11 Benign Vaginal Wall Masses and Paraurethral Lesions

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

Infected Skene Glands and Cysts

The differential diagnosis of any anterior vaginal wall mass includes urethrocele, cystocele, urethral diverticulum, ectopic ureterocele, urethral prolapse, malignancy, Skene gland abscess or infection, Skene gland cyst, Bartholin gland cyst or infection, and Gartner duct cyst or infection. Presenting symptoms of Skene gland abscess, infection, or cyst include urethral pain, dysuria, dyspareunia, presence of an asymptomatic mass, recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), urethral drainage, and voiding symptoms. Clues that point to Skene gland involvement are a mass located distally and lateral along the urethra, point tenderness along the lateral and distal aspect of the urethra, and expression of pus. In our practice we consider the diagnosis of Skene gland abscess or infection not only in patients with a palpable anterior vaginal wall lesion but also in patients with chronic urethral pain, recurrent UTIs, or unexplained dyspareunia and an otherwise unremarkable workup. The diagnosis of Skene gland abscess, infection, or cyst can generally be made by history and physical examination. When the diagnosis is in doubt, further workup with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), voiding cystourethrography, transvaginal ultrasonography, or cystourethroscopy may be warranted. A combination of the symptoms described earlier and physical examination findings demonstrating reproducible point tenderness (re-creating the patient’s complaints) distally and laterally along the urethra, palpable cystic mass, or purulent discharge on aggressive milking of the urethra is usually required to diagnose a Skene gland abscess or infection. In the absence of these symptoms or physical findings, imaging results consistent with the diagnosis are required before any treatment is offered.

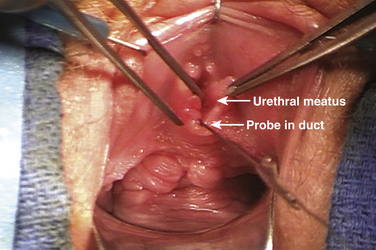

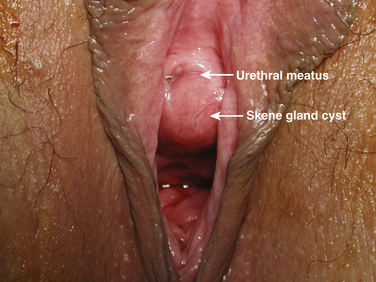

Skene gland infections may present in several ways. In some cases, the duct is visible and may appear inflamed or express a purulent discharge when palpated, but there is no discrete mass (Fig. 11-1). More commonly, there is an associated cystic mass caused by a relative closure of the duct and collection of fluid. These cysts can become quite large and displace the urethral meatus (Fig. 11-2). They may drain spontaneously through the duct or rupture into the anterior vaginal wall.

Figure 11-2 Infected Skene gland cyst displacing the urethral meatus toward the patient’s right side.

Because of the relatively infrequent occurrence of Skene gland abscess or infection, very little information has been published regarding its management. Conservative management may include providing antibiotic therapy or waiting for spontaneous rupture. No guidance is available in the literature regarding the length of time for which conservative management should be tried. We usually treat patients initially with a 2-week course of antibiotics (culture specific if possible). It is felt that the initiation, progression, and propagation of urethral diverticula is secondary to an infection of the periurethral glands. Bacteria associated with a Skene duct abscess include Escherichia coli, other coliform bacteria, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and vaginal flora. If culture results are not available, antibiotic therapy is aimed at covering these common pathogens. If there is no response, then surgical therapy is offered. If a response is seen to antibiotic therapy but symptoms recur, then a repeat course is given. In an era of increasing antibiotic resistance and other complications associated with prolonged antibiotic therapy, it is reasonable to consider surgical intervention after a failure or recurrence of symptoms following one or two courses of antibiotics if the patient is symptomatic and appropriately counseled.

Surgical Technique for Excision of a Skene Gland Lesion

Before excision, cystourethroscopy is performed on all patients in the operative theater. In cases in which there is no obvious mass, every attempt is made to cannulate the opening of the duct with a lacrimal probe or similar tool if possible (see Fig. 11-1). We use two different surgical techniques based on the size of the lesion.

For smaller, noncystic lesions the following technique is used:

1. A small transverse or gently curved inverted-U incision is made just below the urethral meatus.

2. A proximally based vaginal flap is raised.

3. A wedge of distal urethra and periurethral fascia is excised that includes the entire duct and gland.

4. After excision, the urethral mucosa is advanced to the vaginal flaps, with care taken to ensure that there is good apposition of urethral mucosa to vaginal epithelium.

For larger, cystic lesions (see Fig. 11-2) a technique similar to that used for urethral diverticulectomy is performed (see Chapter 10).