Gastric and Esophageal Emergencies

Keywords

• Gastric • Esophageal • Emergency • Dysphagia • GERD

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is the sensation of impaired passage of food from the mouth to the stomach that occurs after swallowing. In contrast, globus refers to the constant sensation of a lump or fullness in the throat regardless of swallowing. In individuals older than 50 years the prevalence of dysphagia is estimated to be 16% to 22%.1–3 Dysphagia occurs more commonly in older adults and in patients who have had cerebrovascular accidents, head injuries, esophageal cancers, and neuromuscular disorders. In addition, 60% to 87% of residents of nursing homes experience some form of feeding difficulty, and of those residents with oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration, 12-month mortality is estimated at 45%.1,4–6

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

Causes of oropharyngeal dysphagia include inflammatory, rheumatologic, neuromuscular, and infectious disorders (Table 1). Symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia may include drooling, difficulty in initiating swallowing, need to swallow repetitively to clear food from the mouth and pharynx, coughing, gagging, nasal or oral regurgitation, dysarthria, dysphonia, and aspiration.1,6,7 Chronic oropharyngeal dysphagia may also lead to weight loss, failure to thrive, malnutrition, and recurrent pneumonia.

Table 1 Common causes of oropharyngeal dysphagia

| Structural Lesions | Examples |

| Pharyngeal diverticula | Zenker diverticulum |

| Lateral pharyngeal pouch or diverticula | |

| Intrinsic lesions | Oropharyngeal or laryngeal carcinoma |

| Surgical resection | |

| Cricopharyngeal achalasia | |

| Cricopharyngeal bar and rings | |

| Proximal esophageal webs (Plummer-Vinson) | |

| Radiation injury | |

| Extrinsic compression | Osteophytes, skeletal abnormalities |

| Thyromegaly | |

| Neuromuscular Diseases | Examples |

| Central nervous system | Cerebrovascular accidents, head injury, neoplasm, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington chorea |

| Peripheral nervous system | Poliomyelitis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| Tabes dorsalis | |

| Glossitis, pharyngitis, thrush (sensory) | |

| Neuromuscular transmission myopathies | Myasthenia gravis |

| Polymyositis, dermatomyositis | |

| Muscular dystrophies | |

| Alcoholic myopathy | |

| Thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism | |

| Amyloidosis, Cushing syndrome |

Data from Lind CD. Dysphagia: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2003;32:561.

Esophageal Dysphagia

Esophageal dysphagia results from an obstructive process secondary to either a structural lesion, neuromuscular disorder, or inflammatory process (Table 2). In contrast to oropharyngeal dysphagia, symptoms typically occur 10 to 15 seconds after swallowing, and patients describe a sensation of fullness or pressure located in the substernal or epigastric region. Studies indicate that in approximately 75% of cases patients are able to localize the site of the obstruction based on the location of their symptoms.8 Symptoms associated with esophageal dysphagia may include chest pain, late regurgitation, and odynophagia. Clinical history can be helpful in differentiating between neuromuscular and mechanical causes of esophageal dysphagia. In general, dysphagia that is present equally with solids and liquids suggests a neuromuscular disorder, whereas dysphagia that is present only with solids, or that has progressed from solids to liquids, is more consistent with a mechanical cause. Onset, progression, relief of symptoms, and sensitivity to food temperature also help to distinguish neuromuscular from mechanical causes (Table 3).

Table 2 Common causes of esophageal dysphagia

| Structural Lesions | |

| Intrinsic lesions | Peptic stricture, Schatzki ring |

| Esophageal carcinoma | |

| Leiomyoma, lymphoma | |

| Hiatal hernia | |

| Extrinsic compression | Mediastinal tumors (lung cancer, lymphoma) |

| Vascular structures (dysphagia lusoria) | |

| Surgical changes (fundoplication) | |

| Motor Disorders | |

| Primary motor disorders | Achalasia |

| DES | |

| Hypertensive LES | |

| Nutcracker esophagus | |

| Ineffective esophageal motility | |

| Secondary motor disorders | Collagen vascular diseases or scleroderma, CREST |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Alcoholism | |

| Mucosal Diseases | |

| Esophagitis | GI reflux diseases |

| Infectious esophagitis | |

| Pill induced | |

| Radiation injury | |

| Caustic ingestion | |

Data from Lind CD. Dysphagia: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2003;32:562.

Table 3 Esophageal dysphagia: mechanical versus motor disorders

| History | Mechanical Disorder | Motor Disorder |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Gradual or sudden | Usually gradual |

| Progression | Often | Usually not |

| Type of bolus | Solid (unless high-grade obstruction) | Solids or liquids |

| Response to bolus | Often must be regurgitated | Usually passes with repeated swallowing or drinking liquids |

| Temperature dependent | No | Worse with cold liquids; may improve with warm liquids |

Data from Lind CD. Dysphagia: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2003;32:564.

Neuromuscular Causes of Dysphagia

Achalasia

Achalasia is a primary motility disorder that affects men and women equally, most commonly between the ages of 25 and 60 years. The estimated prevalence in the United States is 10 cases per 100,000.9 The disease results from the degeneration of neurons in the myenteric plexus enervating the esophagus secondary to an inflammatory process. This loss of enervation leads to impaired LES relaxation, decreased esophageal peristalsis, and esophageal dilatation. In addition, there is decreased synthesis of important mediators affecting LES relaxation, nitric oxide, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide.10

The most common presenting symptom of patients with achalasia is a progressive dysphagia to both solids and liquids. Sixty percent of patients also report regurgitation, which typically occurs after meals and can occur nocturnally and lead to cough and aspiration, resulting in significant bronchopulmonary complications in 10% of patients.11 Chest pain is also reported in 20% to 60% of patients. Other symptoms include difficulty belching and heartburn. Weight loss is a rare finding and is generally associated with end-stage disease.

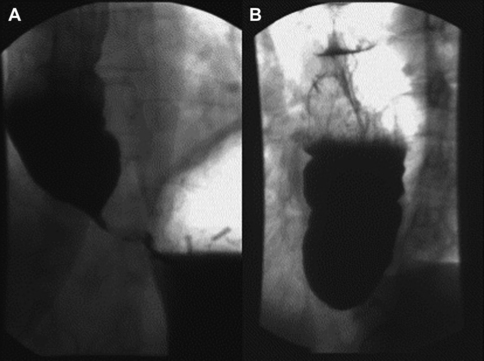

Numerous imaging modalities exist to aid in the evaluation of dysphagia. The barium esophagram is typically the initial study performed. Esophagram findings consistent with achalasia are a tapering of the distal esophagus with contrast in the distal esophageal lumen, classically described as a bird’s beak, as well as dilation of the distal esophagus (Fig. 1). Esophageal manometry has the highest sensitivity for diagnosing achalasia; however, patients presenting with dysphagia typically first undergo upper endoscopy, which may reveal retained food and secretions. However, up to 44% of patients have a normal upper endoscopy.11 Upper endoscopy is especially useful in evaluating for other mechanical causes of dysphagia. Diagnostic findings of esophageal manometry include aperistalsis of the distal esophagus and decreased or absent LES relaxation. Vigorous achalasia is a manometric variant of achalasia in which aperistalsis of the distal esophagus is replaced by normal or high-amplitude esophageal body contractions.12 High-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) combined with contour plot topographic analysis enhances the sensitivity of conventional manometry in the diagnosis of achalasia.12

Treatment of achalasia centers on decreasing basal LES pressure. Medical and surgical treatments exist and include medications, botulinum toxin injection, pneumatic dilatation, and myotomy. Treatment is oriented toward symptom relief and improvement in dysphagia as well as in objective measures of esophageal and LES function. As a result of inefficacy and many side effects, medical therapy with calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine is generally considered a temporizing measure while awaiting definitive management with more invasive therapy. Botulinum toxin injection into the LES decreases basal pressure by targeting acetylcholine-releasing neurons and carries a low side effect profile. Several studies have shown good efficacy and improved symptoms with this treatment, although benefits tend to be short lived and additional injections are required.13,14 Balloon pneumatic dilatation has been used for many years with good success, and numerous long-term outcome studies have shown it to be an effective first-line treatment of achalasia.10,12 The most serious complication from pneumatic dilation is esophageal rupture, which occurs at a mean rate of 2.6%. Laparoscopic myotomy has been shown to have a 90% success rate. However, it can lead to significant GERD and its associated complications. Consequently, myotomy is often performed in conjunction with a GERD-reducing procedure such as fundoplication.

Diffuse esophageal spasm

Like achalasia diffuse esophageal spasm (DES) is a primary motor disorder; however, the true pathophysiology is poorly understood. In general DES is characterized by simultaneous contractions of the distal esophageal smooth muscle, which result in dysphagia and chest pain. Decreased levels of nitric oxide in the myenteric plexus have also been implicated in the pathophysiology. The true prevalence of DES is not known because most of the epidemiologic data are derived from patients referred for a variety of complaints, including noncardiac chest pain and dysphagia. In these patients the prevalence was estimated at 4% to 4.5%.15,16 Furthermore, studies do not reveal a clear relationship between the prevalence of the disease and factors such as age, gender, or race, although data suggest an association with mitral valve prolapse, obesity, and psychiatric illness.17

The diagnosis of DES is made by esophageal manometry criteria and specifically requires synchronous pressure waves (>8 cm/s propagation) with a minimum amplitude of 30 mm Hg.18–20 However, a clear relationship between these manometric criteria and symptoms has not been established. The use of high-resolution manometry may help in diagnosing DES.

Nutcracker esophagus

Nutcracker esophagus is a neuromuscular disorder characterized by high-amplitude peristaltic contractions of prolonged duration that may result in dysphagia and chest pain.21 The diagnosis is frequently made in patients undergoing manometry for evaluation of noncardiac chest pain. Diagnosis is confirmed with manometry when distal esophageal body contractions reach an amplitude of more than 180 mm Hg. Some studies have suggested that changing the diagnostic criteria to require amplitudes as high as more than 260 mm Hg may increase the sensitivity for nutcracker esophagus.22 Much like in DES and other spastic esophageal disorders, manometric findings often do not correlate with symptoms, and the cause of associated pain is unclear. Treatment is similar to that for DES and includes treatment of anxiety and depression.

Mechanical Causes of Dysphagia

Benign esophageal strictures

Benign esophageal strictures form in the setting of chronic inflammation and as a consequence of mucosal and epithelial injury, leading to collagen deposition and fibrous tissue formation.23 Most benign strictures (70%–75%) result from chronic inflammation of the esophageal mucosa by gastric acid from peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and GERD.24 Esophageal strictures may also be caused by Schatzki rings, pill esophagitis, corrosive ingestions, reaction to chronic foreign bodies (nasogastric tubes), sclerotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. Benign strictures are further characterized as simple and complex based on their length, angulation, luminal narrowing, and ability to pass an endoscope.23

Peptic esophageal strictures have a prevalence of 0.1%, and male gender, increased age, and white race are associated with higher rates.25,26 Peptic strictures typically occur in the distal esophagus, where acid reflux is most frequent. Midesophageal to upper esophageal strictures should heighten suspicion of Barrett esophagus and malignancy. Schatzki rings are membranous mucosal rings formed in the distal esophagus at the gastroesophageal junction and represent a variant of peptic stricture disease. Patients often present with dysphagia to solids greater than liquids. Diagnosis can often be made by history alone but is supplemented by barium esophagram and upper endoscopy findings.

Treatment of benign strictures aims both to relieve the obstruction as well as to prevent recurrence. Dilation of the stricture and esophageal lumen is the mainstay of therapy and can be accomplished with balloon dilators, mechanical dilators, and stents, depending on the nature and location of the stricture. Complications include esophageal perforation (0.1%–0.4%),23 bleeding, and bacteremia. Patients often require repeat dilation for recurrence. Treatment of GERD and PUD with antihistamines and PPIs is essential to prevent formation of strictures.

Diverticula

Esophageal diverticula are a rare cause of mechanical dysphagia. The true prevalence of this disease is unknown, but an association with increased age and male gender has been noted.27 Diverticula are characterized by location, wall structure, origin, and mechanism of formation. Most adult diverticula are acquired rather than congenital and have false walls lacking a full muscularis layer. Although midesophageal diverticula occur, most diverticula occur in the distal 10 cm of the esophagus in the epiphrenic region and are formed by pulsion.28 Risk factors for diverticular formation include esophageal dysmotility, obstruction, and focal wall weakness.

Dysphagia associated with diverticula is generally felt to be secondary to the motility disorder and obstruction that led to the diverticula formation rather than to the diverticula itself. Most patients with diverticula are asymptomatic, and the size of the diverticulum does not correlate with the presence of symptoms. If present, symptoms are typically progressive and include dysphagia, regurgitation, vomiting, aspiration, halitosis, chest pain, dyspnea, and dysrhythmias.27 Furthermore, diverticular rupture can lead to significant complications. Diverticula can be diagnosed on chest radiographs but are often discovered on esophagrams and upper endoscopy in patients being evaluated for dysphagia. Endoscopy should be performed to evaluate for associated malignancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree