It has become apparent recently that celiac disease, once believed to be primarily a childhood disease, can affect people of any age. Epidemiologic studies have suggested that a substantial portion of patients are diagnosed after the age of 50. Indeed, in one study, the median age at the diagnosis was just under the age of 50 with one-third of new patients diagnosed being older than 65 years. The purpose of this review is to address the prevalence, clinical features, diagnosis, and consequences of celiac disease in the elderly. The authors also review management strategies for celiac disease and adjust these with emphasis on the particular nutritional and nonnutritional consequences or associations of celiac disease as they pertain to the elderly.

Celiac disease is a chronic autoimmune enteropathy occurring in genetically predisposed individuals following ingestion of wheat gluten and related protein fractions of other grains. In patients with celiac disease, tissue transglutaminase binds to gliadin-derived peptides at the gut level and deamidates certain glutamine residues in these peptides. Antigen-presenting cells that express HLA-DQ2 or -DQ8 then present these gliadin-tissue transglutaminase complexes to the T cells. The process of deamidation increases the affinity of the T cells to the gliadin peptides. These T cells then help the B cells to produce antibodies against the gliadin and tissue transglutaminase antigens through epitope spreading. Such inflammatory response results in mucosal damage in forms of lymphocytic infiltration, crypt hyperplasia, and shortening or loss of the villi, which in turn leads to malabsorption. As a result, patients present with diarrhea, weight loss, steatorrhea, or malnutrition syndromes such as anemia and diminished bone mass due to deficiencies of important nutrients (iron, folate, calcium, and fat-soluble vitamins).

In addition to the morbidities that result from malabsorption, celiac disease is also associated with other autoimmune diseases and malignancies, leading to higher risk of morbidity and mortality among these patients. The risk of autoimmune disorders and cancers particularly increases in older celiac patients and is shown to be associated with the age and the duration of gluten exposure.

Despite growing knowledge regarding celiac disease, little is known about this condition in the elderly. This lack of awareness along with the lower frequency of typical symptoms in older celiac patients compared with the younger ones leads to significant delays in the diagnosis of celiac disease in this population, which in turn increases the morbidity and mortality in this group. This review focuses on the epidemiology, clinical presentations, complications, diagnosis, and management of celiac disease in the elderly population.

Epidemiology

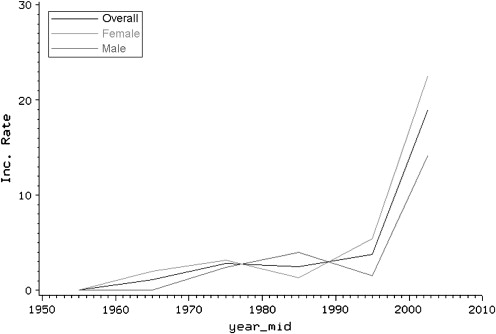

For long time, celiac disease was considered a disease of childhood and was believed to rarely occur in older people. Now there is growing evidence showing an increased rate of diagnosis among adults. Recent reports suggest a trend toward increased incidence of celiac disease, particularly among elderly people. In 1960, only 4% of newly diagnosed celiac disease patients were older than 60 years of age. However, later studies showed that 19% to 34% of new cases of celiac disease are diagnosed in this age group. A survey of 2440 celiac patients in the United States reported that the proportion of celiac disease patients diagnosed in the elderly is similar to that of those diagnosed before 18 years of age (16% vs 15%, respectively). In accord with these studies, a population-based study of Olmsted County residents in Minnesota reported that celiac disease incidence rates (new cases of celiac disease per 100,000 person-years) in people older than 65 years of age increased significantly from 0.0 in 1950 to 1959 to 15.1 in 2000 to 2001. Our recent data suggest that incidence rates are still increasing among all age groups including the elderly ( Fig. 1 , S. Rashtak, MD, unpublished data, 2009).

The estimated prevalence of celiac disease is now about 1% in the general population. In the early 1990s, the prevalence of diagnosed celiac disease in the United States was estimated to be 1 in 5000. Around the same time, reports from Europe showed a 10 to 20 times higher prevalence of celiac disease in Sweden and Italy. Later, a large multicenter study in the United States performed serologic screening for celiac disease and found an overall prevalence of 1 in 133 among patients with no risk; a prevalence that was similar to that of European studies. The prevalence of biopsy-proven celiac disease among adults is reported to be 1.2% and a large population-based study on people between 45 and 76 years of age has shown a seropositive prevalence of 1.2% for undetected celiac disease. More recently, a study from Finland found an even higher prevalence of biopsy-proven celiac disease (2.13%) in older people (52–74 years of age). A recent study has demonstrated that celiac disease may truly occur for the first time in an elderly individual, despite a lifelong apparent tolerance of gluten ingestion, not merely be diagnosed at this age.

Similar to other autoimmune disorders, celiac disease occurs more frequently in women, with a female to male ratio of 2:1. In both men and women the incidence rate of celiac disease continues to increase until 65 years of age, at which point the incidence rate begins to decrease in women whereas it continues to increase gradually in men. Nonetheless, the incidence rate still remains higher in women older than 65 years of age compared with men of the same age.

Clinical presentation

It has become apparent over the last 20 years that celiac disease produces a spectrum of clinical features that extend from severe malabsorption with profound nutritional deficiencies to presentation with a single symptom such as anemia, accelerated osteoporosis, or osteomalacia. For unknown reasons, presentation of intestinal symptoms is less prominent in elderly celiac patients compared with younger ones. Instead, the signs of micronutrient deficiencies may be the first and often the only presentation of the disease in the elderly.

Anemia is present in 60% to 80% of elderly patients with celiac disease and has been mainly attributed to the deficiency of micronutrients, particularly iron. Deficiencies of other nutrients such as folate and vitamin B12 may account for a smaller percentage of anemia in these patients which, in conjunction with iron deficiency, sometimes causes dimorphic peripheral smear. It is hypothesized that anemia of celiac disease is multifactorial, and systemic inflammation may also be a contributing factor in the etiology of anemia in celiac disease. It has been shown that some anemic celiac patients have high levels of ferritin (an acute phase reactant) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, suggestive of systemic inflammation and anemia of chronic disease in these patients.

Although abdominal symptoms are still common in elderly celiac patients, many of these individuals present with milder symptoms such as abdominal bloating, flatulence, and abdominal discomfort, which make the diagnosis more difficult. The classic malabsorptive symptoms such as diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain are less common in elderly celiac patients. It should be noted, though, that celiac disease is the most common cause of steatorrhea in people older than 50 years of age and the second most common cause in those older than 65 years. Nonetheless, it seems that malabsorptive-induced bowel dysfunction is tolerated well among elderly people. Diarrhea, although a common feature, may be mild or intermittent in older celiac patients and a few patients may even present with constipation. In addition, some patients may not present with any intestinal symptoms at all, a condition called silent celiac disease.

Deficiencies of calcium and vitamin D may be another clinical feature of celiac disease leading to decreased bone mass, particularly in elderly patients who are already susceptible to metabolic bone disorders. Malnutrition can also cause hypoalbuminemia in these patients, which additionally may lead to hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia. Hypoalbuminemia itself can also present with edema and ascites in these patients. In about 20% of celiac patients, hepatocellular changes may occur, presenting with an abnormal liver function test, a condition called celiac hepatitis. This condition in turn can lead to further investigation for exclusion of other causes of the liver disease. It has been shown that a gluten-free diet has beneficial effects on resolution of symptoms in celiac hepatitis.

In addition to the gastrointestinal symptoms and malnutrition disorders that result from intestinal involvement, celiac disease may also present through its associated disorders and complications. Dermatitis herpetiformis, well recognized as the skin manifestation of celiac disease, may be the first presentation of gluten sensitivity in celiac patients. Dermatitis herpetiformis occurs in about 25% of patients with celiac disease and is more common in men than women, with a male to female ratio of about 2:1. The average age of presentation is about 40 years, with most patients aged between 20 and 70 years. Nonetheless it can occur at any age, even in childhood. The disease presents with extremely pruritic papulovesicular rash on the extensor surfaces (elbows, knees, buttocks, and scalp). About 80% of dermatitis herpetiformis patients show intestinal alterations consistent with celiac disease in the endoscopic or histopathologic evaluation. However, only 20% of these patients initially have gastrointestinal symptoms of celiac disease. The diagnosis is made by direct immunofluorescence staining of a perilesional skin specimen showing granular IgA deposition in the dermoepidermal junction, more prominently within the papillary tips. The basis of therapy relies on instruction of a gluten-free diet, which controls the underlying pathology and results in slow resolution of symptoms. Dapsone therapy could be used for suppression of initial symptoms and even intermittently for occasional outbreaks.

Other autoimmune diseases are also frequently associated with celiac disease and may provide clues for suspicion of celiac disease in an elderly patient. Autoimmune thyroid disorders are the most common associated autoimmune diseases in elderly celiac patients, with most patients presenting with hypothyroidism. In addition, the risk of intestinal lymphoma and other celiac disease-associated malignancies is higher in elderly people and some patients may present with acute complications of such diseases, including intestinal obstruction or perforation. On occasion celiac disease may present with cavitation of mesenteric lymph nodes and splenic atrophy, or with intestinal ulceration with or without underlying malignancy.

Clinical presentation

It has become apparent over the last 20 years that celiac disease produces a spectrum of clinical features that extend from severe malabsorption with profound nutritional deficiencies to presentation with a single symptom such as anemia, accelerated osteoporosis, or osteomalacia. For unknown reasons, presentation of intestinal symptoms is less prominent in elderly celiac patients compared with younger ones. Instead, the signs of micronutrient deficiencies may be the first and often the only presentation of the disease in the elderly.

Anemia is present in 60% to 80% of elderly patients with celiac disease and has been mainly attributed to the deficiency of micronutrients, particularly iron. Deficiencies of other nutrients such as folate and vitamin B12 may account for a smaller percentage of anemia in these patients which, in conjunction with iron deficiency, sometimes causes dimorphic peripheral smear. It is hypothesized that anemia of celiac disease is multifactorial, and systemic inflammation may also be a contributing factor in the etiology of anemia in celiac disease. It has been shown that some anemic celiac patients have high levels of ferritin (an acute phase reactant) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, suggestive of systemic inflammation and anemia of chronic disease in these patients.

Although abdominal symptoms are still common in elderly celiac patients, many of these individuals present with milder symptoms such as abdominal bloating, flatulence, and abdominal discomfort, which make the diagnosis more difficult. The classic malabsorptive symptoms such as diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain are less common in elderly celiac patients. It should be noted, though, that celiac disease is the most common cause of steatorrhea in people older than 50 years of age and the second most common cause in those older than 65 years. Nonetheless, it seems that malabsorptive-induced bowel dysfunction is tolerated well among elderly people. Diarrhea, although a common feature, may be mild or intermittent in older celiac patients and a few patients may even present with constipation. In addition, some patients may not present with any intestinal symptoms at all, a condition called silent celiac disease.

Deficiencies of calcium and vitamin D may be another clinical feature of celiac disease leading to decreased bone mass, particularly in elderly patients who are already susceptible to metabolic bone disorders. Malnutrition can also cause hypoalbuminemia in these patients, which additionally may lead to hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia. Hypoalbuminemia itself can also present with edema and ascites in these patients. In about 20% of celiac patients, hepatocellular changes may occur, presenting with an abnormal liver function test, a condition called celiac hepatitis. This condition in turn can lead to further investigation for exclusion of other causes of the liver disease. It has been shown that a gluten-free diet has beneficial effects on resolution of symptoms in celiac hepatitis.

In addition to the gastrointestinal symptoms and malnutrition disorders that result from intestinal involvement, celiac disease may also present through its associated disorders and complications. Dermatitis herpetiformis, well recognized as the skin manifestation of celiac disease, may be the first presentation of gluten sensitivity in celiac patients. Dermatitis herpetiformis occurs in about 25% of patients with celiac disease and is more common in men than women, with a male to female ratio of about 2:1. The average age of presentation is about 40 years, with most patients aged between 20 and 70 years. Nonetheless it can occur at any age, even in childhood. The disease presents with extremely pruritic papulovesicular rash on the extensor surfaces (elbows, knees, buttocks, and scalp). About 80% of dermatitis herpetiformis patients show intestinal alterations consistent with celiac disease in the endoscopic or histopathologic evaluation. However, only 20% of these patients initially have gastrointestinal symptoms of celiac disease. The diagnosis is made by direct immunofluorescence staining of a perilesional skin specimen showing granular IgA deposition in the dermoepidermal junction, more prominently within the papillary tips. The basis of therapy relies on instruction of a gluten-free diet, which controls the underlying pathology and results in slow resolution of symptoms. Dapsone therapy could be used for suppression of initial symptoms and even intermittently for occasional outbreaks.

Other autoimmune diseases are also frequently associated with celiac disease and may provide clues for suspicion of celiac disease in an elderly patient. Autoimmune thyroid disorders are the most common associated autoimmune diseases in elderly celiac patients, with most patients presenting with hypothyroidism. In addition, the risk of intestinal lymphoma and other celiac disease-associated malignancies is higher in elderly people and some patients may present with acute complications of such diseases, including intestinal obstruction or perforation. On occasion celiac disease may present with cavitation of mesenteric lymph nodes and splenic atrophy, or with intestinal ulceration with or without underlying malignancy.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of celiac disease in the elderly can be challenging for primary care physicians, which may be in part due to the subtle clinical symptoms, low index of suspicion for celiac disease in elderly people, and distraction toward more threatening conditions such as malignancies. For example, the mild changes in bowel habits may be easily attributed to the functional changes in the intestinal tract due to diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome, mood disorders (anxiety, depression, and so forth), or even be considered as part of the normal aging process. A survey of elderly celiac patients has shown that a substantial number of these patients are incorrectly diagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome many years before their celiac disease is diagnosed, leading to an average delay of 17 years in the diagnosis. In addition, symptoms such as anemia in an elderly celiac patient may lead to extensive evaluation to rule out colon cancer before celiac disease is even considered.

Several diseases are considered in an elderly patient who presents with symptoms of malabsorption. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth, small bowel ischemia, and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (in association with chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer) may be more common in the elderly and sometimes can manifest with chronic malabsorption. These disorders can mimic celiac disease in an older patient or can occur in elderly celiac patients due to their advanced age. Autoimmune enteropathy, albeit an extremely rare condition, has also been described in older patients. Nongranulomatous enterocolitis or self-limited enteritis may be seen in elderly patients too. Malignancies, in particular cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, should be listed as part of the differential diagnosis in an elderly patient presenting with anemia or weight loss.

In general, elderly celiac patients are probably just as likely to have serologic abnormalities as younger patients, and the HLA association with celiac disease persists in this age group. The diagnosis for celiac disease in elderly patients proceeds along the same lines as in younger celiac patients. Serologic tests are frequently used for the diagnosis and follow-up of celiac disease. The basis of serologic testing for celiac disease relies on the measurement of (auto)antibodies, particularly the IgA isotype. The diagnosis is usually confirmed by histologic evaluation of small intestinal biopsy, which is the gold standard test for celiac disease diagnosis. It is important for the primary care physicians to be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of each diagnostic test and select the best option based on each patient’s individual needs.

The current available serologic tests for celiac disease diagnosis include antiendomysial (EMA) and antitissue transglutaminase (TTG) autoantibodies as well as antibodies against gliadin peptides ( Table 1 ). For EMA testing, monkey esophagus or human umbilical cord is used as a substrate. The test is considered highly specific, with a reported specificity of close to 100% in most studies. The sensitivity is also high (>90%) in most reports; however, recent studies have shown that the sensitivity decreases significantly in patients with milder degree of intestinal damage and can reach as low as 30% in patients with partial villous atrophy. The cost of EMA testing is high, which in addition to the subjective and qualitative nature of the test, limits its applicability for routine diagnosis of celiac disease. The TTG IgA test, on the other hand, does not have these limitations of EMA testing, and has a comparable sensitivity (∼90%) and specificity (∼95%) to that of EMA. TTG IgA measurement is therefore recommended as the initial screening test for celiac disease. Antigliadin antibodies that were once used frequently for celiac disease diagnosis are no longer recommended due to their poor sensitivity and specificity. Instead, a newly developed assay that uses deamidated gliadin peptides (DGP) as the antigen has been shown to be significantly more accurate than the conventional gliadin antibody testing for celiac disease diagnosis.

| Test | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| EMA IgA | 85–100 | ∼100 |

| TTG IgA | 80–100 | 90–100 |

| TTG IgG | 20–60 | >95 |

| DGP IgA | 75–95 | >95 |

| DGP IgG | 65–90 | >95 |

| Gliadin IgA | 60–90 | 80–100 |

| Gliadin IgG | 40–80 | 70–90 |

Despite good sensitivity and specificity of these antibody tests, several celiac patients may be missed on the basis of serologic testing alone. Similar to EMA testing, TTG and DGP antibodies have more false-negative results in patients with a milder degree of enteropathy. Another possibility for a false-negative test in a celiac patient is IgA deficiency. In this setting, IgG isotype of relevant antibodies can be used as a diagnostic test. It has been shown that DGP IgG is significantly more sensitive than TTG IgG for celiac disease diagnosis and therefore may be more helpful in these circumstances. The recently developed multiplex immunoassay can simultaneously measure TTG and DGP IgA and IgG antibodies with a similar accuracy to that of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Combination testing may increase the sensitivity and detection of IgA-deficient patients, but still a number of celiac patients, particularly those with partial villous atrophy, remain seronegative for all of the relevant antibodies. It is therefore important that patients undergo intestinal biopsy when there is a high suspicion for celiac disease despite a negative serology. Intestinal biopsy can also confirm the diagnosis in seropositive patients and provide baseline information regarding the degree of intestinal damage for further evaluation of response to the treatment.

The histologic diagnosis of celiac disease is made by the presence of enteropathy in the duodenal biopsy specimens. Increased intraepithelial lymphocyte infiltrate, crypt hyperplasia, and villous atrophy are the three histologic features of celiac enteropathy. There are no age-related changes in the intestine of older individuals and therefore the histologic diagnosis of celiac disease does not differ from that of young patients. Although one might hesitate to subject a very elderly patient with multiple comorbidities to intestinal biopsy as a primary or initial test for celiac disease, older patients are more likely to undergo endoscopy (to exclude other causes of their symptoms) and to have their first diagnosis made by duodenal biopsies rather than serology. It would be important in these patients to provide supportive evidence by means of specific serologic testing and, if negative, compatible HLA genetic susceptibility for celiac disease. Close follow-up of elderly patients is important to ensure appropriate response and the correction of symptoms, and consequences of malabsorption. It should be noted that healing of the intestine may be slow in older patients diagnosed with celiac disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree