Cow’s milk allergy

Antonio Nieto MD, PhD

Angel Mazón MD

Introduction

Allergy to cow’s milk (CM) proteins appears mainly in infants and persists for several months or years, or may even be lifelong. Allergic reactions to CM are frequent (1-2% of infants)1,2,3,4. Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) constitutes a challenge for paediatricians, who must be aware of the condition, and know how to initiate diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Adverse reactions to foods

The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology divides adverse reactions to foods into toxic and nontoxic. If an immunological mechanism is involved they are denominated allergic: the classic allergic reactions are termed IgE mediated (7.1), and the classic intolerance to CM proteins is now termed non-IgE-mediated allergy (7.2). The nontoxic reactions, which are not mediated by an immunological mechanism, are now termed intolerance.

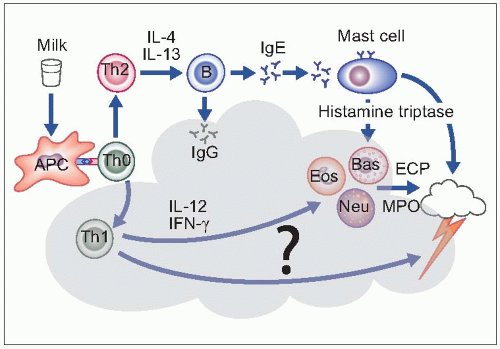

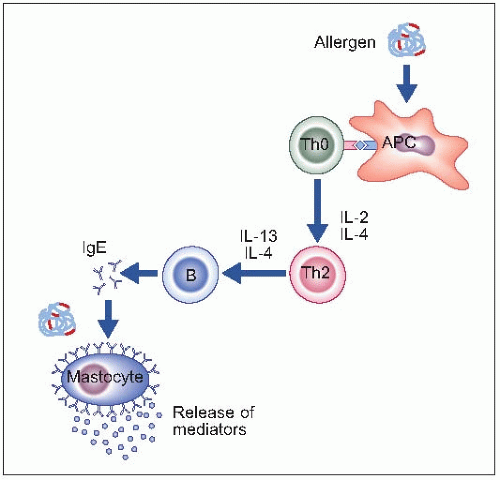

7.1 A protein which acts as an allergen is captured by an antigen-presenting cell (APC). This interacts with a nonprimed Th0 lymphocyte, which under certain conditions, such as presence of interleukin-2 and IL-4, derives into a Th2 type lymphocyte. This interacts with a B-lymphocyte that, under the influence of IL-4 and IL-13, synthesizes specific IgE against the allergen. The IgE binds to the high affinity IgE receptors on the surface of cells, such as mastocytes. Upon a subsequent contact of the allergen, this binds to two molecules of IgE, and this interaction drives the immediate release of mediators (histamine, tryptase, leukotrienes). The mediators cause the different symptoms of allergic reactions, depending on the target organ. |

Proteins are the agents that cause allergic reactions. The basic units of proteins are amino acids. The molecular weight of amino acids ranges from 89 to 204 Da. The primary structure of proteins is a chain of amino acids bound to each other through their acid (-COOH) and amino (-NH2) terminals. The amino acids can occur in short chains of 6-9 amino acids (called peptides) or long chains of hundreds of amino acids. It is important to notice the molecular weight to estimate the number of amino acids that can be found in a peptide or a protein.

There are several casein proteins, whose molecular weight is around 21 kD, and which comprise around 200 amino acids. Although the absolute amount of whey proteins is lower, the number of different proteins is greater as are their molecular weights (Table 7.1). A patient can be sensitized to only one or more than one protein.

The human breast does not synthesize β-lactoglobulin. Thus, any content in human milk comes from the dietary intake. A regular infant formula contains about 300 mg of β-lactoglobulin per 100 ml. Human milk contains around 0.42 µg%. A few drops of formula contain as much lactoglobulin as 100 litres of human milk. These few drops contain as much lactoglobulin as the amount present in human milk that a lactating mother gives in 3 or more months. No wonder that a child who is sensitized to CM but has no symptoms while being breast-fed develops overt severe symptoms the first time that he is given a bottle of formula.

Clinical picture

Group A comprises signs and symptoms associated with a demonstrated IgE sensitization to foods. These symptoms disappear when the offending food is withdrawn, and reappear when the patient is challenged with it. The classical symptoms appear immediately after ingestion or contact with the allergen. They can show as urticaria-angioedema involving skin and mucosa; digestive symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pains or cramps, and diarrhoea, or respiratory symptoms including wheezing, difficult breathing, and rhinoconjunctivitis. The most severe disorder is anaphylaxis.

Table 7.1 Cow’s milk proteins | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Group B includes patients who often have a sensitization to foods. Some patients have an IgE sensitization, and respond to avoiding/challenging with the food in the same way that group A does. Nevertheless, other patients who are also sensitized have no clinical response to diet, and the course remains irrespective of diet. The group B includes mainly atopic dermatitis. In cases of a complete or partial response to avoiding and challenging, it is usually not immediate, but takes several hours or even days to be evident. Pathogenic mechanisms not mediated by IgE may be involved. Some infants with CMA have isolated haematochezia and are otherwise healthy. Eosinophilic infiltration of one or several portions of the digestive tract can appear in children with CMA: it is diagnosed by the eosinophilic count in biopsy samples. Depending on the affected portion it causes dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, gastro-oesophageal reflux, abdominal pain or cramps, diarrhoea of variable severity, occult or overt blood in stools.

Group C includes diseases in which no IgE mechanism is identified. They have a good clinical response to the

elimination of the offending food. The most frequent disorder in group C is what was formerly called intolerance to CM proteins. When diarrhoea is present, malabsorption can appear and lead to failure to thrive or to specific nutritional deficits.

elimination of the offending food. The most frequent disorder in group C is what was formerly called intolerance to CM proteins. When diarrhoea is present, malabsorption can appear and lead to failure to thrive or to specific nutritional deficits.

Diagnostic approach

When first facing a child with a clinical picture suspicious of CMA, the initial approach is based on a good clinical history (Table 7.2). The three first issues may orientate the physician towards a higher or lower probability of allergy, but their usefulness is very limited. The two last issues are much more informative about the suspect mechanism of reaction.

It is important to try to identify if the patient has an IgE or non-IgE reaction. The allergologic tests try to identify if there is specific IgE against CM proteins5. This is accomplished with the use of skin prick tests, and the quantification of specific IgE in serum. Both tests have a good specificity but a more modest sensitivity (Table 7.3). As some patients have discordant responses in the tests, performing both gives the best yield, but even so some patients will be misclassified as non-IgE responders. The positivity of any of the tests proves that there is a sensitization to CM; the relationship of sensitization with clinical symptoms must be clarified through the interpretation of the clinical history or performing challenge tests. Sensitization to other allergens must be assessed: it is not surprising to find out that the patient is sensitized to other allergens, especially hen’s eggs.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of food allergy is the double-blind placebo-controlled challenge test. This is often required for investigational studies, but in the routine clinical practice an open challenge is acceptable (Table 7.4). The protocol must be adapted to every child, taking into account the clinical history, previous reactions, and results of tests (Table 7.5). More caution must be taken for those with positive IgE tests, while those with negative tests usually tolerate greater amounts, and the protocol can be performed more rapidly. Several days must elapse until a negative response can be ascertained. The test is easily interpreted as positive when immediately evident typical reactions appear, and easily interpreted as negative when there is a long follow-up time without symptoms. However, between these extremes are found a range of responses that are difficult to interpret. Thus, repeated challenges are sometimes needed until a clear interpretation can be reached. The positive response to the challenge test permits a diagnosis of allergy, but it cannot identify which mechanism is involved. The allergologic evaluation is complete when IgE tests and the challenge are performed (7.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree