural vasa recta penetrate the inner circular muscle of the bowel ( Fig. 48-1, A and B ). The generally accepted pathophysiology of diverticulitis centers on a diverticular microperforation causing a bacterial infection. A possible alternative mechanism suggesting that diverticulitis may be a primary inflammatory process has been proposed. When the inflammation resolves uneventfully, the diverticulitis is described as uncomplicated. In contrast, patients who experience clinical sequelae as a result of diverticulitis are described as having complicated diverticulitis ( Box 48-1 ). The presence of a phlegmon or simple extraluminal gas demonstrated on cross-sectional imaging is not considered complicated disease. This chapter will focus on specific aspects of sigmoid diverticulitis, including presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and clinical management.

Free perforation

Abscess

Sepsis

Intestinal obstruction

Ureteral obstruction

Colon stricture

Fistula

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Presentation

The severity of presentation of diverticulitis ranges from mild to life threatening, depending on the extent and duration of inflammation and peritoneal contamination. Patients with sigmoid diverticulitis typically describe worsening left lower quadrant abdominal pain. According to the lay of the sigmoid loop, some patients may experience right-sided or suprapubic pain, and nonspecific symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation, fever, or diarrhea may be present. Dysuria may be reported in cases in which the inflamed colon abuts the bladder, and small bowel obstruction may occur when a loop of small bowel is kinked by an inflammatory attachment to the colon. Patients with fistulizing disease may describe pneumaturia, fecaluria, abnormal vaginal discharge, or a draining skin sinus.

Physical examination typically reveals a febrile patient distressed by pain with tenderness in the lower abdomen. Signs of localized peritoneal inflammation, such as rebound tenderness and guarding, often can be elicited. A phlegmon may be appreciated upon palpation. Psoas or obturator signs also may be present because of the inflammatory process. Patients with severe diverticulitis can be hemodynamically unstable with signs of diffuse peritonitis, whereas at the other end of the spectrum, patients with recurrent episodes may recognize an attack early and present when signs are still minimal.

Diagnostic Evaluation

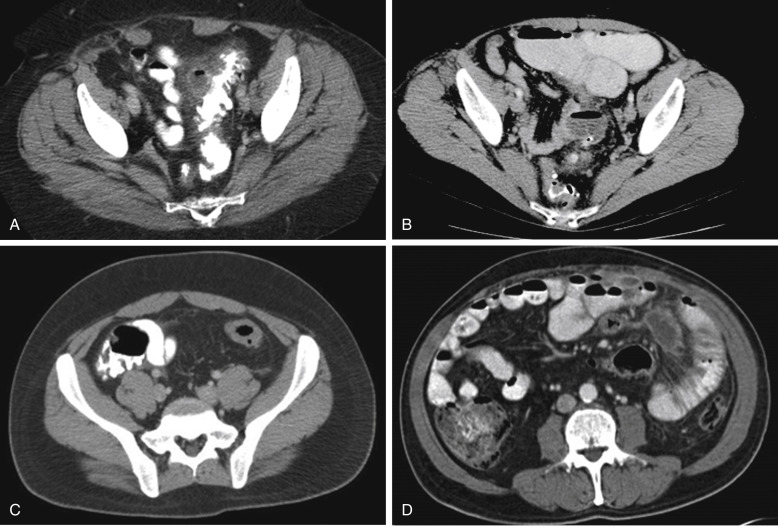

Although the constellation of left lower quadrant tenderness, fever, and leukocytosis is suggestive of sigmoid diverticulitis (especially in patients with recurrent diverticulitis whose diagnosis has been previously confirmed), other possible diagnoses should be considered ( Box 48-2 ). Urinalysis and plain abdominal radiographs are helpful in excluding urinary tract infection, kidney stones, and bowel obstruction. Because of the superiority of cross-sectional imaging compared with other types of evaluation, a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the most appropriate initial imaging in patients with suspected diverticulitis. Multislice CT imaging with intravenous and intraluminal contrast material has excellent sensitivity and specificity that is reported to be as high as 98% and 99%, respectively. CT findings consistent with diverticulitis may include colon wall thickening, mesenteric fat stranding, phlegmon, extraluminal gas, abscess, stricture, and fistula ( Fig. 48-2, A-D ). Patients who have early or mild diverticulitis and immunocompromised patients whose ability to mount an appropriate inflammatory response is limited may not demonstrate these typical inflammatory changes. A major benefit of CT imaging is its ability to diagnose other disease processes that may mimic the presentation of diverticulitis. An additional unique benefit provided by CT scanning is the ability to grade the severity of diverticulitis, which has been shown to correlate with risk of failure of nonoperative management, recurrence of infection, persistence of symptoms, and the long-term development of strictures and fistulas.

Colon cancer

Appendicitis

Irritable bowel syndrome

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ischemic colitis

Bowel obstruction

Gynecologic disease

Urologic disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree