Chronic constipation is a common problem in the elderly, with a variety of causes, including pelvic floor dysfunction, medication effects, and numerous age-specific conditions. A stepwise diagnostic and therapeutic approach to patients with chronic constipation based on historical and physical examination features is recommended. Prudent use of fiber supplements and laxative agents may be helpful for many patients. Based on their capabilities, patients with pelvic floor dysfunction should be considered for pelvic floor rehabilitation (biofeedback), although efficacy in the elderly is uncertain. Clinical awareness and focused testing to identify the physiologic abnormalities underlying constipation, while being mindful of situations unique to the elderly, facilitate management, and improve patient outcomes.

Definitions and epidemiology

Constipation

Constipation is variably defined, and its diagnosis is often arbitrary. Physicians tend to consider stool frequency (<3 defecations per week), whereas patients more often consider straining, stool consistency, incomplete evacuation, and nonproductive urges to have a bowel movement. A combination of objective (stool frequency, manual maneuvers needed for defecation) and subjective (straining, lumpy or hard stools, incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction) symptoms are used in the Rome III criteria for constipation.

Although most studies suggest an adult prevalence for constipation of about 15%, estimates range from 2% to 27%, with the variability largely explained by the definitions used and population sampled. Like the definitions used, patient perception of constipation is variable, and simply asking patients if they are constipated is unsatisfactory. Most epidemiologic studies demonstrate a higher prevalence of constipation and laxative use in the elderly, particularly in the institutionalized; studies suggest a prevalence for constipation as high as 50%, with up to 74% of nursing home residents using daily laxatives.

In addition to advanced age, risk factors for chronic constipation (CC) include female sex, nonwhite race, physical inactivity, low income and educational level, medications, dietary intake, and depression. Severe constipation is seen almost exclusively in women, with elderly women having rates of constipation two to three times higher than that of their male counterparts. The elderly, who often underestimate their stool frequency, frequently plan their days around their bowel movements, and treatments often precipitate loose stools and incontinence.

Constipation ranks among the top five most common physician diagnoses for gastrointestinal disorders among outpatient clinic visits, and the accompanying use of health care resources is substantial. A recent study identified more than 7 million physician visits per year for constipation in the United States, the majority with primary care providers. However, this probably under-represents the true impact of constipation and subsequent medical use, as many people undoubtedly either do not seek medical attention or use over-the-counter remedies (either alone or in combination with those prescribed by their physician). Patients referred to gastroenterologists tend to represent more chronic or refractory cases.

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

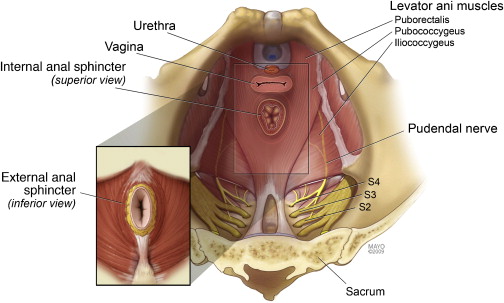

An appreciation of the contribution of the pelvic floor to defecation is essential in understanding constipation. The functional anatomy of the pelvic floor consists of the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani and coccygeus muscles) and anal sphincters, innervated by the sacral nerve roots (S 2–4 ) and pudendal nerve ( Fig. 1 ). Normal functioning of this neuromuscular unit allows the efficient elimination of stool from the rectum. Although the exact prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) in constipation is unknown, studies in tertiary care centers have demonstrated a prevalence of 50% or more. Common in the young, abnormalities of pelvic floor function are frequent in the elderly, especially in older women.

PFD is more common in patients with a history of anorectal surgery or other pelvic floor trauma (including childbirth). In addition to defecatory dysfunction, PFD manifests with disorders of urinary and sexual function. As it relates to constipation, PFD may be more appropriately termed a functional defecation disorder (FDD), which can be characterized by (a) paradoxic contractions or inadequate relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles, or (b) inadequate propulsive forces during attempted defecation.

Pathophysiology

The major causes of constipation include slow colonic transit and PFD. Although the prevalence and clinical significance are unknown, complications of diverticular disease and ischemic colitis may rarely play a role in the elderly. A variety of psychosocial and behavioral issues are also important, and more than 1 mechanism may be present in a single patient. Patients in whom no cause is identified can be categorized as having normal transit constipation.

Aging Process

It is not surprising that the altered mechanical properties (eg, loss of plasticity and compliance), altered macroscopic structural changes (eg, diverticulosis), and altered control of the pelvic floor seen with advancing age impact bowel structure and function. However, although the aging process inevitably generates changes in the colon, the full extent and physiologic impact of those changes on continence and defecatory function remain unclear. In addition, many therapeutic trials exclude older patients, further limiting our appreciation of colonic function and responsiveness in this age group. Indeed, the clinical picture is complicated by more than the aging process itself, as there are a multitude of additional factors ubiquitous amongst many of the aged that impact bowel function (List 1).

List 1: Ten D’s of constipation in the elderly

- •

Drugs (side effects)

- •

Defecatory dysfunction

- •

Degenerative disease

- •

Decreased dietary intake

- •

Dementia

- •

Decreased mobility/activity

- •

Dependence on others for assistance

- •

Decreased privacy

- •

Dehydration

- •

Depression

Enteric Nervous System

The effect of age on the anatomy and function of the enteric nervous system (ENS) is incompletely understood. Although the analysis of changes in the neuronal number in the ENS is not straightforward, studies do suggest an age-related loss of colonic neurons and changes in the morphology of the myenteric plexus of the human colon. A recent study demonstrated the selective age-related loss of neurons that express choline acetyltransferase that was accompanied by sparing of neuronal nitric oxide expressing neurons in the human colon. Theoretically, this could result in a progressive relative increase in inhibitory neurons with advancing age. However, little is known about the regional distribution of neurotransmitters, the impact of aging on the interstitial cells of Cajal, and the influence of the neuronal functional reserve as the colon ages.

The factors that contribute to the presumed alteration in motility during aging are undoubtedly complex, with different effects in different regions of the gut. The eventual effect of these factors on colonic function and defecation is unclear. Overall, gastrointestinal function seems to be well preserved with increasing age, and most healthy elderly individuals have normal bowel function.

Colonic Transit

Investigations differ with regard to the effect of aging on colonic transit; some studies have found a slowing in the elderly, whereas others have detected no significant difference between the elderly and their younger counterparts. Whereas some believe that the normal process of aging reduces the propulsive efficacy of the colon, it is less clear whether this may be related to qualitative or quantitative differences in the colon and ENS, or the numerous causes of secondarily slowed colonic transit that are common amongst the elderly (see Table 1 ). Primary or idiopathic slow colonic transit and global gastrointestinal motility disturbances (intestinal pseudo-obstruction) are uncommon, and few patients have primary colonic inertia or megacolon. Typically, there are straightforward explanations for slow transit, such as the often overlooked but modifiable causes of medication effects and PFD with secondary slowing of colonic transit by inhibitory reflexes.

| Nongastrointestinal Medical Conditions | Medications |

|---|---|

| Endocrine and metabolic disorders | • Analgesics (opiates, tramadol, NSAIDs) |

| • Diabetes mellitus | • Anticholinergic agents |

| • Hypothyroidsim | • Calcium channel blockers |

| • Hyperparathyroidism | • Tricyclic antidepressants |

| • Chronic renal disease | • Anti-parkinsonian drugs (dopaminergic agents) |

| Electrolyte disturbances | • Antacids (calcium and aluminum) |

| • Hypercalcemia | • Calcium supplements |

| • Hypokalemia | • Bile acid binders |

| • Hypermagnesemia | • Iron supplements |

| Neurologic disorders | • Antihistamines |

| • Parkinson disease | • Diuretics (furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide) |

| • Multiple sclerosis | • Iron supplements |

| • Autonomic neuropathy | • Antipsychotics (phenothiazine derivatives) |

| • Spinal cord lesions | • Anticonvulsants |

| • Dementia | |

| Myopathic disorders | |

| • Amyloidosis | |

| • Scleroderma | |

| Other | |

| • Depression | |

| • General disability |

Pelvic Floor Function

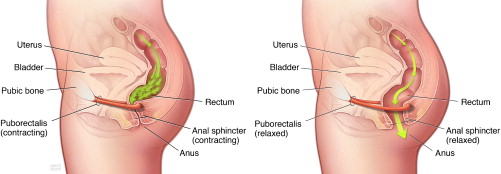

Normal defecation is accomplished through a series of coordinated, neurologically mediated movements of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter ( Fig. 2 ). Abnormalities in this complex series of actions lead to abnormal stool expulsion, or a functional outlet obstruction to defecation. This may be secondary inadequate relaxation or paradoxical contraction of the musculature or the inability to produce the effective propulsive forces needed to expel the stool.

Whereas some studies show no differences in anorectal function between the elderly and their younger counterparts, other physiologic studies have demonstrated various abnormalities with advancing age, including decreased rectal compliance, increased urge thresholds for defecation, and decreased rest and squeeze pressures in the anal canal. PFD is a comprehensive phrase, and other terms relating to defecatory dysfunction include dyssynergia, anismus, obstructed defecation, outlet delay, among others. Although there are subtle differences to the meanings, the key concept of disordered defecation secondary to abnormal pelvic floor function is the same.

In addition to the physiologic types of PFD, specific anatomic abnormalities (rectoceles, sigmoidoceles, rectoanal intussusception, and so forth) may impact defecation. Like the pelvic floor laxity that often accompanies these anatomic findings, they are common in elderly women, but the significance is not always clear. Along with the usual factors associated with aging and constipation, appreciating the pelvic floor and its function is essential for effectual patient management.

Psychosocial and Behavioral Factors

In addition to the personality factors, psychological distress, and a history of physical or sexual abuse that have been associated with constipation, the elderly are at risk secondary to decreased mobility, altered dietary intake, dependency on others, and issues that may develop from social isolation. PFD is a type of behavioral disorder that may be learned at any age in response to specific demands or physical or mental injury. The elderly may ignore calls to defecate, leading to fecal retention. Chronic retention can lead to suppression of rectal sensation, which decreases the desire to defecate. Ultimately, only large stool volumes may be perceived, and, consequently, there is difficulty with rectal evacuation. Defecation disorders interfere with quality of life and may alter interpersonal, intimate, and interfamily relationships.

Pathophysiology

The major causes of constipation include slow colonic transit and PFD. Although the prevalence and clinical significance are unknown, complications of diverticular disease and ischemic colitis may rarely play a role in the elderly. A variety of psychosocial and behavioral issues are also important, and more than 1 mechanism may be present in a single patient. Patients in whom no cause is identified can be categorized as having normal transit constipation.

Aging Process

It is not surprising that the altered mechanical properties (eg, loss of plasticity and compliance), altered macroscopic structural changes (eg, diverticulosis), and altered control of the pelvic floor seen with advancing age impact bowel structure and function. However, although the aging process inevitably generates changes in the colon, the full extent and physiologic impact of those changes on continence and defecatory function remain unclear. In addition, many therapeutic trials exclude older patients, further limiting our appreciation of colonic function and responsiveness in this age group. Indeed, the clinical picture is complicated by more than the aging process itself, as there are a multitude of additional factors ubiquitous amongst many of the aged that impact bowel function (List 1).

List 1: Ten D’s of constipation in the elderly

- •

Drugs (side effects)

- •

Defecatory dysfunction

- •

Degenerative disease

- •

Decreased dietary intake

- •

Dementia

- •

Decreased mobility/activity

- •

Dependence on others for assistance

- •

Decreased privacy

- •

Dehydration

- •

Depression

Enteric Nervous System

The effect of age on the anatomy and function of the enteric nervous system (ENS) is incompletely understood. Although the analysis of changes in the neuronal number in the ENS is not straightforward, studies do suggest an age-related loss of colonic neurons and changes in the morphology of the myenteric plexus of the human colon. A recent study demonstrated the selective age-related loss of neurons that express choline acetyltransferase that was accompanied by sparing of neuronal nitric oxide expressing neurons in the human colon. Theoretically, this could result in a progressive relative increase in inhibitory neurons with advancing age. However, little is known about the regional distribution of neurotransmitters, the impact of aging on the interstitial cells of Cajal, and the influence of the neuronal functional reserve as the colon ages.

The factors that contribute to the presumed alteration in motility during aging are undoubtedly complex, with different effects in different regions of the gut. The eventual effect of these factors on colonic function and defecation is unclear. Overall, gastrointestinal function seems to be well preserved with increasing age, and most healthy elderly individuals have normal bowel function.

Colonic Transit

Investigations differ with regard to the effect of aging on colonic transit; some studies have found a slowing in the elderly, whereas others have detected no significant difference between the elderly and their younger counterparts. Whereas some believe that the normal process of aging reduces the propulsive efficacy of the colon, it is less clear whether this may be related to qualitative or quantitative differences in the colon and ENS, or the numerous causes of secondarily slowed colonic transit that are common amongst the elderly (see Table 1 ). Primary or idiopathic slow colonic transit and global gastrointestinal motility disturbances (intestinal pseudo-obstruction) are uncommon, and few patients have primary colonic inertia or megacolon. Typically, there are straightforward explanations for slow transit, such as the often overlooked but modifiable causes of medication effects and PFD with secondary slowing of colonic transit by inhibitory reflexes.

| Nongastrointestinal Medical Conditions | Medications |

|---|---|

| Endocrine and metabolic disorders | • Analgesics (opiates, tramadol, NSAIDs) |

| • Diabetes mellitus | • Anticholinergic agents |

| • Hypothyroidsim | • Calcium channel blockers |

| • Hyperparathyroidism | • Tricyclic antidepressants |

| • Chronic renal disease | • Anti-parkinsonian drugs (dopaminergic agents) |

| Electrolyte disturbances | • Antacids (calcium and aluminum) |

| • Hypercalcemia | • Calcium supplements |

| • Hypokalemia | • Bile acid binders |

| • Hypermagnesemia | • Iron supplements |

| Neurologic disorders | • Antihistamines |

| • Parkinson disease | • Diuretics (furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide) |

| • Multiple sclerosis | • Iron supplements |

| • Autonomic neuropathy | • Antipsychotics (phenothiazine derivatives) |

| • Spinal cord lesions | • Anticonvulsants |

| • Dementia | |

| Myopathic disorders | |

| • Amyloidosis | |

| • Scleroderma | |

| Other | |

| • Depression | |

| • General disability |

Pelvic Floor Function

Normal defecation is accomplished through a series of coordinated, neurologically mediated movements of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter ( Fig. 2 ). Abnormalities in this complex series of actions lead to abnormal stool expulsion, or a functional outlet obstruction to defecation. This may be secondary inadequate relaxation or paradoxical contraction of the musculature or the inability to produce the effective propulsive forces needed to expel the stool.

Whereas some studies show no differences in anorectal function between the elderly and their younger counterparts, other physiologic studies have demonstrated various abnormalities with advancing age, including decreased rectal compliance, increased urge thresholds for defecation, and decreased rest and squeeze pressures in the anal canal. PFD is a comprehensive phrase, and other terms relating to defecatory dysfunction include dyssynergia, anismus, obstructed defecation, outlet delay, among others. Although there are subtle differences to the meanings, the key concept of disordered defecation secondary to abnormal pelvic floor function is the same.

In addition to the physiologic types of PFD, specific anatomic abnormalities (rectoceles, sigmoidoceles, rectoanal intussusception, and so forth) may impact defecation. Like the pelvic floor laxity that often accompanies these anatomic findings, they are common in elderly women, but the significance is not always clear. Along with the usual factors associated with aging and constipation, appreciating the pelvic floor and its function is essential for effectual patient management.

Psychosocial and Behavioral Factors

In addition to the personality factors, psychological distress, and a history of physical or sexual abuse that have been associated with constipation, the elderly are at risk secondary to decreased mobility, altered dietary intake, dependency on others, and issues that may develop from social isolation. PFD is a type of behavioral disorder that may be learned at any age in response to specific demands or physical or mental injury. The elderly may ignore calls to defecate, leading to fecal retention. Chronic retention can lead to suppression of rectal sensation, which decreases the desire to defecate. Ultimately, only large stool volumes may be perceived, and, consequently, there is difficulty with rectal evacuation. Defecation disorders interfere with quality of life and may alter interpersonal, intimate, and interfamily relationships.

Clinical presentation

As with the definition of constipation, there is variability in patient presentation. Excessive or prolonged straining, assisting stool evacuation by assuming certain positions or with rectal or vaginal digital manipulation, and the sensation of incomplete rectal evacuation are among several features that suggest PFD. Others include urinary and sexual dysfunction, previous pelvic or rectal surgery, history of anal fissures, prolapse, and a history of pelvic floor trauma, including child birthing. Although these symptoms and features may not reliably correlate with formal testing, they are suggestive of PFD, whereas symptoms such as a decreased urge to defecate and infrequent stools may be more suggestive of slow transit. In the elderly, constipation symptoms seem to differ from those observed in younger populations, with the elderly reporting more frequent straining, self-digitation, and feelings of anal blockage.

Fecal seepage is an underappreciated condition that is frequently misdiagnosed as fecal incontinence. Patients often have a history of constipation with the sensation of poor rectal evacuation with frequent, incomplete bowel movements and excessive wiping. They commonly present with anal pruritus and staining of their undergarments. The antidiarrheals often prescribed for presumed incontinence tend to exacerbate the situation. Fecal impaction and overflow incontinence may be associated findings, particularly in the infirmed. Paradoxically, the problem is one of obstructed defecation than true incontinence. A thorough history and examination are essential, especially in those with altered cognitive function.

In addition to fecal seepage and incontinence, fecal impaction can lead to stercoral ulceration and bleeding. CC may be associated with pelvic floor laxity and accompanying rectal prolapse in addition to urinary and sexual dysfunction. Suppression of defecation has been shown to slow gastric emptying and right colon transit, and patients with CC have been shown to have prolonged mouth-to-cecum transit time. It follows that reflex slowing of more proximal gut function can precipitate symptoms. Indeed, constipated patients do have an increase in dyspepsia, abdominal cramping, bloating, flatulence, heartburn, nausea, and vomiting.

Other features to look for include the use of constipating medications, a general decline in physical or mental health, coexisting medical conditions, dietary habits and general psychosocial situation. Chronic pain, which is common in institutionalized patients, often leads to the use of constipating analgesics, which should be assessed. The presence of alarm features, such as rectal bleeding and weight loss, and a family or personal history of colon cancer should be ascertained.

Diagnostic approach

Most patients will present to their primary care physician for the initial evaluation and management of constipation. Rather than focusing on set criteria, it is important to establish the patient’s understanding and characterization of what constipation means to them. Various strategies for the initial diagnosis and treatment of constipation have been employed. Although there is limited data to support their routine use, standard diagnostic studies typically include baseline blood work and structural tests to exclude any significant metabolic or anatomic abnormalities.

Patients with persistent constipation, normal investigations, and a failed response to initial empiric therapies are the ones typically referred to the gastroenterologist. A stepwise, individualized approach to patients with CC is useful. Pursuing relevant studies that help categorize patients as to the cause of their constipation facilitates selection of the appropriate therapy for each specific physiologic subgroup.

History and Physical Examination

A comprehensive history, carefully assessing relevant clinical features, including a thorough medication review, is needed. The physical examination is not complete without a thorough perianal and digital rectal examination, which goes beyond looking for mass lesions, anal strictures, fissures, or stool impaction ( Fig. 3 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree