Functional constipation

Diagnostic criteriaa must include two or more of the following in a child with a developmental age of at least 4 years with insufficient criteria for diagnosis of IBS:

Two or fewer defecations in the toilet per week

At least one episode of fecal incontinence per week

History of retentive posturing or excessive volitional stool retention

History of painful or hard bowel movements

Presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum

History of large diameter stools which may obstruct the toilet

Functional nonretentive fecal incontinence

Diagnostic criteriab must include all of the following in a child with a developmental age at least 4 years:

Defecation into places inappropriate to the social context at least once per month

No evidence of an inflammatory, anatomic, metabolic, or neoplastic process that explains the subject’s symptoms

No evidence of fecal retention

Using a single clinical feature, such as low bowel frequency, to define constipation can be misleading. It has been shown that around 0.4–20 % of otherwise healthy children have at least one feature of Rome III criteria [5, 6]. Furthermore, bowel frequency is known to be variable in different regions of the world possibly depending on diet, genetics, and environmental factors [5, 7]. Therefore, it is imperative that the clinician’s perspective is more flexible and he or she understands the changes in bowel frequency in the context of local and patient variables.

Several studies have assessed the diagnostic capability of Rome III criteria to identify functional constipation in children. A school-based study including 10–16-year-olds showed Rome III criteria are more inclusive in diagnosing constipation [8]. Another study based on outpatients referred to a tertiary care hospital noted that 87 % of children had constipation according to Rome III criteria, whereas only 43 % children were classified as having defecation disorders using Rome II criteria [9]. Although both these studies indicate the superiority of Rome III criteria in the diagnostic process, the required duration of 2 months appears to be a little too long and may result in delayed treatment, especially in older children.

Magnitude of the Problem

Constipation is a global health problem. Studies from Europe showed a prevalence range from 0.7 to 17.6 % among children [9–14]. In the USA, 10 % of 5–8-years-olds are having constipation [6].

Two studies from Brazil pointed out alarmingly higher rates of over 20 % occurrence of constipation in a 1–10-year-old population [14, 15]. More disturbing data are emerging from Asia. The prevalence of constipation in Taiwan was 32.2 % in children in elementary schools and in Hong Kong 12–28 %, indicating constipation is becoming a bigger problem in newly developing economies from Asia [16–18]. Similarly, developing nations in Asia like Sri Lanka also show 15 % of their school children are suffering from chronic constipation [19]. These data underscore the magnitude of the disease burden and are shifting its epicenter of prevalence from the West to the East. The differences in prevalence need to be interpreted with some caution as the wider variations seen may partly be due to differences in definitions used, differences in age groups included, and heterogeneity of survey methods.

Risk Factors

Table 21.2 shows the known and identified risk factors for chronic constipation in children. In contrast to adult studies which show constipation to be more prevalent among females, several epidemiological studies among children have failed to identify gender as a risk factor to develop constipation [13, 20, 21]. However, one study from Sri Lanka has shown that the prevalence is significantly higher among boys and children living in low socioeconomic status [19].

Table 21.2

Risk factors for chronic constipation

Category | Risk factor |

|---|---|

Patient related | Male sex |

Poor sleep | |

Obesity | |

Dietary | Low fiber |

Consumption of junk food | |

Not having regular meals with parents | |

Cow’s milk protein allergy | |

Psychological | Home-related stresses |

School-related stresses | |

Adverse life event including abuse | |

Subjected to bullying | |

Anxiety | |

Depression | |

Autistic spectrum disorders | |

Social | Living in war-affected areas |

Living in urban areas | |

Lower social class | |

Hostile and aggressive family environment |

Psychological stress is another risk factor that predisposes children to develop constipation. Children living in homes and studying in schools which create stress are more prone to develop chronic constipation [22]. In addition, disrupted societies by civil unrest are also an important predisposing factor [23]. A study from Hong Kong has shown that children not having regular meals with their parents and deprivation of sleep as independent risk factors to develop severe constipation [17]. Moreover, low consumption of fiber [11, 17, 18], cow milk protein (CMP) hypersensitivity [21, 24], and consumption of fast foods too often [17] are associated with constipation . Lastly, obesity has also been identified as an independent risk factor [25, 26]. In a recent study, our group also noted that children who faced adverse life events such as physical, emotional, and sexual abuse have higher predilection to develop constipation. These events also predispose them to develop more somatic symptoms and lead to a poor quality of life [27].

Quality of Life

Children with constipation have poor health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) scores in all domains, namely social, school, physical, and emotional functioning. The scores they obtained are even lower than children suffering from organic diseases such as gastroesophageal reflux and inflammatory bowel disease [28]. Children with slow transit constipation also have been shown to have poor HRQoL [29]. A school-based study from Sri Lanka also confirms these findings and showed that constipation-associated fecal incontinence (FI) further reduces HRQoL [30].

Extraintestinal Symptoms and Psychological Problems

Children with constipation suffer from an array of somatic symptoms. In one of the studies, we found that children with constipation had a multitude of somatic symptoms and high somatization scores [30]. Constipation is also associated with a number of behavioral abnormalities such as autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and anxiety [31–33]. Abnormal personality traits were also noted in children suffering from constipation [34]. In addition, children with autistic spectrum disorders are known to have very early onset disease [32].

Health-Care Burden

Constipation is a leading cause for medical consultation in children. Documented medical visits for constipation were higher than most other gastrointestinal diseases in children under 5 years [35]. The incidence of medical presentation for children with constipation is substantially higher than other chronic episodic conditions such as asthma (seven times) and migraine headaches (three times) [36]. The mean outpatient costs and mean annual number of emergency room visits are higher in children with constipation compared to controls [36]. Furthermore, employed parents with a child with constipation have a higher number of working day losses than controls. More importantly, children with constipation are noted to have higher number of days of school absenteeism [37]. In addition, children with constipation show poor quality of school work [30, 38]. Implications of these findings on education of children are much larger than expected. Poor education invariably leads to poor earning capacity and ignorance as an adult. Therefore, they become an added burden to society at large.

Pathophysiology

Understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic constipation in infants and children is a considerable challenge and remains in its early stages. However, available studies on physiology of the colon and rectum and studies on animal models have shed some light upon the subject.

Infants and Young Children

Stool withholding plays a major role in the development of constipation in infancy and early childhood. Passing a hard stool leading to pain, strict early toilet training, stubbornness, and concentration on other activities which are more exciting than going to the toilet are possible factors for stool withholding. When the urge to pass stools comes, the withholding child tightens gluteal muscles and stands on tip toe. During this process, the rectum dilates, fecal matter is accommodated, and desire to pass stools disappears. A large mass of feces is formed in the rectum during this process leading to a cascade of physiological changes described below.

Children and Adolescents

Several studies have shown that children with constipation have defective intraluminal transport involving different segments of the colon such as proximal delay, hind gut delay, and rectosigmoid hold up [39–41]. Furthermore, it has been shown that children with chronic constipation have significantly delayed total colonic transit times of over 100 h [42]. Although slow transit constipation in adults is almost exclusively found in females [43], in children and adolescents , prevalence is more or less equal among the sexes [44].

Colonic manometry has shown several abnormalities in constipation. They include reduced frequency of high-amplitude propagative contractions and disordered patterning of spatiotemporal colonic propagative responses [45]. Like slow transit constipation, all these factors may contribute to poor propulsion of fecal masses along the colonic lumen generating symptoms of constipation.

Rectal sensitivity to oncoming fecal matter and dilatation is a crucial point in normal rectal function. There is a subset of children with constipation who demonstrate poor rectal sensation [46]. Furthermore, several studies in children have shown increased rectal compliance [47, 48] and a megarectum [49]. These factors are closely interrelated and lead to attenuation of rectal sensation and lack of desire to evacuate, leading to low bowel frequency.

In addition, contraction, rather than relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles with increasing rectal pressure (dyssynergic defecation), also prevents evacuation of stools. The balloon expulsion test has been used to measure rectal motor dysfunction in children with an array of other combined measurements. Chitkara et al. demonstrated that 31 % of children with functional constipation and 53 % of children with functional fecal retention (using Rome II criteria) had an abnormal balloon expulsion test, and 40 % had high resting anal pressure [50].

In addition to these local factors, dysfunction of the brain–gut axis also contributes to the development and propagation of symptoms. Stress-induced abnormalities in the colonic motor activity may further aggravate the motor and sensory abnormalities and worsen stool retention. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have described a multitude of abnormalities in adults with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGD) including constipation as possible mechanisms for this phenomenon [51].

Final Pathway for Both Age Groups

Pathophysiological mechanisms described for both age groups finally lead to retention of stools in the rectum and colon. Since colonic and rectal mucosa are designed to absorb water, stool becomes dry and hard. Molecular abnormalities in the rectal mucosa of children with constipation, such as abnormalities in non-calcium-mediated chloride channels, lead to abnormally low chloride secretion that may further contribute to the development of hard stools [52]. The mechanical dilatation of the rectum inhibits motor function of the proximal and distal hemi-colon through reflex mechanisms [53, 54].

In addition, animal models have shown that accumulation of feces elongates the colon. This in turn leads to the release of nitric oxide by activating mechano-sensory and myenteric descending neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Nitric oxide inhibits action potential firing in other myenteric sensory neurons driving peristaltic nerve circuits, inhibiting colonic contractile activity (occult reflex), thereby seriously hampering evacuation [55, 56]. It has been shown that children with increased rectal wall compliance have prolonged colonic transit time which further strengthens the possibility of occult reflex [47]. Interactions of these inextricably linked mechanisms in a complex manner, rather than in isolation, lead to generation and propagation of symptoms in children with constipation.

Clinical Features

Infants and Young Children

The most common reason for constipation in infants and toddlers is an acquired behavior component after experiencing painful bowel movements [57]. When the desire to pass a stool occurs, they tend to cry and withhold stools by tightening their gluteal muscles and pelvic floor. This is evident in infants as they tighten the legs and in young children as they stand on tip toe and tighten their muscles till the desire for passing a stool goes off. These children also have low stool frequency, passing large-diameter, rock-hard, and sometimes bloody stools infrequently and occasional leaking of semisolid to liquid stools into underwear. In addition, poor appetite and abdominal distension are also notable features.

Older Children and Adolescents

This group tends to present with classic symptoms of constipation. The presenting complaint very often is reduced stool frequency. The other features include passing hard stools, pain while passing stools, frequent episodes of FI , and infrequent passage of a large-diameter stool which may obstruct the toilet. Some older children also show withholding postures although these are not seen as commonly as in younger children. Abdominal bloating is another important feature in children and seen especially in adolescents [58]. Abdominal pain, anorexia, and behavioral abnormalities are also important features in this age group.

Clinical Evaluation of Children with Defecation Disorders

Clinical evaluation is the most important tool in diagnosing defecation disorders in children and adolescents . It includes a thorough history, tenacious physical examination, and careful interpretation of findings in a logical manner. This process helps to actively identify functional defecation disorders, exclude possible organic diseases that can mimic functional defecation disorders, and recognize complications.

Clinical History

Although the presenting features are obvious in the majority, clinical features may be subtle in some children. Therefore, a high degree of suspicion is essential during history taking. Onset and duration of symptoms need to be clarified first. Very early-onset disease in infancy suggests the possibility of organic diseases such as Hirschsprung disease, anorectal malformations, and metabolic diseases. Details of bowel habits are the cornerstone in diagnosing constipation (Box 21.1). Use of validated stool scales for infants [59] (Amsterdam stool scale) and children (modified Bristol stool scale) [60] helps to obtain more accurate description of stools. Apart from that, it is also important to question on other gastrointestinal symptoms. Abdominal pain is noted in 10–70 % of children with constipation. Poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal bloating are other important features that need to be inquired into during history taking. Children with chronic constipation also tend to suffer from a myriad of somatic symptoms and identifying these features would help in clinical management [19]. Urinary symptoms and incontinence are also seen in some children [61–64] and refractory vulvovaginitis is a known feature, especially in prepubertal girls [65] .

Box 21.1 Bowel Habit Questions for Defecation Disorders

Stool frequency

Consistency

Nature of the stools

Incontinence

Withholding behavior

Pain during defecation

Blood in stools

Past medical history, specially concentrating on drugs that may cause constipation, is also an important part in the evaluation. Surgical issues such as corrected anorectal malformations and Hirschsprung disease are well known to present with constipation [66, 67]. Dietary history particularly concentrating on fiber content is an integral part as underconsumption of fiber may lead to constipation [17, 18]. Introduction of cow’s milk to the infant’s diet is a risk factor to develop constipation among them [68, 69]. Psychological abnormalities also need to be looked into as some children develop personality problems, anxiety, and depression with constipation [22, 70]. Finally, details of social and family history should not be overlooked. Constipation is notably prevalent in children from the lower socioeconomic strata, living in disrupted deprived areas and urban areas [19, 23]. In addition, adverse life events such as physical, sexual, and emotional maltreatment should also need to be evaluated carefully in children with constipation as these factors are known to predispose children to develop constipation [27]. Some children with constipation also have first-degree relatives with similar problems [11, 19] .

Physical Examination

The physical examination should start with assessment of growth. Growth faltering and short stature are features of organic causes (endocrine, metabolic, etc.) for constipation. On the other hand, obesity is also a known predisposing factor for defecation disorders such as constipation and FI [26]. Dysmorphic features are present in children with syndromes who are having constipation [71]. All children with defecation disorders need a good developmental assessment. Those with long-term neurological dysfunctions such as cerebral palsy tend to have both constipation and FI. Furthermore, this would also help to identify children with autistic spectrum disorders who have a tendency to develop constipation [31] .

Abdominal examination may reveal the presence of abdominal distension and past surgical scars of abdominal surgery. Palpable fecal masses in the lower abdomen indicate fecal loading and is a feature present in about 50 % of children with constipation [72]. However, gaseous distension is more in favor of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (“IBS-C”) .

Perianal examination may reveal abnormal position of anus [73]. Smear of feces and perianal excoriation of skin indicates FI . Fissures and tags can also be noted in children with chronic constipation who pass hard stools or may indicate sexual abuse. Patulous anus is associated with lower motor neuronal damage which can be associated with FI. Digital examination of the rectum is an essential part in evaluating children with defecation disorders . During the process one should assess resting tone, the squeeze pressure of the sphincter complex, nature of fecal loading, size of the fecal mass, and the size of the rectum.

Neurological examination should concentrate specially on features of spina bifida, motor and sensory deficits in the lower limbs, and perianal sensory testing. One should look for perianal sensory loss and absence of anal wink .

Investigations

Constipation is a clinical diagnosis. Using currently accepted clinical criteria, the majority of the children who present to a medical facility can be diagnosed and managed successfully. Specialized investigations are therefore only needed when the diagnosis is uncertain, or when they do not respond to standard management strategies. Investigations are also warranted in children who are suspected to have organic reasons for defecation disorders during history taking and physical examination.

Radiological Tests

Colonic transit time is usually assessed by using radiological methods. It generally gives an idea of propulsive function of the colon and helps to identify segments with abnormal motility. It is usually measured using radiopaque markers or scintigraphic methods. In marker studies, the markers are ingested as a meal or swallowed as a capsule, and abdominal X-rays are obtained to count the number of markers in different segments of the colon. In scintigraphy, the patient is given a meal containing radioisotope, and multiple images are taken using a gamma camera to assess the radioisotope count in each region. Several studies have shown abnormalities in total and segmental transit times in children with functional constipation using radiopaque markers [39, 40]. A Dutch study noted children with functional constipation having colonic transit time over 62 h. This cutoff value has a sensitivity of 52 % and specificity of 91 % [42]. Colonic transit time also has an inverse relationship with the number of defecations per week [39]. Using colonic scintigraphy, Sutcliffe et al. found delay in transit in patients with constipation [41].

Ultrasonography has also been used to assess the degree of fecal retention in the rectum. Using a transabdominal approach, several studies have measured the rectal diameter to determine fecal loading in the rectum using different methods and have shown that children with chronic constipation do have a larger rectal diameter compared to controls. Bijos et al. using recto–pelvic ratio (dividing the transverse diameter of the rectal ampulla by the transverse diameter of the pelvis) illustrated that in children with functional constipation, the mean recto–pelvic ratio was 0.22 ± 0.05 compared to healthy controls 0.15 ± 0.04 [74]. Another study measured the impression of the rectum behind the urinary bladder seen as a crescent. The median rectal crescent in children with constipation was 3.4 cm (range 2.10–7.0; interquartile range (IQR) 1.0) as compared with 2.4 cm (range 1.3–4.2; IQR 0.72) in healthy controls [75]. Klijn et al. also found a significant difference in mean rectal diameter between the constipated group (4.9 cm) and the control group (2.1 cm). The cutoff value was 3.3 cm, where > 3.3 cm indicated constipation [76]. The results are promising, and wider availability and noninvasive nature of the test make it an ideal investigation. However, methods need to be standardized, and more studies are needed before recommending routine use of ultrasonography in assessing children with constipation.

Furthermore, using endosonography techniques, Keshtgar et al. have shown that children with chronic constipation have a thickened external anal sphincter complex. However, they were unable to demonstrate a significant relationship between thickened anal sphincter, anorectal manometry, and amplitude of sphincter contractions [77]. The clinical utility value of this finding is yet to be determined.

Plain abdominal X-ray is used to demonstrate fecal loading in the colon and rectum. Several scoring systems are used to assess the degree of impaction. However, sensitivity and specificity of these tests are variable and also the inter- and intra-observer reliability are poor [78]. Therefore, it is difficult to recommend the use of plain X-ray films of the abdomen as an investigation.

The other radiological investigations such as defecography and contrast enemas have no place in clinical evaluation of children with constipation. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spinal cord is an important investigation in children with refractory defecation disorders as some children have been shown to have significant abnormalities such as spina bifida occulta and terminal filum lipoma. Importantly, gluteal cleft deviation was found in three of four patients with these abnormalities [79, 80].

Physiological Tests

Anorectal manometry combined with balloon expulsion test is an important investigation to understand the function of the anorectal unit and pelvic floor muscles. It provides information about anal sphincter function, mechanisms of continence and defecation, rectal sensation, rectal compliance, and anorectal reflexes [81]. A number of studies have demonstrated several abnormalities of anorectal function in children with constipation. They include increased rectal sensory threshold, reduced rectal contractility, high resting anal pressure, and failure of relaxation of the external anal sphincter with rising rectal pressure [46–49]. Furthermore, a subset of children was found to have an abnormal balloon expulsion test [50]. Feinberg and coworkers have shown that there is a correlation between the number of FI episodes and the volume of first urge, and high volume required to elicit rectoanal inhibitory reflex. They also found a significant correlation between the presence of withholding behavior and the maximum volume tolerated [82].

Colonic manometry allows the measurement of pressure/force from multiple regions within the colon in real time [83] and helps to discriminate between normal colonic physiology and colonic myopathies and neuropathies. A number of colonic motor patterns have been identified, such as antegrade high-amplitude propagating contractions, low-amplitude propagating sequences, non-propagating contractions, and retrograde propagating pressure waves [84]. In contrast to conventional manometry which used a limited number of sensors, arrival of high-resolution manometry allows researchers and clinicians to study three-dimensional pressure plots to study gastrointestinal pathophysiology more closely. An elegant study using this technique has clearly shown children with slow transit constipation having definitive abnormal motor patterns (post-bisacodyl-induced high-amplitude propagatory contractions) which can serve to diagnose colonic neuropathy [85].

Other Investigations

Association between CMP allergy and constipation is still a debatable subject. Two research reports from Italy (from a center of excellence studying allergies) have found association between constipation and CMP sensitivity [68, 69]. A more recent study from Irastorza and colleagues found 51 % patients with constipation responding to a CMP elimination diet, but no significant differences were noted between the group of responders and nonresponders regarding atopic/allergic history and laboratory results [86]. Therefore, testing for CMP allergy is not recommended. Importance of hypothyroidism as an etiological factor for constipation in children is overstated. Bennett and Heuckeroth studied 56 children with hypothyroidism and noted that only one child had constipation as the presenting complaint [87]. As for other serological tests (such as screening for celiac disease and looking for hypercalcemia), these are also not recommended in all constipated children; however, in a child with symptoms not responding to laxative therapy, it might be useful to look for celiac disease.

Management

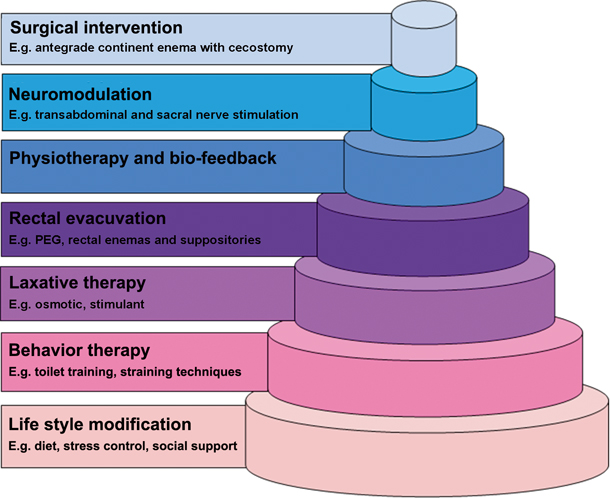

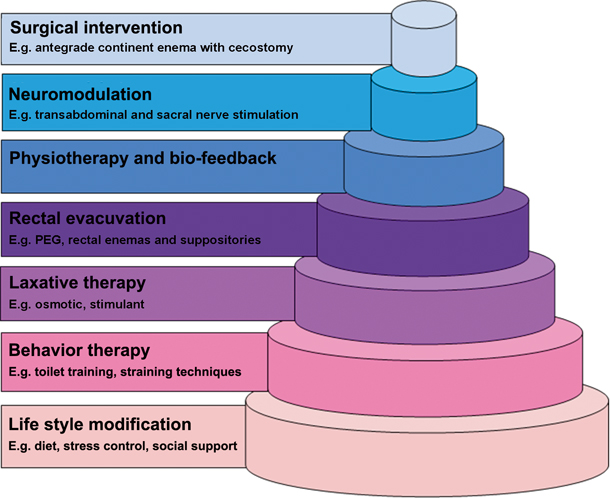

Effective management of constipation requires a multifaceted approach. A stepwise management protocol is shown in Fig. 21.1. The main steps include lifestyle modification, toilet training, use of laxatives and enemas, biofeedback therapy, nerve stimulation, and surgical interventions. However, it is important to realize that the data in the pediatric literature to support evidence-based use of treatment strategies are limited, especially regarding old laxatives such as lactulose and bisacodyl. Therefore, the management mostly depends on individual experiences and limited number of trials of new drugs.

Fig. 21.1

Stepwise management of constipation

Lifestyle Modifications

Constipation is known to be associated with psychological stress related to home, school, and society [22, 23]. These factors need to be addressed during the consultation. Children with psychological stress need to be identified and coping mechanisms need to be taught as part of the day-to-day lifestyle. Home- and school-related punishment is another factor that is known to predispose children to develop constipation which can easily be avoided [27].

Although widely believed, a high-fiber diet does not relieve constipation. Several trials including different types of fibers failed to show any clinically meaningful therapeutic benefit in children [88–90]. Two systematic reviews also illustrate limited clinical value of fiber in the management [91, 92]. In addition, increasing dietary fiber intake with extensive behavioral interventions does not reduce the requirement of laxatives [93]. Similarly, increase in the consumption of water has also shown not to increase stool frequency or soften stools [94].

Toilet Training and Behavioral Therapy

Stool withholding plays a crucial role in developing constipation in young children. Aiming to prevent this phenomenon, children with constipation need to relearn to properly pass stools in the toilet.

As the first step, negative attitude regarding stools needs to be eliminated. This facilitates and prepares the child mentally to pass stools in the toilet or potty. Child is encouraged to use the toilet regularly usually after each meal as the gastrocolic reflex facilitates generation of high-amplitude propagatory contractions which help to evacuate stools. The proper seating method (upright posture) to bring the anorectum to the correct angle to facilitate the passage of stools also needs to be taught. Proper positioning of legs and relaxing them with the pelvic floor and anal sphincters also can be learned. Once the child masters these techniques, it is necessary to teach him/her proper straining methods to facilitate the passage of stools. This process needs to be a regular practice and could be encouraged with a reward system. [95]. A Cochrane review has shown positive evidence indicating that adding behavioral therapy to conventional laxatives has benefits in treating children with constipation [96]. It is obvious that behavioral therapy alone cannot cure constipation. However, given the importance of the part played by stool-withholding behavior in childhood constipation (especially in infants and younger children), toilet training and behavioral modifications are inseparable parts in day-to-day clinical management.

Fecal Disimpaction from Rectum

It has been shown that 40–100 % of children with constipation have a large rock-hard fecal mass in the rectum [97]. After evacuation of the fecal mass children are more likely to respond to maintenance therapy [98]. Several studies have proved that oral administration of polyethylene glycol (PEG) is both successful and cost-effective in the majority of children with fecal impaction [99–101]. Therefore, oral route is recommended as the initial step in rectal evacuation.

Rectal enemas or suppositories are recommended for children who do not respond to oral drugs. A study by Bekkali et al. failed to show a significant difference between PEG and rectal enemas on evacuation of rectum loaded with feces [101]. However, it is imperative to realize the invasive nature of rectal therapy specially when the child has pain, discomfort, and may suffer from morbid fear of manipulations around the perianal region by medical professionals. In a minority of cases, even sedation is recommended before rectal administration especially when the child is not cooperative. Rectal medications that can be used are phosphate, docusate sodium, mineral oil enemas, and bisacodyl suppositories.

Maintenance Treatment

Once disimpaction is achieved, it is imperative that the clinician should concentrate on maintenance therapy. This facilitates passage of stools and prevents re-impaction. Table 21.3 shows the details of the drugs that are currently used in the management of childhood constipation.

Table 21.3

Dosages of most frequently used oral and rectal laxatives

Drug class | Drug | Dosages |

|---|---|---|

Osmotic laxatives | Lactulose | 1–2 g/kg, once or twice/day |

PEG 3350 PEG 4000 | Maintenance: 0.2–0.8 g/kg/day Fecal disimpaction: 1–1.5 g/kg/day(with a maximum of 6 consecutive days) | |

Milk of magnesia (magnesium hydroxide) | 2–5 years: 0.4–1.2 g/day, once or divided 6–11 years: 1.2–2.4 g/day, once or divided 12–18 years: 2.4–4.8 g/day, once or divided | |

Fecal softeners | Mineral oil < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|