Chapter 36 Colonoscopic Polypectomy, Mucosal Resection, and Submucosal Dissection

Introduction

A new wave of change in the field of colorectal neoplasms and colonoscopy is here, leading to the work in colonoscopic resection to begin anew. Nonpolypoid colorectal neoplasms (NP-CRN) are now widely recognized in Western countries (Fig. 36.1).1 This finding requires numerous paradigm shifts in our clinical, educational, and research activities. The detection and diagnosis of NP-CRN necessitates the search for subtle nonprotruding findings during colonoscopy.2 Treatment of NP-CRN requires mucosal resection technique, which is more complex than polypectomy. Because nonpolypoid neoplasms can be found throughout the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, all endoscopists must become familiar with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) techniques, and future generations must understand its theoretical basis, obtain the dexterity to perform it, and perfect it. Knowledge about the biology and outcomes of the management of nonpolypoid GI neoplasms is to be acquired. Within the same period of time, new technology—high definition, high magnification, and image-enhanced endoscopy3—that is useful for the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of NP-CRN has become available and is increasingly employed. The technique of submucosal dissection, which has become a standard resection technique for early gastric cancer in Japan, is also being applied for the resection of certain types of colorectal neoplasms to achieve R0 resection—curative en bloc resection with all margins being free of neoplasms (Fig. 36.2)4—without surgery.

Advances in the ability to detect, diagnose, and treat all types of colorectal neoplasms are important. These advances provide hope that the benefit of colonoscopy screening to prevent colorectal cancer, one of the most common causes of cancer death worldwide, can be extended further. In the United States, it was estimated that there would be approximately 146,970 new cases of colorectal cancer in 2009 and 49,920 deaths caused by the disease. The lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer in the U.S. population is about 6%, with 90% of cases occurring in individuals older than 50 years. The U.S. incidence of colorectal cancer is slightly higher in men than in women, but because women live longer than men, the total number of cases is higher in women. Colorectal cancer incidence and mortality also vary by race and ethnicity, with the highest rate occurring in African Americans; an intermediate rate occurring in whites and Asian/Pacific Islanders; and the lowest rates occurring in American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Hispanics.5 Most colorectal cancer deaths are believed to be preventable with screening colonoscopy and polypectomy.6 The paradigm that a significant majority of colorectal cancers are thought to arise through the adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence7 has been expanded with mismatch repair, serrated, and hybrid pathways.8

Neoplasms can be both polypoid and nonpolypoid, and NP-CRN has a higher risk to contain high-grade dysplasia or submucosal invasion at the time of colonoscopy compared with polypoid neoplasm.1,9,10 It has been estimated that 25% to 40% of adults older than 50 years in the United States have at least one adenoma and that a small fraction of these adenomas progresses to cancer. Because it is impossible to predict which adenoma will become malignant, physicians attempt to remove all adenomas during colonoscopy. The National Polyp Study, which showed that removal of adenomas during screening colonoscopy can decrease the subsequent development of colorectal cancer by 90% compared with historical controls, provided a level of support to this current standard of practice.6 It is our dream to be able to prevent the development of advanced cancer safely and efficaciously in every patient we treat.

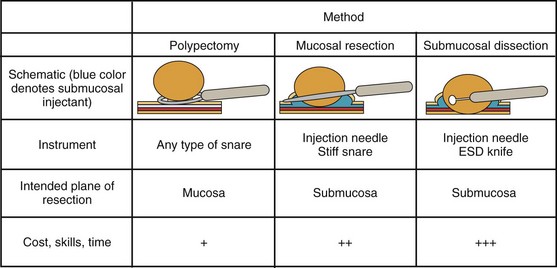

Endoscopically, adenomas and early colorectal cancer can be classified as polypoid (protruded) and nonpolypoid (superficial) types (Fig. 36.3).11 Colonoscopic polypectomy can be used to remove polypoid lesions. Colonoscopic mucosal resection, using the inject and cut technique, is a safe and efficacious technique used to remove nonpolypoid or sessile lesions. Colonoscopic submucosal dissection technique, which is used to remove diseased mucosa by dissecting through the middle to deeper layers of the submucosa, can refine our ability to remove lesions that are difficult, if not impossible, to remove using mucosal resection technique. In this chapter, we provide an in-depth survey of colonoscopic resection of polypoid and nonpolypoid colorectal lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

Careful endoscopic observation of the surface features of the lesion can often allow differentiation of epithelial from nonepithelial origin because nonepithelial lesions are usually covered by normal mucosa. With current videocolonoscopes, and especially with the addition of image enhancement and magnification endoscopy,12 it is increasingly possible to distinguish reliably among hyperplastic polyps, adenomatous polyps, and superficial early adenocarcinomas. Colonoscopic resection may be viewed as a diagnostic procedure. Removal of the entire lesion, when possible, provides the most rigorous evidence that a malignancy was not missed, as it might be because of sampling error with standard biopsies. These procedures provide the definitive treatment when the lesions are removed completely. Subepithelial lesions sometimes can be removed safely when they are located above the muscularis propria, as evidenced by their endoscopic appearance, response to submucosal saline injection, and, if needed, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). Generally, biopsy should be performed if possible in lesions that are not amendable to endoscopic resection to ascertain their histology, and the lesions should be endoscopically marked for surgical planning with submucosal tattoo and radiopaque clips.

Clinical Features and Pathology

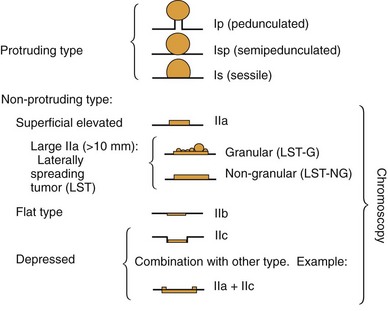

The macroscopic classification of adenomas and early colorectal neoplasms is crucial in the discussion of diagnosis and treatment of early colorectal cancer.11,13 The classification by the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum can provide a common descriptor of adenomas and early colorectal cancer (mucosal or submucosal cancer, regardless of lymph node status). The Paris classification has been promoted for worldwide use14—although a derivative from the Japanese categorization, its slight alterations in morphologic definitions make it difficult to infer directly the knowledge that has been meticulously collected by our Japanese colleagues. The application of a standard classification of colorectal lesions is the first step in stratifying which lesions are more likely to contain advanced pathology.

Based on their endoscopic appearance, we classify adenomas and early colorectal cancers as polypoid and nonpolypoid. The polypoid type consists of pedunculated, semipedunculated, and sessile polyps. The nonpolypoid type consists of superficially elevated, flat, and depressed lesions. Excavated superficial colorectal neoplasms are rarely observed. Superficially elevated nonpolypoid lesions are differentiated from sessile polypoid lesions both endoscopically (the height of the lesion is less than half the diameter) and histologically (the thickness of the lesion is less than twice that of the adjacent normal mucosa).15 The term flat is often used to describe superficially elevated lesions. In the colon, however, flat generally connotes that the surface is flat, rather than that the lesion is at the same level as the surrounding mucosa (in the colon and rectum, in contrast to in the esophagus, early neoplastic lesions are rarely at the same level as the surrounding mucosa.)

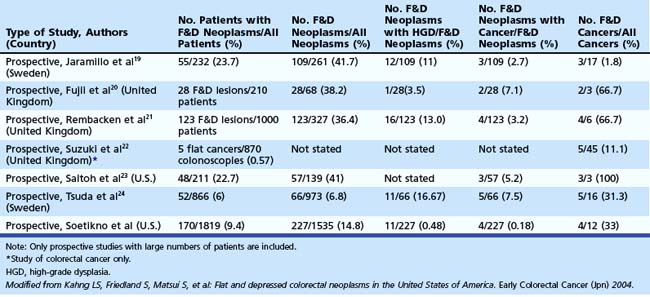

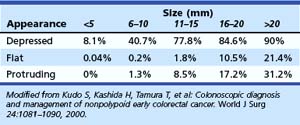

In the Japanese literature and increasingly becoming common worldwide, flat lesions (IIa) larger than 10 mm are also called laterally spreading tumors (LST), although the term refers more to the growth pattern rather than the endoscopic appearance. In the United States, these large flat lesions are often called carpet lesions. LST with nodular or coarsely granular surfaces are called LST-granular. Other LST are called LST-nongranular. This distinction is important because LST-nongranular are more likely to contain invasive cancer, which is more difficult to assess endoscopically. LST-nongranular are also more difficult to resect and may require en bloc resection to ensure cure. In the Paris classification, semipedunculated lesions are lumped into the pedunculated category, and flat lesions are defined as lesions with height less than a closed biopsy forceps. Depressed nonpolypoid lesions, although rare, accounted for almost one-third of the invasive early cancers that were resected endoscopically by Kudo and colleagues,16 who observed more than 14,000 colorectal lesions. Confirmatory reports have been published.12,17 Epidemiology studies of flat and depressed lesions in Western countries have also shown that depressed lesions have a high likelihood of containing invasive cancer (Table 36.1).18 More than 40% of small (6 to 10 mm) depressed lesions contain submucosal invasive cancer; virtually all large (>2 cm) depressed lesions have submucosal invasion (Table 36.2).16 In comparison, submucosal invasive cancer is rare in flat lesions smaller than 10 mm. The risk increases to about 30% in LST larger than 2 cm. Protruding (polypoid) lesions have the lowest rate—slightly greater than 2%—of submucosally invasive cancer.16

Indications and Contraindications

Indications

Endoscopists most commonly resect polypoid lesions using either a snare loop or a biopsy forceps. The malignant potential of an individual polyp is not fully known, and all polyps except diminutive hyperplastic-appearing polyps in the sigmoid and rectum are removed from otherwise healthy patients. However, the risks of polypectomy must also be considered. Treatment decisions must consider whether substantial risks exist and whether the patient’s overall life expectancy is unlikely to be affected by the generally slow progression of colonic adenomas. The application of principles of statistics whereby the risks considered include the confidence interval must be used at the bedside (see later section). The natural history of progression through the adenoma to carcinoma sequence is estimated to be approximately 10 years,26 so patients with advanced comorbid illnesses and limited life expectancy may not benefit from adenoma resection.

Colonoscopic Mucosal Resection and Submucosal Dissection

Colonic mucosal resection is indicated for resection of nonpolypoid and sessile polypoid adenomas in which resection at the submucosal plane is required to obtain accurate pathology and cure. For lesions suspected to contain high-grade dysplasia or superficial submucosal invasive cancer, mucosal resection is indicated if the lesion can be removed en bloc. Otherwise, submucosal dissection or surgery (after confirmatory biopsy) is indicated. The indications of colonoscopic mucosal resection and submucosal dissection are presented in Box 36.1. Nonpolypoid lesions can be difficult to capture with standard snare and polypectomy techniques. It may be impossible to perform en bloc resection of large flat lesions using standard polypectomy techniques. The application of electrocautery may lead to a burn into the muscularis propria. Resection of large sessile lesions carries similar risks. Mucosal resection technique using submucosal injection can ameliorate these technical difficulties and risks. Depressed lesions, including small ones, are most likely to contain submucosally invasive cancer. Complete removal of small depressed lesions is the only way to determine accurately that invasive carcinoma is not present.

Box 36.1 Indications for Colonoscopic Mucosal Resection and Submucosal Dissection

Because Western pathologists rely primarily on evidence of invasion to diagnose invasive carcinoma (as opposed to cellular and glandular morphology, as is common in Japan), mucosal resection technique is more appropriate to obtain a complete sample of small depressed lesions. The superficial submucosa is typically included in these resection specimens, allowing the pathologist to assess for submucosal invasion. Larger true depressed lesions often are invasive carcinoma. After a confirmatory biopsy and tattooing of the site, these lesions may be best managed with surgery. Mucosal resection is also used increasingly to remove submucosal lesions,27 especially small (<1 cm) rectal carcinoids, where the risk of metastasis is low.28,29

Contraindications

Colonoscopy is usually inappropriate in patients who are pregnant30 or have fulminant colitis, suspected intestinal perforation, fresh intestinal anastomosis, or recent myocardial infarction. Polypectomy and mucosal resection generally should not be performed in patients who have uncorrected bleeding disorders. Although polypectomy and mucosal resection were reported in one study to be relatively safe in lesions smaller than 1 cm, the technique used in that study involved submucosal injection before snaring and clipping to approximate the mucosal defect. Good bowel preparation is crucial for detection of subtle lesions and for resection of particularly large or difficult lesions when an elevated risk of perforation exists. Poor bowel preparation is also a contraindication for performance of complex polypectomy or mucosal resection.

Anticoagulation Therapy

Patients need individualized assessment, balancing the risks of interrupting anticoagulation for colonoscopic polypectomy or mucosal resection against the risks of significant bleeding during and after the procedure.31,32 Patients at very high risk for thrombotic events, such as patients with recent coronary stent placements, should simply defer elective endoscopy until the thrombotic risk is lower. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) has developed guidelines for management of anticoagulation.33,34 Generally, patients at relatively low risk of thromboembolic complications can discontinue warfarin 5 days before the procedure and resume it shortly after standard polypectomy or 7 to 10 days after complex polypectomy or mucosal resection. The international normalized ratio should be 1.4 or less before polypectomy or mucosal resection of a large lesion. High-risk patients, such as patients with atrial fibrillation and concomitant valvular disease, should receive either standard intravenous heparin until approximately 6 hours before the procedure or low-molecular-weight heparin until approximately 24 hours before the procedure. Warfarin generally can be resumed on the night after the procedure with use of intravenous heparin resumed earlier at 2 to 6 hours after the procedure until the international normalized ratio is therapeutic.

Standard heparin has a short half-life compared with low-molecular-weight heparin, so it permits swift immediate reversal of anticoagulation should patients develop postpolypectomy bleeding. In our published experience of colonoscopic resection of small (<1 cm) colorectal lesions in anticoagulated patients, we withheld warfarin for approximately 36 hours only to avoid supratherapeutic anticoagulation resulting from dietary restriction and bowel purge. In this retrospective series, using various polypectomy techniques, including cold snare, standard snare with cautery, and inject and cut mucosectomy, followed by endoscopic clipping, the risk of major delayed bleeding in the resection of 5.1 ± 2.2 mm lesions was 0.8% (95% confidence interval 0.1% to 4.5%).35

Aspirin, Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs, and Antiplatelet Medications

Limited data from the literature suggest that aspirin and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in standard doses do not increase the risk of significant bleeding after colonoscopic polypectomy. ASGE recommends proceeding with standard polypectomy in patients taking these medications.33,34 We are unaware, however, of any recommendations regarding polypectomy or mucosal resection of large or complex lesions. In our practice, patients with significant coronary disease continue to take aspirin, 81 mg/day, after large polypectomy or mucosal resection. The ASGE guidelines for management of platelet aggregation inhibitors, such as ticlopidine and clopidogrel, recommend discontinuation of these agents for 7 to 10 days. Patients receiving combination therapy (e.g., clopidogrel and aspirin) may be at an additional risk of bleeding. Reinstitution of antiplatelet agents should be individualized. Generally, when we believe that the risk of bleeding after endoscopic removal of a large or complex lesion is significant, we recommend that patients refrain from taking other NSAIDs and platelet inhibitors 7 days before the procedure and for 7 to 14 days after it.

Instruments

Snare Loop

Both the endoscopist and the endoscopy assistant must be familiar with the type of snare used. These individuals must understand and have tactile knowledge of the opening and closing of the snare, the closing pressure required to produce optimal coagulation, and the relationship between the size of the tissue being strangulated and the amount of snare being closed. Various snares, each with a slightly different feature, are used for polypectomy and mucosal resection. The choice is made based on personal preference, the size of the lesion, and the technique being used. The minisnare is often used for small polyps, and larger snares are used for larger polyps. Stiffer snares are used for colonoscopic mucosal resection so that flat or depressed lesions can be captured in the snare.27,37

Electrocautery

High-frequency electrical current is employed to facilitate cutting and to coagulate vessels at the resection margin. Colonoscopic resection is typically performed with a monopolar snare. The metallic conducting snare serves as the active electrode, and the circuit is completed via a conducting grounding pad that is affixed to the patient’s skin. In the case of polypectomy, when the snare grasps the polyp, electrical current is applied as the snare is closed to transect the stalk. Electrical current traveling through tissue heats it. The amount of heat transferred to each point in the tissue (per unit time) is given by the product of the square of the current density and the resistance. The current density is the amount of current passing through a unit area. Although the same total current passes through the stalk of the polyp and the grounding pad, the current density is much higher at the stalk because the cross-sectional area is smaller. As a result, the stalk is cauterized while the bowel wall and the rest of the patient’s body generally are left untouched (Fig. 36.4).38

The use of submucosal injection during mucosal resection promotes a better distribution of current because the current can fan out from the resection site to the wide saline cushion. This fan out reduces thermal damage to the larger submucosal vessel and part of the colon wall immediately beneath the lesion.39

Argon Plasma Coagulation

Argon plasma coagulation (APC) is often used after EMR to cauterize the resection margins.40 APC produces electrically conducting argon plasma by guiding argon gas through a delivery catheter that also contains an electrode for delivery of high-frequency current. APC generally creates uniformly deep zones of desiccation, coagulation, and devitalization that measure less than 3 mm deep in total. Because the argon plasma conducts the current, APC can be applied without tissue contact.41–43 In a randomized, controlled study, prophylactic APC to nonbleeding visible vessels at the en bloc polyp (5 to 20 mm) resection sites did not significantly decrease the rate of delayed postpolypectomy bleeding (4.3% in the control group vs. 2.5% in the APC group). The study excluded resections of pedunculated polyps, polyps smaller than 5 mm or larger than 20 mm, polyps that had immediate bleeding, and polyps with no vessels visible at the postresection site.44

Other Instruments

Other instruments that are often used during polypectomy and mucosal resection include the standard sclerotherapy injection needle, endoclip,44,45 endoloop,46–48 Roth net,49 and Tripod. Detailed examples of use of these instruments, which are important for colonoscopic resection, are described subsequently in the Techniques section.

Techniques

Adequate bowel preparation is important; split dosing of bowel preparation is very useful to clean the bowel adequately for the detection and diagnosis of NP-CRN and resection of all types of appropriate lesions. Techniques to prevent looping of the colonoscope during insertion are essential.50 Familiarity with the patient, staff, equipment, and accessories is required. Various techniques are available to perform sophisticated colonoscopic polypectomy, mucosal resection, and submucosal dissection. These techniques, designed to increase the safety of resection, have allowed resections of lesions that in the past would have been accomplished through surgery. Interpretation of the pathology is vital, and preparation of the pathologic specimen requires the participation of the endoscopists at the completion of the procedure.