Fig. 23.1

The position of a quadripolar electrode in the third sacral foramen and the anatomical structures around it

Fig. 23.2

An implanted tined lead broken during the removal procedure

Treatment of complications of SNM should be as follows: (1) in cases of infection at the area of the electrode, removal of the electrode is recommended to avoid major problems; (2) in cases of pain, assess whether it persists after stopping stimulation, and whether it disappears after reprogramming the stimulation; (3) in cases of electrode breakage, which is characterized by loss of efficacy and increased impedance, the electrode must be replaced and the same foramen can be used without any problems.

Contrary to what one might think, a critical step is the removal of the electrode for inefficacy or rupture. The literature describes an important hemorrhagic complication for which the patient was taken to the operating theatre twice for packing at the site of the sacral foramen, transfused, and then discharged after 32 days [10]. There are also many reports of rupture of electrodes that remain in the area of the sacral foramen; this outcome, especially from a medicolegal point of view, could be a major problem because the patient has a foreign object that has been left in the body after the failure of the procedure. This is especially important because an abdominopelvic MRI cannot be performed on these patients. In such cases, it is recommended that the surgical access area is enlarged to try to identify the distal stump of the electrode so that it can be removed. In cases of electrode failure, there are no reports in the literature indicating that it should be removed with a neurosurgical approach.

23.2.3 Bulking Agents, Dynamic Graciloplasty, and Artificial Sphincter

Bulking agents have been shown to have low levels [11] or no morbidity [12]. However, some cases of foreign body granulomas have been described after the use of bulking agents [13]. A risk factor for local complications is the presence of multiple scars from previous surgery, for example for an anal fistula, or the presence of active perineal sepsis, even if it is subclinical. Dynamic graciloplasty (DGP) has a very high morbidity rate (69%) [14]; revision surgery, involving the removal of electrodes and implantable pulse generator, is necessary in around 22% of patients. In the use of an artificial bowel sphincter (ABS), removal of the device because of ulcers, sepsis, or ineffectiveness occurs at rates ranging from 37% [15] to 46% [16].

When taking these points into consideration, we believe that DGP or ABS should be considered as rescue procedures, and proposed only to patients that have no surgical options other than a permanent stoma.

23.3 Obstructed Defecation

23.3.1 Stapled Transanal Rectal Resection

Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) is the most talked-about technique that has been proposed in recent years, because of its revolutionary etiopathogenetic aspects and also because of commercial support. The liveliness of discussions on STARR in scientific circles has led to a increase in knowledge about the procedure. Unfortunately, in the world of the coloproctologist, there are those who see only advantages and good results for the procedure, and those who see only complications. The surgeon should be able to appreciate the excellent results produced by the technique and work out how to reduce possible complications. The complications of STARR are discussed below.

23.3.1.1 Anal Pain

To prevent anal pain, patients who have preoperative symptoms of anal or perineal pain should not be subjected to the procedure. Pain is not a typical symptom of rectocele or prolapse, therefore it is risky to operate on a pelvic floor that has an unknown or other source of pain because this procedure will possibly aggravate it.

If the patient still has significant pain 3 or 4 weeks after the operation, especially if it is on the suture line and the pain was not present before surgery, the cause is most likely due to the staples or the hemostatic stitches, which have probably involved, even if only superficially, the underlying musculature. It should be remembered that the correct level for the sutures is usually at the height of the puborectalis sling and if this involves the underlying muscle or if there is excessive fibrosis under the suture it could fix the rectum to the floor below. If this happens, the typical continuous pain is made worse by defecation. The surgeon must be able to recognize if the cause of the patient’s problem is the surgical procedure itself, and must therefore endeavor to resolve it.

Our approach in cases of pain on the suture line is aggressive, with reintervention and removal of most of the suture line, in particular the part of the suture that is most sore and which generally corresponds to the least mobile zones on the underlying tissues.

The continuity of the mucosa should be restored by suturing with absorbable stitches. In our experience (18 cases that have not yet been published), we were able to achieve complete pain resolution in more than 75% of patients using this treatment. This percentage is reduced to less than 48% if the same procedure is performed more than 2 months later. It is essential to make sure that the pain does not become chronic. In clinical practice, we have not found any benefits in the treatment of chronic pain by removing of only some of the staples, as has been described by other authors [17].

In the first few weeks after surgery, if the patient reports that the anal pain is resistant to standard analgesic therapy, the use of neuromodulation drugs such as pregabalin or gabapentin may be helpful. It might also be helpful to consult an anesthesiologist who specializes specifically in the treatment of pain. In our experience [18], which is different from other authors [9], we have had only a few good results in the treatment of pain with SNM after a STARR procedure. We judge a medical failure to be the need for a permanent SNM implantation for pain after the surgical procedure.

23.3.1.2 Anal stenosis

To prevent anal stenosis, avoid sutures that are clearly too low, as well those that are clearly too high. High sutures predispose to stenosis, causing a rectal hourglass shape, and this stenosis interferes with the dynamics of feces expulsion. In practice, the suture level should always fall just above the apex of the hemorrhoidal tissue.

In our experience, we have used all types of staplers available on the market to perform STARR. Stenosis has been found to occur using all types of staplers, including the CCS-30. A trigger for stenosis can be the presence of preoperative proctitis or the occurrence of diarrhea with tenesmus after surgery. The type of staples used might be another factor to take into account: when comparing staples made of pure titanium with those made with titanium alloy, the majority of inflammatory responses were found to be to the alloy [19].

Since anal stenosis is a mechanical anastomosis, it is extremely rigid and does not respond to dilatations with anal dilators or pneumatic endoscopic dilations.

For treatment of anal stenosis, it is advisable to operate again and remove as much as possible of the suture line. Following this, it is necessary to maintain the caliber with mechanical dilatation in combination with transanal mesalazine.

23.3.1.3 Pararectal Hematoma

This is a very dangerous condition because it can also be the cause of further complications such as anastomotic dehiscence, delayed bleeding, or perineal sepsis, which are all equally serious complaints.

Prevention involves the correct choice of and use of the stapler. Because of the full thickness of the anastomosis, it will always include a large amount of mesorectum, and for this reason it is essential to use staplers with correct capacity. Although there have been no complications reported in the literature [20], we consider it extremely risky and wrong to use a stapler with a locking mechanism in the range 0.75–1.5 mm to perform a full-thickness rectal resection. The problem is not with the intraluminal tissues, but with the extraluminal tissues. Also the continuity and speed of the closing action of the stapler should be observed carefully; an unstable closure (a two-step closure) may cause the blade to damage the tissue before complete closure of the staples. This can result in an incomplete suture.

There are no reports in the literature on treatment for pararectal hematomas. Our approach toward this type of complication comes from years of experience and from discussion with coloproctologist colleagues who believe and encourage this type of technique (what type of technique?), while continuing their efforts to overcome possible complications. It is important to differentiate between stable hematoma and active hematoma in patients who are hemodynamically unstable [21].

23.3.1.4 Stable Hematoma

This should be treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, total parenteral nutrition, and spontaneous drainage, which is normal for a minimum suture dehiscence in the third/fourth day after surgery, with gradual drainage of the hematoma cavity. If symptoms such as abdominal pain or failure of bowel canalization persist 3–4 days after surgery, it can indicate the need to perform a minimum transanastomotical opening by the transanal route so as to permit spontaneous drainage. It is important not to drain the hematoma too early, or debride and clean the cavity by washing it with antiseptic solution. Hematomas are usually very large and come up to the rectal peritoneum, and often produce an inflammatory reaction with the appearance of free fluid in the abdomen. Emptying the cavity means risking the rectal lumen coming in contact the peritoneum, a source of bacterial contamination. The presence of air in the hematoma and in the perirectal fat is due mostly to the passage of air from the rectum to the dehiscence, and not to gas gangrene, which would result in more severe symptoms. Our advice is to put a soft drainage tube into the rectum to allow the spontaneous outflow of air.

23.3.1.5 Progressive Hematoma

In cases of progressive hematoma, wait, if possible, for stabilization of the framework through transfusions of blood and plasma. In our experience, derived from emergency surgery, the majority of retroperitoneal hematomas resolve themselves. Embolization by use of angiography is recommended and is efficient for those patients with unstable hemodynamics (Fig. 23.3). In women, it could be useful to use a gauze laparotomy packing through the vagina, associated with the positioning of the Sangstaken-Blakemore probe in the rectum. An aggressive laparotomy should be the very last resort, because, in the presence of a large hematoma, it is impossible to perform dissections that lead to selective hemostasis, and it might then be necessary to resort to a major procedure such as Hartmann’s resection.

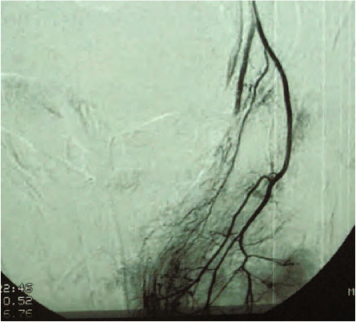

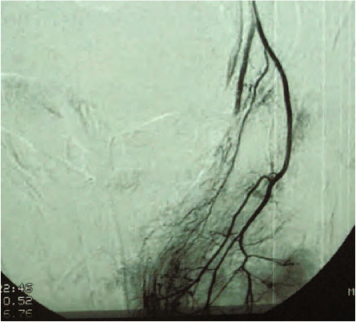

Fig. 23.3

Angiographic embolization for an unstable pelvic-perirectal hematoma

23.3.1.6 Rectovaginal Fistula

This is a technical error that should be avoided if possible.

In order to prevent the occurrence of a rectovaginal fistula, the correct positioning of a vaginal valve is necessary at the beginning of the procedure, so as to support the cervix, vaginal vault, and possible enterocele; the positioning of this valve stretches the rectum and the retrovaginal septum, which become more visible and can be checked easily with a digital maneuver.

In our opinion, it is unlikely to consider a rectovaginal fistula as being secondary to a hematoma drainage, considering the solidity of vagina wall. We think that a hematoma in this area would drain more easily through the rectal anastomosis rather than into the vagina.

Treatment of a rectovaginal fistula is not as simple as it is reported to be in the literature. The preparation of the reconstruction usually leads to a large gap because all of the staples must be removed in the area where the rectum will be repaired. In our opinion, it is extremely difficult to be able to mobilize a rectal flap that is adequate after a STARR procedure that has resected at least 5–10 cm from the rectum. In large resections using CCS-30 (Transtar), the risk is to involve the pouch of Douglas in the suture; for this reason, during the isolation of the anastomosis there is a risk of entering the peritoneum with problems of bacterial contamination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree