Constipation, Disorders of Defecation, and Anal Pain

R. John Nicholls

Ian Lindsey

I hav finally kum to the konklusion, that a good reliable sett ov bowels iz wurth more tu a man, than enny quantity of brains.

—HENRY WHEELER SHAW (JOSH BILLINGS): His Sayings

A man should always endeavor to keep his bowels lax; they may even approach a diarrheal state. For this is a leading rule in hygiene, as long as the bowels are constipated or when they act with difficulty, serious disease ensues.

—SCHULCHAN ARUCH: Code of Jewish Law

▶ CONSTIPATION AND DISORDERS OF DEFECATION

Introduction

Patients who present with constipation may have a mechanical reason for it or the condition may be functional. In the latter case, the defect may be due to a slow transit issue or to difficulty in evacuation of the rectum. Frequently, both factors are present in the same individual. Constipation is a common reason for patients to visit their physician; the causes are myriad (Table 20-1).

Delayed transit can be present in bowel of normal caliber or with gross dilatation. In the latter circumstance, this is in the form of an aganglionic or idiopathic megabowel (usually chronic), or it may be acute as in pseudoobstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome—see later).255 Normal caliber constipation occurs in patients who consume insufficient dietary fiber. The condition may also be caused by other factors, such as age, institutionalization, immobility, drugs, metabolic disorders (hypothyroidism, hypercalcemia), depression, and neurologic disease.

Evacuation difficulty or obstructed defecation can be broken down into mechanical (anatomical) and functional (pathophysiologic) causes, although overlap is common, and occasionally multiple factors are involved. In the past 10 years, there has been a move away from surgery for those with functional constipation due to delayed transit, with a greater number of patients receiving behavioral treatments such as biofeedback and neuromodulation.

Epidemiology

In the United States alone, the cost of over-the-counter laxatives for 1991 was in excess of $400 million. Today, the outpatient medical care of American women who suffer with constipation is twice as costly as for those who do not.56 The prevalence in the general community of the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and so-called functional constipation has been reported to be between 20% and 30% in each case.146 Sandler and colleagues investigated the association between self-reported constipation and several demographic and dietary variables in 15,014 men and women 12 to 74 years of age who were examined between 1971 and 1975 at the time of the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.294 Overall, 12.8% reported constipation, but this correlated poorly with stool frequency. Nine percent of those with daily stools and 30.6% of those with four to six stools per week noted that they were “constipated.” Constipation was more common in blacks (17%), in women (18%), in individuals older than 60 years of age (23%), and in those who were inactive, had low income, or of the lower socioeconomic class. Constipated individuals reported lower consumption of cheese, dry beans and peas, milk,

meat and poultry, beverages (sweetened, carbonated, and non-carbonated), and fruits and vegetables. They reported higher consumption of coffee or tea. They consumed fewer total calories even after controlling for body mass and for exercise.

meat and poultry, beverages (sweetened, carbonated, and non-carbonated), and fruits and vegetables. They reported higher consumption of coffee or tea. They consumed fewer total calories even after controlling for body mass and for exercise.

TABLE 20-1 Nonmechanical Causes of Constipation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Classification

Constipation may be mechanical or nonmechanical. The former can be caused by any obstructing lesion outside the bowel wall, within the wall, or inside the lumen. These conditions are dealt with in specific chapters on carcinoma, diverticular disease, volvulus, and other mechanical causes of obstruction. Painful anal disease may also result in constipation through the reluctance of the patient to defecate. This ultimately can lead to fecal impaction.

Nonmechanical causes of constipation are shown in Table 20-1. They include conditions that result in reduced intestinal transit. The causes of the various forms other than aganglionosis are unknown, but delayed transit appears to be divisible into involvement of the entire intestine (including gastric function) and involvement confined to the large bowel—so-called colonic inertia.279 This distinction is usually established by isotope scintigraphy, a study that can measure gastric emptying as well as orocecal and colonic transit. Patients with reduced transit are divided into those with a normal caliber colon and those with a dilated colon or rectum or both (megabowel).

Obstructed defecation is a common cause of constipation. The etiology may be mechanical, such as from rectal carcinoma or stricture, or it may be functional. Functional, obstructed defecation may be caused by failure of the pelvic floor adequately to relax as in anismus. This may include the condition of the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, or it may be due to laxity of the pelvic floor and be associated with perineal descent and/or rectocele.369 The diagnosis may be based on the Rome III criteria,199 and its severity can be assessed by the Cleveland Clinic Constipation Score.1 Another scoring system, the KESS score was devised to distinguish constipation from normal patients and to discriminate between those with slow-transit constipation (STC), obstructed defecation, or both.171 In a study of 71 individuals with constipation and 20 asymptomatic controls, this scoring system is closely correlated with the Cleveland Clinic score (r = 0.9) and achieved a clear separation from patients with STC and defecation, although it was not able to distinguish those with a combined disorder. The common causes of nonmechanical constipation are shown in Table 20-1.

Pathophysiology

In constipation, there is a degree of colonic sensorimotor dysfunction. The colon demonstrates myoelectric activity, which can result in phasic and tonic contractile activity. In many cases, there is a reduction in the rate of colonic transit. Scintigraphy has shown that the motility disorder is more extensive in some patients who demonstrate delayed gastric emptying and delayed orocecal transit. This is referred to as whole gut dysmotility.22,279 Degeneration and fibrosis of the intestinal muscle is seen in familial visceral myopathies. These involve genetic and mitochondrial abnormalities, which result in reduction in intestinal motility.2 The genetic abnormality may be highly specific in, for example, alpha-actin deficiency.176

Motility

The physiology of colorectal sensorimotor activity is dealt with in Chapters 2 and 7. Research in intestinal physiology, however, is difficult and may explain why little is understood despite many attempts to record motility and measure sensation. One of the main reasons is that motor patterns such as the migrating motor complex or colonic mass action occur at a frequency over time base longer than the convenient recording of intraluminal pressure. It is very difficult to obtain recordings over many hours. Yet only by doing so is it possible to study the changes in intestinal motility with time.

The basic motility activities of the colon are a slow net distal propulsion, extensive kneading, and exposure of its contents to the mucosal surface.295 Material in the bowel is moved along a pressure gradient, with the rate and volume related to the pressure differential, the diameter of the tube, and the viscosity of the contents.188 It may take only 1 or 2 hours for a meal to traverse the small intestine, but it may frequently take up to 30 hours to pass through the colon. The length and diameter of the colon tend to favor prolonged contact between the contents and the absorptive mucosa; this increases the amount of water removed and, as a consequence, may yield hard stools.193 Additionally, widening of the rectosigmoid can produce a capacious distal reservoir; hence, a larger fecal mass is required to stimulate elimination.193

The pathophysiology of constipation is still poorly understood. It is characterized by reduced colonic motility, dysfunctional rectal emptying, and rectal hyposensitivity.298 The first of these may coexist with a panintestinal motility disorder evidenced by delayed gastric emptying and retarded orocecal transit time.279 Neural connections of the rectum include pathways to the dorsal ganglia of the spinal cord, ascending spinothalamocortical tracts and projections to the insular and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. Rectal neural function may also be influenced by psychological factors.353 Additionally, impaired rectal sensation is frequently found in patients with idiopathic constipation.12

At the time of publication of the previous edition of this book, the normal range of colorectal motor activity and its

variations in disease had yet to be clearly defined,188 but there was evidence that chronic constipation might be associated with either increased or decreased colonic motility.164 Colonic motility relies upon there being normal smooth muscle and a competent enteric nervous system modulated by the intact autonomic parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves. Smooth muscle cells are formed into a syncytium with interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), which together result in a rhythmic myogenic activity. Peristalsis is the synchronized contraction of colorectal smooth muscle, which, when the muscle fibers shorten, results in propulsion. Research into colonic motility has mostly involved pressure recordings from multichannel catheters introduced at colonoscopy or via a nasogastric tube. The former requires bowel preparation that may affect the activity.38

variations in disease had yet to be clearly defined,188 but there was evidence that chronic constipation might be associated with either increased or decreased colonic motility.164 Colonic motility relies upon there being normal smooth muscle and a competent enteric nervous system modulated by the intact autonomic parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves. Smooth muscle cells are formed into a syncytium with interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), which together result in a rhythmic myogenic activity. Peristalsis is the synchronized contraction of colorectal smooth muscle, which, when the muscle fibers shorten, results in propulsion. Research into colonic motility has mostly involved pressure recordings from multichannel catheters introduced at colonoscopy or via a nasogastric tube. The former requires bowel preparation that may affect the activity.38

Three forms of colonic motility patterns have been identified. They are as follows:

Nonpropagating. These are random waves of a frequency of 2 to 4 per minute. They comprise the majority of the activity and are suppressed at night.

Propagating sequences. These may be of high amplitude. They may be antegrade or retrograde. In the normal colon, the former outweigh the latter by about 3/1. These also are suppressed at night.

Colorectal motor complexes. These are periodic contractions in the sigmoid and rectum of unknown function. They are more prevalent at night and have an amplitude of 80 to 90 mm Hg, occurring every 3 to 30 minutes.38

Defecation

Defecation begins with involuntary filling of the rectum through caudally passing migratory contractions from the proximal colon. This leads to rectal sensory awareness through the sampling reflex, which in turn promotes urgency.236 As the rectum continues to fill, the urgency increases and rectal contraction with relaxation of the internal sphincter follows. Inhibition of pelvic floor tone then occurs, and the pelvic floor descends with simultaneous contraction of the longitudinal muscle of the anal canal.38,295

If a voluntary effort is required to defecate, intra-abdominal pressure is increased by closure of the glottis and by contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor (resisting the forward movement of stool and closing the lumen distally). The diaphragm descends, and the voluntary muscles of the abdominal wall are contracted, creating a closed system.372 Relaxation of the pelvic muscles produces descent of the pelvic floor and straightening of the previously angulated rectum. Closure of the anal canal by the sphincters allows an increase of pressure within the rectum so that subsequent sphincteric inhibition results in expulsion of stool. When paradoxical contraction of the voluntary sphincter muscle occurs during attempts at evacuation, it is termed “obstructed defecation” or “anismus” (see later). The point at which complete inhibition of the external sphincter occurs can be demonstrated experimentally with an intrarectal balloon. When the volume reaches 150 to 200 mL of air, the intrarectal pressure achieves 45 to 55 mm Hg. At the end of defecation, when straining is discontinued, the pelvic floor rises to its normal position and again obliterates the lumen. A rebound contraction of the anal sphincter occurs; this has been termed the closing reflex.262

Berman and colleagues subdivided patients with disorders of defecation into three categories: those with motility (i.e., transit) problems, those with mural difficulties (e.g., internal procidentia), and those with musculoskeletal problems (e.g., obstructed defecation).29 Kuijpers applied the colorectal laboratory in the diagnosis of 74 patients with so-called functional constipation.186 Outlet obstruction was noted in approximately three-fourths, with abnormal transit times identified in two-thirds. These results imply that only after evacuation studies have been proved to be normal should the physician embark on transit studies. Karasick and Ehrlich also suggested based on their studies that constipation is often a disorder of defecation rather than an impairment of colonic motility.159 However, Roe and colleagues believed that the most useful investigations were transit studies and defecography.288 Grotz and coworkers performed a study to identify differences in rectal wall contractility between healthy volunteers and those with chronic severe constipation.111 In response to feeding of a cholinergic agonist and a smooth muscle relaxant, rectal wall contractility was decreased in constipated patients. The authors concluded that these findings suggested the presence of an abnormality of rectal muscular wall contractility in constipated patients.111 To identify the optimal regimen for the management of intractable constipation, Wexner and Dailey offered an algorithmic approach.366

Etiology

The classification of constipation in Table 20-1 shows that many factors can be responsible. Essentially, they all influence bowel function either by slowing intestinal transit or by inhibiting rectal evacuation.

In a useful review of the subject, Müller-Lissner and colleagues considered many issues that have been invoked as causes of constipation, some of which have been substantiated by evidence and some not.244 The colon has three functions: absorption of water; the harboring of bacteria, which split fiber into absorbable nutrients; and the retention and expulsion of the residue when convenient to the individual. Among misconceptions that have been disproved, there is no evidence for the retention of stool in the large bowel causing “autointoxication” as propounded by Arbuthnot Lane in the early 20th century. Also, there is no evidence for a lengthened, nondilated colon, a so-called dolichocolon, as a cause for the condition.228,324

Dietary Fiber and Water Intake

Fiber binds water, but when split by bacteria, it no longer does so. No difference has been found in dietary fiber intake in constipated compared with nonconstipated individuals. In a study of various fiber preparations, an inverse relationship between fecal bulk and water holding has been identified, suggesting that dietary fiber does not have its effect on stool weight by increasing water retention in the intestine.319 In another study, 9 constipated women were compared with 9 nonconstipated women in the third semester of pregnancy. There was no difference in the ingestion of fiber in the two groups. In a further 40 constipated women in the third trimester, dietary fiber manipulation had no effect on bowel function.6 Müller-Lissner and colleagues concluded that a poor fiber diet should not be assumed to be the cause of constipation, but it may contribute to the issue.244 Some are helped and others are made worse by fiber. The available data do not indicate that bowel frequency can be manipulated to a clinically useful degree by the ingestion of liquids. There is no evidence that constipation can be treated by increasing liquid intake unless the patient is dehydrated.

Immobility

During sleep, colonic motility is almost absent. There is no difference between constipated and nonconstipated individuals at

these times.21 There is, however, evidence that physical activity is associated with a higher stool frequency,39 so an association can be quite marked in runners.329

these times.21 There is, however, evidence that physical activity is associated with a higher stool frequency,39 so an association can be quite marked in runners.329

In a survey of 201 elderly patients, the overall incidence of constipation was no different from that of younger patients, but within the groups, any association appeared to be related to immobility and to depression.69 Bedbound elderly patients are more likely to have constipation than those who are able to walk with help and even more so than do patients who walk several hundred meters per day.168

Constipation is often due to fecal loading in the rectum. Impaction is commonly seen in institutions where immobility and constipating drugs are both factors delaying transit and evacuation. Exercise improves bowel function in normal sedentary men and women,33 but not in patients who are already severely constipated.231 There is evidence from institutional studies that exercise, adequate hydration, and fiber intake can reduce the need for laxatives.158

Drugs

Drugs that cause constipation include opiates, anticholinergics, antidepressants, iron, bismuth, antiparkinsonians, aluminum-containing antacids, antihypertensives (diuretics, ganglion blockers, calcium channel blockers), and anticonvulsants. Drug-induced constipation is very common (see Chapter 4). The bowel symptoms and even the radiologic findings of colonic dilatation may completely resolve after the medication responsible has been discontinued.46

Laxatives

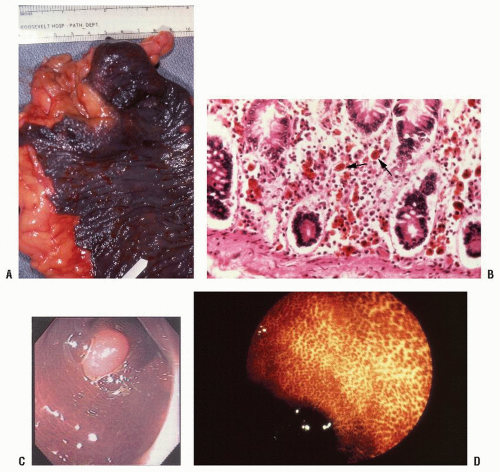

There is a large literature on whether laxatives can affect the structure and function of the intestine. Stimulant laxatives have been thought to cause damage to the myenteric nerves or smooth muscle causing impaired motility.77 Certainly, they can result in melanosis coli if used over time. This condition, first recognized by Cruveilhier in 1830, is caused by the deposition of pigment due to staining by anthraquinones of cell debris from colocytes ingested by macrophages in the submucosa (Figure 20-1).92 The condition is of no clinical significance and disappears within weeks to months of stopping the laxative. The effect of purgation on the enteric nerves and smooth muscle of constipated individuals was reported by Smith.310 He opined that any changes seen might have been due to the primary condition itself, rather than to secondary damage by the laxatives. Furthermore, ultrastructural changes seen in patients on long-term laxatives may also occur in amyloid, diabetic autonomic neuropathy, and inflammatory bowel disease.284 Other studies have demonstrated reduced numbers of Cajal cells and enteric neurons in patients with severe colonic inertia.122,364 These changes may be due to the disease and not to any laxative medication. When patients taking anthraquinones were compared with a control group of constipated patients not taking laxatives, there was no evidence in favor of laxatives causing any damage.283 Thus, the evidence that laxatives can cause intestinal nerve and smooth muscle damage per se is poor.

LÉON JEAN BAPTISTE CRUVEILHIER (1791-1874)

|

Cruveilhier was the son of a military surgeon who had planned to enter the priesthood, but he was denied this course by his father who wanted him to become his successor. He attended the University at Limoges and in 1810 moved to Paris to study medicine under Guillaume Dupuytren, a friend of his father. Dupuytren made him his protégé and aroused his interest in pathology. Cruveilhier received his doctorate in medicine in 1816 with a dissertation on a new classification of organs according to their pathologic changes. Stung by failure to secure an appointment as surgeon in Limoges, he returned to Paris and, supported by Dupuytren, was appointed professor agrégé of surgery at the Faculty of Medicine of Montpellier. In 1825, he accepted the position of professor of descriptive anatomy in Paris and the following year was named Médecin des Hôpitaux. In 1836, he was elected to the Académie de Médecine and became president in 1839. In 1836, he was offered the first chair of pathologic anatomy, which had been established with funds from his teacher, Dupuytren. He remained in this position for more than 30 years. The vast material from the deadhouse of the Salpêtriàre, the establishment of the Musée Dupuytren, and the lectureship in morbid anatomy provided the impetus for his prolific writings. His best known work was Anatomie pathologique du corps humain in which he reports the first pathologic account of disseminated sclerosis. Cruveilhier devoted himself to his enormous practice, following the rules of a very strict ethic that he condensed in his Des devoirs et de la moralité du médecin (1837). He died on his country estate in Sussac near Limoges at the age of 83. (With appreciation to Faisal Aziz, MD.)

Laxatives can cause electrolyte disturbances when taken in high doses. In a special article, Müller-Lissner discusses whether or not the cathartic colon exists.243 In a series of 200 patients with diarrhea, the incidence of laxative abuse was 3.5%.43 Review of the literature demonstrated 70 publications, including 240 patients in whom diarrhea was caused by sub rosa laxative administration. Of these, 95% were female; the laxative in question was phenolphthalein, and the metabolic disturbance was hypokalemia.192

Metabolic and Endocrine

Sex Hormones

In children, constipation is more common in boys than in girls, but after the age of 14, females vastly exceed males with this problem.269 There is evidence that bowel function may be related to the menstrual cycle, but no difference in colonic transit was found during the follicular and luteal phases (48 and 51 hours).130,150 There is, however, evidence that transit time is increased in pregnancy.359 In another study, 26 female patients with severe constipation were compared with 23 age-matched, normal healthy women.151 There were significant differences during the follicular phase in progesterone, hydroxyprogesterone, cortisol, and testosterone levels. Parenthetically, ultrasound studies have failed to demonstrate any abnormality in the female genital organs in constipated patients.156

Other Hormones

Gastrointestinal hormones have been studied in patients with constipation.350 Twelve individuals with severe constipation were compared with 12 healthy normal women after taking a radioisotope-labeled meal. Circulating gastrointestinal hormones were measured over the following 180 postprandial minutes. Levels of somatostatin were increased in the constipated patients, but there was no correlation with upper gastrointestinal transit rates. Pancreatic glucagon and entero-glucagon levels were lower, but there were no significant differences in insulin, gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP 1), cholecystokinin (CCK), gastrin, pancreatic polypeptide (PP), motilin, neurotensin, and peptide tyrosine-tyrosine (PYY).

Abnormal levels of thyroid hormones have been regarded as causes of constipation or diarrhea, but in a prospective study, there was a low prevalence of hypothyroidism in female patients with constipation.11 The authors recommended testing for thyroid function if there were other features of thyroid underactivity.

Other

Hypercalcemia, hypokalemia, and porphyria can all be associated with constipation. In the case of hypokalemia, this may be the result of excessive intestinal losses by purgatives (see Laxatives).

Psychological

It is accepted that constipation may be associated with psychological abnormalities, particularly depression. In a study of 25 consecutive patient referrals who harbored severe constipation, 10 with normal transit had higher psychological distress than the 15 with increased transit. When compared with 25 normal controls, the authors concluded that different therapeutic approaches may be required based on behavioral and psychological assessment.358 In a subsequent study of 38 patients with severe idiopathic constipation, the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) score was higher in 15 patients with normal transit compared with 23 in whom it was prolonged.357 In addition, those with depression may develop constipation as a consequence of antidepressant drug treatment.

Neurologic Disease

Neurologic disease at almost any level of the nervous system can cause constipation. These include multiple sclerosis and diabetes mellitus, both leading to autonomic neuropathy.101 The mechanisms of action are complex and not well understood. Autonomic dysfunction may reduce motor intestinal function and diminish the defecation reflex activity through impairment of anorectal sensation.272 Intracranial diseases such as cerebrovascular accident, tumor, and Parkinson’s disease can all be associated with problems of bowel elimination. Other contributing neurologic conditions include lesions of the spinal cord, cauda equina injury, meningomyelocele, spina bifida, and tertiary syphilis.

Smooth Muscle Dysmotility

Connective tissue disorders that may be associated with constipation include systemic lupus, dermatomyositis, and scleroderma.55,213,292,302,315 In fact, most patients with scleroderma have intestinal involvement.370 This leads to dysmotility, owing to the involvement of the smooth muscle. Muscular dystrophy and amyloid may cause a secondary incompetence of the intestinal muscle.

Assessment and Investigation

The most common causes of constipation encountered in practice include constipation-predominant IBS, drugs, depression, and inadequate consumption of fiber and liquid. Once a mechanical cause has been excluded, the likely reasons for constipation in patients with a normal colonic caliber include STC or an evacuation disorder.

Clinical Assessment

The words “constipation” or “diarrhea” when used by the patient may not truly be referring to bowel frequency and may therefore be misinterpreted by the physician. There are three elements that the clinician should take into account: frequency of defecation (expressed as the number of bowel actions per 24 hours or per week), the consistency of the stool, and the presence of urgency. The term constipation may be used by the patient when there is any difficulty with evacuation.

Some patients feel constipated because they have an unproductive urge to defecate or feelings of incomplete evacuation that prompt them to return to the bathroom and to continue further attempts at evacuation by straining at stool. The need for accurate symptom assessment requires the clinician to obtain details of straining, urgency, and incomplete evacuation, taking stool consistency into account.

Urgency is usually not applicable to constipation, but if present, it should be recorded as the number of minutes the patient requires in order to get to the bathroom when the desire to defecate comes on.

Patients with an evacuation disorder of the type seen in the solitary ulcer syndrome may make numerous fruitless visits to the bathroom where they may remain, stay straining for many minutes up to hours. Ten or more visits to the bathroom in a 24-hour period are not uncommon in this group of patients, and the time spent there may often be more than 30 minutes. In such cases, it is helpful to compute the total time per 24 hours spent in the bathroom. In exceptional cases, this may amount to several hours.

It is important to document the presence of abdominal symptoms such as pain, discomfort, and distension. The general well-being of the patient as judged by appetite, weight, and energy levels should also be assessed. A family and drug history should be obtained and a dietary assessment made. Any history of prior surgery, neurologic disease, and mental illness should be noted.

The examination should include a neurologic assessment. Any distension of the abdomen or mass suggesting a mechanical cause or fecal impaction should be noted. The anorectal examination should record the state of the rectum, whether capacious, empty, or full of feces. With a fecal impaction, the anal sphincter may be patulous. In Hirschsprung’s disease and anismus, the sphincter may feel hypertonic. In patients with neurologic disease, including spinal cord injury, the sphincter is usually quite lax.

Investigations

Colorectal examination by means of colonoscopy or imaging is necessary in patients with symptoms suggestive of a mechanical cause or those with a family history of large bowel cancer. In individuals who do not need such investigation, it is reasonable to treat the patient in general terms before carrying out any further studies.

Most patients with constipation can be managed in a primary care setting with attention to likely causative factors and with simple targeted interventions. Withdrawal of medication, adjustment of diet, and other lifestyle changes such as exercise should be attempted, unless it is clear that these measures are unlikely to be successful. Thus, a patient with a long history of evacuation difficulties and who has tried laxatives without improvement is likely to require further investigation. This includes tests to estimate intestinal transit and to determine whether there is an evacuation disorder.

Specialist referral should be considered, but it is uncommonly undertaken given the vast number of patients attending primary care who harbor a constipation problem.

Colonic Function

Plain Abdominal X-ray and Barium Enema

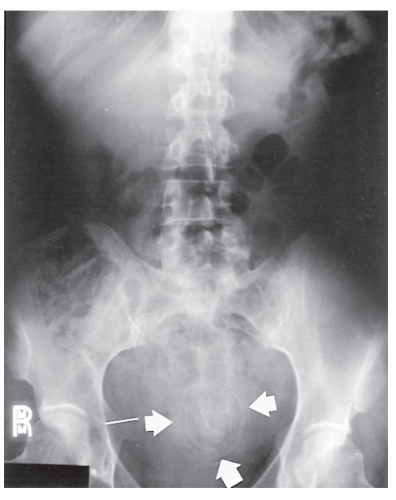

Occasionally, a plain abdominal x-ray will show fecal loading of the large bowel (Figure 20-2), but this investigation is generally of limited value in the investigation of constipation. It may have some usefulness in determining whether the bowel is distended or not. In the past, a barium enema (Figure 20-3) would have been requested, but this investigation is performed less, often owing to the availability of computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

If the colon or rectum is dilated, then aganglionic bowel disease, idiopathic megabowel (megacolon), or pseudoobstruction should be considered. The distinction between them is obvious and will be described later.

Intestinal Transit

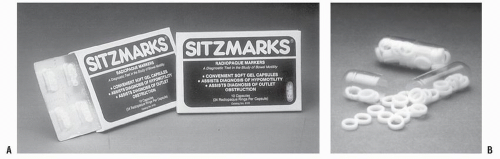

Marker Studies. In clinical practice, transit is measured by following the intraluminal passage of a radiopaque or radioactive marker detected by conventional radiology and scintigraphy, respectively. Essentially, this will be normal or may be delayed, such as in STC.68 The use of radiopaque markers was initially described by Hinton.131 In this evaluation, 20 to 50 radiopaque gelatin capsules are given on day 0 and day 5. Delayed transit is inferred if more than 20% of the markers are still present at 5 days (Figure 20-4). Alternatively, capsules of different shape may be given on days 0,1, and 2, followed by an abdominal x-ray on day 5.233 It can be argued that this allows an assessment of transit through different segments of the colon (Figure 20-5), although regional

retardation of transit within the large bowel is not accepted by all workers in the field. The investigation will be positive in about one-half of the patients with STC.175 Radiopaque markers are inexpensive, easy to use, and are widely available.322 In the United States, the commercially produced rings, Sitzmarks, are generally employed for this purpose (Figure 20-6).

retardation of transit within the large bowel is not accepted by all workers in the field. The investigation will be positive in about one-half of the patients with STC.175 Radiopaque markers are inexpensive, easy to use, and are widely available.322 In the United States, the commercially produced rings, Sitzmarks, are generally employed for this purpose (Figure 20-6).

FIGURE 20-2. Fecal impaction. A large, laminated pelvic calcification (arrows) is indicative of a retained, massive fecaloma. |

FIGURE 20-4. Plain abdominal radiograph showing radiopaque markers primarily in the sigmoid colon, a distribution consistent with hindgut inertia. |

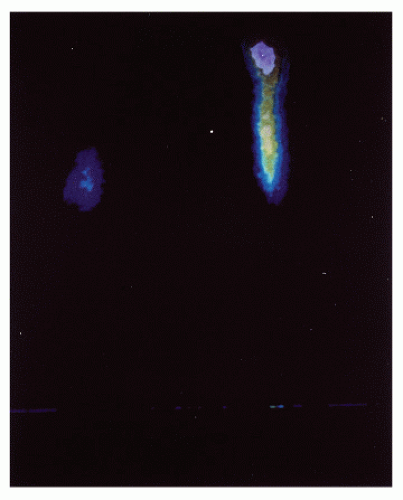

The second method of assessing transit is scintigraphy. Krevsky and colleagues gave oral111In bound to diethylene-triaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) followed by a gamma scan at 72 and 96 hours and scanned the abdomen at intervals after ingestion.183 Others have used111In mixed with charcoal in a methyl acrylate capsule, which is then broken down in the gut to release the radionuclide in the terminal ileum and cecum.42,45,227 There is some variation in the technique, but all protocols share common aspects. Any constipating medications should be stopped 48 hours prior to undertaking the study. The patient should have fasted from the previous day. A standard meal with contained carbohydrate, fat, and protein commensurate with the normal relative contents of these foodstuffs is then ingested. This contains a radionuclide label of111In of 99Tc in solid and liquid phase. Imaging is started immediately by gamma scanner recording to estimate gastric emptying. This is continued for 6 hours and thereafter at 24, 48, and 72 hours.37,222,301 The transit time is determined by the location of the center of the mass of radioactivity at the selected interval from ingestion (Figure 20-7).68 This technique allows measurement of gastric emptying, orocecal transit, and colonic transit.

Colonic Manometry

Colonic manometry is another technique that has been used to estimate transit and has been advocated by some workers.20,277 It involves the siting of open-tipped or balloon probes into the intestine via the anus or nasal orifice. This is often difficult to accomplish. Recording must be

maintained for many hours to give a meaningful picture of the motility of the intestine. There is much published in the literature, but owing to the methodologic difficulty and the individual variation of intestinal behavior, there is little standardization of the method. At the present time, manometry is more a research tool than a method of clinical investigation.

maintained for many hours to give a meaningful picture of the motility of the intestine. There is much published in the literature, but owing to the methodologic difficulty and the individual variation of intestinal behavior, there is little standardization of the method. At the present time, manometry is more a research tool than a method of clinical investigation.

Rectal Evacuation

Many patients with STC will have evidence of impaired rectal evacuation. Thus, patients who have transit studies should also have investigations to determine whether there is impairment of evacuation. These include manometry, balloon expulsion, defecography, and magnetic imaging of the pelvic floor.369 Measurement of perineal descent using the perineometer formed the subject of much research 30 years ago but has never become part of clinical practice.125,145

Anal Manometry

Anal manometry has a limited role in the investigation of obstructed defecation (see Chapter 7). Patients who have a lax pelvic floor may have reduced resting tone and impaired voluntary contraction, but such findings are not useful in management. In those with anismus, resting anal pressure may be increased. Attempts at defecation may be associated with paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle, although the validity of this effect has been questioned. Ambulant manometry is technically difficult and is confined to research.

Balloon Expulsion

In this investigation, the patient lies in the left lateral position.16,270 A catheter with an inflatable balloon is introduced into the rectum, and 50 mL of liquid (originally barium suspension) are injected into the balloon. The patient is then asked to evacuate. Failure to accomplish this is an indication of obstructed defecation.

Defecography

Defecography was originally developed by Kerremans in 1952167 and subsequently modified by Mahieu in 1984.209,210 The procedure can demonstrate a rectocele, enterocele, rectal intussusception, and anismus.119,120 The investigation is generally well tolerated, inexpensive, and widely available in Europe, including the United Kingdom, but availability in the United States has been somewhat more problematic. The reasons for difficulty in obtaining this study in the United States apparently have more to do with lack of motivation on the part of some radiologists and possible financial reimbursement issues, rather than the availability of equipment and that of patient compliance. Its disadvantages include exposure to radiation and the inconsistent relationship between anatomical abnormality and functional disturbance as indicated by symptoms. Some patients experience embarrassment, but this issue should be avoidable through proper draping.

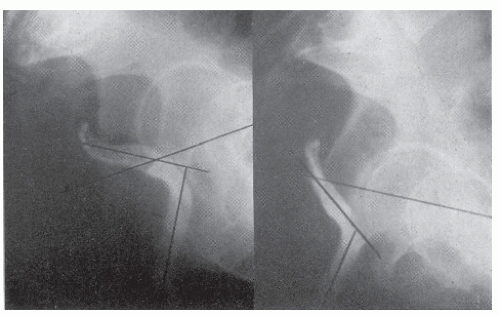

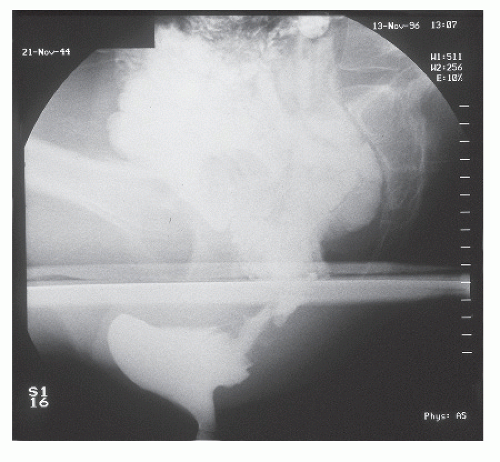

Approximately 120 mL of barium paste is introduced into the rectum, with the patient in the left lateral position. The patient then sits upright on a radiolucent commode (see Figure 7-13) after having taken 100 mL of barium sulfate suspension by mouth to opacify the small intestine (Figure 20-8). The examination includes imaging in three phases: at rest, during maximum voluntary contraction (squeeze), and expulsion (Figure 20-9). In the last of these, the patient makes three attempts at evacuation lasting 30 seconds to assess the ability of emptying. Digital fluoroscopy is used to minimize the radiation dosage.

In normal defecography, the anorectal angle is approximately 90 degrees, and the pelvic floor lies above the level of the ischial tuberosities. During squeeze, the pelvic floor rises, and the impression of the puborectalis muscle can be seen to be indenting the anorectal junction posteriorly. When the patient evacuates, the pelvic floor descends, and the anorectal angle opens to a wide angle. Barium is then expelled (Figure 20-10). This normally is complete in about 30 seconds (see also Figure 7-14).83

The radiologic signs must be interpreted with caution in light of the patient’s symptoms. Abnormalities such as

rectocele and rectal folds may be observed in nearly one-half of normal individuals.304 Rectocele is a common incidental finding and is often associated with signs of anismus, intussusception, and enterocele (see Chapter 21). A significant rectocele is defined based on its size and the degree of barium retention (trapping).118

rectocele and rectal folds may be observed in nearly one-half of normal individuals.304 Rectocele is a common incidental finding and is often associated with signs of anismus, intussusception, and enterocele (see Chapter 21). A significant rectocele is defined based on its size and the degree of barium retention (trapping).118

FIGURE 20-8. Defecography in a patient with difficulty in evacuation. Large rectocele and enterocele shown in the pouch of Douglas after administration of oral contrast. |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI began to be used for the assessment of the pelvic floor in the 1990s.31,124 It has the advantage of not involving ionizing radiation, but it is expensive and not generally available. To date, it has been used more as a research than as a clinical tool.

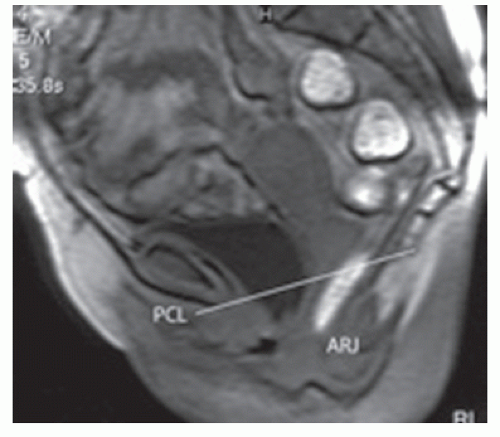

Closed or open MR machines are employed.31,291 No bowel preparation is necessary, and no vaginal or bladder contrast is required. The rectum is filled with a contrast resembling the consistency of soft feces for dynamic MRI defecography. Axial T2 images are followed by coronal and sagittal views at rest and during attempts at defecation. Views of the sequence from rest to straining back to rest are also obtained (Figure 20-11).

In a normal patient, the bladder neck and cervix lie above a line drawn from the inferior point of the pubic symphysis to the sacrococcygeal joint. During defecation, these structures move posteriorly and inferiorly but still remain above the line. The anal canal opens, and the impression of the pu-borectalis muscle is lost as the anorectal angle widens from its normal right angle to more than 120 degrees.

Clinical Forms

Normal Caliber Constipation

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Definition. IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) in which abdominal pain or discomfort is associated with defecation or a change in bowel habit and often with features of disordered defecation. There are no abnormal physical or radiologic signs, and there is no abnormal histopathology. The condition is identified by the presence of certain symptoms defined by the Rome III criteria (see later).199

Epidemiology. IBS, also known as functional bowel disease, mucous colitis, or spastic colon, is very common with an estimated prevalence in the general population worldwide of 10% to 20% and with a female predominance. The frequency of constipation varies according to how it is determined,

whether from the patient herself, by application of Rome criteria, or by the Bristol scale for intestinal transit. In a study in which these approaches were compared, approximately 8% had constipation by each definition, but only 2% were constipated by all three.254 This may lead to confusion of definitions.199

whether from the patient herself, by application of Rome criteria, or by the Bristol scale for intestinal transit. In a study in which these approaches were compared, approximately 8% had constipation by each definition, but only 2% were constipated by all three.254 This may lead to confusion of definitions.199

FIGURE 20-11. MRI showing a thick-section sagittal view during straining and with the bladder base and anorectal junction (ARJ) well below the pubococcygeal (PC) line. |

Diagnosis. IBS is diagnosed using the Rome criteria. There have been three meetings of experts that have been reported: Rome I,340 Rome II,341,342 and Rome III.199 The last two modifications divided patients into those with diarrhea-predominant and constipation-predominant IBS. Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days per month in the last 3 months should be part of the symptomatology.199 Pain has to be present, and this should be related to bowel function. Included also should be altered stool frequency, with straining another feature. The Rome II and III criteria have attempted to classify functional bowel disorders according to symptoms without investigation, but this approach is not very practical.373 Supportive symptoms that are not part of the diagnostic criteria include abnormal stool frequency (less than or equal to three bowel movements per week or more than three bowel movements per day), abnormal stool form (lumpy/hard stool or loose/watery stool), defecation straining, urgency or a feeling of incomplete bowel movement, passing mucus, and bloating.

For a diagnosis of IBD according to the Rome III criteria, two or more of the following should be present:

Straining during at least 25% of defecation

Lumpy or hard stools in at least 25% of defecations

Sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25% of defecations

Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for at least 25% of defecations

Manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25% of defecations (e.g., digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor)

Fewer than three defecations per week

The effectiveness of treatment has been reviewed by Trinkley and colleagues.345 They identified 58 placebo-controlled clinical trials of various medications for IBS. They concluded that more studies with better design were necessary, but there was evidence of efficacy depending on the symptoms for the use of loperamide, fiber, selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants, probiotics, octreotide, and antispasmodics.

WILLIAM ARBUTHNOT LANE (1856-1943)

|

Lane was born at Fort George, Inverness, Scotland, the eldest son of a military surgeon. As a youth, Lane moved frequently with his parents—to South Africa, Ceylon, Nova Scotia, Malta, and Ireland. He entered Guy’s Hospital in London in 1872 and achieved his fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1882. Following a period of travel in the Caribbean as a ship’s surgeon, Lane was appointed to the staff of Guy’s Hospital. He quickly became known as a master technician whose operations a patient could be expected to survive. There were three procedures for which he was renowned: the treatment of cleft palate, open reduction and internal fixation of fractures, and the surgical management of “chronic intestinal stasis.” He wrote voluminously (313 articles) and produced a number of short books. During the First World War, Lane was consulting surgeon to the Aldershot Command, in addition to his responsibilities at Guy’s Hospital and at the Hospital for Sick Children (Great Ormond Street). He received a baronetcy in 1913, and in 1917 he was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. At the end of the war, he retired from Guy’s, and shortly thereafter, he extended his views from the hospital to the whole world. In 1925, he founded the New Health Society, an organization dedicated to social concerns in medicine. (Photograph courtesy of Guy’s Hospital, London.)

Chronic Idiopathic Constipation

This is an example of a FGID in which constipation is present but pain is not. However, there must be a considerable overlap with IBS besides the absence of pain. In a meta-analysis conducted by Suares and Ford of 45 articles reporting 261,040 subjects worldwide, the prevalence was estimated to be 14% lower in Southeast Asia.326 It was higher in women (odds ratio [OR] = 2.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.87-2.62) with age, socioeconomic class, and in patients who also fulfilled the criteria for IBS (OR = 7.98; 95% CI, 4.58-13.92).

The large overlap of definitions and discrete clinical groupings of constipation is illustrated by McCallum and colleagues.224 They prefer a more inclusive definition— that is, any patient experiencing persistent difficulty with defecation. This will therefore include most patients with a nonorganic cause.

Slow-Transit Constipation

A large number of diseases, including diabetes and flat feet, are due to autointoxication arising from chronic sepsis in the intestinal cesspool.

—WILLIAM ARBUTHNOT LANE (1900)

In 1908, Lane first offered a surgical alternative to the treatment of chronic constipation.189 After initially performing ileocolonic bypass and then partial colectomy, he reported 38 patients who underwent subtotal colectomy for this complaint. However, it is only since the mid-1980s that publications have appeared to reconfirm the legitimacy of subtotal or total colectomy in the treatment of chronic constipation.

STC occurs almost exclusively in young women. It often starts in childhood or there may be an apparent trigger such as a pelvic operation or an episode of acute constipation.174 The condition is likely to include various functional disorders and should therefore be regarded as a heterogeneous condition.254

The colon generally is of normal caliber, and there is delay in colonic transit as can be demonstrated by radiopaque markers or by scintigraphy.19,155,322 In addition, there

is evidence of low-amplitude propulsive waves of short duration.18 The early postprandial colonic response is absent, and the response to bisacodyl is reduced.155 There is evidence of a reduction of the ICC.122 The results of studies up to the year 2000, which have investigated neuronal morphology, in vitro pharmacologic behavior of colonic smooth muscle, immunocytochemistry of neuronal antigens, and neurotransmitters, have been summarized by Knowles and Martin.174

is evidence of low-amplitude propulsive waves of short duration.18 The early postprandial colonic response is absent, and the response to bisacodyl is reduced.155 There is evidence of a reduction of the ICC.122 The results of studies up to the year 2000, which have investigated neuronal morphology, in vitro pharmacologic behavior of colonic smooth muscle, immunocytochemistry of neuronal antigens, and neurotransmitters, have been summarized by Knowles and Martin.174

Belsey and colleagues conducted a review of reports describing the quality of life in individuals with constipation.27 They identified 13, of which 10 dealt with adults and 3 with children. Using the SF-36 (12 tools), there was consistent impairment of mental and physical domains, greater in the former. The degree of diminution was comparable to that seen in inflammatory bowel disease.

Treatment

Medical

Medical management includes the treatment of any underlying medical disorder and the suspension of constipating medication if this is being taken by the patient. The patient should be given dietary advice, and exercise should be encouraged. The efficacy of many commonly prescribed drugs, such as stool softeners, medications containing senna, and bisacodyl, remains to be defined.224

In a person with an evacuation disorder primarily responsible for symptoms, the condition should be explained, ideally with the use of diagrams. Suppositories may be prescribed to promote a strain-free defecation. Glycerine suppositories have a lubricant effect, but bisacodyl suppositories may be more reliable, owing to their pharmacologic action on the smooth muscle of the rectum. The patient should be exhorted to avoid straining, although this is very difficult to accomplish in practice.

Prucalopride is a selective high-affinity serotonin receptor antagonist, which has been applied to the management of constipation. There have been three controlled double-blinded clinical trials with author overlap, which show improved frequency of defecation and well-being in those taking the drug.44,273,332,367,361 Of 1,974 patients pooled from these studies, more than 85% were female. Bowel frequency assessed at 12 weeks increased from less than two evacuations per week to three or more in the prucalopride group compared with 10% among those taking the placebo. The PAC quality-of-life score was 29% to 49% and 16% to 26% in the prucalopride and placebo groups. Despite these results, it was felt that the drug could not be recommended for constipation, owing to its cost and the incidence of the side effects of nausea, headache, and abdominal pain.367 However, there will be cases so refractory that anything is reasonable to try if tolerated by the patient.

Biofeedback

This behavioral treatment was introduced for the treatment of fecal incontinence (see Chapter 16) but has also been applied to constipation. There is evidence that it is effective in patients with obstructed defecation as opposed to those with STC. In a study of 52 patients with delayed transit, 34 had simultaneous evidence of obstructed defecation.52 Biofeedback improved in 71% of these patients but only in 8% of the 18 individuals with STC alone. Interestingly, colonic transit improved in those in the former group but not in the latter.

Other studies have demonstrated efficacy of biofeedback for the treatment of constipation or evacuation disorders in prospective, often randomized controlled trials.23,53,54,81,128,182,229,276,348,365 Koh and colleagues reviewed the literature on biofeedback for pelvic floor dysfunction.179 They included seven publications, and the authors concluded that high-quality studies were lacking. Despite this, they felt that biofeedback conferred a sixfold chance of successful treatment improvement. Others have published useful reviews on this issue.275

Biofeedback is free of complications and should be advised before any invasive treatment is considered. No trial of neuromodulation or surgical technique should be conducted without the patient having already tried and failed biofeedback.

Neuromodulation

Sacroneuromodilation. Following the report by Matzel and colleagues in 1995 of three patients treated for fecal incontinence by sacroneuromodulation, this approach began to be applied to patients with constipation.10,220,242 Its effectiveness for incontinence and the technique, possible modes of action, and clinical results are described in Chapter 16.

Early reports of sacroneuromodulation for constipation include case reports and small series in which it became clear that some patients responded in the short and some in the intermediate term.84,165,166,212 In a study of 19 patients with constipation, improvement was reported in 42%.134

The most important evaluation of sacroneuromodulation for constipation is the prospective multicenter European trial, which recruited 62 patients who had failed to respond to medical treatment and biofeedback.149 Forty-five exhibited a positive peripheral nerve evaluation and thus went on to permanent implantation. Not only did bowel frequency and symptoms of evacuation difficulty improve, but abdominal symptoms of pain and bloating did also. Thus, the number of days of pain per week experienced by the patient fell from 5 (0-7) to 1.7 (0-7) and those for bloating from 5.7 (0-7) to 2.3 (0-7). The Cleveland Clinic Constipation Score (maximum 30 points) fell from 18 (11-27) to 10 (2-22), and the patients’ visual analogue score rose from 8 (0-100) to 66 (11-100). There were improvements in frequency of defecation from 2.3 (0-20) times per week to 6.6 (1-16), time in the toilet fell from 10.5 (2.4-60) minutes to 5.7 (1-31), and the percentage of successful defecations followed by a sense of incomplete evacuation fell from 71% to 45%.

Several authors have demonstrated an increase in the rate of colonic transit after sacroneuromodulation for severe constipation.66,67 This action is unlikely to be the only factor resulting in the clinical improvement as discussed in Chapter 16. In practice today, a patient who has not responded to medical or behavioral treatment should be considered for neuromodulation before contemplating a more invasive procedure.

Posterior Tibial Neuromodulation. There are now some preliminary data on this form of neuromodulation for constipation. In pilot study of 18 (17 females) patients, twelve 30-minute sessions were given over several weeks. The Cleveland Clinic score fell significantly from 18 (10-24) to 14 (7-22), and the patient assessment of constipation quality-of-life (PAC-QoL) score also improved.60 A modest objective gain may be considered satisfactory by the patient.

Irrigation

Irrigation, either antegrade or retrograde, has also been used for the treatment of both incontinence and constipation. This has been described in Chapter 16. Retrograde irrigation has been made easier for self-administration by the development of closed systems. A rectal balloon can be used (Peristeen anal irrigation system; Coloplast A/S, Kokkedal, Denmark or Mallinckrodt, St. Louis, MO; see Figure 16-23), or a cone-shaped colostomy tip may be employed (Coloplast A/S, Humlebæk, Denmark; Qufora irrigation system; Allerød, Denmark; or Biotrol irrimatic pump; Braun; see Figure 31-25).

Antegrade. Access of antegrade irrigation is achieved via an appendicostomy (see Figure 16-23),185,211,266,290 via a colonic conduit (see Figure 16-24),137 or the sigmoid colon via a percutaneous endoscopic colostomy (PEC).13,61,126,205 Successful medium-term irrigation results with this last procedure were achieved in 73% of 92 patients, but there were serious side effects, including peritonitis in up to 10% of cases. Furthermore, the dropout rate was high. Late erosion with perforation can also occur.

Retrograde. Retrograde irrigation is safer and has achieved “success” in 57% of 113 patients, but again, the dropout rate was high in some reports (ranging from 8% to 70%).48,62,106,177 This has been demonstrated further by Chan and colleagues.50 They reported the outcome of irrigation in 50 of 60 patients with constipation who attended follow-up (83%). Half had stopped irrigating. This was attributed to failure of improvement in symptoms; 7 ultimately underwent some form of surgery. The conclusion from these reports is that irrigation should be discussed with the patient. Retrograde irrigation appears preferable to antegrade, and the patient will need encouragement from the nurse/therapist to persist. The chance of success over 1 to 2 years appears to be about 50%. For those with spinal cord injury or spina bifida, the reader is referred to Chapter 16. The concept of the value of irrigation has also been reviewed by Tod and colleagues.343

Surgery

Since the last edition of this text, the use of surgery for constipation has declined markedly. Whether this is an entirely beneficial occurrence is a matter of debate, but there can be no question that fewer operations for constipation are performed in most units today compared with 10 years ago. To some extent, this is because the intermediate results of surgery are now known. First, there is significant morbidity, especially small bowel obstruction.261,381 Although stool frequency and laxative consumption decrease in approximately 70% of patients, this effect may last for only a few years or less. In addition, about 10% of patients experience frequency, sometimes with urgency incontinence. Moreover, abdominal symptoms, such as pain and bloating, are often not improved, unlike with neuromodulation. Another reason for the reduced application of colectomy is the demonstration of the efficacy in many cases of neuromodulation. In Europe, it has become the first choice for an invasive treatment when the patient continues to be symptomatic despite medical and behavioral treatment.

There has clearly been considerable case selection in the studies reporting the results of surgery. In a series of 228 patients with constipation, 111 (38%) had a normal proctogram.330 Of these, 21 had delayed transit of whom 18 underwent a total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis. Of these patients, 19 had excellent function at 2 years. The authors suggested that using proctography to exclude those with a defecation disorder improved the case selection and the results of surgery. Similar evidence of case selection was apparent in a series of 277 patients (43 subtotal colectomy [STC], 38 colectomy),261 and in another of 403 patients (STC 50, colectomy 50).263 “Success” after colectomy ranged from 80% to 100% in three series, which together included approximately 200 patients.261,263,330 When, however, the duration of follow-up was taken into account, 22 of 44 patients followed for 38 (3 to 168) months had relief of constipation as determined by frequency of defecation, but 6 had some degree of incontinence, 5 were still constipated, 17 had diarrhea, 30 still had pain, and 12 were still taking laxatives.153 In another series of 54 patients followed for 42 months (range, 3 to 81), 6 experienced incontinence, 14 constipation, 2 diarrhea, 27 pain, and 5 continued laxative administration.202 In a recent report from the Cleveland Clinic of 69 patients who underwent colectomy between 1983 and 1998, 11 (16%) developed early and 32 (46%) late complications.381 Thirty-five out of a possible 64 responded to a questionnaire, which showed that abdominal, pelvic, and rectal pain were present in 13, 10, and 11 patients; bloating in 23 (66%); and nausea in 13 (37%). Nevertheless, 27 (77%) expressed satisfaction with the operation, although social function and mental vitality were low. In a report from the Mayo Clinic of 104 patients with STC treated by colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis at a median interval of 11 years previously, data were available on 85.121 Constipation resolved in 98%, and 85% of patients were satisfied. Fifty-nine patients responded to a questionnaire. All reported improved frequency of defecation, and 83% were not taking any medication. The KESS score improved significantly. Restorative proctocolectomy has been used by our unit in highly selected patients.250

In an important paper, Redmond and colleagues used scintigraphy to distinguish between patients with colonic inertia and those with a generalized intestinal motility disorder in which gastric emptying as well as colonic transit was impaired. “Success” after colectomy was reported in 90% of 21 individuals with colonic inertia alone compared with 16% of 16 patients with generalized intestinal dysmotility.279 It appears then that case selection based on proctography and scintigraphy may improve the results of surgery, but there remain disadvantages for the patient. These may have to be accepted in the uncommon individual who continues to have disabling symptoms despite medical, behavioral, and neurostimulatory treatment. The subject has been usefully reviewed by Levitt and colleagues.195

Dilated Bowel

Aganglionosis

Hirschsprung’s Disease. Hirschsprung’s disease was described in 1887 (see Chapter 3).132 It occurs in 1 in 5,000 births and is four times more common in boys than girls. The clinical picture is due to a physiologic intestinal obstruction caused by lack of ganglion cells in the distal large bowel. The affected segment becomes spastic, causing failure of the normal transmission of stool. This results in constipation proximal to the aganglionic segment. This can vary in extent from the lowest part of the rectum (ultrashort segment) to any distance more proximally. Agangliosis of the entire large bowel is very rare; in most cases, the segment does not extend beyond

the rectosigmoid junction. It seems that the spastic segment can also occur above a normal distal rectum. There has been a case report of narrowing at the rectosigmoid junction with dilatation of the colon above and a normal rectum with a normal rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) below.379

the rectosigmoid junction. It seems that the spastic segment can also occur above a normal distal rectum. There has been a case report of narrowing at the rectosigmoid junction with dilatation of the colon above and a normal rectum with a normal rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) below.379

FIGURE 20-12. Short-segment Hirschsprung’s disease is confirmed by the abrupt change in caliber from the normal-appearing distal rectum (arrow) to the dilated proximal bowel. |

In most cases, the diagnosis is made shortly after birth when there is failure to pass meconium in the first 24 to 48 hours of life. Depending on the extent of the aganglionic segment, the infant may be initially treated by repeated digital examination, laxatives, and enemas. If the aganglionic segment is long, medical management is not possible, and relief of obstruction by surgery will be necessary. Sometimes, the disease does not present early but may become apparent in childhood or even in adulthood. Hirschsprung’s disease presenting in infancy is discussed in Chapter 3 (Pediatric Surgical Problems). It is noteworthy, however, that many of those who are treated in infancy continue to have intestinal symptoms into childhood and adult life.139

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree