Fig. 1 a–c

Teenage girl who presented with right lower quadrant pain. a, b Sagittal ultrasound (US) views of right lower quadrant show markedly enlarged right ovary with peripheral follicles and no internal flow, consistent with right ovarian torsion. c Comparison sagittal US view of left lower quadrant shows normal sized left ovary

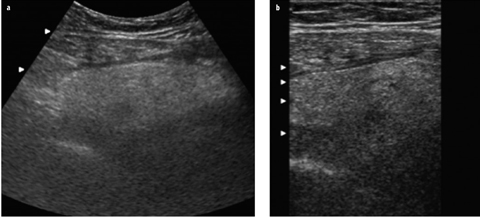

Fig. 2 a, b

Ultrasound (US) images of the right lower quadrant in an 11-year-old girl with right lower quadrant pain show an ill-defined, hyperechoic mass consistent with an omental infarct

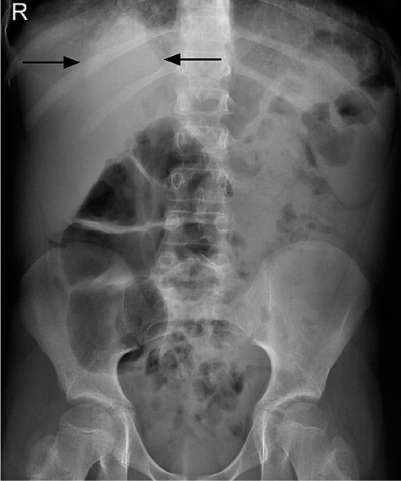

Fig. 3

Young boy who presented with right-sided abdominal pain and fever. The supine abdominal radiograph shows a triangular area of density at the right lung base (arrows), consistent with right lower-lobe pneumonia, the cause of referred pain into the abdomen

Abdominal trauma may also be the cause of an acute abdomen. Occasionally, mild abdominal trauma may cause abdominal pain out of proportion to the degree of trauma, and imaging in these children may reveal an underlying abnormality (such as a neoplasm) or an anomaly (such as ureteropelvic obstruction). Furthermore, one should consider nonaccidental injury or abuse when certain traumatic lesions are found, especially when in combination with presentations such as hematoma of the left lobe of the liver, duodenum, and pancreatitis.

Imaging Modalities

Sonography

Ultrasound (US) plays an ever-increasing role in managing children with acute abdominal pain and has replaced the plain abdominal radiograph as the modality of initial choice in many clinical situations. The major advantages of US are that it does not use ionizing radiation, is relatively inexpensive, and the abdominal viscera, including the bowel, can be well delineated in children. Therefore, many pathological entities can be easily confirmed or excluded on US.

Plain Abdominal Radiograph

Abdominal radiography (AXR) remains a standard method for evaluating the acute abdomen in some clinical situations. It is essential when peritonitis is present and perforation is suspected.

All neonates with an acute abdomen are evaluated with AXR. This modality is essential for evaluating conditions such as necrotizing enterocolitis and congenital bowel obstruction. In the former, the AXR may be diagnostic; in the latter, findings may guide the choice of subsequent (if necessary) contrast examinations of the GI. Radiographic views with a horizontal beam are essential to exclude the presence of free air due to bowel perforation and can be performed with the neonate in the dorsal decubitus (lateral shoot-through view) or left lateral decubitus position.

In older children, the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction can often be made on the supine film alone. A search for air-fluid levels on the upright view does not always add extra information, and a search for free air in the abdomen is often more easily achieved with a lower radiation dose in a single, upright view of the chest, which will also serve to exclude lung pathology.

However, in both the neonate and older child, the AXR findings are often nonspecific, which limits the role of this modality.

Contrast Examinations of the Gastrointestinal Tract

This imaging modality remains important in certain conditions. For example, in congenital low-bowel obstruction, the contrast enema is important in some neonates to establish a diagnosis; in others, it is also useful for therapy (e.g., meconium ileus or meconium plug syndrome). Contrast evaluating the upper GI may also be required to confirm or exclude anomalies of midgut rotation in symptomatic children in whom US is not conclusive (see below).

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) may be reserved for the more complicated imaging situations when US may not provide all necessary information, e.g., appendicitis when gas obscures the right lower quadrant or in older, obese children; and children with abscesses. CT without contrast injection is also extremely helpful in delineating urinary stones when these are not well shown by US.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MR) has a more limited role in children with acute abdominal pain. However, it can depict the anatomy exceptionally well in certain conditions in which it may be used to complement findings on US. These situations include biliary- and pancreaticduct anomalies and gynecological disorders such as complex anomalies associated with hydrocolpos.

Acute Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis is a common clinical entity in pediatrics. In many patients, it is easy to make the diagnosis clinically with certainty, and no imaging is required prior to appendicectomy. However, imaging of the abdomen is now commonly used in children with right lower quadrant pain, even when the clinical diagnosis may be clearcut; however, it is more important in children with nonspecific clinical features.

US is the modality of choice in evaluating children suspected of having acute appendicitis. CT should be reserved for patients in whom US examination is inconclusive or when abscesses are present, in order to better define the extent of the abscesses prior to drainage by the interventional radiology team.

The diagnosis of appendicitis is made on US when the diameter of the appendix is >6 mm and the appendix is noncompressible (Fig. 4). This should not be considered an absolute measurement, and other features should be considered, including edema of the mesentery, hyperemia of the wall of the appendix on color- or power-Doppler examination, presence of an appendicolith, and local fluid collections or abscess formation.

Fig. 4 a–c

An 8-year-old boy with right lower quadrant pain. Ultrasound (US) images show a longitudinal and b transverse views of the enlarged appendix, which measured almost 1 cm in diameter. The surrounding tissue is ill defined and increased in echogenicity due to adjacent edema and inflammation. c The surrounding tissue is also hyperemic. Findings at operation were due to acute appendicitis

Other conditions may cause the appendix to become thick walled and dilated, and these include cystic fibrosis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

Anomalies of Midgut Rotation and Fixation (Malrotation)

The radiologist plays an exceptionally important role in diagnosing this condition, which can potentially lead to bowel necrosis that may require extensive bowel resection and even lead to death. During development, the midgut undergoes a process of growth and lengthening that involves:

Herniation of the midgut into the umbilical cord along the axis of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA)

Rotation of 270° in a counterclockwise direction

Reduction of the midgut into the abdomen by 12 weeks’ gestation

Fixation of parts of the midgut by peritoneum.

The normal process of rotation and fixation is essential for the midgut to assume its normal mature position in the abdomen. However, abnormalities due to the arrest of rotation and/or fixation may occur at any phase of the process and may involve only part or all of the midgut. This may, therefore, lead to a number of variations of malrotation and/or malfixation. The vast majority of these variations are associated with clinical symptoms that usually present within the first few months of life and can be life threatening. Others may be associated with few or no symptoms, and the latter may only be found incidentally.

Malrotation usually leads to obstruction of the duodenum by: (1) peritoneal [Ladd] bands that anchor the cecum to the retroperitoneum across the duodenum in the right upper quadrant; (2) midgut volvulus due to the narrowed base of the mesentery; (3) internal hernia (much less commonly).

The clinical picture and imaging appearances depend upon the nature and degree of obstruction as well as the presence or absence of vascular compromise.

Plain Abdominal Radiograph

In typical cases, there is gaseous distention of the duodenum, but often, appearances may be nonspecific or even normal. One should, therefore, never rely on the plain film findings to rule out malrotation. In some patients, the duodenum may be fluid filled and not visible, and only the stomach is distended with air, simulating a complete or partial gastric outlet obstruction. In children with severe vascular compromise due to volvulus, the entire small bowel may be dilated (with air-fluid levels), resembling a low-bowel obstruction or ileus, but vascular compromise may also produce a gasless abdomen. A volvulus with fluid-filled bowel may also appear as a soft tissue abdominal mass.

Because of the wide variation of appearances on plain radiographs with midgut malrotation, the clinician should never rely on plain radiographs to rule out this entity. Therefore, any child in whom there is a clinical suspicion of malrotation should be examined with modalities that will directly depict the position of the bowel and/or nature of the obstruction. Abdominal US and contrast examination of the upper GI tract are the most valuable modalities in this regard.

Abdominal Sonography

Over the past decade, several sonographic findings have been described in malrotation and include:

Fluid distention of the duodenum

Inversion of the SMA and vein relationship; this can be seen in a small proportion of asymptomatic, normal individuals

Whirlpool sign seen with midgut volvulus

Ascites may rarely be present in neonates with chronic volvulus.

Yousefzadeh drew attention to US depiction of the third part of the duodenum (D3), in the angle between the aorta and SMA, and suggested that documentation of the presence of D3 in this normal position excludes the presence of malrotation. Further data regarding this is required.

Contrast Examinations of the GI Tract

There was much debate about whether the upper GI series or the contrast enema is the most effective imaging modality to diagnose malrotation. Most institutions now rely more heavily upon the upper GI series, but if in doubt, it is prudent to do both. On the upper GI series, the duodenojejunal flexure is absent and the proximal small bowel typically lies in the midline (Fig. 5). Much less commonly, an internal hernia may be delineated (Fig. 6). On contrast enema, the cecum is usually in the right upper quadrant and the ascending colon and hepatic flexure are not correctly positioned. The major difficulty in making or excluding the diagnosis of malrotation is the variation in position that those structures may assume normally or with malrotation. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to describe them all. Meticulous technique is critical to either type of study in order to delineate these structures accurately. The use of too much or too little contrast material may render the study undiagnostic.

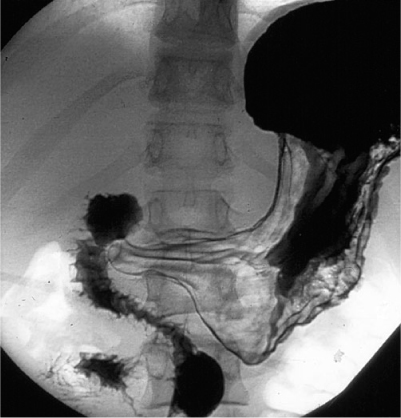

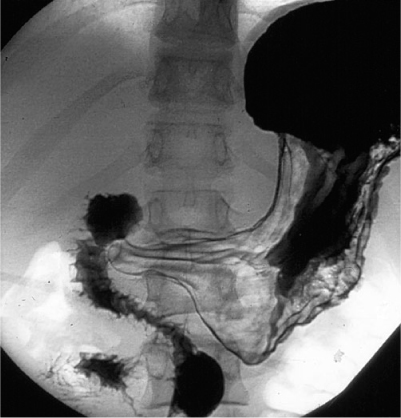

Fig. 5

A 16-year-old boy who presented with acute abdominal pain and bilious vomiting. Upper gastrointestinal series shows a normal stomach and proximal duodenum. However, the third part of the duodenum does not cross the midline normally to the left and, instead, courses inferiorly anterior to the spine and then to the right. Findings are typical of midgut malrotation, which was proven at surgery. There is no evidence of volvulus

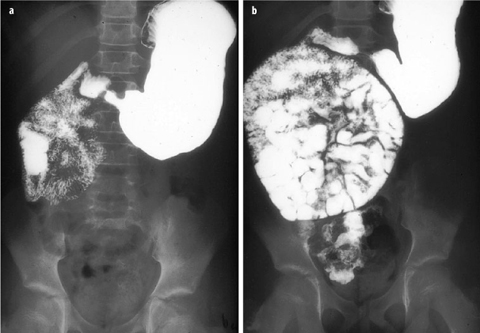

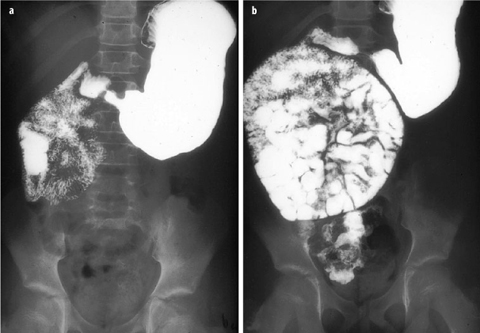

Fig. 6 a, b

Upper gastrointestinal series in a teenage boy who presented with a history of chronic intermittent abdominal pain, occasionally accompanied by vomiting. a Duodenum and proximal small bowel are almost entirely to the right of the spine, consistent with midgut malrotation. b In a delayed image, the small bowel is filled with contrast and has a very rounded and well-defined shape, consistent with a paraduodenal internal hernia proven at surgery

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) usually presents in infants in the neonatal intensive care unit — more commonly in premature neonates. The classic presentation includes abdominal distention and blood in the stool. The radiologist plays an important role at the time of diagnosis of this condition, during follow-up, and in detecting later complications such as strictures.

Abdominal Radiography

At the time of diagnosis, three abnormalities may be present on AXR: bowel dilatation, intramural gas, and portal venous gas (Fig. 7).

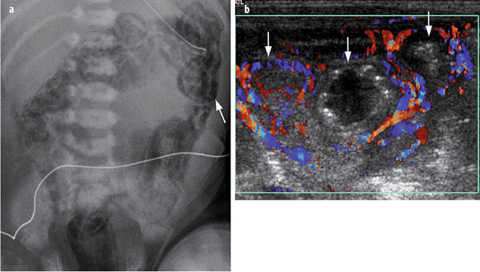

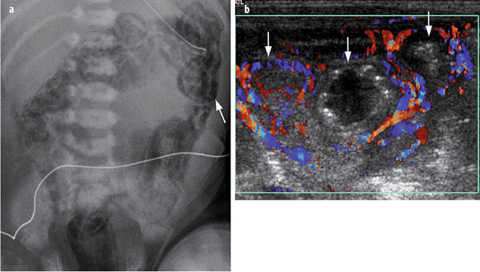

Fig. 7 a, b

a Plain radiograph in a 7-day-old neonate with necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) shows a marked amount of intramural gas throughout the distribution of the large bowel and rectum. Intramural gas is very easily seen in the region of the descending colon (arrow). b Color-Doppler ultrasound (US) image in a 10-day-old neonate with NEC shows three loops of bowel (arrows). The two outer loops are well perfused and indeed are hyperemic, indicating viability. The central loop is distended with fluid and has some hyperechoic foci in the wall, consistent with intramural gas; this loop has no flow and was proven to be necrotic at surgery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree