TREATMENT. Individuals with AIH are treated by immunosuppression. Steroids, with or without azathioprine, are commonly used, and remission can be achieved in up to 80% of cases. Individuals who do not respond to glucocorticoids and azathioprine may be given other immunosuppressive agents such as mycophenolate, cyclosporin, tacrolimus, or methotrexate. A large proportion of individuals (up to 85%) will relapse when steroids are tapered and require additional therapy.7 The overall clinical course can be influenced by gender, ethnicity, and the amount of fibrosis at presentation.8

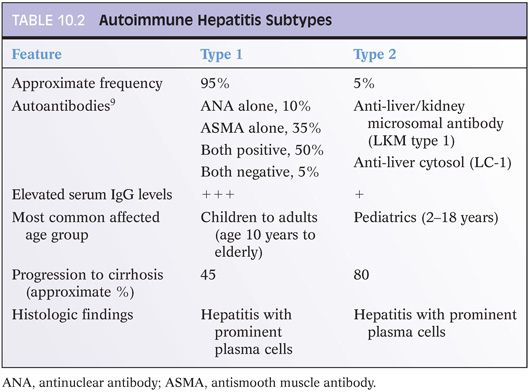

SEROLOGIC FINDINGS AND SUBTYPES

Serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels are typically elevated in AIH. In addition, AIH is associated with elevations in serum autoantibodies that include antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), antismooth muscle antibodies (ASMAs), anti-liver/kidney microsomal (LKM) antibodies, liver cytosol type 1 antibodies (LC-1), and soluble liver antigen (SLA). These autoantibodies are used to define subtypes of AIH (Table 10.2). In the pediatric population, AIH type 1 tends to be more common after puberty, whereas type 2 can be seen in younger children as well. In the pediatric population, antibody titers also tend to be lower than in adults. Overall, the histologic findings do not strongly correlate with the autoantibody patterns, at least not that has been recognized to date, but the subtype of AIH does have clinical and treatment associations (see Table 10.2).

The antigens recognized by the various autoantibodies are defined in many cases.9 Multiple self-antigens appear to be the target for ANA, including double-stranded DNA, chromatin, and ribonucleoprotein. For ASMA, the self-antigens include filamentous actin (F-actin) as well as vimentin and desmin. ASMA directed against F-actin are the most specific for AIH.10 In type 2 AIH, the LKM type 1 (LKM-1) antibodies recognize cytochrome P450 CYP2D6, whereas the LC-1 antibodies recognize formiminotransferase cyclodeaminase. Anti-SLA is now thought to be the same antibody as anti-liver/pancreas (LP) and recognizes selenocysteine synthase. Anti-SLA/LP can be positive in both type 1 and type 2 AIH but also can be the only autoantibody in a subset of patients. Thus, it can be helpful to test for this autoantibody when ANA, ASMA, and LKM-1 antibodies are negative.

When interpreting antibody findings, the overall level of positivity is important. Low-titer antibodies are common in a wide variety of inflammatory conditions and even in the general “healthy” population. Thus, low-titer autoantibodies do not provide strong independent support for a diagnosis of AIH, regardless of what the liver shows. Likewise, high-titer autoantibodies can be found in some individuals who may have very mild liver enzyme elevations but do not have a significant hepatitis on biopsy; in these cases, the high-titer autoantibodies alone are insufficient evidence to make the diagnosis of AIH. As can be seen, a diagnosis of AIH requires both the presence of significant elevations of autoantibodies (variably defined, but the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group suggests a minimum of 1:40 or greater) and an otherwise unexplained hepatitis on biopsy (e.g., viral hepatitis and drug reactions have been excluded). In most cases, the titers will be at least 1:160 or higher. In otherwise healthy children, autoantibodies are rare and low-titer ANA and ASMA, such as 1:20, can also be significant.3 With the newer enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods, positive results are not reported with titers but with a numerical value. These values do not readily translate to titers in most cases, but most individuals with AIH will have values significantly outside the normal range (more than just 1 point or 2). The normal range will vary depending on the assay.

There remains a subset of individuals (approximately 10% of all patients clinically labeled as having AIH) who have an unexplained chronic hepatitis and minimal or no autoantibodies titers that are clinically labeled as presumptive AIH and managed as such. At this point, the tools to further classify this group of patients remains limited, but this group may represent a mixture of disease processes.

ASSOCIATIONS WITH OTHER DISEASES

AIH is associated with a wide range of other autoimmune conditions. On the other hand, many individuals with systemic autoimmune conditions will have elevated serum autoantibodies and minimal or very mild alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevations and will undergo biopsies to rule out AIH. In many of these cases, the biopsies show minimal inflammatory changes with no fibrosis and appear almost normal: Such cases behave different clinically than AIH, and the term autoimmune hepatitis is often best avoided in the pathology interpretation (despite the elevated serum autoantibodies and the minimal inflammatory changes in the liver). An older term sometimes applied to such cases is nonspecific reactive hepatitis.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS

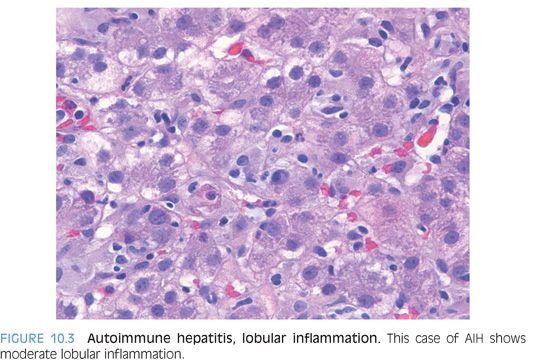

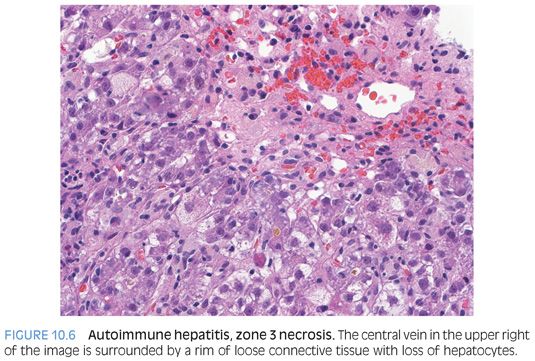

The typical histologic findings in acute AIH include moderate to marked portal inflammation with prominent plasma cells, interface activity, and moderate to marked lobular hepatitis. The lobules will also show scattered acidophil bodies, variable hepatic ballooning, and lobular disarray. The more severe hepatitic cases also commonly have lobular cholestasis and zone 3 necrosis. This typical pattern for AIH is important and helpful to recognize, but remember that (1) there are many variations to this pattern, (2) plasma cell–rich infiltrates can also be seen in both drug reactions and acute viral hepatitis, and (3) interface activity is a reflection of the amount of active inflammation and not a very good indicator of etiology.

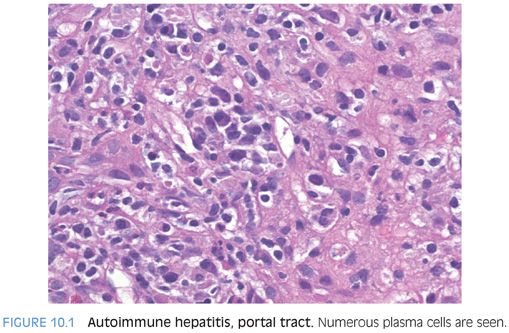

Portal Tracts

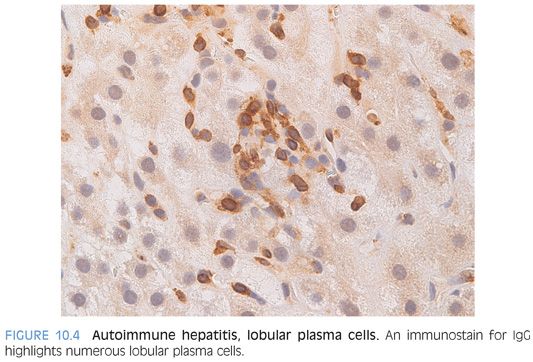

One well-known feature of the infiltrates in AIH is increased plasma cells (Fig. 10.1). The portal tracts show lymphocytic inflammation that is typically moderate to marked, especially at first presentation of an acute hepatitis. The degree of plasma cell prominence will vary considerably, but plasma cells are evident in most cases. The plasma cells can be immunostained and will show predominately IgG-positive plasma cells, paralleling the increased serum Ig levels. About 20% of cases can have few or no plasma cells, so their absence does not preclude a diagnosis of AIH.

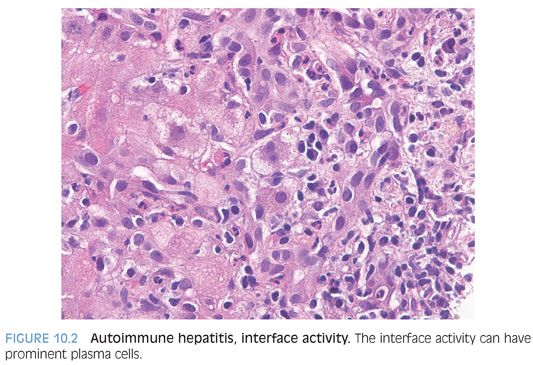

When it comes to identifying AIH on biopsy, interface activity is just as famous as plasma cells as a feature of AIH (Fig. 10.2). Of note, however, interface activity is entirely nonspecific for AIH and is found in many other diseases processes, including drug reactions, acute viral hepatitis, and chronic viral hepatitis. In fact, it is a common component of most scoring systems for chronic viral hepatitis of any etiology. In addition, the sensitivity of interface activity for identifying AIH as a likely etiology—for example, over that of portal or lobular plasma cell–rich inflammation—is also not clear. Instead, interface activity seems to be best understood as a correlate of the degree of inflammatory activity for hepatitis from many different causes.

Lobules

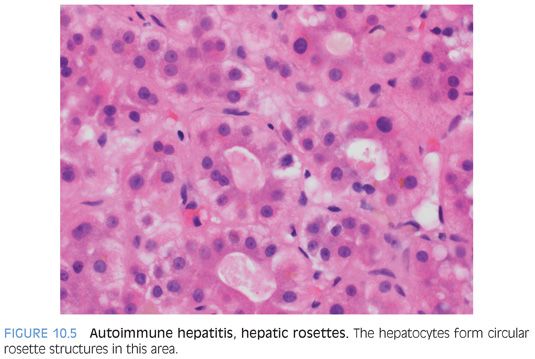

The lobules show varying amounts of lymphocytic inflammation, often with occasional plasma cells (Figs. 10.3 and 10.4). With moderate to marked inflammation, the lobules will often show lobular cholestasis as well as hepatocyte rosettes (Fig. 10.5). In some cases, the lobular inflammation can have a zone 3–predominant pattern (eFig. 10.1). Lobular neutrophils are unusual and suggest a drug reaction or acute viral hepatitis. With marked hepatitis, zone 3 necrosis is also common (Fig. 10.6), and in severe cases, bridging necrosis can be present. Emperipolesis (Fig. 10.7) is another feature identified by some authors as being useful, but in the author’s experience, this finding is difficult to reproducibly identify—that is, emperipolesis is often in the “eye of the beholder,” with some pathologists having an easier time recognizing it than others.