Artificial Bowel Sphincter

Paul-Antoine Lehur

Steven Wexner

Many factors, both anal and extra-anal, contribute to fecal continence. The artificial bowel sphincter (ABS) was designed to restore/create a high-pressure zone in the anal canal in a static manner, without the need for voluntary input to increase pressure.

The ABS corrects the loss of resting anal pressure. It would thus be fallacious to assume that normal continence can be restored by this means, even though the functional results obtained can be highly satisfactory.

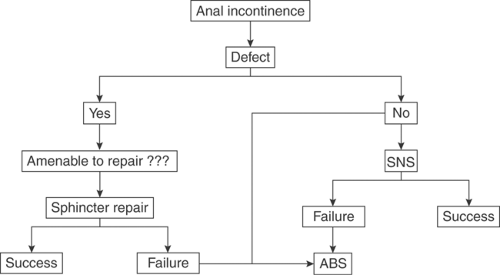

The best indications for the ABS are lesions of the anal sphincters unresponsive to or ineligible for local repair and unresponsive or ineligible for sacral nerve stimulation (SNS). Optimal results are also contingent upon preservation of extra-anal sphincter mechanisms of continence including normal transit time, rectal volume and compliance, and anorectal sensitivity. Thus, the ABS may be recommended, in young subjects, when the chances for successful local (direct) sphincter repair are poor (Fig. 13.1).

In cases of incontinence resulting from sequelae of anal agenesis, there is a lower chance of success. The lack of anal sensitivity and/or a rectal reservoir and the existence of associated colonic motor disorders make all techniques of sphincteric substitution more uncertain. There are no available data to help predict ABS success in this indication, although some patients seem to be better served with techniques of antegrade colonic enemas (Malone procedure).

In cases of neurogenic or neurologic fecal incontinence, it is essential to take into account possible associated dyschezia and excessive perineal descent. The ABS creates an obstacle to rectal evacuation, which can sometimes cause considerable evacuationary difficulties. Continence will not be restored if evacuation is compromised as a result. However, an objective assessment of the state of preoperative transit is not always easy because patients have often modified their diet to avoid incontinence or have had recourse to antidiarrheic treatments. A history of rectal prolapse or treatment for prolapse should be sought before considering implantation of an ABS, insofar as these conditions are indicative of disturbances in the defecation process.

Although the role of the ABS in anoperineal reconstructions after rectal amputation has not yet been fully defined, radiation therapy is probably a relative although not absolute contradiction.

Implantation of an ABS is possible after failure of graciloplasty and in some cases is a planned second stage after a graciloplasty.

Figure 13.1 Present simplified algorithm for management of fecal incontinence related to anal insufficiency. ABS = artificial bowel sphincter; SNS = sacral nerve stimulation.

Likewise, reimplantation of the device can take place immediately after explantation when all or part of the device has to be replaced because of a mechanical failure, or later (6-month interval) in the event of an infection after all inflammatory processes have disappeared.

Globally, the ABS is suitable for well-motivated, selected patients with fecal incontinence

of more than a year’s duration

whose condition is regarded as an important personal, familial, and/or social handicap

as an alternative to definitive colostomy

who are able to manipulate the control pump as required

with sufficient intellectual capacity to understand the functioning of the device and to ensure regular rectal evacuation.

The success of the ABS technique depends on serious consideration of the selection criteria and potential contraindications listed in Table 13.1.

Place of the ABS in the ERA of the Sacral Nerve Stimulation

Recently in a systematic review from Australia (9), the role and place of the ABS was challenged. On the basis of a full review of the literature, the authors concluded that “there was insufficient evidence on the safety and effectiveness of ABS implantation

… and for most patients, the procedure was of uncertain benefit.” Such a statement is clearly not reflective of the practices of either of the authors.

… and for most patients, the procedure was of uncertain benefit.” Such a statement is clearly not reflective of the practices of either of the authors.

Table 13.1 Indications and Contraindications for Artificial Bowel Sphincter | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clearly, SNS has strong and unique advantages as a minimally invasive procedure, and in terms of testing phase, allows a screening process that provides unique patient selection and efficiency. Therefore, both authors have successfully utilized the adaptation of SNS. The SNS procedure however is not a panacea and may not be viable in patients with severe muscle loss. Therefore, there is still a place for a sphincteric replacement, with an ABS in cases of unresponsiveness to or ineligibility for SNS.

Any referral center for the surgical treatment of fecal incontinence must offer a range of options including ABS implantation, SNS, and antegrade irrigation through the colon.

The authors (Paul-Antoine Lehur) experience with both ABS and SNS offered a unique opportunity to compare their respective results. “We compared 15 SNS patients in a case-control study to 15 patients treated with an ABS. Both groups were similar regarding age, gender, incontinence severity, and conservative treatment failure. Preoperative manometric studies were similar in both groups. Results of the study showed that quality of life evaluation was similar in both groups, whereas incontinence and constipation scores were significantly different. As expected, greater improvement in continence is obtained after ABS implantation at the significant price in term of exacerbated obstructed defecation” (6).

Device Description and Functioning

The Acticon Neosphincter ABS Device—Description

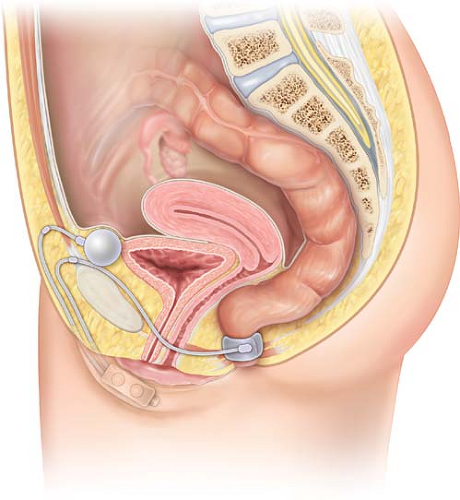

The Acticon Neosphincter ABS (American Medical Systems [AMS], Minnetonka, MN, USA) is a totally implantable device made of solid silicone rubber. It comprises three parts: a perianal occlusive cuff, a control pump with a septum, and a pressure-regulating balloon. These three components are linked together by subcutaneous kink-resistant tubing (Fig. 13.2).

The occlusive cuff is implanted in the upper part of the anal canal, and the closing system incorporated into the cuff uses the initial part of the tubing. The cuff comes in different models with respect to length (9–14 cm) and height (2.0 cm or 2.9 cm).

The choice of the cuff, an important intraoperative consideration, is determined by measurements made during the implantation procedure.

The pressure-regulating balloon, which is implanted in a pocket created in the subperitoneal space, controls the level of pressure applied on the anal canal by cuff closure. Available pressures range from 80–110 cm H2O in 10-cm gradations. Thus, the occlusive effect of the cuff depends on its size (length and height) that determines whether it fits more or less tightly around the anal canal and the pressure level chosen for the balloon.

The control pump is implanted in subcutaneous tissues of the scrotum in men and of the labia majora in women. The hard upper part of the pump contains a resistance regulating the rate of fluid circulation throughout the system and a deactivation button allowing fluid cycling to be stopped by external action. The soft lower part of the pump is squeezed repeatedly to transfer fluid within the device. A septum placed at the bottom of this soft part is intended for postoperative use in case a small amount of liquid needs to be injected. The principle of this septum is similar to that of an implantable portacath.

The Acticon Neosphincter ABS Device—Functioning

The ABS functions semiautomatically:

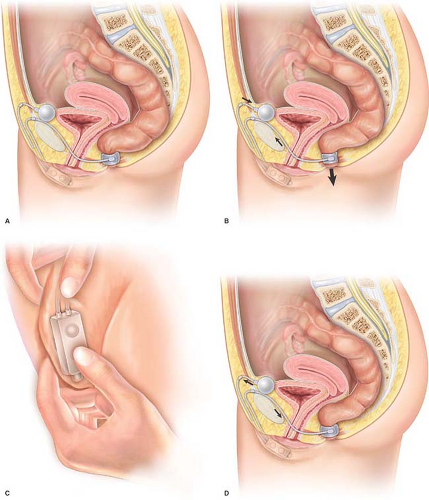

The cuff automatically ensures continuous anal closure at low pressures, close to normal physiological resting pressure. The regulating balloon transmits pressure to the occlusive cuff through the tubing, and the pressure is applied uniformly and nearly circularly to the upper part of the anal canal, restoring a barrier and isolating the rectum from outside.

Defecation is initiated by the patient. Anal opening is achieved by transferring the pressurized fluid from the cuff toward the balloon by means of the control pump. The fluid is transferred by 5–20 squeezes on the pump, each evacuating approximately around 0.5 cc from the cuff, thereby lowering anal pressure and opening the anal canal to expel stool. Suitable compliance allows the volume of the pressure-regulating balloon to transiently increase to receive the several cubic centimeters of fluid contained in the cuff.

Anal closure automatically occurs in 5–8 minutes by passive fluid transfer and a progressive return to baseline pressure in the cuff. The balloon recovers its initial volume during this period, thereby restoring equal pressure throughout the system (Fig. 13.3).

The system can be temporarily deactivated to allow the cuff to be empty and the anal canal to be continuously open. This arrangement can be used during the postoperative period to avoid manipulation of the cuff and pump during the healing period. Deactivation for 6–8 weeks is desirable after implantation to ensure tissue integration of the device. The system can then be activated simply by firmly squeezing the control pump, a procedure not requiring anesthesia performed during an office visit. Deactivation of the cuff in its open position is also necessary for transanal endoscopic procedures in order to avoid any tear or damage to the cuff during the passage of the endoscope. Deactivation during bowel preparation for radiologic or surgical procedures may also be desirable.

Preoperative care includes careful cutaneous and bowel preparation over a 48-hour period.

Skin prep: Two douches of the patient are performed daily with an iodinated solution

Bowel prep: A complete colonic preparation is done, including X-prep and enemas until fluid becomes clear. There is no need for a colostomy, except in the case of

diarrheic patients in whom contamination of the perineal wound may occur from too rapid a resumption of bowel movements.

Antibiotic prophylaxis based on a third-generation cephalosporin and an aminoglycoside is administered in a single dose at the induction of anesthesia.

The author (Steven Wexner) recently performed in a multivariate analysis of 51 ABS implantations (in 47 patients and identified two independent risk factors for early-stage infectious complication after ABS implantation (defined as occurring before ABS activation): an early return of stool passage (before day 2) and an history of perianal infection (17).

This finding reinforces the need for a perfect bowel preparation (what has been called a chemical transient colostomy). Avoiding stool contamination of the perineal wound (or even the operative field at time of operation) is imperative.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree