Colorectal Trauma

Robert W. Beart Jr.

George C. Velmahos

The profession of medicine and surgery must always rank as the most noble that men can adopt. The spectacle of a doctor in action among soldiers, in equal danger and with equal courage, saving life where all others are taking it, allaying pain where all others are causing it, is one which must always seem glorious, whether to God or man. It is impossible to imagine any situation from which a human being might better leave this world and embark on the hazards of the unknown.

— WINSTON S. CHURCHILL:

The Story of the Malakand Field Force

Hippocrates regarded abdominal wounds as deadly while Celsus advised that their cure be left to nature.30 The injury may be caused by blunt or penetrating trauma of the abdomen or perineum. It may result in damage to the intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal bowel, or it may interrupt its blood supply. If the trauma is to the rectum or perineum, the sphincter mechanism may be injured, as may adjacent organs (e.g., bladder, urethra, and vagina).

The colon is involved in 25% of gunshot wounds, 5% of stab wounds, and 2% of blunt abdominal injuries.104 It is expected that this will continue to be a pervasive problem in our society because of the frequency of motor vehicle accidents and the ready availability of firearms, especially in the United States. There still remains considerable controversy concerning the appropriate management of colorectal injuries. Many of the issues, such as the method of repair for simple colon injuries, have been resolved. Other concerns, such as the role of colostomy in extraperitoneal rectal injuries, have not reached consensus. This chapter will describe the options for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal injuries.

▶ HISTORY

The first recorded injury to the colon was described in the Old Testament in the book of Judges. For centuries, such injuries were untreatable and virtually always resulted in the victim’s demise. The first instance of a successful repair of a musket ball injury to the colon was performed in 1831 by Lucien Baudens, a French military surgeon in Algeria.5 Baudens digitally explored the wound and felt a loop of intestine seemingly hardened by the marked contraction of its muscle coat. Upon pulling his finger out, Baudens noticed that it was covered with feces. He enlarged the abdominal wound and asked the patient to cough. This resulted in a large expulsion of gas from within the peritoneal cavity and caused the injured segment of colon to protrude. The large intestine was noted to have a large, tangential laceration that he repaired with the use of Lembert sutures. The colon was replaced in the abdomen, the abdomen was closed, and the patient recovered.

During the American Civil War, penetrating abdominal injuries were treated nonoperatively and were thus associated with a 90% mortality rate. The decision about nonoperative intervention was made simply because such injuries were virtually always fatal, regardless of the method of treatment. Furthermore, such a noninterventionist approach was probably based on the fact that surgeons at that time had no good idea of what to do when confronted with such a problem. One of the earliest operations for a gunshot wound of the abdomen in the United States was performed by William Bull.

Encouraged by the success of elective surgery following the introduction of anesthesia and of aseptic surgical technique, World War I surgeons began to operate on casualties suffering from abdominal wounds. The standard at that time was primary repair, a considerable improvement over nonoperative management, but the mortality rate was 60%.

WILLIAM TILLINGHAST BULL (1849-1909)

|

William Bull was born in Newport, Rhode Island, a direct descendent of Henry Bull, one of the nine original settlers of Aquidneck and twice governor of the colony. He graduated with honors from Harvard College in 1869 and attended the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York where he received the degree of doctor of medicine in 1872. After completing an internship at Bellevue Hospital, Dr. Bull travelled to Europe where he spent 2 years. He studied surgical pathology in Germany and learned operative technique in France. On his return in 1875, Bull became house surgeon to the New York Dispensary, and in 1876 he was appointed surgeon-in-chief to the Chambers Street Hospital (House of Relief, Department of New York Hospital), a position which he held for 11 years. There he performed one of the earliest laparotomies for abdominal gunshot wound. Prior to his intervention such injuries had been almost uniformly fatal, and his surgery greatly reduced the mortality. In 1880 to 1883, Dr. Bull became assistant demonstrator of anatomy and adjunct professor of surgery. In 1888, he was appointed professor of the practice of surgery and clinical surgery at the College of Physicians and Surgeons. He was also visiting surgeon to the St. Luke’s Hospital and attending surgeon to the New York Hospital. He later served as an attending surgeon at Roosevelt Hospital, the New York Cancer Hospital, and many others. William Bull died in his 60th year of cancer of the neck. (Leonardo RA. Lives of Master Surgeons. New York, NY: Froben Press; 1948; with appreciation to Julia Zakhaleva, MD.)

With the advent of World War II came weapons with a much greater potential for creating massive intestinal injury. Primary repair resulted in a prohibitively high rate of sepsis and death. As a consequence, Major General W. Heneage Ogilvie (see Biography, Chapter 20), senior surgical consultant for the British forces in the North African theater, mandated in 1942 that all colonic injuries should be exteriorized or treated with concomitant colostomies.87 In 1943, the surgeon general of the American forces in North Africa adopted the same policy.86 This succeeded in lowering the mortality rate from colonic injury to 35%.

During the Korean conflict and the war in Vietnam, the mortality rate for colonic injuries was reduced still further to 15% and 10%, respectively. This was largely attributed to the institution of a rapid evacuation system through the use of helicopters, the immediate availability of antibiotics and blood products, and the improvement in methods of resuscitation. There was concern, however, about excessive reliance on modern medical technology in that it appeared to lead to some reports of disastrous results. This led to the call for a return to a more “conservative” approach in the management of intestinal war injuries.

Following World War II, the combat-trained surgeon returned to civilian life and began to apply the principles of management that had been used for colon injuries experienced in warfare (Figure 17-1). Exteriorization of the injured segment, as well as the use of colostomy, became the standard treatment for all colorectal injuries. However, some began to consider that for civilian injuries, typically produced by low-velocity missiles, primary repair could be an appropriate alternative. Numerous studies since the mid-1970s have demonstrated repeatedly that this form of treatment in selective instances is safe.

Today in the United States, a victim of penetrating abdominal trauma is frequently transported to the hospital within a few minutes following injury. Sophisticated radiographic equipment is readily available, as well as intravenous fluids, blood, blood products, and antibiotics. Evaluation by trauma teams and transfer to the operating room is rapid. Under these conditions, it is little wonder that the mortality rate for civilian colorectal injuries is now less than 5%.

A singular advance in the management of individuals with colonic injuries was made by Stone and Fabian in their 1979 publication in which they conducted a randomized trial of patients meeting so-called good-risk criteria.112 Patients with colonic injuries who were believed to be good risks were randomly allocated to either undergo a primary repair or a colostomy. Fewer septic complications were observed in the former group. This study succeeded in inspiring others to implement primary repair more frequently. Numerous articles have since been published demonstrating the efficacy of primary repair, especially as applied to civilian trauma centers in the United States.1,4,11,20,22,28,31,38,40,42,43 and 44,47,54,55,56,61,62,69,73,81,83,98,103,105,113,115,127,132

This trend continued in the 1990s, with numerous contributors advocating primary repair as the objective of management for both civilian and wartime colon injuries.10,12,13,24,26,64,82,96,102 Furthermore, anastomotic failure rates have been quite low, reinforcing the fact that primary repair, at least today, is the ideal approach for the treatment of colonic injury.

▶ ETIOLOGY AND EVALUATION

Penetrating Trauma

Most colon injuries result from penetrating wounds to the abdomen. Twenty percent of all such wounds are associated with injury to the large bowel. Septic morbidity is a real danger because of the combination of fecal spillage, soft tissue injury, and bleeding, all of which predispose to subsequent infection. Furthermore, gunshot wounds of the colon are typically associated with more tissue destruction and result in an increased number of associated injuries in comparison with stab wounds (Figures 17-2,17-3,17-4,17-5,17-6 and 17-7).

With respect to etiology, it is generally self-evident as to the nature of the causative agent when one is confronted with a penetrating injury to the abdomen. However, how one proceeds with evaluation and treatment is subject to some controversy. Stab wounds of the abdomen, which more than 20 years ago were frequently managed by routine laparotomy, are now subjected to selective nonoperative management. Only patients with diffuse abdominal tenderness or hemodynamic instability are rushed to the operating room. All other patients who can be reliably evaluated should be monitored closely and observed for the development of abdominal signs. For abdominal gunshot wounds, the tendency to treat by means of laparotomy is much more frequent. Based on reports of a high incidence of intraperitoneal organ injury after a gunshot wound to the abdomen and on the relatively “benign” consequences of a negative laparotomy, many surgeons operated routinely with this presentation. However, the frequency of significant abdominal injuries has been found to be approximately 70%, and the incidence of complications following a negative exploration ranges from 20% to 40%.29,119,121,122,124,125 Therefore, a policy of selective nonoperative management for abdominal gunshot wound may be as prudent as it is for stab wounds. In the largest study to date, that of 1,856 abdominal gunshot wounds, 34% of the anterior and 68% of the posterior abdominal injuries were selected for nonoperative management.125 The rate of nontherapeutic laparotomy was 9%. Of complications related to nonoperative management (0.3%, five cases), all were treated successfully. The concept of selective nonoperative management was applied to different populations and found to be equally valid.122,123 and 124

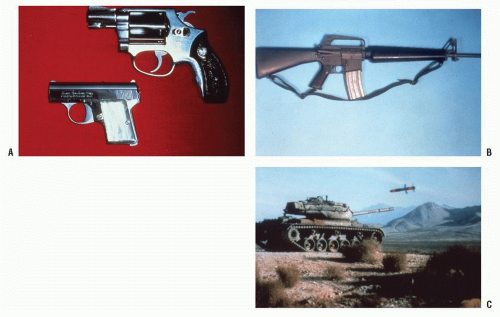

FIGURE 17-1. Progressively more destructive penetrating wounds depend on the velocity and the mass of the projectile. A: Bad. B: Worse. C: Worst. (Courtesy of Daniel Rosenthal, MD.) |

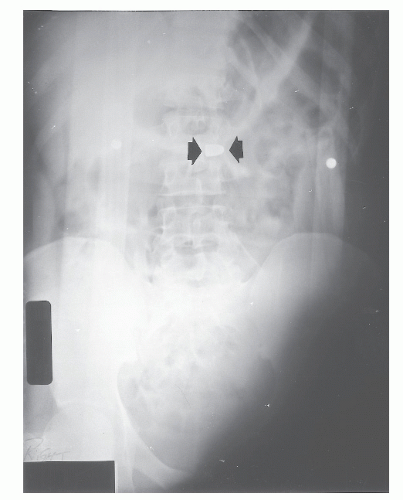

FIGURE 17-3. Bullet wound of the abdomen. The missile can be seen overlying the vertebra (arrows). The missile traversed the transverse colon and the aorta. The patient survived this injury. |

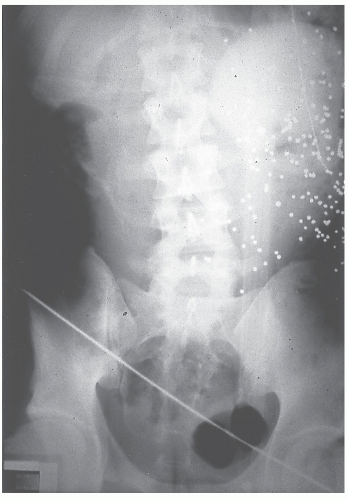

FIGURE 17-4. Metallic fragments overlying the right ilium imply that the missile struck bone. The distal small bowel and right colon were virtually vaporized. |

FIGURE 17-5. A similar injury was created from this bullet wound to that noted in Figure 17-3. However, note that the ilium was shattered. The patient also suffered major vessel injury to the right leg. |

FIGURE 17-6. This bullet traversed the small bowel, the transverse colon, and the vena cava. The entrance wound is marked by a safety pin. |

Laparoscopy

The use of laparoscopy has also been suggested for the evaluation of patients with penetrating abdominal trauma.33,36,53,63,99,106,108,109,136 In stable individuals, laparoscopy is a highly sensitive test for determining peritoneal penetration. It can be particularly helpful for thoracoabdominal wounds when local exploration may not be possible or may actually be contraindicated. Laparoscopy is sensitive for detecting a diaphragmatic injury, a situation in which observation, diagnostic peritoneal lavage, or focused sonography may be unhelpful.76 Although laparoscopy is sensitive for determining peritoneal penetration, it should be noted that this technique is not nearly as reliable for identifying intra-abdominal injury. Retroperitoneal or hollow viscus injuries can be missed with laparoscopic exploration. Furthermore, the benefit of repeated clinical examinations to detect evolving tenderness is lost for an individual postlaparoscopy. Most investigators have cautioned against using laparoscopy for purposes other than determining peritoneal penetration. However, given the fact that peritoneal penetration in itself should not constitute an absolute criterion for laparotomy, the role of diagnostic laparoscopy is still indeterminate. In summary, laparoscopy is useful in determining whether diaphragmatic injuries have occurred in hemodynamically stable patients with thoracoabdominal penetrating injuries and who do not have other reasons for surgical exploration.

Computed Tomography and Focused Abdominal Sonographic Assessment

Focused abdominal sonographic assessment for trauma (FAST) and high-resolution computed tomography (CT) have both been employed as adjunctive techniques to that of clinical assessment of the abdomen following penetrating trauma. These procedures may be useful in the decisionmaking process with respect to the advisability of operative versus nonoperative intervention in stable patients with penetrating wounds.16,118 Although CT is frequently used in patients who do not require immediate exploration, there is still debate about its sensitivity and specificity.119 FAST appears more useful in blunt trauma. Because penetrating injury may occur without an associated large volume of free fluid within the abdominal cavity, the sensitivity of FAST is low in this circumstance.70

Blunt Trauma

Blunt trauma to the abdomen causes colonic injury in fewer than 5% of these cases. Mobile segments of the colon (e.g., cecum, transverse colon, and sigmoid colon) are more susceptible to injury, although other areas of the bowel can be affected. Most perforations are found in the sigmoid colon, an observation that can be explained by its redundancy, its tendency to form a closed loop, and/or to be subjected to acceleration/deceleration forces. The right side of the colon, however, is the most common site for devascularizing injuries.21 These patients are usually victims of motor vehicle accidents and therefore commonly have multisystem and multiorgan injuries (Figures 17-8 and 17-9).14,21 The use of seat belts seems to be a predisposing factor.2,7,48,92 Appleby and Nagy caution that a high degree of suspicion should be maintained in individuals who are found to have bruising of the abdominal wall as a consequence of the use of seat belts.2 These individuals have a high incidence of gastrointestinal injuries and, in addition, associated lumbar spinal injuries.

Bubenik and colleagues describe three patients who sustained blunt colonic injury.9 In their experience, a characteristic scenario was observed. Perforation was discovered 7 to 10 days following the incident, indicated by findings suggestive

of sepsis. A particularly prominent sign of occult infection was the syndrome of posttraumatic pulmonary insufficiency.

of sepsis. A particularly prominent sign of occult infection was the syndrome of posttraumatic pulmonary insufficiency.

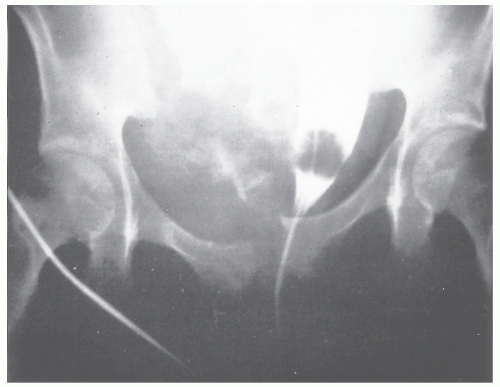

FIGURE 17-8. Motor vehicle accident causing severe blunt trauma resulted in a displaced pelvic fracture. The patient sustained bladder injury as well as major trauma to the sigmoid colon. |

Wisner and coworkers identified 56 individuals who sustained blunt intestinal injury, but only 6 of these were colonic.133 Most injuries occurred in the proximal and distal small bowel at points of fixation, with devascularization most frequently seen in the ileum and in the sigmoid colon. The same principles of treatment as those discussed with respect to penetrating injuries apply here, but the authors caution that delay in diagnosis is one of the major concerns. They note that CT was not especially helpful in the preoperative assessment, but this may have improved with advancements in CT technology.

Howell and colleagues identified 19 patients who sustained blunt trauma to the colon.49 They advise that careful inspection of pericolic, subserosal, and mesenteric hematomas at the time of laparotomy is essential for the detection and management of such injuries. Unfortunately, some individuals present many days following the initial injury and are found on exploratory laparotomy to have considerable contamination and sepsis. Under these circumstances, resection and a diversionary procedure are indicated. As with other types of colonic trauma, infections are the major source of morbidity, but the nature of associated injuries is the principal determinant of survival.49

FIGURE 17-9. Mesenteric rent in the small bowel from blunt trauma as a consequence of a motor vehicle accident. |

Diagnosis

Fortunately, blunt trauma to the abdomen rarely produces injury to the colon. However, when it occurs, the consequences can be devastating. Alterations in the patient’s level of consciousness, as well as the presence of associated injuries, present problems in diagnosis and therapeutic priorities. Peritoneal lavage, CT of the abdomen, and abdominal ultrasonography have been described as adjunctive measures for evaluating patients with such injuries. Peritoneal lavage may be useful if the returns are grossly positive with stool, but frankly this is an antiquated approach. The risk of oversensitivity by which a lavage is deemed positive even with a minimal amount of free blood has been the main reason for abandoning this technique. In most modern trauma centers, CT has almost exclusively replaced peritoneal lavage. It is readily available, and it avoids the risk associated with intervention-related complications.

The results of CT may be difficult to interpret. Certainly, the presence of free fluid without evident liver or spleen injury is worrisome, as is the presence of mesenteric inflammatory change, edema, or hematoma. Free air is a pathognomonic sign of hollow visceral injuries.

FAST will not detect an injury to the colon unless sufficient fluid or blood is present. Still, McElveen and Collin found an overall sensitivity of 88% and a 98% specificity when comparing this test with others in individuals with blunt abdominal trauma.67 FAST is quite helpful when it is positive; the reported specificity rate is high for detecting hemoperitoneum (in the range of 95% to 100%).77,91 When the ultrasound scan is negative, the results are not as beneficial; the reported specificity rates range from 42% to 87%. The wide discrepancy in sensitivity and specificity serves to

emphasize another potential weakness of the ultrasound examination—that is, operator dependency. Taking this into consideration, the FAST examination is a useful adjunct for abdominal assessment during resuscitation for trauma. It is most helpful in patients with hemodynamic instability and in those who cannot readily be moved to the CT scanner.

emphasize another potential weakness of the ultrasound examination—that is, operator dependency. Taking this into consideration, the FAST examination is a useful adjunct for abdominal assessment during resuscitation for trauma. It is most helpful in patients with hemodynamic instability and in those who cannot readily be moved to the CT scanner.

A large volume of literature supports the use of CT for patient assessment following abdominal trauma.68 CT scan has been shown to be highly sensitive and specific. However, the Achilles heel of CT scanning has been the presence of a mesenteric tear or an early hollow viscus injury. Still, the newer generation of CT scanners is more sensitive than prior technology, but such injuries can still be missed. A high degree of suspicion with appropriate clinical correlation improves the overall accuracy. Additional signs of colon or small bowel injury include mesenteric hematoma; edema; bowel wall thickening; and, as mentioned, the presence of free fluid without evident solid organ injury. Nolan and colleagues opine that physicians should entertain the possibility of mesenteric injury in all patients presenting with blunt abdominal trauma, even if few clinical findings are initially present and/or CT fails to demonstrate a definitive abnormality or injury.85

▶ SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

General Principles

Once the decision has been made to perform an exploratory laparotomy, the abdomen is entered through a midline incision. It is important to preserve the area overlying the rectus muscles in case a stoma is required. Initial efforts are directed toward identifying and controlling any source of bleeding. An attempt should be made to contain spillage of intestinal contents by means of atraumatic clamps and sponges. Following the control of hemorrhage and sources of contamination, a thorough search is made for all possible sites of injury. The entire gastrointestinal tract and mesentery are carefully inspected. Special attention should be given to the number and location of all wounds. Usually, there is an even number of openings in the bowel, compatible with a typical through-and-through injury pattern. However, when an odd number of wounds is identified, the surgeon should make a great effort to look for the “missing hole.” The bowel should be carefully reinspected, especially the region adjacent to the mesentery, where breaches of the bowel wall may be hidden. It is suggested that the entire gastrointestinal tract be inspected twice, even when all wounds appear to be accounted for. Obviously, a missed visceral injury can have catastrophic consequences.

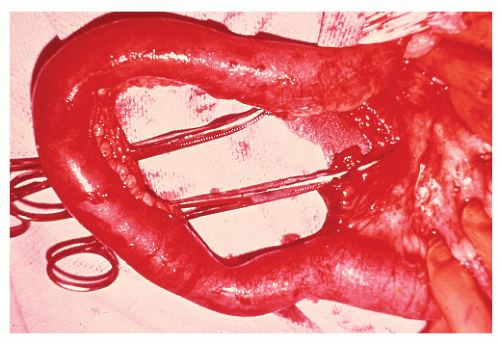

Once the injuries have been identified, the surgeon then proceeds with the repair. When primary repair is attempted, care must be taken to avoid narrowing the lumen; therefore, this is often accomplished in a transverse fashion (Figure 17-10). Whether a two-layer or a single-layer technique is employed is a matter of each individual surgeon’s personal preference. When the colon is destroyed or its blood supply is compromised, resection is mandatory (Figure 17-11). If diversion of the fecal stream is required, either the injured segment is brought out to the abdominal wall or a proximal portion of bowel is selected as a

colostomy or ileostomy. Meticulous attention should be given to creating a satisfactory stoma; some reports have suggested that complication rates for stomal construction in conditions of trauma are higher than those reported for elective surgery.90,107,135 This may be attributed to the fact that sufficient attention is not paid to the creation of a satisfactory stoma when the surgeon is dealing with an emergency problem in a critically ill patient. It is often suggested that the skin wound be left open or sutures placed for delayed primary repair, although this remains a subject of controversy. Wound infections range from a relatively minor problem to a serious event, leading to a fascial dehiscence, to a potentially life-threatening complication, and to necrotizing soft tissue infections.128 The presence of concomitant shock, soft tissue injury, and fecal contamination creates an environment unlike that of elective colon surgery, one that may encourage the development of overwhelming sepsis.

colostomy or ileostomy. Meticulous attention should be given to creating a satisfactory stoma; some reports have suggested that complication rates for stomal construction in conditions of trauma are higher than those reported for elective surgery.90,107,135 This may be attributed to the fact that sufficient attention is not paid to the creation of a satisfactory stoma when the surgeon is dealing with an emergency problem in a critically ill patient. It is often suggested that the skin wound be left open or sutures placed for delayed primary repair, although this remains a subject of controversy. Wound infections range from a relatively minor problem to a serious event, leading to a fascial dehiscence, to a potentially life-threatening complication, and to necrotizing soft tissue infections.128 The presence of concomitant shock, soft tissue injury, and fecal contamination creates an environment unlike that of elective colon surgery, one that may encourage the development of overwhelming sepsis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree