Differential

The main histologic finding in clinically acute biliary obstruction is a bile ductular reaction, which may be accompanied by lobular cholestasis but has minimal lobular inflammatory changes. However, a ductular reaction is not specific for acute biliary obstruction and can be seen in many other injury patterns. Of these, the most commonly encountered in clinical practice is a ductular reaction associated with a marked hepatitis or a ductular reaction associated with vascular outflow disease. In most cases, extrahepatic biliary obstructive changes can be separated from these two possibilities by the lack of significant hepatitis or sinusoidal dilatation in the lobules respectively. In the liver transplant population, fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C and antibody-mediated rejection can closely mimic biliary obstruction. In these transplant situations, other histologic findings can help refine the differential, but the final clinical diagnosis requires evaluation of the extrahepatic tree to exclude obstruction.

Special Stains

The edematous changes in acute obstructive disease can be highlighted with an Alcian blue stain, but this is typically not necessary. In most cases, the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) findings are sufficient to generate a diagnosis and differential. However, special stains can sometimes be helpful. The literature in this area is limited and the results somewhat heterogeneous, but there are some general patterns that may be of interest.1 The ductules in cirrhotic livers that have an active ductular reaction tend to stain with CD56, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and CD10 (eFig. 11.1). In cirrhotic livers with little ongoing injury and only mild ductular reactions, the proliferating ductules tend to be negative or only weakly and patchily positive for any of these stains. Bile ductular reactions associated with marked hepatitis show the same immunoprofile as the cirrhotic liver, with positivity for CD56, EMA, and CD10. In contrast, the ductular reaction in acute obstruction tends to be CD56-negative, EMA-positive, and CD10-negative. Bile ductular proliferations with a variety of chronic biliary tract diseases, including primary biliary cirrhosis and biliary atresia,2 tend to be CD56-positive (eFig. 11.2), EMA-negative, and CD10-negative. The ductular reactions in primary sclerosing cholangitis are often heterogeneous, and the immunoprofiles tend to be that of mixed CD56 and EMA positivity with CD10 negative staining. Although these stain patterns can be of interest in specific cases, they should not trump the H&E and clinical findings.

CHRONIC BILIARY OBSTRUCTION

Clinical Findings

Chronic biliary tract obstruction usually presents with cholestasis, including elevated serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels. Chronic biliary tract obstruction can result from many different causes that range from intrahepatic processes, such as stones, tumors, or parasites, to etiologies that cause compression of the extrahepatic biliary tree, such as pancreatic tumors. In most cases, the clinical question at the time of biopsy is not that of acute versus chronic biliary tract disease, but instead, the biopsy is typically performed to establish a diagnosis of biliary tract disease and generate a differential.

Histologic Findings

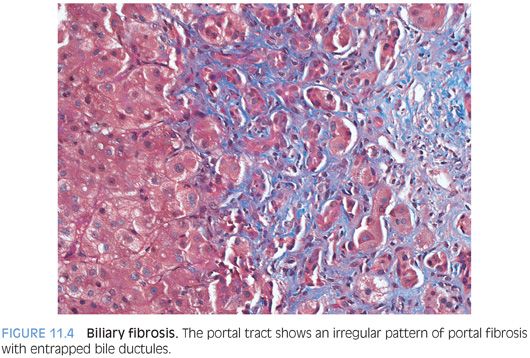

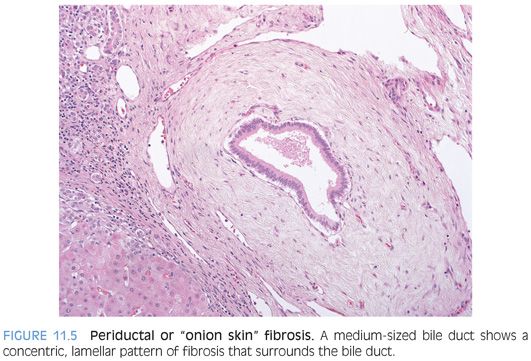

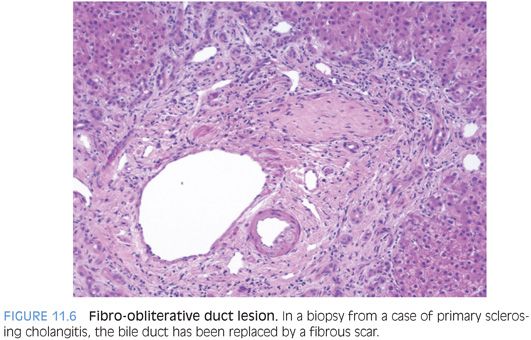

The histologic findings will vary depending on the extent and duration of biliary obstruction. For many biliary tract diseases, the liver changes can be heterogeneous in the early course of the disease, with some but not all portal tracts showing biliary obstructive changes. Early/milder cases will show a patchy bile ductular proliferation with mild mixed portal inflammation, although the inflammation tends to be less than with acute obstruction. The lobules will show cholestasis in some but not all cases. In cases with an active ductular reaction, the trichrome stain can demonstrate a distinctive irregular pattern of portal fibrosis (Fig. 11.4). In time, the ductular reaction will often diminish and the portal tracts may become ductopenic. Several other bile duct changes can suggest chronic obstruction, including bile duct duplication, onion skinning fibrosis (concentric fibrosis around bile ducts), and fibro-obliterative duct lesions (Figs. 11.5 and 11.6). The latter two findings are typically seen only with medium- and large-sized portal tracts, so will not be present in many percutaneous liver biopsies, which tend to sample mostly small-sized portal tracts. Although these lesions are best known for their association with primary sclerosing cholangitis, they indicate generic chronic large duct obstruction and are not etiologically specific.

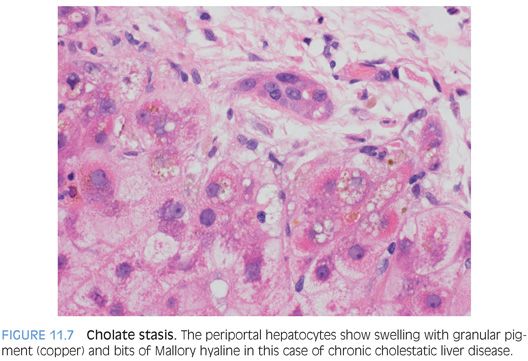

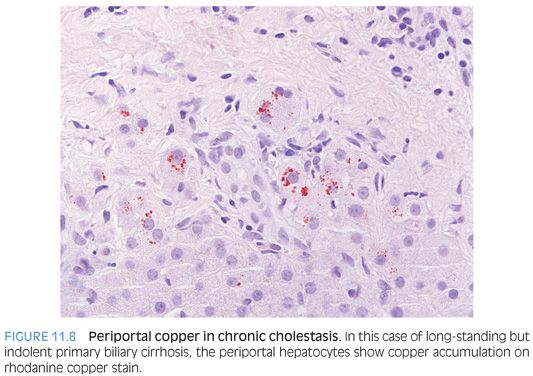

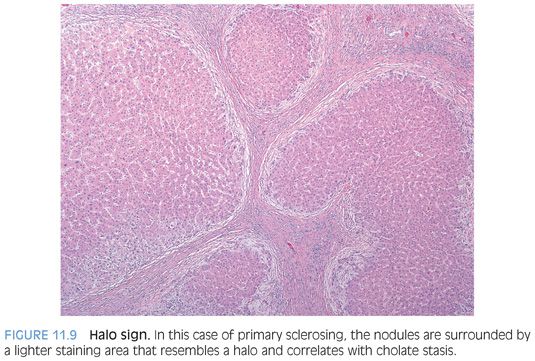

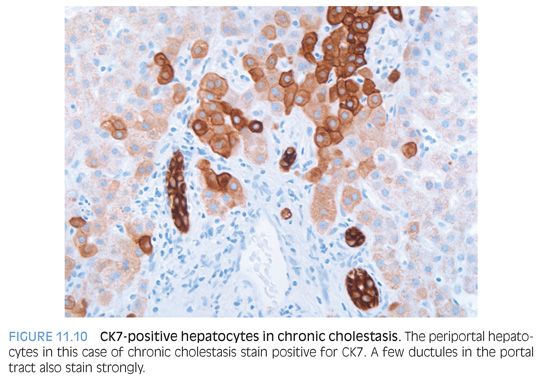

In cases of chronic cholestatic liver disease, the zone 1 hepatocytes can show cholate stasis (Fig. 11.7), with mild hepatocyte swelling, occasional bits of Mallory hyaline, and patchy mild copper accumulation (Fig. 11.8). In cirrhotic livers, the cholate stasis can often be identified at low power by paleness of the periportal hepatocytes, a finding sometimes called the halo sign (Fig. 11.9). A cytokeratin 7 (CK7) immunostain can also highlight zone 1 hepatocytes in cases of chronic cholestatic liver disease (Fig. 11.10).

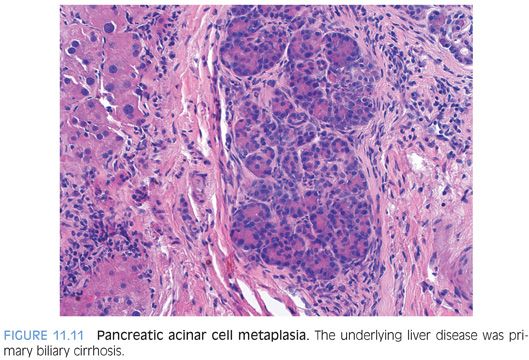

Pancreatic acinar cell metaplasia can be seen in the peribiliary glands surrounding the larger portal tracts in some cases of chronic biliary tract disease. Pancreatic acinar cell metaplasia is more commonly seen in surgical resection specimens than biopsies, because the larger branches of the biliary tree near the hilum are principally affected (Fig. 11.11).

Differential

The differential is influenced by the associated findings in other parts of the liver biopsy. The diagnosis is thus best made in the context of the entire histologic picture. For example, a mild ductular reaction in a liver with significantly active hepatitis is most often reactive to the inflammatory changes and does not typically indicate biliary tract disease. As another example, a mild ductular reaction is common in most cirrhotic livers and does not alone strongly suggest chronic obstructive biliary tract disease. Likewise, ductopenia does not always prove chronic biliary tract disease because it can be seen with a variety of diseases (see Table 4.5). As a final example, cirrhotic livers from any underlying liver disease can decompensate and become deeply cholestatic, a finding that also does not indicate chronic biliary tract disease. These examples illustrate the importance of identifying the predominant pattern of injury and of interpreting all the histologic findings in the context of other changes in the liver biopsy as well as the clinical findings.

Immunohistochemical Stains

Immunostains for CK19 or cytokeratin AE1/AE3 can be very helpful when evaluating for ductopenia. As noted previously, chronic cholestatic livers often show mild copper accumulation and CK7 positivity in the periportal hepatocytes.

PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS

Definition

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is an immune-mediated disease of the bile ducts with patchy inflammation and fibrosis of the biliary tree. The extrahepatic biliary tree is the primary target in most cases, but in a minority of cases, the intrahepatic ducts are the primary targets (small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis). The term primary sclerosing cholangitis should not be confused with autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis, which is a separate entity that has overlapping features of autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis (see Chapter 10).

Clinical Findings

The typical individual with primary sclerosing cholangitis is a young to middle-aged man with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. The inflammatory bowel disease is usually ulcerative colitis but also can be Crohn disease. However, about 20% of individuals with primary sclerosing cholangitis will not have a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. The diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis is established by imaging studies of the extrahepatic biliary tree, which show both strictures and dilatation of the bile ducts, leading to a “beaded” appearance by imaging. About 80% of individuals will also be positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), but this serum test is not specific, and imaging studies are needed to make the diagnosis.

Histologic Findings

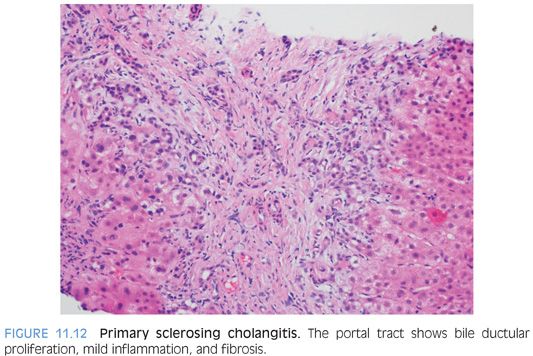

Primary sclerosing cholangitis tends to progress slowly, and individuals can be initially diagnosed at various stages of disease; thus, the histologic findings can vary considerably. In the very early stage of disease, the liver can show minimal nonspecific changes, despite clear evidence of primary sclerosing cholangitis by imaging studies. As the disease progresses, the portal tracts will show patchy bile ductular proliferation with generally mild mixed portal inflammation (Fig. 11.12). The bile ducts proper might show occasional inflammatory cells and reactive changes, but a more diffuse lymphocytic cholangitis suggests other disease processes such as a drug reaction. The lobules generally show minimal inflammatory changes and are not cholestatic. As an exception, primary sclerosing cholangitis presenting in children is often more hepatitic and can have increased lymphocytic infiltrates in both the portal tracts and the lobules.

As the disease progresses, the liver will begin to scar down. The fibrosis begins as a portal-based fibrosis, although the portal fibrosis often has a more irregular outline than seen in chronic viral hepatitis or autoimmune hepatitis. The fibrosis can progress through bridging fibrosis and into cirrhosis. In many cases, the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis is known at the time of the biopsy, and the biopsy is obtained largely to stage the liver fibrosis. Liver biopsies in cases with advanced fibrosis often show ductopenia and will sometimes show onion skinning fibrosis or fibro-obliterative duct lesions. As an important note, onion skinning fibrosis can be easily overdiagnosed, especially when the pathologist knows the patient has ulcerative colitis and is specifically looking for changes of primary sclerosing cholangitis. As a general rule of thumb, onion skinning fibrosis is typically seen in association with other histologic findings of obstructive biliary tract disease and should be interpreted cautiously if it is the only finding on the biopsy.

Fibrosis Staging

Currently, there are no widely used fibrosis staging systems specifically designed for primary sclerosing cholangitis. However, fibrosis can be adequately staged by classifying the biopsy as having no fibrosis, portal fibrosis, bridging fibrosis, or cirrhosis, with the addition of modifiers as needed, for example, “focal early bridging fibrosis” or “extensive bridging fibrosis.”

Differential

Infections of the extrahepatic biliary tree, such as Isospora belli, are rare but can closely mimic primary sclerosing cholangitis on imaging studies, but the diagnosis can be clarified in many cases by biopsy of the extrahepatic biliary tree.3 At the histologic level, the biopsy findings are sufficiently similar between primary and secondary forms of obstructive biliary tract disease that correlation with clinical findings and imaging studies is necessary. Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) sclerosing cholangitis is discussed in a separate section in the following texts. Ischemic cholangitis can also lead to biliary tract disease that closely mimics primary sclerosing cholangitis.4 The vast majority of ischemic cholangitis cases occur in the setting of liver transplantation or after major abdominal surgery with inadvertent injury to the hepatic artery.

SMALL DUCT PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS

Definition

This diagnosis can only be made by liver biopsy. The diagnosis requires the following: (1) liver histologic findings typical of primary sclerosing cholangitis; (2) normal imaging studies of the extrahepatic biliary tree; and (3) exclusion of other causes of chronic biliary tract disease, including infections, drug effect, cystic fibrosis, IgG4 disease, and primary biliary cirrhosis. Most, but not all, individuals will also have chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease.5 Some authors also include individuals whose extrahepatic cholangiogram are nearly normal, with only small minor abnormalities. Intrahepatic cholangiographic abnormalities are seen in many individuals with small duct sclerosing cholangitis.6

Clinical Findings

The clinical findings for individuals with small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis are generally similar to that of large duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. In one study, 88% of individuals with small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis had inflammatory bowel disease, of which 61% had ulcerative colitis.7 The small duct pattern of disease may be somewhat enriched in individuals who have sclerosing cholangitis in the setting of Crohn disease.8 One study suggested individuals with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome have a higher prevalence of small duct sclerosing cholangitis.9

A minority of individuals with small duct sclerosing cholangitis will eventually develop typical large duct primary sclerosing cholangitis,5,10,11 but in most cases, small duct sclerosing cholangitis does not appear to be an “early stage” of classic large duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. Instead, it appears to be a closely related but distinct entity. The overall prognosis is better than that of large duct primary sclerosing cholangitis, with fewer individuals progressing to cirrhosis or cholangiocarcinoma.7,10 Interestingly, many of the individuals who develop cholangiocarcinoma will have first transitioned to large duct primary sclerosing cholangitis.7 Also of note, the small duct sclerosing cholangitis can recur after transplantation.7

Histologic Findings

The histologic findings are essentially the same as for large duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. As is true for all liver diseases, the biopsy findings will vary depending on the length and severity of the injury as well as the fibrosis stage.

IMMUNOGLOBULIN G4 SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS

Definition

IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disease of the biliary tree associated with increased serum IgG4 levels and increased numbers of IgG4-positive plasma cells in the liver inflammatory infiltrates.

Clinical Findings

There is a male predominance, and the mean age is in the mid-60s.12 The average age at first presentation is about 20 years, older than the average age of first presentation for primary sclerosing cholangitis.12 In contrast to primary sclerosing cholangitis, IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis commonly presents with obstructive biliary tract disease (approximately 75%).12,13 Also, in contrast to primary sclerosing cholangitis, IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis is strongly associated with type I autoimmune pancreatitis (more than 90% of cases) but not ulcerative colitis. The cholangiographic findings in IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis are not specific but show variable degrees of intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary strictures.12 The strictures in IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis are steroid-responsive, in contrast to the strictures of primary sclerosing cholangitis, so the proper diagnosis has important clinical consequences. Another important presentation is that of a hilar mass that closely mimics cholangiocarcinoma on imaging studies.

Histologic Findings

The histologic findings in a peripheral liver biopsy from a case of IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis can be very similar to that of primary sclerosing cholangitis. The shared histologic findings reflect the fact that in both cases, much of the histologic changes on liver biopsy are secondary changes that reflect large duct strictures affecting the extrahepatic biliary tree. Both diseases can show mild nonspecific inflammatory changes and a mild ductular reaction on peripheral liver biopsy. However, if larger portal tracts are sampled, the biopsy may show findings that can more strongly suggest IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis. In these cases, the portal tracts can show moderate patchy lymphocytic infiltrates that are enriched for plasma cells and often have scattered eosinophils. The inflammation in some cases is accentuated around the portal veins and can leave a paucicellular “halo” immediately around the bile duct. A bile ductular reaction, with proliferating bile ductules and mild neutrophilic inflammation, can be seen in approximately 50% of cases. Onion skinning fibrosis and duct duplication have been reported,12,13 but ductopenia or a fibro-obliterative duct lesions would be unusual for IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis.

In a subset of biopsies, the portal tracts will be sufficiently inflamed and edematous to form irregular fibroinflammatory nodules that can be seen grossly in resections or wedge biopsies. Histologically, these enlarged, inflamed, and edematous portal tracts can have an irregular or stellate profile. There can be a wide variety of additional changes including lobular cholestasis and a generally mild and patchy lymphocytic lobular hepatitis. Obliterative phlebitis is a rare finding in non–mass-directed biopsy specimens but, when present, favors IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis over primary sclerosing cholangitis. A storiform pattern of portal fibrosis can be seen in some portal tracts, but advanced fibrosis is rare in IgG4 disease.13

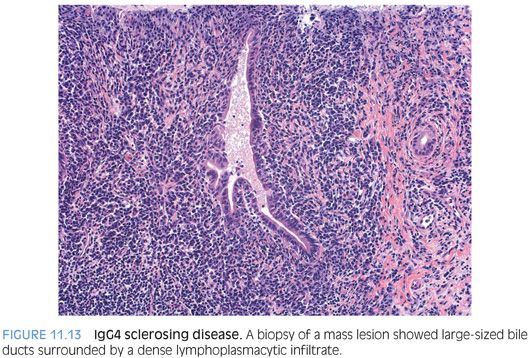

When presenting as a mass lesion, the biopsies show dense fibrosis with chronic inflammation consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 11.13). The fibrosis is often admixed with atrophic cords of hepatocytes and bile ductules. Central vein phlebitis can often be seen. A ductular proliferation is commonly present at the interface with the normal liver. Larger bile ducts, when sampled, show inflammatory and reactive changes.